Testing for Normality and Outliers

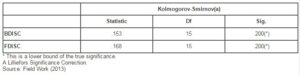

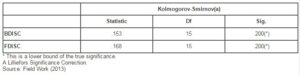

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used for normality, while the box-plot was used to test for outliers. The normality test result shown on table 5 reveals that the two variables used in this study namely; BDISC and FDISC did not violate the normality assumptions, since their K-S coefficients have sig. values greater than the 0.05 benchmark.

Table 5: Tests of Normality

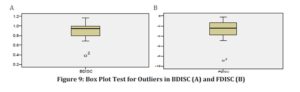

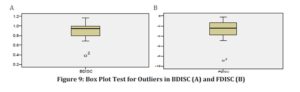

In testing for outliers, the box plots technique was employed. Figure 9 shows the box plots for BDISC (A) and FDISC (B). The result revealed that one outlier in each case with ID numbers 2 and 2 representing 0.3779 for BDISC, and -8.9262 for FDISC respectively. The absence of apteryx on the outliers indicate that the outliers do not have strong influence on the data set, and as such will not significantly distort the result of the analyses

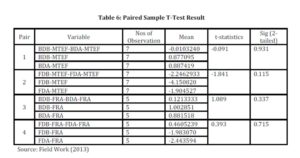

The Paired Sample T-Test

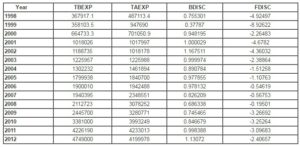

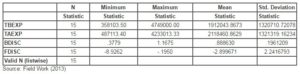

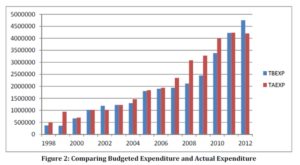

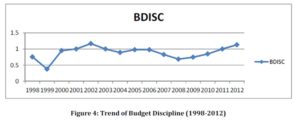

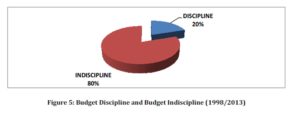

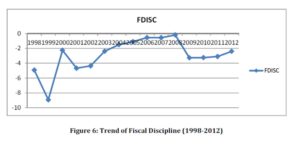

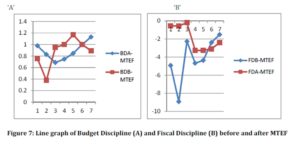

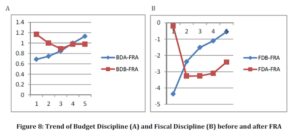

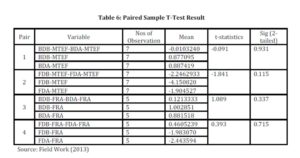

The paired sample T-test (pre-test/post-test design) was employed to measure the impact of Medium Term Expenditure Framework (MTEF), and Fiscal Responsibility Act (FRA) on Budget Discipline (BDISC), and Fiscal Discipline (FDISC) in Nigeria. With respect to MTEF, data for seven (7) years before its adoption (1998-2004), and seven (7) years after its adoption (2006-2012) were used in the analysis. The result in table 7 revealed a t-value of -0.091 (sig. = 0.931) for pair 1 (BDB-MTEF/BDA-MTEF), and a t-value of -1.841 (sig. = 0.115) for pair 2 (FDB-MTEF/FDA-MTEF). These results indicate that there is no statistically significant difference in budget discipline (BDISC), and fiscal discipline (FDISC) seven years before and seven years after the adoption of MTEF in Nigeria. The result favours the proposition that MTEF had not significantly impacted on the quality of budget management in Nigeria. However, the mean budget discipline increased marginally in absolute terms from 0.877095 (pre-MTEF) to 0.887419 (post MTEF), implying that MTEF have had some practical impact on budget discipline, but the change is not large enough to be considered as been statistically significant. The mean of fiscal discipline also demonstrated an increase in absolute terms from -4.150820 (pre-MTEF) to -1.002851 (post-MTEF). But like in budget discipline, the increase was not large enough to be statistically significant.

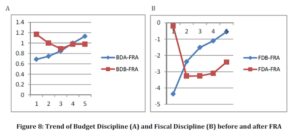

Similarly, with respect to Fiscal Responsibility Act (FRA) enacted in 2007, the result indicates no statistically significant difference in budget discipline and fiscal discipline, five years before and five years after the enactment of FRA in Nigeria. In other words, the enactment of Fiscal Responsibility Act 2007 had not influenced the quality of budget management in Nigeria in any significant way in support of the null hypothesis of this study. This is evidenced in the t-statistics, and their associated significance values of 1.089 (sig. = 0.337), and 0.393 (sig. = 0.715), for pair 3 (BDB-FRA/BDA-FRA), and pair 4 (FDB-FRA/FDA-FRA) respectively.

These results negate the expectations of economic managers and proponents of MTEF who had believed that MTEF is the key to achieving budget/fiscal discipline, and better operating efficiencies over the medium term. It is, however, in consonance with the testimony of Nussle (2012) that “the budget process chosen is less important than the political leadership provided”; or that it is not the tools, but the craftsman that makes the difference in the outcome. Going by this testimony, it can be inferred that budgetary reforms will be effective and impact the quality of budget, to the extent that the political leaders allow. It also tallies with the view that good governance and good budgeting are intertwined. In other words, the quality of a government can be x-rayed from the quality of its budgetary management (Ben-Caleb & Agbude, 2012). After all, the major attributes of good budgeting namely; effectiveness, efficiency, transparency, accountability and discipline are also ingredients of good governance, which if demonstrated, can engender value to the nation and the people (United Nations, 2007; Kaufman and Kraay, 2008).

Conclusion and Recommendations

This paper was fixated on the empirical evaluation of the impact of budgetary reforms especially MTEF, and FRA on the quality of budget management in Nigeria. Utilising both descriptive and inferential analyses, the paper achieved its aim; hence, we conclude that budget reforms had not had any significant influence on the Nigerian budget management. In other words, the MTEF and FRA had not been able to tame the spate of indiscipline in Nigeria’s budgetary process. However, it is necessary to state that the reforms themselves are not as much a problem than the “will” to enforce and implement the reforms. This is in tandem with the observation that most policies rolled out in developing nations, including Nigeria, do not achieve their desired result (Makinde, 2005). It is this policy ‘expectation gap’ that constitutes the real problem in Nigeria.

Therefore, in order to bridge the gap between policy intentions and their actual achievement, and allow the impact of reforms to be visible in Nigeria, the following recommendations are made: first, there should be a deliberate effort to imbibe the culture of discipline among all the responsibility officers in government. This will eschew the iniquitous impact of indiscipline on the economy. Secondly, the Appropriation Act (budget) like all other Acts of the National Assembly should be accorded the same legal weight. This will imply that the violation of the budget rules should be appropriately sanctioned. Thirdly, the government should provide the leadership and political will to enforce the provisions of FRA, MTEF and all other public sector reforms. Also, proper monitoring of expenditure will go a long way to discourage opportunistic behaviours, as well as other innovative ways of short circuiting or circumventing expenditure control as well as corruption

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

Reference

1. Aruwa, S A. (2004) ‘Nigerian Budgeting Process and the Magnitude of Budget Variances’, The Academy Journal of Defence Studies, 13(3), 12-35.

2. Ben-Caleb, E and Agbude, GA. (2012), ‘Good Budgeting and Good Governance: A Comparative Discourse’, The Public Administration and Social Policies Review 2(9), 49-59.

3. Ben-Caleb, E and Agbude, GA. (2013), ‘Budget Discipline in Nigeria: A Critical Evaluation of Military and Civilian Regimes’, Economica, 9(1), 91-101.

Google Scholar

4. Bengali, K., (2004), ‘Budgeting for Poverty Reduction’, A Background Paper presented as a part of the Pakistan Legislative Strengthening Consortium (PLSC); Pakistan Institute of Legislative Development and Transparency (PILDAT). (Retrieved April 3, 2012), http://www.millat.com/democracy/Budget/Background_paper_Poverty.pdf

5. Brumby, J (1998), Chapter 16: Budgeting reforms in OECD member Countries (Online). (Retrieved July 18, 2013), http://www.internationalbudget.org/wp-content/uploads/Budgeting-Reforms-in-OECD-Member-Countries.pdf

6. Garba, A.G. (2011), ‘The Institutional Framework for Budgeting in Nigeria:

Implications, Limitations and Required Actions by Government, Citizens and the NES’ Paper Presented at the NES Budget Seminar, 31st May 201, CIBN Building, VI, LAGOS.

7. Government Finance Officers Association (GFOA) (1999), ‘Recommended Budget Practices: A Framework for Improved State and Local Government Budgeting’ (Online), (Retrieved April 11, 2012), http://www.gfoa.org/services/dfl/budget/RecommendedBudgetPractices.pdf

8. Government Integrated Financial Management Information System (GIFMIS) (2011), ‘Budgeting and Budget Management Reforms’ (Online), (Retrieved September 20, 2013), http://www.gifmis.gov.ng/gif-mis/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=6&Itemid=6#1

9. Kaufman, D. and Kraay, A. (2008), ‘Governance Indicators: Where Are We, Where Should We Be Going?’ Policy Research Working Paper No.4370 of the World Bank. (Retrieved September 21, 2013), http://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/pdf/wps4370.pdf

Google Scholar

10. Lienert, I. and Sarraf, F. (2001), ‘Systemic Weaknesses of Budget management in Anglophone Africa. International Monetary Fund’s Working Paper No WP/01/211.

Google Scholar

11. Lucien, P (2002), ‘Sound Budget Execution for Poverty Reduction’ World Bank Institute (Online), (Retrieved on November 12 2011) http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.201.4005&rep=rep1&type=pdf

12. Makinde, T. (2005) ‘Problems of Policy Implementation in Developing Nations: The Nigeria Experience’ Journal of Social Sciences, 11(1) 63-69.

Google Scholar

13. National Democratic Institution (NDI) (2003), ‘The Legislature and the Budget Process: An International Survey’ (Online), (Retrieved November 15, 2011), http://www.ndi.org/files/1651_gov_budget_093103.pdf

14. Nussle, J. (2012) ‘Perspectives on Budget Process Reform’, Journal of Public Budgeting & Finance, 32(3), 57-60.

Google Scholar

15. Obasanjo, O. (1999), ‘2000 Budget Speech: People’s Budget, presented by His Excellency President Olusegun Obasanjo at the Joint Session of the National Assembly. Abuja, November 24, 1999.

16. Olomola, A.S. (2009) ‘Strategies and Consequences of Budgetary Reforms in Nigeria’ Paper for Presentation at the 65th Annual Congress of the Institute of International Public Finance (IIPF), Cape Town, South Africa.

17. Omolehinwa, E.O. and Naiyeju, J.K. (2011) Theory and Practice of Government Accounting in Nigeria, Pumark Nigeria Limited, Lagos.

18. Otokiti, S.O. (2010) Contemporary Issues and Controversy in Research Methodology, Management Review Limited, Lagos

19. Pallant, J. (2011) SPSS Survival Manual: A Step by Step Guide to Data Analysis Using SPSS, Allen & Unwin, Australia

20. Pascua, L. (2005), ‘Operationalizing the MTEF in the Philippines: A Key to Reducing Poverty, Defining an Agenda for Poverty Reduction’ Proceedings of the first Asian and Pacific Forum in Poverty. Volume 1 pp. 138-144

21. State Partnership for Accountability, Responsiveness and Capability (SPARC), (2009), “Scoping the Introduction of Medium term Expenditure Framework in Nigeria State Government. (Online), (Retrieved September 21, 2013), http://www.sparc-nigeria.com/RC/files/2.1.6_MTEF_Scoping_Report_Discussion_Draft_26_Sept_2009.pdf

22. United Nations (2007), ‘Good Governance practices for the Protection of Human Rights’ (Online) (Retrieved on August 15, 2013), http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/GoodGovernance.pdf

23. World Bank (2001), ‘Honduras Public Expenditure Management for Poverty Reduction and Fiscal Sustainability: Latin America and the Caribbean Region’ Poverty Reduction and economic Sector Management Unit. Report No. 22070 (Retrieved on September 21, 2013), http://www-wds.worldbank.org/external/default/WDSContentServer/WDSP/IB/2001/08/29/000094946_0108070401001

/Rendered/PDF/multi0page.pdf.