Introduction

The terms of “technology parks”, “science parks”, “research parks”, “industrial parks” and “innovation parks”, etc. have always been used interchangeably in past studies (Chen and Huang, 2004; Pa’Imai, 2004; Vedovello, 2007). Generally, the terms refer to the clustering of industries designed to meet compatible demands of different companies within one location. The physical layout can be described as tract of land developed and subdivided into plots or zones according to a detailed plan equipped with roads, transport and public utilities for the use of a group of industrialists. Given the necessary support of infrastructure and facilities in the technology park, the companies expected to obtain benefit from economic scale. In addition, the comprehensive services provided will necessitate diversified effects on the surrounding region and finally, stimulate regional development. The technology park will basically act as the catalyst that drives the start-up of newly established high-tech firms, and guides the existing firms for advancement in process and product innovation. The broader roles of a technology park can be defined as:

i. Has formal and operational links with a university or other higher education institution or major centre of research

ii. Is designed to encourage the formation and growth of knowledge-based businesses and other organizations normally resident on site;

iii. Has a management function that is actively engaged in the transfer of technology and business skills to the organizations on site. (OECD, 1999).

Consequently, “Technology Park” in this study is defined as an area that allows benefits to individual firms located on the park (Chan and Lau, 2005). One of the critical benefits of technology parks is to encourage and facilitate the formation and growth of knowledge-based businesses, categorized as ‘incubator’. The incubator, therefore, will assist entrepreneurs with business start-ups and development, and with possible involvement of the public, private and non-profit sectors (OECD, 1999).

The development of Malaysia technology parks is closely related to the five-yearly programs of Malaysia Plan. In the Eight Malaysia Plan (2001-2005), the Malaysian Government was looking at the knowledge-economy as the basis of every spectrum of the nation’s development. This is continued further in the Ninth Malaysia Plan (2006-2010) and Malaysia’s Outline Perspective Plan (OPP 3, 2000-2010). Based on these plans, the government is continuing its effort to develop competitive and resilient SMEs that are equipped with strong technical and innovation capacity as well as managerial and business skills. In the recent Tenth Malaysia Plan (2011-2015), the government sets the stage for a major structural transformation that a high-income economy requires. The plan details strategies towards a more focused role for the government as a regulator and catalyst and programs that enable the country to emerge as a high income nation, as envisioned in Vision 2020. The foundation of any productive high income economy lies in a globally competitive, creative and innovative workforce. Hence, it requires an integrated approach to nurturing, attracting and retaining first world talent base (10th Malaysia Plan).

The increasing importance of high-technology industries in Malaysia, particularly in electrical and electronics industry led to the establishment of the first comprehensive high-technology park known as Kulim High-Technology Park (KHTP) in Kedah (Hasnan et. al, 2012). In the second half of the 1990’s, KHTP is expected to fulfill one of the strategies of the Seventh Plan that is to develop local electronic parts and components as well as to promote backward integration of the semiconductor industry through the establishment of wafer fabrication plants in order to minimize the dependence on imported components (Seventh Malaysia Plan, p.289).

Nevertheless, despite the significant role to the country development, there is still limited study focusing on the technology parks’ performance. In other words, there is still uncertainty about the tenants’ perception of the services that have been offered by the technology park. This paper, therefore, attempts to explore the impact technology park services have on high technology industries. A case study on one of the well-established technology parks in Malaysia that is Kulim Hi-Tech Park (KHTP) has been conducted.

Kulim Hi-Tech Park

KHTP situated in south Kedah, 40 kilometers from the island of Penang, Malaysia, offers 4,200 acres of development with a strategic location, support facilities, and human resources for high-tech manufacturing, and research and development (R&D) activities. As the first comprehensive high-technology park, Kulim Hi-Technology Park (KHTP) has created its own unique environment. If other high technology parks merely want to be a ‘technology free trade zone,’ conversely at the Kulim Hi-Tech Park, the companies aim to go beyond that and always try hard to ‘infuse’ technology into the day-to-day lives of the tenants and residents.

The increasing globalization, strategic alliances with overseas companies in capital intensive and high technology industries are vigorously promoted by the government. This significantly increases the role of KHTP in the Malaysian economy. Wafer fabrication is actually the main activity of KHTP. It is of strategic importance in the country’s industrialization drive as it is a core technology of the semiconductor industry. The establishment of wafer fabrication plants is expected to promote the development of high technology in Malaysia. The 1,700 hectare park targets technology-related industries, primarily in the fields of advanced electronics, telecommunications, biotechnology, advanced materials, research and development and emerging technologies.

Technology Park Services

The synergy between and among high tech firms can be generated through the structural elements provided by the incubator such as infrastructure and supporting facilities (Maillat, 1995; Phillimore, 1999). Generally, these services divided into basic structural support and technology-specific structural support. Common examples of basic structural support include shared office services, business assistance, rental breaks, business networking, access to capital, legal and accounting aid, and advice on management practices (Mian, 1997; Smilor, 1987; Harwit, 2002). Technology-related structural support features the following services: laboratory and workshop facilities (Mian, 1997), mainframe computers (Chan & Lau, 2005), research and development activities (Doutriaux, 1987), technology transfer programs (Smilor, 1987) and advice on intellectual property (OECD, 1999).

Although the number of technology parks and the research conducted on their performance is increasing, there is still uncertainty about whether technology parks are achieving their goals and what exactly their impact is on their tenants. The impact of differing institutional backers is still unknown. There is a gap in our knowledge about how an organization develops in the protected environment of a technology park (Hasnan et. al, 2010).

Strategy researchers have integrated the three organizational perspectives and developed performance measures in terms of multiple hierarchical constructs (Venkatraman and Ramanujam, 1986). The first is financial performance in terms of organizational effectiveness (Chakravarty, 1986). The second is organizational effectiveness measured by product quality and market share. Financial performance measures allow for competitive analysis where firms compare financial data regarding market share, sales, production costs or the budgets of competitors (Yasin, 2002).

Performance evaluation provides responses to questions such as, how and why an organization succeeds. These approaches work well when applied to the corporate environment where long terms data can be analyzed and compared with other organizations. However, the problems inherent in small firm research confront those attempting to apply these theoretical perspectives to research into incubators and their tenants (Remedios and Cornelius, 2003). On the other hand, non-financial operational performance measures have been used in small firm research (Murphy et al., 1996). Given that it is problematic to collect financial data from new ventures or small businesses, operational measures form a suitable base for building a framework for measuring the performance of start-ups located in incubators.

Mian (1997) proposed an integrated framework for the assessment of the performance of university technology incubator after reviewing and summarizing the salient features of four selected approaches to the incubator, i.e. goal approach, system resource approach, stakeholder approach and internal process approach. In this model, three sets of variables identified based on the related literature: (a) performance outcomes, (b) management policies and their effectiveness, and (c) services and their value-added. Lau and Chan (2005) modified the comparative evaluation approach to capture the effects on technology firms throughout the venture development path.

Based on the literature review, which discussed the purpose of the establishment of technology parks and the function of these incubation areas, it was found that several evaluation criteria can be utilized to determine the technology park performance from tenants’ perspective. They can be categorized as follows:-

a. Provide pooling resources (staff training, marketing event and exhibition)

b. Provide consulting/counselling services

c. Assist in reducing cost

d. Assist in funding.

e. Provide sharing resources (laboratory, testing equipment, meeting rooms, etc.)

f. Facilitate creating good image

g. Facilitate creating networking

h. Present advantages of clustering

i. Present advantages of geographical proximity

Methodology

A series of interviews have been conducted with representatives of Kulim Hi-Tech Park Corporation (KTPC) who act as the administrator of the plant. The interviews are very meaningful in order to understand the nature of operations, the involvement of stakeholders, technology park’s strategies, achievement and approaches defined via taking these competitive advantages. Based on the literature review and the conducted interviews, a set of close-ended questionnaires was developed to gather data on the nine evaluation criteria. The questionnaire contains a total of 40 questions that are divided into three sections. The two sections asked questions on the background details of the respondent and the firm, and the nine criteria of technology park performance.

The Sample and Data

The survey on the performance criteria involved a sample of industrial tenants operating in the technology park. The unit of analysis chosen is the company whereby the data were collected using survey method from the target respondents at the managerial level. These people were chosen because they are close to the decision- making involving the transfer of technology, and because they were involved in employee development. The sample size for this study was determined by using Krejcie and Morgan Table (1970).

There is a total of 53 companies operating in Kulim Hi-Tech Park. Therefore, a sample of 44 companies is needed in order to get the result that reflects the target population with 95 percent of confidence level, and a confidence interval of 5. By the use of simple random sampling procedure the questionnaires were distributed to the selected companies. However, only 32 completed questionnaires were received and given in 73 percent response rate. This response rate was quite reasonable compared to other studies on the tenants of technology parks, for example 35 percent (21 companies out of 60 companies) in Vedovello (1997). The data from the survey of this study can be analyzed with 95 percent of confidence level and with a wider confidence interval that is 18.

Results

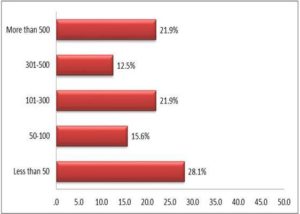

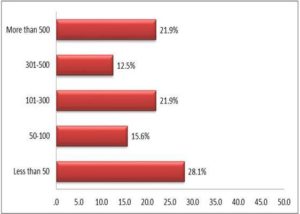

The respondents involved in this study are managers and directors or CEOs of the companies. 57.9 percent of the respondents have less than five years in their designations, 26.3 percent have between five to ten years, and three respondents have more than five years’ experience. The companies involved in the studies can be divided into three types of – local, multinational and joint-venture. The majority of the respondents (41%) are from multinational companies, followed by local (25%) and joint-venture (25%) while the others (9%) did not mention. In terms of company size from the employee perspective, 28.1 percent of the companies have less than 50 employees, while 21.9 percent have more than 500 employees. The breakdown of the number of employees in the companies is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Number of Employees

These companies are from various fields of high technology industries such as advanced electronics, semiconductors, wafer fabrication, biotechnology, mechanical electronics, industrial gases and services etc. The respondents were asked to rate the impact of the criteria on their companies with a scale ranged from zero to hundred. To study the impact of the technology services on the companies, the respondents were asked to indicate how long their organizations have been in the technology park. 42 percent of the companies have been less than 5 years in KHTP, 32 percent 11 to 20 years and 26 percent 5 to 10 years.

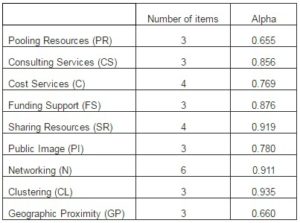

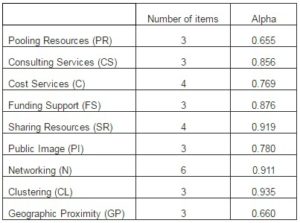

The mean score of each criterion is categorized into five groups as shown in very low, low, moderate, high and very high. Before further analysing the data, the consistencies of data have been tested to identify the consistencies of the variables. As show in Table 1, the alpha values of reliability analysis for this study range from 0.655 to 0.935. This signifies that misunderstanding is most unlikely to take place. From the results obtained, all the alpha values are greater than 0.6. Thus it can be concluded that this instrument has internal consistency and is therefore reliable.

Table 1: Reliability Analysis

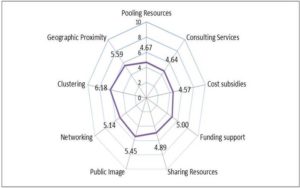

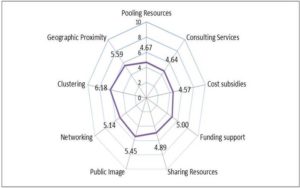

From the survey, it was identified that KHTP has all the evaluation criteria. However, the impacts of these criteria on the incubating companies are different. Figure 2 shows the illustration of the model for the existing impact of evaluation criteria on the incubating companies. It is found that the highest criterion is clustering. The overall mean score of this criterion is 6.1 or 61 percent actual rate. It can be considered as in high category. Besides, the other criteria are in moderate category. Those are graphical proximity (55.9% actual rate), public image (54.5% actual rate), sharing resources (48.9% actual rate), networking (51.4% actual rate), funding support (50% actual rate), consulting services (46.4% actual rate), pooling resources (45% actual rate) and cost subsidies (45.7% actual rate).

Figure 2: The Existing Evaluation Criteria in KHTP

Discussion

In general KHTP has all the evaluation criteria. It appears that the services provided by the technology park are able to contribute in the business development of the incubating companies. However, the results presented indicate that the impacts of technology park services in terms of the evaluation criteria are different. Among the criteria that obtain high score are clustering and geographic proximity. Apparently being located at KHTP provides the tenants with the advantage of obtaining services and supplies from well-established companies in this area. KHTP is well-connected, in terms of its road network as there is an expressway that provides easy access between KHTP to the North Butterworth Container Terminal (NBCT) seaport, North-South Expressway and to the Penang International Airport on the Penang Island, via the Penang Bridge. Being located at the high-tech park provides the companies with proximity to a good pool of readily available skilled and semi-skilled human resources for their operations. This really means that the work force around this location is accustomed to working in, as well as having sufficient knowledge and skills in, the technology industry.

On the other hand, in terms of pooling resources, funding supports and cost subsidies the technology park services have low impact on the tenant. These results obtained might be because of the services provided are depending on the size of the companies. Although one of the main criteria driving the decision to establish company in KHTP is the low cost of doing business with high technology facilities, certain services are only available for companies with certain criteria.

Conclusion

Kulim High Technology Park (KHTP) is developed to incorporate the most desirable characteristics of comprehensive and complete high-tech park. It is moving forward to be one of the best high-tech parks in the region. Nevertheless, to offer more value added to the tenant companies and to the nation as a whole, KHTP should always monitor its position and clearly understand the direction. Appropriate strategies and mechanism are needed to overcome the obstacles faced. A continuous program for assessing the dimensions of KHTP could be very important in order to identify the reasons and their challenges faced within the technology parks that led to an increase in the competitive capabilities.

Acknowledgment

The author is grateful to acknowledge the input from relevant Government and non-Government agencies such as Ministry of Higher Education (MOHE), Kulim Industrial Tenant Association (KITA), Research Management and Innovation Centre (RMIC) and their related associations.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

References

Chakravarthy, B. S. (1986). “Measuring Strategic Performance,” Strategic Management Journal, 7: 437-458

Publisher – Google Scholar

Chan, K. F. & Lau, T. (2005). “Assessing Technology Incubator Programs in the Science Park: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly,” Technovation, 25(2005), 1215-1228.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Chen, C.- J. & Huang, C.- C. (2004). “A Multiple Criteria Evaluation of High-Tech Industries for the Science-Based Industrial Park in Taiwan,” Information and Management, 41(2004), 839-851.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Cooper, A. C. (1985). “The Role of Incubator Organizations in the Founding of Growth-Oriented Firms,” Journal of Business Venturing 1, 75–86.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Department of Town and Country Planning, Peninsular Malaysia (DTCPM) (2010). ‘High Technology Industrial Park and Worker Housing,’ http://www.townplan.gov.my/english/guidelines_w.housing.php

Doutriaux, J. (1987). “Growth Pattern of Academic Entrepreneurial Firms,” Journal of Business Venturing 2, 285–297.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Harwit, E. (2002). ‘High-Technology Incubators: Fuel for China’s New Entrepreneurship?,’ China Business Review 29, 26–29.

Google Scholar

Hasnan, N., Abdullah, C. S., Osman, N. H., Mohtar, S. & Abidin, R. (2010). ‘The Development of Technology Park: An Overview’ Proc. The 5th Social Economic and Information Technology (SEiT) Seminar 2010, Hatyai,

Hasnan, N., Abdullah, C. S., Osman, N. H., Mohtar, S. & Abidin, R. (2012). ‘Malaysian Technology Park Development: Climbing the Ladder of Success,’ International Association of Management of Technology (IAMOT), Hsinchu, Taiwan

Hu, A. G. (2007). “Technology Parks and Regional Economic Growth in China,” Research Policy. 36 (2007), 76 – 87.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Jusoh, S. (2008). ‘Infrastructure and Development – Malaysia’s Experience,’ ATDF Journal, 4(4), 52-54.

Kulim Hi-Tech Park (2008). ‘ERP-Ready MSC Malaysia Cybercity,’ Techno tides Volume 1-2008

Kulim Hi-Park (KHTP): Ripe For Career Boost, Zahran.

http://www.khtp.my/news/kulim-hi-tech-park-ripe-for-career-boost.html#more-1028

Kulim Hi-Tech Park Jointly Plans Zambia’s Special Economic Zone http://thestar.com.my/news/story.asp?file=/2011/6/20/nation/20110620121325&sec=nation

Publisher

Lofsten, H. & Lindelof, P. (2003). ‘Science Parks and the Growth of New Technology-Based Firms-Academic-Industry Links, Innovation and Markets,’ Research Policy, 31(2002), 859-876

Maillat, D. (1995). “Territorial Dynamic, Innovative Milieus and Regional Policy,” Entrepreneurship and Regional Development 7, 157–165

Publisher – Google Scholar

Malaysia. (1996). ‘Seventh Malaysia Plan 1996-2000,’ Kuala Lumpur: Government Printers

Google Scholar

Malaysia. (1996). Third Outline Perspective Plan 2001-2010,’ Kuala Lumpur: Government Printers

Google Scholar

Malaysia. (2000). ‘Eight Malaysia Plan 2001-2005,’ Kuala Lumpur: Government Printers

Malaysia. (2006). ‘Ninth Malaysia Plan 2006-2010,’ Kuala Lumpur: Government Printers

Google Scholar

Malaysia. (2010). ‘Tenth Malaysia Plan 2011-2015,’ Kuala Lumpur: Government Printers

Google Scholar

Mian, S. A. (1997). “Assessing and Managing the University Technology Business Incubator: An Integrative Framework,” Journal of Business Venturing, 12, 251–285.

Publisher – Google Scholar

OECD (1999). Business Incubation- International Case Studies, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development Publications, Paris,

Publisher – Google Scholar

Palmai, Z. (2004). “An Innovation Park in Hungary: INNOTECH of the Budapest University of Technology and Economies,” Technovation, 24(2004), 421-432.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Phillimore, J. (1999). “Beyond the Linear View of Innovation in Science Parkevaluation: An Analysis of Western Australian Technology Park,” Technovation 19, 673–680.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Remedios, R. K. B. & Cornelius, B. (2003). ‘Cracks in the Egg: Improving Performance Measures in Business Incubator Research,’ Paper presented at the 16th Annual Conference of Small Enterprise Association of Australia and New Zealand, Ballarat, Australia.

Google Scholar

Robani, A. (2008). “Towards Successful Transformation into k-Economy: Assessing the Evaluation and Contributions of Techno-Science Parks in Malaysia,” The 5th Asialics International Conference 2008.

Publisher

Saffar, A. M. (2009). ‘Technology Incubation – Lesson Learn from Policy Makers and Stakeholders: What Works and What Does Not Work,’ Paper presented at the International Technology Incubation Forum, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Sanz, L. (2008). ‘Strategigram- A Tool to Deepen Our Understanding of Science Park Strategies,’ www.iasp.ws

“Science Park Powers a Solar System,” A Site Selection Investment Profile Kulim Hi-Tech Park, Malaysia From Site Selection magazine, November 2010 http://www.siteselection.com/issues/2010/nov/Kulim-IP.cfm

Publisher

Smilor, R. W. (1987). “Managing the Incubator System: Critical Success Factors to Accelerate New Company Development,” IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management 34, 146–155.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Tan, D. (2011). “Five MNCs in Negotiations to Invest in Kulim Hi-Tech Park,” The Star. thestar.com.my/news/story.asp?file=/2011/12/3/business/

Publisher

Vedovello, C. (1997). “Science Parks and University-Industry Interactions: Geographical Proximity between the Agents as a Driving Force,” Technovation 17, 491–502.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Venkatraman, N. & Ramanujam, V. (1986). “Measurement of Business Performance in Strategy Research: A Comparison of Approaches,” Academy of Management Review, 11: 801-814

Publisher – Google Scholar

Yasin, M. M. (2002). “The Theory and Practice of Benchmarking: Then and Now,” Benchmarking. An International Journal, 9(3): 217-243.

Publisher – Google Scholar