Introduction

In the meeting room Mr. Khaled Hashish, the CEO of Wadi Food, was sitting quietly before his team arrive thinking about the strategic options they have. Wadifood has been growing successfully ever since but now there is a serious doubt about the organic food market in Egypt. Four years ago, the Egyptian market seemed to be very promising. Consumers in Egypt were more and more influenced by the health concerns of the Europeans due to the high level of international exposure. The cleanliness of the soil of the Egyptian desert presented a perfect soil for organic production. The global increase in the fertilizers and pesticides prices increased the cost of conventional grown food and thus reduced the markup of organic food in the market. All these indicators led to seeing the Egyptian market with an enthusiastic eye. But now the situation has changed especially after the scandal of discovering non organic products being sold as organic right before the revolution. Consumers lost confidence in the organic food available in the market and the sales were dramatically diminished. The situation kept getting worse after the revolution and until this time the uncertainty faced is frightening. The production line of organic olives and olive oil seems to be recovering from the crisis; however, Mr. Khaled believes that the production line of fresh produce is not going quite well and he is not very optimistic about it. Questions like “should we invest more resources in the local market? Is the Egyptian market ready for organic food? What are consumers’ expectations after the revolution? Would they have more or less tendency to adapt healthier lifestyle?” were all over his mind.

Wadi Food

The story began with 30 hectares of olive groves…

30 hectares of olive groves planted 85 km south of Alexandria back in 1984 were the upshot of the Wadi Food in Egypt. The group’s huge success years before in Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, and KSA marked as the cornerstone to the existence of the now called Wadi Group producing annually 10,000 MT of pickled olives and 1000 MT of olive oil for the local and international market. Wadi Food was an aspiring inkling fueled by an ambition of supplying the world with natural and healthy products free of any human meddling. This passion and commitment were the force by which Wadi Food reached its current esteemed status offering more than 100 products packaged in a variety of containers.

Wadi Group’s umbrella includes a number of companies with one unified goal of producing and delivering nothing but high quality products to consumers and businesses. 2010 marks the Wadi Group’s silver jubilee. Some of the group’s affiliates operating in 3 different divisions of: Poultry, Agro-Food & Industry are currently undergoing multiple corporate restructuring. So far, the results of the aforementioned restructure are the risings of 2 new sectors: Mazareh (Farms) and Sina’at (Industries). Both of the Poultry and Agro-Food divisions are grouped under Mazareh of which 2 main key B2B companies “Katkoot al Wadi” & “A’laf al Wadi” operate, as well as 2 B2C ones “Wadi Food and Wadi Farms”. Whilst “Sina’at” sector comprises Wadi Group’s industrial subsidiaries; Wadi Glass (called now Zugag), Tabreed, & other industrial projects like Idafat, Asmida & Tawseel (still under development).

Wadi’s achievements over the years have been made possible by the committed, diligent, and ambitious workforce of the group. The commitment and the “no compromises for quality” attitude is what made it even possible to believe that the current investments and turnover’s numbers will sky-rocket once the new projects are finalized. Its Vision is “To be one of the most respected & inspiring corporations, leading & excelling in every business we operate” and its Mission is “To grow our core businesses to their full potential in poultry, agriculture & industry and develop new opportunities leveraging our expertise and resources with uncompromising dedication to efficiency, innovation, quality, service, and talent development.”

The investments diversification idea started playing around in Wadi leadership’s heads five years into the success story. It started with olive plantations which now covers over 5,000 acres. Olive processing and olive oil production followed and the facilities have earned various certificates of food safety and organic status. Today, Wadi Food has become a household name in Egypt, and extending over to a large number of Arab Gulf States, Canada, USA, and Europe.

Stating facts and numbers from the past can only be an insight into the future, in which they take the promise upon themselves to continue to lead and grow in the agriculture and food division. They promise to reach out to cover thousands and thousands of acres; they promise to plant quality olives, grapes, tomatoes and organic vegetables. They promise to keep meeting and exceeding your expectations .

Organic Food Market

Environmental issues have become one of the most highlighted topics in today’s global market. Consumers’ concerns about the environment started boosting from the late 1980s in Europe while it has been drawing the US consumers’ attention earlier since the 1960s. Environmentalism has been growing ever since with the last decade being called “the decade of the environment”. Now environmentalism has become one of the most significant competitive edges to stay in the market (Fotopoulos and Krystallis, 2002a; Krystallis and Chryssohoidis, 2005). Currently, environmental issues are said to affect consumers’ spending and shopping behavior, thus the identification of green consumers has turned to be a vital task especially for the retail industries (Davies et al., 1995).

Consumers with high environmental concerns are usually participating in activities to support their environment such as recycling of paper and glass. However, purchasing organic products has become a widely accepted way by which consumers’ concerns about the environment are reflected (Chakrabarti, 2010). In other words, the purchase of organic food has become a projection of environmental and health conscious consumers in the market (Krystallis and Chryssohoidis, 2005).

A consistent annual growth of organic farming has been noted to be around 25% in EU and US during the 1990s, consequently the value of organic markets has been increasing ever since (Krystallis and Chryssohoidis, 2005). The global organic market has been reported to be worth US $40 billion in 2006 with the largest share of organic products being marketed in Europe and North America (Xie et al., 2011). From a small to a booming market, the organic sector has impressively grown in the past 15 years. For instance, a total increase in demand by 18.1 is reported in France between the year 2005 and 2009, whereas in Germany and Italy the demand has increased by 8.7 percent and 11.9 percent respectively from 2000 to 2008 . Such growth of organic markets not only affected the developed countries but also the developing as well. The global increase in demand for organic products has created an opportunity for developing countries to increase their exports but only if they have the know-how to produce such products at high quality standards.

Egypt is one of the developing countries that were capable to convert such opportunity into reality. Industrial Modernization Center published that according to Egypt’s Food Sector Export Strategy 2006, the estimated value of organic food exports for the year 2004/2005 was 12,326 tons including organic vegetables, fruits, pharmaceutical plants, herbs and spices and olive oil . In addition, in the last three years, an annual growth of 30 percent in agricultural exports is reported where almost 60 percent are exported to European countries. Germany and Italy are said to be ranking first on the Egyptian organic food and herbs export list 2.

Although the exports are high, the local market continues to be very small due to the poor level of awareness with regards to health and nutrition issues. Yet, there is a number of initiatives taking place in the market to support and develop the organic market in Egypt. For instance, the Fayoum Agro-Organic Development Association (FAODA) provides farms which are willing to convert from conventional agriculture to organic one with the essential training and support to become certified organic farms. Through the five years journey of training Egyptian framers in Fayoum, 1800 men and women received extensive training while ensuring their compliance with the standards of the International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements 2. Other initiatives are more concerned with regulating the organic market such as the Antitrust Authority and Organic Products Association which persistently calls for setting high local standards and ensuring the existence of effective inspective firms to protect local consumers .

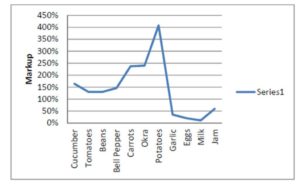

Different types of organic food are available in the market including fresh produce, dairy, jam, juice and herbs. The fresh produce included only vegetables with limited variety offered including cucumber, tomatoes, potatoes, okra, bell pepper, beans, egg plants, garlic and onions. As for the price of organic food, the mark up ranges from 16% to 350% depending on the type of food and its country of origin (see Exhibit 1).

Figure 1: Markups of organic products compared to conventional products

Source: Developed by the researcher in an observational study conducted in 2008

The Organic Food Consumer

It is important to know exactly the consumers of organic food in order to effectively understand and serve their needs. Knowing who exactly buys organic food in a given market can provide essential insights into segmenting the market. Not only would it help in knowing which segments could be efficiently served, but also in identifying which segments are the most profitable. Purchasing organic food reflects a life style decision made by consumers who have high environmental consciousness (Fotopoulos and Krystallis, 2002b). Generally speaking, not all people declaring to have environmental concerns act accordingly and purchase organic food, those people are known as the “arm chair” greens. While those who take a positive step and act are divided into two other groups: the dark greens and the light or pale greens. Dark greens are keener to look for green products unlike the light greens consumers who purchase organic food in a more impulsive way and tend to have higher price sensitivity (Davies et al., 1995)

In many countries, young women with children having high levels of education and income are believed to be the most frequent buyers of organic food (e.g. Davies et al., 1995; Krystallis and Chryssohoidis, 2005). Moreover, people falling in older age groups ranging from 55 to 60 years old are said to be another important group of regular organic food purchasers, as they are more vulnerable to health hazards and thus their purchasing decisions are affected by their health concerns (Ankomah and Yiridoe, 2006). Health and safety concerns are believed to be the most significant motivations for purchasing organic food (Klockner and Ohms, 2009). Other motives are associated with superior taste, animal welfare and consumers’ willingness to support organic farmers (Haper and Makatouni, 2002; Pellegrini and Farinello, 2009)

It is not necessarily true that the act of not buying a certain product reflects peoples’ disinterest in the product. Purchase as a signal for peoples’ interest in a particular product undermines the importance of responding to consumers’ dissatisfaction and understanding their continuous need for change. In other words, it underestimates the significance of determining the possible barriers of buying such products which consumers might have interest in. Thus, realizing these barriers might help in the process of expanding specific markets, specially immature or undeveloped ones. Talking about organic food, some barriers are found to be related to the organic food itself, while others are found to be related to consumers’ decision making. Examples of barriers related to organic food are premium prices, low availability and problems related to advertising and labeling organic food (Klockner and Ohms, 2009; Torjusen et al., 2004). Price and availability are known to be the most common barriers (e.g. Bryne et al., 1992; Davies et al., 1995; Fotopoulos and Krystallis, 2002a; Lea and Worsley, 2005; Krystallis and Chryssohoidis, 2005), however, it is argued that there is a shift in the importance attributed to these two barriers while the consumer transfer from the initial acceptance phases to latter stages of maturity and consciousness. At the early stages of consumer’s acceptance, price is the factor that most likely hinder consumer purchase, while as the market becomes more mature consumer’s sensitivity to high prices decrease and thus availability become a stronger factor that hinder consumer purchase of organic food (Fotopoulos and Krystallis, 2002b).

At a general level, the majority of consumers are willing to bear a premium level ranging from 10% to 20% at most. However, considerably higher –as high as 100%- premium levels are recorded across countries when more specific organic food markets are analyzed (Ankomah and Yiridoe, 2006). Similar to the law of demand, the percentage of consumers willing to pay diminishes as the markup rises. In other words, consumer’s willingness to pay is directly related to the concept of price elasticity of demand, meaning that there are high adverse effects on consumer’s purchases when price premium rises (Piyasiri and Ariyawardana, 2002).

Several claims aimed to justify the reasons behind the high prices of organic food. Factors like the higher production cost especially during the conversion period (Davies et al., 1995) and lower yield from organic produce compared to conventional produce force the producers to raise the price in order to achieve the desired level of profitability (Fotopoulos and Krystallis, 2002; Rehber and Turhan, 2002). It is often argued that explaining the reasons behind the higher price of organic food and trying to reinforce the perception of organic food as a value of money choice can lead to the possibility of reducing the importance attributed to price as a barrier (Padel and Foster, 2005). As for barriers related to consumers’ decision making, examples found are related to trust and information risk issues (Torjusen et al., 2004).

Decision Time

Mr. Khaled and his team are now studying the alternative courses of action for the current situation. Not too many options seem to be available in the time being. Mr. Khaled has gathered his team specifically to discuss the opportunity to convert two out of the three organic farms they have into conventional farms.

“It is becoming more and more difficult to compete in the international market and local market is just not so ready. Conventional farming yields in much higher productivity than organic farming. Besides, the prices of conventionally grown fresh produce are skyrocketing. We will downsize our organic production of fresh produce and continue selling organic fresh produce but only in our outlets” said Mr. Khaled.

Mr. Tarek Yasser, the marketing director, could not agree more. This industry is predominantly susceptible to political instability and economic crisis. There is a severe ambiguity about the political situation in the country. It might take just few months for the situation to resolve till the presidential elections or it might take years. “Let us not rush this decision and wait for a couple of the months till the presidential elections end” said Mr. Hazma Ziad, the operation manager. If the political situation stabilized, I believe there will be a great potential in the Egyptian market. After the revolution, consumers became more aware of their rights, they were proven to be political conscious citizens and with little effort from various stakeholders they would become more health and environmental conscious. In the last few months in Mubarak’s regime, it was announced that the Agriculture ministry was working on a new law to organize the circulation of organic agricultural products to be reviewed by the cabinet and the parliament to ensure organic agricultural standards are applied . I believe the new ministry with cooperation of the new parliament will set plans which provide a detailed framework, deter policies, and measures in order to ensure that organic farming methods are followed. This means not only we would anticipate different types of consumers, but also fewer and different players in the market.

The Fruit Logistica 2012 conference in Berlin is approaching. I guess by then we will have a clearer picture of the international market demands, said Mr. Khaled. Whether to convert the organic farms into conventional farms remains an unanswered question that needs extensive study and research to be answered.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

Reference

1. Ankomah, S.B., Yiridoe, E.K. (2006), ‘Organic and conventional food: A literature review of the economics of consumer perceptions and preferences. Final report submitted to Organic Agriculture Centre of Canada’ [Retrieved on 14 November 2007], http://www.agmrc.org/NR/rdonlyres/7E976A20-4B28-4657-995E-8FD3BD80DD71/0/litreview. pdf

Google Scholar

2. Chakrabarti, S. (2010), ‘Factors influencing organic food purchase in India – expert survey insights,’ British Food Journal, 112 (8), 902-915

Publisher – Google Scholar

3. Davies, A., Titterington, AJ., and Cochrane, C. (1995), ‘Who buys organic food? A profile of the purchasers of organic food in Northern Ireland,’ British Food Journal, 97 (10), 17-23

Publisher – Google Scholar

4. Fotopoulos, C. and Krystallis, A. (2002a), ‘Purchasing motives and profile of the Greek Organic consumer: A countrywide survey,’ British Food Journal, 104 (9), 730-765

Publisher – Google Scholar

5. Fotopoulos, C. and Krystallis, A. (2002b), ‘Organic product avoidance: Reasons for rejection and potential buyers’ identification in a countrywide survey,’ British Food Journal, 104 (3/4/5), 233-260

Google Scholar

6. Harper, GC. and Makatouni, A. (2002), ‘Consumer perception of organic food production and animal welfare,’ British Food Journal, 104 (3/4/5), 287-299

Publisher – Google Scholar

7. Klockner, CA. and Ohms, S. (2009), ‘The importance of personal norms for purchasing organic milk,’ British Food Journal, 111 (11), 1173-1187

Publisher – Google Scholar

8. Krystallis, A. and Chryssohoidis, G. (2005), ‘Consumers’ willingness to pay for organic food: Factors that affect it and the variation per organic type,’ British Food Journal, 107 (5), 320-343

Publisher – Google Scholar

9. Padel, S. and Foster, C. (2005), ‘Exploring the gap between attitudes and behavior: Understanding why consumers buy and do not buy organic food,’ British Food Journal, 107 (8), 606-625

Publisher – Google Scholar

10. Pellegrini, G. and Farinello, F. (2009), ‘Organic consumers and new lifestyles: An Italian country survey on consumption patterns,’ British Food Journal, Vol. 111 (9), 948-97

Publisher – Google Scholar

11. Piyasiri, AG. and Ariyawardana, A. (2002), ‘Market Potentials and Willingness to Pay for Selected Organic Vegetables in Kandy,’ Sri Lankan Journal of Agricultural Economics, 4, (1), 107-119

Google Scholar

12. Rehber, E. and Turhan, S. (2002), ‘Prospects and challenges for developing countries in trade and production of organic food and fibers: The case of Turkey,’ British Food Journal, Vol.104 (3/4/5), 371-390

Publisher – Google Scholar

13. Torjusen, H., Sangstad, L., Jensen, K.O. and Kjaernes, U. (2004), ‘European consumers’ conception of organic food: A review of available research’ Professional report no.4 for the National Institute for consumer Research. [Retrieved on 14 November], http:// www.organichaccp.org/haccp_rapport.pdf

Google Scholar

14. Xie, B., Tingyou, L. and Yi, Q. (2011), ‘Organic certification and the market: organic exports from and imports to China,’ British Food Journal, 113 (10), 1200-1216

Publisher – Google Scholar