The role of financial and trade linkages in transmission of shocks on output comovements

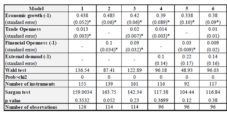

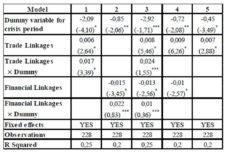

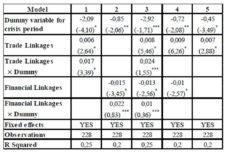

In order to test the role of financial and trade linkages in transmission of shocks on output comovements the panel model described in equation (4) was estimated. The Hausman test conducted on these estimations indicates the utilization of fixed effects model estimator.

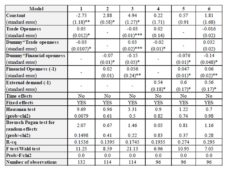

The estimation results indicate that during normal times, an increase in financial flows between different regions tends to lower comovements between them (Table 3, models 2 to 4). The coefficient corresponding to the financial channel is econometrically and statistically significant. The sign of the coefficient is negative suggesting that increased financial flows determine a decreasing of economic growth synchronization during normal times. If financial channel is active and the economy operates in normal conditions, investors tend to diversify the placements looking for the regions were the capital is more productive.

The results are in line with relevant literature, which indicate that financial integration rises risk sharing and tend to decrease the volatility in consumption (for example, Bekaert, Campbell, and Lundbad (2011) or Kalemli-Ozcan, Sorensen, and Yosha (2003), among others). However, during crisis the way in which the financial channel is working is changing due to the fact that financial shocks are transmitted through financial linkages. Regions that experience a high degree of integration, especially through the banking system, had a significant increase in their economic growth comovement during the crisis period. Although the financial channel allows efficient capital allocation in normal conditions, during crisis it facilitates the transmission of the financial shocks across different regions. The total effect of financial linkages on output comovement is negative but its effect during the global crisis from 2008 — 2009 was reversed, becoming positive, as the sign of the coefficient corresponding to financial linkages multiplied with dummy variable indicate (models 2 and 3). However, the total effect is still negative suggesting that the crisis weakened the negative relationship between financial integration and output comovement.

Table 3: Comovements and Trade and Financial linkages between CEE countries and EU

Note: This table reports panel (CEE countries with EU pairs) fixed-effect estimates for the period 2004 Q1 — 2013 Q3 using 6 country pairs. Slovakia was excluded from the panel due to data availability issues regarding direct investments quarterly flows having as partner EU27 countries. The dependent variable is the comovement of real GDP growth between each CEE country and EU measured using the instantaneous synchronization index. The results are not changing sensible when the comovement measure is changed with one of the different alternatives described earlier in the paper. The dummy variable for the crisis equals 1 during the 2008 Q3 — 2009Q2 interval and 0 everywhere else. Trade linkages are measured by the bilateral real exports and imports of each country and EU expressed as a share of real GDP. Financial linkages are measured by the bilateral real foreign direct and portfolio investments flows of each country and EU expressed as a share of real GDP. In parenthesis are reported T statistics. *, **, ***, denote significance at the 1 percent, 5 percent and 10 percent levels, respectively.

The crisis dummy captures a significant part of the spike in synchronization coefficient, indicating that there are some other factors, apart from the financial and trade linkages, which contributed to spreading of the negative effects of the crisis affecting the synchronized output fall in the analysed economies. Bacchetta and van Wincoop (2013) suggested that global panic and self-fulfilling expectations significantly contributed to the spread of the negative effects of the global financial crisis.

The measured influence of trade linkages is significantly more reduced compared with the impact of financial linkages also due to the limited time variation in quarterly trade data relative to financial data (see model 5 for example).

Conclusion

Recent macroeconomic literature has paid much attention to studying the effects of commercial and financial openness on economic growth. However, scant empirical studies devoted their work to analysing this phenomenon in Central and Eastern European countries.

Therefore this paper brings a contribution to this literature by studying the relationship between the degree of openness and economic growth in seven emerging economies from Central and Eastern European countries using both static and dynamic panel data estimation methods. The results point towards a positive contribution of international trade and foreign direct investments on economic growth although the magnitude and the significance of the impact depend on the estimation method and also on the control variables we include in order to provide a better explanation of the real economic growth.

However, the trade and financial linkages may significantly contribute to the transmission of negative shocks from more developed economies towards emerging countries and significant synchronized GDP fall may emerge.

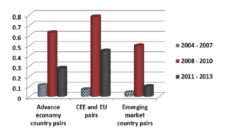

The main findings indicate that higher financial integration tends to reduce output synchronization during normal economic conditions while during crises periods the regions which are more financially linked experience greater synchronization.

Preserving financial stability is essential in order to prevent synchronized GDP growth collapses in many countries. The transmission mechanism of financial shocks on economic growth synchronization during normal periods is substantially different than during crisis. If during normal periods the capital flows are channelized towards emerging markets which offer greater yields determining output divergence within regions with strong financial linkages, during crisis the financial channels favours the propagation of adverse shocks contributing to output fall synchronization. That is way it is important to safeguard the benefits of financial integration through minimizing consequent risks by the instrumentality of better prudential oversight and policy coordination across the entire international financial system.

Acknowledgment

„This paper was co-financed from the European Social Fund, through the Sectorial Operational Programme Human Resources Development 2007-2013, projects numbers: POSDRU/159/1.5/S/138907 “Excellence in scientific interdisciplinary research, doctoral and postdoctoral, in the economic, social and medical fields -EXCELIS” and POSDRU/159/1.5/S/134197 “Performance and excellence in doctoral and postdoctoral research in Romanian economics science domain”, coordinator The Bucharest University of Economic Studies”

References

1. Acharya, Viral V. and Schnabl, P. (2010), ‘Do Global Banks Spread Global Imbalances? Asset-Backed Commercial Paper during the Financial Crisis of 2007—09,’ IMF Economic Review, 58(1), 37—73.

Publisher – Google Scholar

2. Auerbach, A. and Gorodnichenko, Y. (2013), ‘Output Spillovers from Fiscal Policy,’ American Economic Review, 103(3),141-46.

3. Bacchetta, P. and van Wincoop, E. (2013), ‘Sudden Spikes in Global Risk,’ Journal of International Economics, 89(2), 511—21.

Publisher – Google Scholar

4. Bajwa, S. and Siddiqi, M. (2011), ‘Trade openness and its effects on economic growth in selected South Asian Countries: A Panel Data Study,’ World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology.

5. Beetsma, R., Giuliodori, M. and Klaassen, F. (2006), ‘Trade Spillovers of Fiscal Policy in the European Union: A Panel Analysis,’ Economic Policy, 21(48), 639—87.

Publisher – Google Scholar

6. Bekaert, G., Campbell, H.R. and Lundblad, C. (2011), ‘Financial Openness and Productivity,’ World Development, 39( 1), 1—19.

Publisher – Google Scholar

7. Canova, F. (1998), ‘Detrending and Business Cycle Facts,’ Journal of Monetary Economics, 41(. 3), 475—512.

Publisher – Google Scholar

8. Chang, R., Kaltani, L. and Loayza, N. (2009),‘Openness is good for economic growth: The role of policy complementaries,’ Journal of Developed Economics, 90, 33-49

Publisher – Google Scholar

9. Claessens, S., Tong, H. and Zuccardi, I. (2012), ‘Did the Euro Crisis Affect Non-financial Firm Stock Prices through a Financial or Trade Channel?,’ IMF Working Paper No. 11/227 (Washington: International Monetary Fund).

10. di Giovanni, J. and Shambaugh, J.C. (2008), ‘The Impact of Foreign Interest Rates on the Economy: The Role of the Exchange Rate Regime,’ Journal of International Economics, 74 (2), 341—61.

Publisher – Google Scholar

11. Frankel, J. and Rose, A.(1998), ‘The Endogeneity of the Optimum Currency Area Criteria,’ Economic Journal, 108( 449), pp. 1009—25.

Google Scholar

12. Fratzscher, M. (2012), ‘Capital Flows, Push versus Pull Factors and the Global Financial Crisis,’ Journal of International Economics,88(2), pp. 341—56.

Google Scholar

13. Giannone, D., Lenza, M. and Reichlin, L. (2010), ‘Did the Euro Imply More Correlation of Cycles?’ in Europe and the Euro, ed. by Alberto Alesina and Francesco Giavazzi (Chicago: University of Chicago Press), 141—67.

14. Grossman, G.M. and Helpman, E. (1991), ‘Trade, knowledge spillovers and growth‘, NBER Working Paper 3485.

Google Scholar

15. International Monetary Fund (2013),‘World Economic Outlook, Transitions and Tensions’, October 2013, http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2013/02/.

16. Kalemli-Ozcan, S., Sorensen, B.E. and Yosha, O. (2003), ‘Risk Sharing and Industrial Specialization: Regional and International Evidence,’ American Economic Review, 93( 3), 903—18.

Publisher – Google Scholar

17. Kalemli-Ozcan, S., Papaioannou, E. and Perri, F. (2013), ‘Global Banks and Crisis Transmission,’ Journal of International Economics, 89, 495—510.

Publisher – Google Scholar

18. Kalemli-Ozcan, S., Papaioannou, E. and Peydro-Alcalde, J.L. (2009), ‘Financial Integration and Risk Sharing: The Role of Monetary Union, in The Euro at Ten: Fifth European Central Banking Conference, ed. by Bartosz Maćkowiak, Francesco Paolo Mongelli, Gilles Noblet, and Frank Smets (Frankfurt: European Central Bank).

19. Rodriguez, F and Rodrick, D. (2001),’Trade Policy and economic growth: A Skeptic’s Guide to the Cross-National Evidence’ NBER Macroeconomics Annual 2000, 15, MIT Press, 26y1-325.

Google Scholar

20. Romer, D. (1993),’Openness and inflation. Theory and evidence’ Quarterly Journal of Economics 108 (November), 869-903.

21. Ulasan, B. (2012), ’Openness to international trade and economic growth: A cross-country empirical investigation’ Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey, Discussion Paper.

Google Scholar

22. Yanikkaya, H. (2003),’Trade openness and economic growth: a cross-country empirical investigation’, Journal of Development Economics, 72, 57-89.

Publisher – Google Scholar

23. Zeren, F. and Ari, A. (2013),’Trade openness and economic growth: A panel causality test,’ International Journal of Business and Social Science, 4(9).

Google Scholar