Research Methodology

This section of the research determines the methodology employed. To conduct this research, quantitative method was used and the data collected through a questionnaire survey. The survey instrument was a questionnaire.

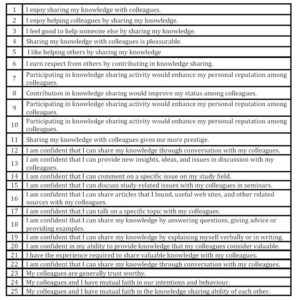

Items used in the research model were deemed relevant and adapted from prior studies in the field of knowledge sharing (Lee, 2001; Bock, Zmud, & Kim, 2005; Lin, 2007; Kankanhalli et al., 2005; Wasko & Faraj, 2005; Hsu et al., 2007; Kuo & Young,2008; Lin,2006; Lee & Choi,2003; Estephan, 2005; Rowden, 2009; Kilroy, 2009; Worthington et al., 2003).

However, it was modified to suit the present study (see Appendix 1). Before distributing the final questionnaire, a pilot survey was carried out among 200 respondents conveniently selected from the target population to examine its validity and reliability and only 160 were used with no missing data. Based on the information collected from these respondents, the final questionnaire was developed with slight modification. SPSS 20.0 software was used to analyse the data collected. The cronbach alpha values for the entire constructs used in the questionnaire were above 0.80 which is considered reliable according to Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson, Tatham (2006).

The questionnaires were distributed to postgraduate students in six public Malaysian universities in Klang Vally, where most of the public universities located.

The questionnaire was self-administrated and distributed personally by hand to the respondents inside their classes after obtaining permission from their lecturers in order to have a higher response rate. A total of 1683 questionnaires were distributed to the respondents. Only 1267 questionnaires were used for further analysis.

Data Analysis and Result

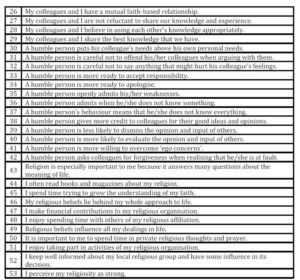

This section presents the analysis of the demographic characteristics of the respondents. This is followed by the result of the factor analysis on non-monetary factors and religiosity items. Then, the results of the multiple regression analysis are presented to find out the influence of the non-monetary factors on knowledge sharing behaviour.

Finally, the effect of religiosity as a moderating variable on the relationship between non-monetary factors and knowledge sharing behaviour is presented.

Respondents Characteristics

The Characteristics of the respondents showed that female respondents slightly outnumbered male respondents, 55% compared with male respondents 45%. Respondent’s age ranged between 20 to 51 years old.

The majority fell in the range of 20 to 30 years. Most of the respondents were Malaysians about 69.2%, while 30.8% respondents were from other countries. The characteristic profile of the respondents in terms of ethnicity showed that the majority were Malay 49.1%, followed by Chinese 11.8%, whereas 9.4% were Indian and 1.8% were from Others ethnicity.

The data demonstrates that more than three fourths of the respondents were Muslim, followed by Buddhists 9.2%, Hindus were 4.8%, and 7.2% were from other religious backgrounds. In term of education, the majority of the respondents were Masters’ students at 86.2%, while doctorate students were at 13.8%.

Factor analysis

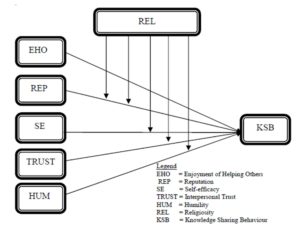

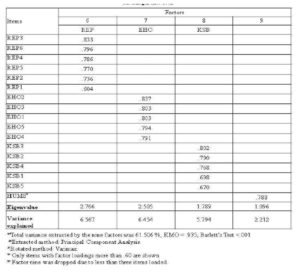

Factor analysis was conducted on the 42 items of non-monetary factors and 11 items of religiosity to determine the items underlay the dimensions measurement of the constructs.

Moreover, the analysis also done to summarise and reduce data among interrelated variables and come out with a few underlying factors to explain the correlation among those variables (Malhotra, 2007). The factor analysis performed and extracted nine factors with eigenvalue more than 1.0. These 9 factors explained 61.506 of the total variance.

Table 1 showed that factors 1, 2, 3, were loaded with eleven, nine, and 7 items respectively. Humility construct was split into two factors 4 and 5. Therefore, the six items under factor 4 was labelled as scholar humility and the other four items loaded under factor 5 was labelled as general humility. A scholar is knowledge seeker or a learned and knowledgeable person who has more knowledge in a particular area (Merriam-Webster, 2013).

Therefore to become a scholar one should continuous seeking knowledge through a long process of learning. This is in return releases a scholar from traits such as arrogance and over confidence (Ghosh, 2002). Thus, humbleness will be gained, because scholar knows that, although scholarship they acquire, still more thing remains to know (Boyer, 1996). Scholar humility is a trait which can be easily recognised in a scholar person, when they admitted their shortcoming and struggled to overcome it (Crigger &Godfrey, 2010).

This is an indication of scholar humility. This situation has evidence in Holy Quran. The Holy Quran says: “And they ask you, [O Muhammad], about the soul. Say, “The soul is of the affair of my Lord. And mankinds have not been given of knowledge except a little.”(Holy Quran15:85). In addition, Freeman (2004) as a scholar asserted that after thirty years journey of working life he found that he has achieved a progress from arrogance to humble, and became more compassionate, wiser, and tolerance in dealing with others.

These virtues consist of many good traits such as never hurt and offend others, having the readiness to apologise and bearing the responsibility to disseminate knowledge to others. However these attribute reflects scholar humility.

Factors six, seven, eight and nine were loaded with six, five, and five items respectively. The items with factor loadings of .60 and above were considered significant and below .60 were dropped from the factors interpretation as recommended by (Andersen & Herbertsson 2005; Chin 1998).

In addition, the item (HUM8) was loaded alone under factor nine, hence, dropped as according to Pallant (2007), three or more items loaded under one factor is preferable. The results showed that only four items were discarded (self-efficacy5, humility1, humility8, and humility9) while the remaining items were retained for further analysis.

In the reliability test, croanbach’s alpha of the construct was more than 0.79 which were quite acceptable (Nunnally, 1978).

Regression Analysis and Hypotheses Testing

The multiple regression technique was used to test the hypotheses of the direct relationship between the non-monetary variable and knowledge sharing behaviour and how independent variables predict the dependent variable, as well as to test the hypotheses of the moderating effects proposed.

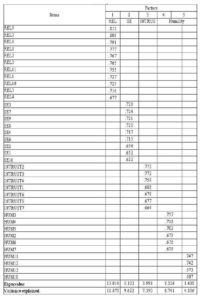

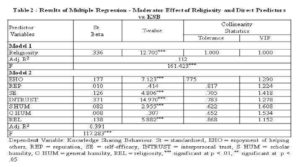

First, as seen in Table 2 the output showed that there were two models. The first model consisted of religiosity as a moderator construct with significant (F value = 161.423, p < 0.000 less than .01) with adj. R2 .112, indicating that 11.2% of the dependent variable was explained by religiosity and the standardised coefficient beta was (β =.336, t = 12.705, p < .01), showing that religiosity as a moderator had a predictor effect on the dependent variable, with positive sign.

The second model presented the seven independent variables (enjoyment of helping others, reputation, self-efficacy, interpersonal trust, scholar humility, general humility and religiosity) with one dependent variable (knowledge sharing behaviour) to determine the total variance explained by all the dependent variables. The F value was calculated and the regression model found it statistically significant at (F value = 117.283, p < 0.000 less than .01).

It is clear from the results that interpersonal trust has the strongest coefficient (β=.371, t = 14.970, p <.01), followed by the enjoyment of helping others (β= .177, t = 7.123, p < .01), religiosity (β = .138, t = 5.882, p <.01), self-efficacy (β= .126, t = 4.806, p < .01) and scholar humility (β=.082, t = 2.955, p .1) and general humility variable shows (β = .002, t = .175, p >.1), which means they have a positive sign of relationship with knowledge sharing behaviour but is not significant. Therefore, only four hypotheses were supported (H1a, H1c, H1d, and H1ea). Hypotheses H1b and Heb were not supported.

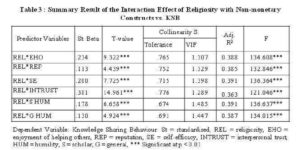

Second, is to test the moderating effect of religiosity on the relationship between non-monetary variable and knowledge sharing behaviour. Table 3 represents the summary of the regression analysis results of the interaction effect of religiosity as a moderator variable with the six independent variables (enjoyment of helping others, reputation, self-efficacy, interpersonal trust, scholar humility, and general humility).

The finding of the interaction effects of religiosity on knowledge sharing behaviour was significant with all the non-monetary factors. The finding suggested that religiosity is a strong construct that increases the propensity of the postgraduate students to share their knowledge with colleagues. The strongest effects were from the (REL*INTRUST) variable with standardised beta 0.381 followed by 0.234 for (REL*EHO), 0.200 for (REL*SE), 0.178 for (REL*S HUM), 0.130 for (REL*G HUM), and 0.113 for (REL*REP) respectively. Therefore, the result supports hypothesis H2.

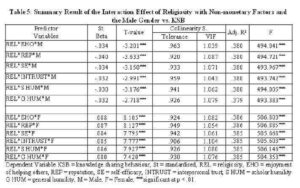

Third, the result of multiple regressions shows the effect of religiosity among different ethnicity of respondents on the relationship between predicting variables and knowledge sharing behaviour. Table 5 represents the summary of the interaction effects.

The effect of religiosity among the Malay ethnic group on the relationship between non-monetary factors and knowledge sharing behaviour, implying that religiosity among Malay ethnic group is fundamental factor in motivating knowledge sharing behaviour. In contrast, as seen in Table 4, Religiosity among Chinese ethnic group was not significant to words knowledge sharing behaviour, indicating that religiosity does not play an important role in motivating the Chinese to share their knowledge. In addition, the result showed that the religiosity among Indian ethnic group is crucial factor in motivating them to share their knowledge.

Finally, religiosity among Others was not found significant related to knowledge sharing behaviour. These findings supporting the hypotheses H3a, H3c, whereas, hypothesis H3b and H3d were not supported.

Fourth, the finding of this study in Table 5 showed the influence of religiosity between different genders male and female of postgraduate students. All the interaction effect were significant but with negative sign indicating that male gender who are religious and believe in non-monetary factors are less frequently sharing their knowledge.

On the other hand religiosity among female were positively related to knowledge sharing behaviour indicating that religious female who believes in non-monetary factors are more frequently sharing their knowledge. This result confirmed H4a and H4b.

According to Hair et al. (2006) a high variance inflation level indicates that there is multicollinearity among the independent variables. The tolerance level must be close to 1.0, or more than 0.1, whereas the level of variance inflation factor must be below 10.0 (Hair et al., 2006). From the above result of the regression analyses no multicollinearity was detected.

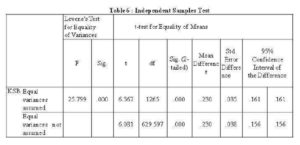

Fifth, T-test was used to differentiate between Malaysian and International students in terms of knowledge sharing behaviour. The result in Table 6 indicates that the F-test was significant at (p< 0.05). Consulting the t-value significance from the output, it was significant with (t = 6.081, p <.05) which indicates rejection of the null hypothesis (equal variance assumed) and acceptance of the alternative hypothesis.

And the t-test for equality of means was significant, which shows that there was a difference between the means. This result answered the hypothesis H5.

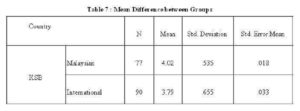

Table 7 shows the difference of the means between the two groups. The mean value of the Malaysian group (4.02) was greater than the mean value of the International group (3.79).

Discussion and Conclusion

This study was carried out to investigate non-monetary factors that predict knowledge sharing behaviour among postgraduate students. Based on prior studies in knowledge sharing and knowledge sharing behaviour, this study proposed that non-monetary factors motivate and encourage postgraduate students to share their knowledge with colleagues.

The result of the data analysis revealed that there was significant relationship between the enjoyment of helping others, self-efficacy, interpersonal trust, scholar humility and religiosity with knowledge sharing behaviour.

To a certain extent, the findings of this study asserts that the non-monetary factors (enjoyment of helping others, self-efficacy, interpersonal trust and scholar humility) were highly associated to knowledge sharing behaviour and consistent to prior studies (Lin, 2007; Hsu & Lin 2008; Kankanhalli et al., 2005; Wasko & Faraj, 2005).

No significant evidence was found to support the relationship between reputation, general humility and knowledge sharing behaviour. This suggests that the effect of reputation and general humility were rather limited.

In addition, the present study investigates the interaction effects of religiosity with ethnicities on the relationship between non-monetary factors and knowledge sharing behaviour, which has not been investigated before.

The findings reveal that the interaction effect of religiosity with Malay and Indian ethnic groups with non-monetary factors were significantly related to knowledge sharing behaviour and supported the hypothesis. In contrast, the interaction effect of religiosity with Chinese and Others ethnicity on the relationship between non-monetary factors and knowledge sharing behaviour was not significant, and showed insufficient evidence to support the hypotheses.

The justification to these findings might be due to the culture differences of the Chinese, who are highly motivated by financial rewards and appear to have less concern regarding religious issues (Rashid & Ho, 2003). It becomes visible that religion does not have much significant impact on Chinese behaviour (Sian, 2009).

This isolation might have influenced their behaviour and discouraged them from mingling with others. Thus, even those who are committed to their religion or beliefs do not trust others and lack humility while dealing with others, since they do not seek a high status among other races.

In the case of the interaction effect of religiosity with the Others ethnicity and non-monetary

factors related to knowledge sharing behaviour, the findings were not significant. The rationale behind this might be due to their different perception of religiosity in their traditional religions, principles and beliefs. Moreover, according to the data collected, most of the Others respondents were free-thinkers and were not much committed to a particular religion.

Therefore, the virtue of religiosity does not spread in their culture and community, and thus, religiosity does not influence their behaviour towards knowledge sharing. In addition, the total of the ‘Others’ respondents in this study was low. Only 23 respondents subscribed to this study, which is why the result might not be significant.

These findings indicate that religious male respondents, who believe in non-monetary factors as a critical determinant for knowledge sharing behaviour, are less likely to share their knowledge with colleagues. This negative relationship might be due to competitiveness of the male gender who wants to establish their positions to their female counterparts.

As Fisher and Gregoire (2006) showed in their findings, males usually work competitively in a mixed environment (men and women) to emphasise their dominance, whereas females are less likely to behave competitively and can be classified as cooperative (Gneezy et al., 2003). In this study, women generally share their knowledge willingly when they are in a positive workplace compared to males.

The finding revealed that males may have less willingness to share their knowledge with others, is consistent with the prior study of Lin (2006). An alternative explanation for the negative significant relationship between religiosity with males and knowledge sharing behaviour is the lack of interpersonal relationship. In this sense, Miller and Karakowsky (2005) noted that men are less concerned about interpersonal relationships, whereas, on the other side, women are more sensitive to others’ ideas, opinions and knowledge.

The reason why males may not share their knowledge could be due to the high concern to their ego or to hide their weaknesses from others who are seeking information. Or that it is simply incongruent with the male role, while it is different in the situation of females, who are more likely to ask for information (Miller & Karakowsky, 2005). Another reason might be male chauvinism that describes the superiority of the male (Mansbridge & Flaster, 2007). Or the fact that men are less friendly than women.

Limitation

The study focused on a few non-monetary factors that motivate knowledge sharing behaviour which explained 35.7% of the variance of the dependent variable. Therefore, future studies can investigate other factors to explain the remaining part of the variance such as subjective norm and personality traits.

The study did not include the graduate students of private universities or other respondents who have a great influence in knowledge sharing behaviour in universities such as professors, doctors and academicians. Therefore, they can be investigated in future studies.

Implication of the study

The main contribution of this study is to formulate a theoretical framework to reflect the relationship between non-monetary factors and the behaviour of knowledge sharing. In addition, this study introduced, for the first time, the humility construct to be used as one of the non-monetary factors in predicting knowledge sharing behaviour.

Religiosity as a moderating variable was added to the theoretical framework in order to examine its effect on the relationship between non-monetary factors and knowledge sharing behaviour.

This moderating relationship might be considered as a new contribution. In addition, this study enriches the area of knowledge sharing behaviour and contributes to the literature by highlighting the significant role of religiosity as a moderator in the relationship between non-monetary factors and knowledge sharing behavior, which has not been studied before in the context of knowledge sharing behaviour. Moreover, the interaction effects of religiosity with Malaysian ethnicities and different gender group on knowledge sharing behaviour can be considered as an extension to the literature review in this field.

In terms of practical implications, the findings of the study have provided various practical implications to strength and promote the behaviour of knowledge sharing among postgraduate students.

Since non-monetary factors can influence knowledge sharing behavior, it is critical for universities to allocate resources to deal with the factors that have a strong influence on postgraduate’s behavior toward knowledge sharing in order to formulate their strategies, plans, and programmes.

They should set up a suitable social environment to increase social interaction behaviour such as a knowledge sharing club, scientific club or culture club, to enable postgraduate students to build a strong social relationship with colleagues and activate the hidden values, morality and personal characteristics to strengthen the behaviour of knowledge sharing.

In addition, they should take the initiative to promote the non-monetary factors to raise the view of knowledge sharing behaviour among postgraduate students. Moreover, they should seek suitable mechanisms to enhance the spiritual feelings which encourage the behaviour of knowledge sharing.

References

1. Abrams, L. C., Cross, R., Lesser, E., & Levin, D. Z. (2003). “Nurturing interpersonal trust in knowledge-sharing networks”. Academy of Management Executive, 17(4), 64-77.

Publisher – Google Scholar

2. Andersen, T. M., & Herbertsson, T. T. (2005). “Quantifying globalization”. Applied Economics, 37(10), 1089-1098.

Publisher – Google Scholar

3. Bakker, M., Leenders, R., Gabbay, S. M., Kratzer, J., & Van Engelen, J. M. L. (2006). “Is trust really social capital? Knowledge sharing in product development projects”. The Learning Organization, 13(6), 594-605.

Publisher – Google Scholar

4. Bartol, K. M., & Srivastava, A. (2002). “Encouraging knowledge sharing: the role of organizational reward systems”. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 9(1), 64-76.

Publisher – Google Scholar

5. Berends, H. (2005). “Exploring knowledge sharing: moves, problem solving and justification”. Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 3(2), 97-105.

Publisher – Google Scholar

6. Blau, P. M. (1964). Power and exchange in social life. New York: J Wiley & Sons.

Publisher – Google Scholar

7. Bock, G. W., & Kim, Y. G. (2002). “Breaking the myths of rewards: An exploratory study of attitudes about knowledge sharing”. Information Resources Management Journal, 15(2), 14-21.

8. Bock, G. W., Zmud, R. W., & Kim, Y. G. (2005). “Behavioral intention formation in knowledge sharing: examining the roles of extrinsic motivators, social-psychological forces, and organizational climate”. MIS Quarterly, 29(1), 87-111.

Google Scholar

9. Boyer, E. L. (1996). From scholarship reconsidered to scholarship assessed. Quest, 48(2), 129-139.

Google Scholar

10. Cheng, M. Y., Ho, J. S. Y., & Lau, P. M. (2009). “Knowledge sharing in academic institutions: a study of Multimedia University Malaysia”. Electronic Journal of Knowledge Management, 7(3), 313-324.

Google Scholar

11. Chin, W. W. (1998). “Commentary: Issues and opinion on structural equation modeling”. Mis Quarterly, 22(1), 7-16. Google Scholar

12. Choi, B., Poon, S. K., & Davis, J. G. (2008). “Effects of knowledge management strategy on organizational performance: a complementarity theory-based approach”. Omega, 36(2), 235-251.

Publisher – Google Scholar

13. Crigger, N., & Godfrey, N. (2010). “The importance of being humble”. Advances in Nursing Science, 33(4), 310.

Publisher – Google Scholar

14. Davenport, T., & Prusak, L. (1998). Working knowledge: Managing what your organization knows.Boston:Harvard Business School Press.

Google Scholar

15. Delener, N. (1990). “The effects of religious factors on perceived risk in durable goods purchase decisions”. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 7(3), 27-38.

Publisher – Google Scholar

16. Delener, N. (1994). “Religious contrasts in consumer decision behaviour patterns: their dimensions and marketing implications”. European Journal of Marketing, 28(5), 36-53.

Publisher – Google Scholar

17. Emmons, R. A. (2000). “Is spirituality an intelligence? Motivation, cognition, and the psychology of ultimate concern”. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 10(1), 3-26.

Publisher – Google Scholar

18. Endres, M. L., Endres, S. P., Chowdhury, S. K., & Alam, I. (2007). “Tacit knowledge sharing, self-efficacy theory, and application to the Open Source community”. Journal of Knowledge Management, 11(3), 92-103.

Publisher – Google Scholar

19. Essoo, N., & Dibb, S. (2004). “Religious influences on shopping behaviour: An exploratory study”. Journal of Marketing Management, 20(7), 683-712.

Publisher – Google Scholar

20. Estephan, A. S. (2005). The relationship between marital humility, marital communication, and marital satisfaction PhD, Texas Southern University, Texas.

21. Exline, J. J., & Geyer, A. L. (2004). “Perceptions of humility: A preliminary study”. Self and Identity, 3(2), 95-114.

Google Scholar

22. Fisher, R. J., & Grégoire, Y. (2006). “Gender differences in decision satisfaction within established dyads: Effects of competitive and cooperative behaviors”. Psychology and Marketing, 23(4), 313-333.

23. Freeman, J. M. (2004). “On learning humility: a thirty year journey”. Hastings Center Report, 34(3), 13-16.

Publisher – Google Scholar

24. Ghosh, S. (2002). Humbleness as a practical vehicle for engineering ethics education. Paper presented at the Frontiers in Education, 2002. FIE 2002. 32nd Annual.

Google Scholar

25. Gist, M. E., & Mitchell, T. R. (1992). “Self-efficacy: A theoretical analysis of its determinants and malleability”. Academy of Management Review, 17(2)183-211.

Publisher – Google Scholar

26. Gneezy, U., & Rustichini, A. (2004). “Gender and competition at a young age”. The American Economic Review, 94(2), 377-381.

Google Scholar

27. Gorry, G. A. (2008). Sharing knowledge in the public sector: two case studies. Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 6(2), 105-111.

Publisher – Google Scholar

28. Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson, & Tatham. (2006). Multivariate Data Analysis (6 th ed.). Pearson Education, Inc. New Jersey, USA

Google Scholar

29. Hicks, J. A., & King, L. A. (2008). “Religious commitment and positive mood as information about meaning in life”. Journal of Research in Personality, 42(1), 43-57.

Publisher – Google Scholar

30. Holy-Qur’an. Interpretation of the Meanings of the Noble Qur’an in the English Language. Retrieved Jan 25th 2013, from http://quran.com/

31. Hsu, C. L., & Lin, J. C. C. (2008). “Acceptance of blog usage: The roles of technology acceptance, social influence and knowledge sharing motivation”. Information & Management, 45(1), 65-74.

Publisher – Google Scholar

32. Hsu, M. H., Ju, T. L., Yen, C. H., & Chang, C. M. (2007). “Knowledge sharing behavior in virtual communities: the relationship between trust, self-efficacy, and outcome expectations”. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 65(2), 153-169.

Publisher – Google Scholar

33. Jain, P. (2007). “An empirical study of knowledge management in academic libraries in East and Southern Africa”. Library Review, 56(5), 377-392.

Publisher – Google Scholar

34. Kankanhalli, A., Tan, B. C. Y., & Wei, K. K. (2005). “Contributing knowledge to electronic repositories: an empirical investigation”. MIS Quarterly, 29(1), 113—143.

Google Scholar

35. Kilroy, J. J. (2009). Development of seven leadership behavior scales based upon the seven leadership values inspired by the beatitudes. PhD, Regent University, USA.

36. Kuo, F. Y., & Young, M. L. (2008). “Predicting knowledge sharing practices through intention: A test of competing models”. Computers in Human Behavior, 24(6), 2697-2722.

Publisher – Google Scholar

37. Lee, H., & Choi, B. (2003). “Knowledge management enablers, processes, and organizational performance: An integrative view and empirical examination”. Journal of Management Information Systems, 20(1), 179-228.

Google Scholar

38. Lee, J. N. (2001). “The impact of knowledge sharing, organizational capability and partnership quality on IS outsourcing success”. Information & Management, 38(5), 323-335.

Publisher – Google Scholar

39. Lin, H. F. (2006). “Impact of organizational support on organizational intention to facilitate knowledge sharing”. Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 4(1), 26-35.

Publisher – Google Scholar

40. Lin, H. F. (2007). “Knowledge sharing and firm innovation capability: an empirical study”. International Journal of Manpower, 28(3/4), 315-332.

Publisher – Google Scholar

41. Malhotra, N. K. (2007). Marketing Reseatrch (Fifth Edition ed.). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, Pearson Education, Inc.

42. Mallasi, H. I. (2012). “Knowledge Sharing Behaviour Among Malaysian Students”. PhD, University of Malaya, Malaysia.

43. Mansbridge, J., & Flaster, K. (2007). “The Cultural Politics of Everyday Discourse: The Case of “Male Chauvinist”.Critical Sociology, 33(4), 627-660.

Publisher – Google Scholar

44. Merriam-Webster. (2013). In Merriam Webster Dictionary [Online].[Retrieved 31st Jan 2013] Available: http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary

45. Miller, D. L., & Karakowsky, L. (2005). “Gender influences as an impediment to knowledge sharing: when men and women fail to seek peer feedback”. The Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied, 139(2), 101-118.

Publisher – Google Scholar

46. Mokhlis, S. (2006b). “The influence of religion on retail patronage behaviour in Malaysia”. PhD, University of Stirling, UK.

Google Scholar

47. Mokhlis, S. ( 2006a). “The effect of religiosity on shopping orientation: an exploratory study in Malaysia”. Journal of American Academy of Business, Cambridge, 9(1), 64-74.

48. Muhamad, R., Devi, S. S., & Mu’min, A. G. A. (2006). “Religiosity and the Malay Muslim Investors in Malaysia: An Analysis on Some Aspects of Ethical Investment Decision”. Advances in Global Business Research 3(1), 197-206.

49. Nonaka, I. (1991). “The knowledge-creating company”. Harvard business review, 69(6), 96-104.

Google Scholar

50. Noor, N. M., & Salim, J. (2011). “Factors Influencing Employee Knowledge Sharing Capabilities in Electronic Government Agencies in Malaysia”. International Journal of Computer Science Issues, 8(4), 106-114.

Google Scholar

51. Nunnally, J. (1978). Psychometric theory: New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company.

52. Ong, F. S., & Moschis, G. P. (2006). “Religiosity and consumer behavior: a crosscultural study”. [Online].[Retrieved on 12th Aug 2012].Available:http://scholar.google.com.my/scholar?hl=en&q=Ong+fon+sim+and+Moschis&as_sdt=0%2C5&as_ylo=&as

_vis=0

Publisher – Google Scholar

53. Pai, J. C. (2006). “An empirical study of the relationship between knowledge sharing and IS/IT strategic planning (ISSP)”. Management Decision, 44(1), 105-122.

Publisher – Google Scholar

54. Pallant, J. (2007). SPSS survival manual: Astep by step guide to data analysis using SPSS for windows (Third Edition ed.). Berkshire England: Open University Press, Mc Graw Hill.

55. Poulson, R. L., Eppler, M. A., Satterwhite, T. N., Wuensch, K. L., & Bass, L. A. (1998). “Alcohol consumption, strength of religious beliefs, and risky sexual behavior in college students”. Journal of American College Health, 46(5), 227-232.

Publisher – Google Scholar

56. Rashid, M. Z. A., & Ho, J. A. (2003). “Perceptions of business ethics in a multicultural community: The case of Malaysia”. Journal of Business Ethics, 43(1/2), 75-87.

Publisher – Google Scholar

57. Rosendaal, B. (2009). “Sharing knowledge, being different and working as a team”. Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 7(1), 4-14.

Google Scholar

58. Rowden, T. (2009). Humility as catalyst of client change: a delphi study. PhD, Texas Tech University, USA.

59. Sherman, N. (1991). The fabric of character: Aristotle’s theory of virtue:Oxford University Press, UK.

60. Sian, L. F. (2009). An Investigation into the Impact of Income, Culture and Religion on Consumption Behaviour: A Comparative Study of the Malay and the Chinese Consumers in Malaysia. PhD, University of Exeter, UK.

61. Sood, J., & Nasu, Y. (1995). “Religiosity and nationality:: An exploratory study of their effect on consumer behavior in Japan and the United States”. Journal of Business Research, 34(1), 1-9.

62. Tangney, I. P. (2000). “Humility: Theoretical perspectives, empirical findings and directions for future research”. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 19(1), 70-82.

Publisher – Google Scholar

63. Vera, D., & Rodriguez-Lopez, A. (2004). “Strategic virtues: Humility as a source of competitive advantage”. Organizational Dynamics, 33(4), 393-408.

64. Wasko, M., & Faraj, S. (2000). “It is what one does”: why people participate and help others in electronic communities of practice”. The Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 9(2), 155-173.

Publisher – Google Scholar

65. Wasko, M. M. L., & Faraj, S. (2005). “Why should I share? Examining social capital and knowledge contribution in electronic networks of practice”. Mis Quarterly, 29(1), 35-57.

Google Scholar

66. Worthington Jr, E. L., Wade, N. G., Hight, T. L., Ripley, J. S., McCullough, M. E., Berry, J. W., . . . O’Connor, L. (2003). “The Religious Commitment Inventory–10: Development, refinement, and validation of a brief scale for research and counseling”. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 50(1), 84-96.

Publisher – Google Scholar

67. Yi, J. (2009). “A measure of knowledge sharing behavior: scale development and validation”. Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 7(1), 65-81.

Publisher – Google Scholar

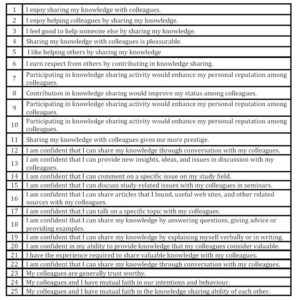

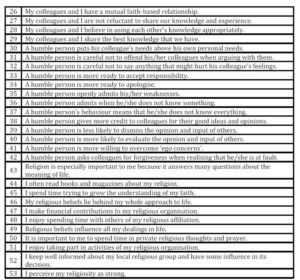

Appendix 1

Measurement Items