Introduction

According to a research study conducted by Fazlan et al., (2007), the emergence of interest-free financial institutions has created a new dimension to economic models Widely known as Islamic banks, these interest-free institutions are organized financial intermediaries which operate in accordance with Islamic law (Shariah Law) (Iqbal et al., 2007; M.Kabir H and Mervyn KL, 2007). The term “Islamic Banking” is defined as the conduct of banking operations in consonance with Islamic teachings (Mirakhor, 2000; Haque et al., 2007).

The main principles of Islamic banking activities comprise of prohibition of interest or usury (riba) in all forms of transaction, undertaking business and trade activities on the basis of fair and legitimate profit, giving zakat (alms tax), prohibition of monopoly, and cooperation for the benefit of society and development of all halal aspects of business that are not prohibited by Islam (Haron, 1997; Mirakhor, 2000).

Unlike conventional banking system, the Islamic banking system prohibits usury (riba), the collection and payment of interest, instead, it promotes profit-sharing in all conduct of banking businesses (BNM, 2007).

Over the past four decades, Islamic banking has emerged as one of the fastest growing industry, at an estimated growth rate of 15-20 percent per annum (Haque et al., 2007). It has spread to all corners of globe and received wide acceptance by both Muslims and non-Muslims (Aziz ZA, 2006). Great emphasis is given by the Malaysian government to develop a well functioning and efficient Islamic banking system.

It is not a coincidence that Islamic banking is making its progress in Malaysia but it is the Malaysian government’s vision to develop a progressive and robust Islamic banking industry, rooted in the Islamic core values and principles that best serve the needs of the nation’s economy. It is the aspiration of the Malaysian government to have a strong Islamic banking industry capturing 20 percent of the market share of financing and deposits in the Malaysian financial industry by 2010 (Aziz ZA, 2007).

Background of Islamic Banking in Malaysia

While the opportunities for Islamic banking will continue to grow there is a need to develop products and services that are in line with the changing needs and demands of customers to remain competitive in the business. Generally fiercer level of competition in the banking sector has intensified over the past few years not only in Malaysia but globally.

The process of globalization and liberalization together with digitalization has fueled the intensity of business competition today. Islamic banking in Malaysia, as one of the most important players in the service industry is faced with stiff competition, not only with the long established conventional banking system and the international players but also within themselves.

As competition intensifies and as one of the most important players in the service industry today, Islamic banking is no longer regarded as a business entity striving to fulfill only the religious obligations of the Muslim community, but more significantly as a business that ought to be as competitive as conventional banking.

This necessitates Islamic financial institutions to really understand the needs of their customers towards Islamic banking services. In Malaysia, customers’ positive perception towards Islamic banking is far more crucial mainly due to the fact that Islamic banks have to compete with the dominant and long established conventional banks in a dual-banking system, since 1983 (Asyraf, 2007).

In the context of Malaysia it has been more than two decades now, ever since Islamic banking was launched in Malaysia, way back in 1983, when Bank Islam Malaysia Berhad (BIMB) first commenced its operations (BNM, 2005). And it is the aspiration of the Malaysian government to have a strong Islamic banking industry capturing 20 percent of market share of financing and deposits in the Malaysian financial industry by 2010 (Aziz ZA, 2005).

However, the market share of Islamic assets, deposits and financing as of year 2008, stood at only 15.4 percent, 14.02 percent and 13.96 percent of the industry’s total, despite being in operation for the past twenty five years (BNM, 2008). Undoubtedly, it is a growing market but the growth is slow compared to some countries like Bahrain and Bangladesh which already have exceeded 20 percent of market share in terms of assets, deposits and financing.

Moreover, Bahrain and Bangladesh also practice a dual banking system like Malaysia where, Islamic and conventional banking co-exist, but these countries have successfully captured substantial market share compared to Malaysia. Bahrain which entered into Islamic banking system in 1978 (Bahrain Islamic Bank), has emerged into a leading Global Islamic financial centre in the Middle East within two decades of its existence (BMA, 2007).

Today Bahrain has the highest concentration of Islamic financial institutions than any other country. There are 187 banks operating in Bahrain of which 24 are Islamic banks and it has successfully captured, market share of 32 percent in terms of assets, 29 percent in terms of financing and 37 percent of deposits, respectively (BMA, 2007).

Despite that, in the Asian region, the growth of Islamic banking in Bangladesh which entered into Islamic banking system in 1983 (Islami Bank of Bangladesh), same time with Malaysia, is extremely remarkable (CBA, 2007).

As of 2007, the Islamic banking in Bangladesh has captured market share of 29 percent, 30 percent and 28.5 percent in terms of Islamic assets, financing and deposits respectively (CBA, 2007).

Therefore in the context of Malaysia, although the number of Malaysian banking consumers using Islamic banking products and services are growing, obviously a majority still have not adopted the system. The system has not fully reached or diffused all levels of community like the matured market of conventional banking.

A successful system is one that has been well exposed and at the same time well accepted and extensively used by the people (Aziz, ZA, 2007). In this regard, the ability of the Islamic banking industry to capture a significant market share that is 20 percent by 2010, in a rapidly evolving and competitive financial environment, is a challenge.

Despite that, although Islamic banks have been able to grow quickly, their growth has been constrained by lack of innovation ( Mirakhor, 2000; Asyraf et al., 2007; Bobat, 2007). Whereas, innovation is the key to sustainable and competitive marketing advantage which, will ensure the future growth of Islamic financial markets.

According to Bobat (2007), developing new Islamic financial products in compliance with the Shari’ah is challenging. Therefore, Failure to provide the full range and the right quality of products as per the need of the customers may defeat the very purpose behind Islamic banks’ existence and to stay competitive in the industry.

Thus, developing innovative products and widening the product range calls for substantial and continuous research in this area because understanding customer needs is the key factor that determines the consumer demand and successful marketing of a product or service (Mettawa SA and Almossawi M, 1998; Naser et al., 1999).

Moreover, success in marketing relies on information about complete and up-to-date consumer profiles. Furthermore Islamic banking in Malaysia is still at its developing stage and there are tremendous growth opportunities as it is increasingly gaining prominence in the region and, as it has the potential to be the regional hub of Islamic finance. The growth in market share for Islamic banking assets, financing and deposits (2003-2008) is illustrated in Appendix 1.

Therefore, it is imperative to conduct continuous research and periodical surveys in this area to clearly understand the changing needs and the benefits sought by consumers, which will definitely help the financial institutions to make plausible and effective marketing decisions regarding Islamic banking products.

Unfortunately the marketing aspects of Islamic banking in Malaysia, although important, received little attention from the scholars especially after the year 1999 (Ahmad et al., 2002; Abbas et al., 2003; Asyraf et al., 2007). Furthermore, previous marketing studies in Malaysia are limited in scope and representation, where the main focus was consumers of urban regions and very limited studies were represented by consumers from suburban and rural regions (Abbas et al., 2003; Haque et al., 2007; Asyraf et al., 2007; Fazlan et al., 2007).

Besides that, most of the previous Islamic banking adoption studies in Malaysia were represented by Muslim consumers (Kader et al., 1995; Naser et al., 1999; Ahmad et al., 2002)and only limited studies have included non-Muslims as respondents (Haque et al., 2007; Asyraf et al., 2007).

Malaysia cannot remain unaware of the new competition growing in neighboring Singapore and Thailand. Singapore is an important economy in the South-East Asian region, where new initiatives are aimed, in developing Islamic asset management.

Local financial institutions are warned, that without further growth and consolidation of this industry there is a possibility that Singapore will position itself to eventually become the lead player in South-East Asia (Bobat, 2007).

In this environment, for the Malaysian Islamic financial institutions to formulate and implement successful marketing strategies is a challenge again. This is because the key ingredient here is a clear understanding of the behavior, attitudes and perceptions of their banking consumers (Bobat, 2007).

Research Objectives

The objective of this study is to understand the nature of consumer adoption of Islamic banking, in particular retail banking services, in urban and sub-urban regions of Malaysia. Specifically the objectives are spelled out as below:

- To determine the factors that affect, Islamic banking adoption in Malaysia.

- To compare the similarities and differences of factors that affect Islamic banking services adoption between the urban and sub-urban regions of Malaysia.

- To analyze the perception and preference of banking consumers in regard to Islamic banking services in the urban and suburban regions of Malaysia.

Theory Building

While numerous studies have been undertaken to examine issues in the wider context of Islamic banking system, comprehensive and continuous research in the area of marketing particularly, consumer adoption of Islamic banking services in the specific context of Malaysia has been rather limited.

This study aims to address the question about factors affecting Islamic banking adoption not only in the urban regions of Malaysia but most importantly the sub-urban regions of Malaysia as well. It is crucial to gain a thorough understanding of the differentiated needs and preferences of customers between these two regions, so that appropriate marketing strategies can be formulated to capture the market, instead of having a uniform marketing strategy for all the segments across (Ahmad et al., 2002; Abbas et al., 2003; Asyraf et al., 2007 ).

In addition, the traditional focus of adoption research, always has been on new product innovations and very small but growing number of studies have been conducted on the adoption of financial services (Sathye et al., 1999; Meuter et al., 1999; Black et al., 2001; Gerard, 2003).One exception being Yusof (1999), whose thesis examined the adoption of Islamic banking in Singapore.

Moreover, the marketing aspect of Islamic banking, though important, received little attention from the scholars (Naser et al., 1999; Almossawi, M 2001; Ahmad et al., 2002; Asyraf et al., 2007). This is obvious from the literature review, after the year 1999; there have been very few studies on the marketing aspect of Islamic banking, especially in Malaysia where Islamic banking is still at developing stage.

Apart from the above, in the context of Malaysia, the previous studies related to Islamic banking adoption is limited in scope either due to limited sample size or restrictive in representation (Asyraf et al., 2007).

As opined by Asyraf and Nurdianawati (2007), research by Ahmad and Haron (2002), for instance was represented by only 45 respondents. As for Kader (1993, 1995) and Haron et al, 1994), their samples were restrictive in the sense that they were collected from one single location or district. Kader’s study (1993, 1995), the survey was confined to one location, that is, Kuala Lumpur. Similarly for the studies conducted by Haron et al., (1994), the samples were drawn from three towns namely: Alor Setar, Sungai Petani and Kangar. Whilst, Asyraf and Nurdianawati (2007) in their research have included only the major cities of Malaysia, that is, Kelantan, Penang, Kuala Lumpur and Johore and did not cover any towns from the sub-urban regions and rural regions of Malaysia. These efforts could be inadequate to represent the overall needs and demand of the banking consumers in Malaysia.

Therefore, samples to conduct a comparative analysis for this study will be drawn from the major cities and towns classified as minor settlement regions (suburban) of Malaysia, in order to cover wider scope of representation.

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

Diffusion of Innovation Theory (DOI)

One of the widely used models in the area of innovation adoption is Rogers’ “Diffusion of Innovation” theory (Rogers E.M, 1999, 2003). The scholarly work of Roger (1962) has encouraged research studies in the area of diffusion and adoption extensively (Rogers, 1999, 2003). Approximately 5,200 diffusion studies had been identified by Rogers (2003) while working on the 5th edition of his text. In general, the adoption process has been defined as the process through which individual adopters pass from awareness to full acceptance of a new innovation (Rogers E.M, 1999; 2003). According to Roger there are two levels to adoption. Initially, innovation must be purchased, acquired and adopted by individuals or organizations.

Subsequently, it must be either accepted or rejected by the ultimate users in the society or community. The relative newness of these innovations and the associated uncertainty is what differentiates innovation adoption decisions from other types of decision making (Gerard et al., 2003).

However getting a new idea adopted, even it has obvious advantages, is difficult. Many innovations require a lengthy period of many years, from the time when they become available, to the time when they are widely adopted. Furthermore the same innovation may be desirable for one situation but undesirable for another potential adopter, whose situation differs (Erol et al., 1989; Erol et al., 1990; Gerard et al., 2003).

Rogers (2003) identified five main characteristics of innovations: Relative advantage, compatibility, complexity, observability and trialability as the most important explanation of the rate of innovation adoption (Yusof, 1999; Sohail et al., 2002; Rogers, 2003). Most of the variance in the rate of adoption of innovations, from 49 to 87 percent is explained by these attributes (Rogers, 2003).

Thus, the diffusion literature provides an ideal framework to be applied to the present study which, seeks to extend the research area in a service innovation context, the innovation being Islamic banking. The study would determine which factors according to Rogers’ framework (2003), would fare when applied on a service innovation, more particularly retail banking services which conform to Islamic principles.

Therefore the dependent and independent variable of primary interest to this research is derived from the theory of Diffusion of Innovation model (Rogers, 2003).

Research Variables

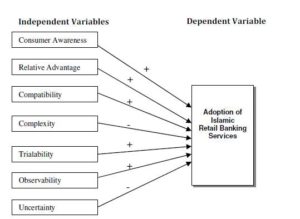

Islamic banking adoption being the dependent variable, the independent variables include: Consumer Awareness, Relative Advantage, Compatibility, Complexity, Trialability, Observability and Uncertainty.

Consumer Awareness

Adoption is the acceptance and continued use of a product, service or idea. According to Rogers (2003), consumers go through a process of knowledge, persuasion, decision and confirmation before they are ready to adopt a product or service. Knowledge occurs when an individual or other decision-making unit is exposed to an innovation’s existence and gains an understanding of how it functions (Rogers, 2003). He has quoted this as the “Pre-contemplation” stage. Consumer awareness have been tested as one of the key variable in numerous studies specifically in the area of on-line banking, internet-banking and self- services technology adoption (Sathye, 1999; Suganthi et al., 1999; Yusof, 1999; Gerad et al., 2003).

However, limited studies have investigated on consumer awareness in the area of Islamic banking adoption. Haron (1994), in his studies stated that about 100 percent of the Muslim population and 75 percent of non-Muslims are aware of the existence of Islamic banking services in Malaysia and out of this only 63 percent understood the difference between Islamic banks and conventional banks. Whereas, some studies reported, Muslim respondents, though aware of fundamental terms in Islam, were almost exclusively unaware of the meaning of specific Islamic financial terms like Mudaraba, Musharaka and Ijara (Gerard, 1997; Kamal et al., 1999).

Proposition 1: There is a positive relationship between customer awareness and the usage of Islamic banking services in Malaysia.

Perceived Relative Advantage

Relative advantage is defined as the degree to which an innovation is perceived as being better than the ‘idea’ it supersedes (Rogers, 1999). Potential adopters want to know the degree to which a new idea is better than an existing one.

According to Yusof (1999), diffusion scholars have found relative advantage to be one of the best predictors of an innovation’s rate of adoption. Rogers (2003) found that adopters invariably perceived relative advantage in terms of the economic benefits and the costs resulting from the adoption of an innovation and improvements that are afforded to their social status.

In addition to these, economic profitability, low initial cost, a decrease in discomfort, social prestige, savings in time and effort and the immediacy of the reward, have been described as the sub-dimensions of relative advantage (Gerard, 2003). Therefore, the present study intend to investigate the economic benefits (profits earnings, service charges and incentives) and service delivery (fast and efficient service, staff competency) of Islamic banking services, within the framework of relative advantage.

Proposition 2: The adoption of Islamic banking by the Malaysian banking consumers is positively related to the perceived relative advantage of using Islamic banking services.

Perceived Compatibility

Compatibility is defined as the degree to which an innovation is perceived as being consistent with existing values, past experiences and the needs of potential adopters (Rogers, 2003). Thus, compatibility is a measure of the values or beliefs of consumers, the ideas they have adopted in the past, and the ability of an innovation to meet their needs (Gerard, 2003). As such, in regards to banking experiences and practices, the Malaysian banking consumers have already possess banking habits from the long operating conventional banks and Islamic banking functions and operations are not new to them. Therefore it is crucial to test the consistency (felt need, previous banking methods) of Islamic banking services as it may have significant impact on the consumers’ willingness to adopt.

Proposition 3: The adoption of Islamic banking services by the Malaysian banking consumers is positively related to the perceived compatibility of using Islamic banking services.

Complexity

Complexity is the degree to which an innovation is perceived as difficult to understand and use (Rogers, 2003).As opined by Yusof (1999) any idea could be classified on the complexity-simplicity continuum. Some innovations are clearly understood by potential adopters whereas others are not. Therefore, complexity has been measured in relation to perceptions about the purpose of the respective innovation, its intended use and the ease with which it can be used (Gerard, 2003).

It is believed that there is a negative relationship between complexity and adoption rate (Rogers, 2003; Gerard, 2003).

Proposition 4: The adoption of Islamic banking by the Malaysian banking consumers is negatively related to the perceived complexity of using Islamic banking services.

Trialability

Trialability is “the degree to which an innovation may be experimented with on a limited basis” (Rogers, 2003). However, customers are unable to try Islamic banking services beforehand in the same way they can test out a hi-fi system or a car before purchasing. Being an intangible, Islamic banking services are, produced and consumed at the same time. However, Islamic financial institutions should respond to this need by allowing potential users to try out their Islamic banking scheme. According to Rogers (2003), an innovation that is trialable can dispel uncertainty about an idea. Thus, for those who are apprehensive about the service, it may give them the necessary confidence to use it (Gerard et al., 2003). It is believed that there is a positive relationship between trialability and adoption rate (Gerard et al., 2003; Rogers, 2003). If an innovation can be designed so as to be tried more easily, it will have a more rapid rate of adoption (Rogers, 2003). As such it is crucial to test the trialability of Islamic banking services as it may have significant impact on the consumers’ willingness to adopt.

Proposition 5: The adoption of Islamic banking by the Malaysian banking consumers is positively related to the perceived trialability of using Islamic banking services.

Observability

Observablity is described as the degree to which the results of an innovation are visible to others (Rogers, 2003). Some ideas are easily observed and communicated to other people, whereas other innovations are difficult to observe or describe to others. According to Yusof (1999) and Gerard (2003) this is especially true for a service where the characteristic of intangibility will hinder its visibility.

Using this argument in the context of Internet banking Gerard (2003), highlighted that observability does not appear to be a contributor to the adoption of Internet banking since it is most unlikely that Internet banking uses are prepared to show the results of their financial dealings to third parties. However Yusof (1999) in his studies, opined that in the case of Islamic banking adoption, it is possible that Muslim consumers would find it easy to explain and provide evaluative feedback to others regarding the benefits of using Islamic banking services, which would further enhance adoption.

Proposition 6: The adoption of Islamic banking by the Malaysian banking consumers is positively related to the perceived observability of using Islamic banking services.

Uncertainty

Uncertainty is the degree to which a number of alternatives are perceived with respect to the occurrence of an event and the relative probabilities of these alternatives (Rogers, 2003). Uncertainty motivates individuals to seek information, as it is an “uncomfortable state of mind”.

According to Roger (2003) a kind of uncertainty is generated by an innovation that is perceived as new by an individual or another unit of adoption. The perceived newness of an innovation, and the uncertainty associated with this newness is a distinctive aspect of innovation decision making process, that is, either to adopt or reject an innovation.

Thus perceived risk, trust and reliability of the system are known to be some of the attributes of uncertainty (Philip.K and Armstrong, 2001; Rogers, 2003). It is believed that there is a negative relationship between uncertainty and adoption rate (Yusof, 1999). The more consumers feel uncertain about an innovation; the lower would be the rate of adoption (Rogers, 2003).

Proposition 7: The adoption of Islamic banking by the Malaysian banking consumers is negatively related to the perceived uncertainty of using Islamic banking services.

Conceptual Model

The Figure 1 below, shows the drived model from propositions. The model offers the conceptual foundation of the research to be conducted. The conceptual model of this research aims to explain, how the perceived attributes of innovation determines the adoption of Islamic banking, in particular, retail banking services in Malaysia. In addition it also aims to explain how the relationship of the independent and dependent variables are modified or rather altered by the moderating factors.

Figure 1: Conceptual Model of Islamic Retail Banking Services Adoption

CONCLUSION

This concept paper provides a theoretical discussion on Islamic Banking development in the past and the present. Based on the extensive literature review in the areas of Banking and Islamic Banking, together with the evaluation of the suitability of applying Theory of Diffusion of Innovation Model, this study proposes a conceptual framework, for the study of adoption of Islamic Retail Banking services by Malaysian consumers.

The study further recommends that the conceptual model with independent and dependent variables tested for relationships and to confirm the model fit upon collection of the research data. As such, the model also comprises prepositions.

REFERENCES

Abbas, S.Z.M., Hamid, M.A.A., Joher, H., Ismail, S. (2003) ‘Factors That Determine Consumers’ Choice in Selecting Islamic Financing Products’, paper presented at the International Islamic Banking Conference, 9-10th September, Prato.

Ahasanul Haque, Jamil.O and Ahmad .Z (2007) ‘Islamic Banking: Customer perception and its prospect on bank product selection towards Malaysian customer perspectives’, paper presented at the Fifth International Islamic Finance Conference, 3-4th September, Kuala Lumpur.

Ahmad, N, and Haron, S (2002) ‘Perceptions of Malaysian corporate customers towards Islamic banking products and services’, International Journal of Islamic Financial Services, 3:1, 13-29.

Almossawi, M (2001) ‘Bank selection criteria employed by college students in Bahrain: an empirical analysis’, International Journal of Bank Marketing, 19:3, 115-25.

Asyraf, W, D and Nurdianawati, A (2007) ‘Why do Malaysian Customers patronize Islamic Banks’, International Journal of Bank Marketing, 25:3, 142-160.

Aziz, ZA (2005) Building a progressive Islamic Banking sector: Charting the Way Forward, 10-Year Master Plan for Islamic Financial Services Industry, Bank Negara Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur.

Aziz, ZA (2006) Islamic Banking and Finance Progress and Prospects, Collected Speeches 2000-2006, Bank Negara Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur.

Aziz, ZA (2007) Governor of Central Bank of Malaysia: Keynote address at INCEIF, Inaugural Intellectual Discourse, 23 February, Kuala Lumpur.

Bahrain (2007) Annual Report, Bahrain Monetary Agency, Bahrain.

Black, N.J., Lockett, A, Winkhofer, H. and Ennew, C (2001) ‘The adoption of internet financial services: a qualitative study’, International Journal of Retail and Distribution Management, 29:8, 390-8.

Bangladesh (2007), Annual Report, Central Bank of Bangladesh, Dhaka.

Bangladesh (2008), Annual Report, Central Bank of Bangladesh, Dhaka.

Elvan, T and Dough, T (2004) Understanding Marketing Research, Pearson Education Publications Ltd, Australia.

Erol, C and El-Bdour, R (1989) ‘Attitude, behavior and patronage factors of bank customers towards Islamic banks’, International Journal of Bank Marketing, 7:6, 31-7.

Erol, C, Kaynak, E and El-Bdour, R (1990) ‘Conventional and Islamic bank patronage behavior of Jordanian customers’, International Journal of Bank Marketing, 8:5, 25-35.

Fazlan, S and Mohammad, A (2007) ‘The efficiency of Islamic Banks: Empirical Evidence from the MENA and Asian Countries Islamic Banking Sectors’, paper presented at the Fifth International Islamic Finance Conference, 3-4th September, Kuala Lumpur.

Haron, S, Ahmad, N and Planisek, SL (1994) ‘Bank patronage factors of Muslim and non-Muslim customers’, International Journal of Bank Marketing, 12:1, 32-40.

Haron S (1995) ‘The Framework and Concept of Islamic Interest-Free Banking’, Journal of Asian Business, 5:2, 27-36.

Haron S (1997) Islamic Banking Rules and Regulations, Pelanduk Publications (M) Sdn Bhd, Kuala Lumpur.

Iqbal, Z and Mirakhor, A (2007) An Introduction to Islamic Finance: Theory and Practice, John Wiley and Sons Ltd, Chichester.

Kader, RA (1993), ‘Performance and market implications of Islamic banking: a case study of Bank Islam Malaysia Berhad’, Unpublished PhD Thesis, Durham University, Durham.

Kader, RA (1995), Leading Issues in Islamic Banking and Finance, Pelanduk Publications (M) Sdn Bhd, Kuala Lumpur.

Kamal Naser, Ahmat Jamal, Khalid-Al Khatib (1999) ‘Islamic Banking: A Study of Customer Satisfaction and Preferences in Jordan’, International Journal of Bank Marketing, 17:13, 135-150

Malaysia (2005), Annual Report, Bank Negara Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur.

Malaysia (2006), Annual Report, Bank Negara Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur.

Malaysia (2007), Annual Report, Bank Negara Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur.

Malaysia (2008), Annual Report, Bank Negara Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur.

Matthew Lane Meuter (1999), ‘Consumer Adoption of Innovative Self-Service Technologies: A multi-method investigation’, PhD Thesis, Arizona State University, USA.

M. Kabir H. and Mervyn K. Lewis (2007), Handbook of Islamic Banking, Edward Elgar Publishing Limited, UK.

Metawa, SA and Almossawi, M (1998), ‘Banking behavior of Islamic bank customers: perspectives and implications’, International Journal of Bank Marketing, 16:7, 299-313.

Mirakhor, A (2000) ‘General Characteristics of an Islamic Economic System’, Anthology of Islamic Banking, Institute of Islamic Banking and Insurance, London, p.11-31.

Naser, K, Jamal, A and Al-Khatib, L (1999) ‘Islamic banking: a study of customer satisfaction and preferences in Jordan’, International Journal of Bank Marketing, 17:3, 135-50.

Norazah M, Suki (2006) ‘Consumer Innovation and Adoption of On-line Shopping: Malaysian Internet User’s Prospective’, PhD Thesis, Multimedia University, Malaysia.

Philip Gerard and Cunningham, JB (1997) ‘Islamic banking: A study in Singapore, International Journal of Bank Marketing, 15:6, 204-16.

Philip Gerard and Cunningham, JB (2003) ‘The diffusion of Internet Banking among Singapore Consumers’, International Journal of Bank Marketing, 21:1, 16-28.

Philip Kotler and Gary Armstrong (2001) Principles of Marketing (9th edn), Prentice Hall Publication Inc, New Jersey

Rogers EM (2003), Diffusion of Innovations (5th edn), The Free Press, New York.

Rogers EM (1999), Diffusion of Innovation (4th edn), The Free Press, New York.

Sadiq Sohail, M and B.Shanmugham (2002) ‘E-banking and customer preferences in Malaysia: an Empirical investigation’, International Journal of Information Sciences (Elsevier), 15:2, 207-217.

Sathye, M (1999) ‘Adoption of Internet banking by Australian consumers: an empirical investigation’, International Journal of Bank Marketing, 17:7, 324-334.

Suganthi, Balachandher and Balachandran (2001) ‘Internet Banking Patronage: An Empirical Investigation of Malaysia’, Journal of Internet Banking and Commerce, 6:1, 15-21.

Yakub Bobat (2007) ‘Islamic Banking: Need for Innovation’, paper presented at the Fifth International Islamic Finance Conference, 3-4th September, Kuala Lumpur.

Yusof MYR (1999) ‘Islamic Banking: Adoption of a Service Innovation’, unpublished MSc. thesis, NTU, Singapore.