Introduction

The contemporary manager engages in basic aspects of executive work that involves undertaking tasks associated with planning, organising, leading and controlling (Campling et al., 2008). Indeed, Wren and Bedeian (2009) indicate that the majority of textbooks dealing with management science invariably explain executive roles, concepts and organisational practices from the perspective of these four fundamental managerial functions. Ordinarily within any organisational environment, managers can expect to engage in a spectrum of activities that might be grouped under each of these four areas (Campling et al., 2008; Robbins et al., 2009)— making their position more cohesive, inclusive and ultimately more rewarding.

Within the realms of modern day executive work, the chief information officer (CIO) position is relatively new when compared to the other high level executive roles such as the chief executive officer and chief financial officer. Notably, the CIO position emerged around the early 1980s where organisational information technology (IT) became an important driving force in allowing a firm to achieve competitive advantage (Banker et al. 2011). The CIO provided the important link between a firm’s IT applications and the high level executive management (Hunter 2011). Today, the CIO role is seen as falling under the “Chief” or “C” suite of executives, with the individual occupying this position being responsible for the alignment of the firm’s business performance with implemented information and communication technology (ICT) capabilities (ICIS 2008). Various CIO studies have been undertaken and report the CIO as a leader that engages with top-level management (Grover, 1993; Broadbent and Kitzis, 2005; Sojer et al., 2006; Hunter, 2007; Currier, 2009; Waller et al., 2010) and how the CIO performs within the organisational setting (CISR-July, 2005; Smaltz et al., 2006). Some studies have postulated on the CIO role and how it might look in the future (Broadbent and Kitzis, 2005; ICIS, 2008; CISR-January, 2009; Currier, 2009; Waller et al., 2010). Given the importance of this organisational role, the activities of the CIO have not been clearly articulated from an executive viewpoint reflecting the four functional areas of management; thus providing the underpinning motivation for this research. Arguably, the mapping of CIO activities to these management functions would clearly articulate a greater understanding of the position and some of the challenges it presents.

Literature Review

Work activities undertaken by executive managers can be associated with the areas planning, organising, leading or controlling (Campling et al., 2008)— commonly known as the fundamental areas under which management activities are performed. These work areas or functions are premised on the seminal work of French industrialist Henri Fayol, who identified the key elements and principles of management last century (Parker and Ritson, 2005). The work of Fayol is recognised as documenting the top-down activities of what managers do in order to carry out organisational objectives (Robbins et al., 2009). The importance of Fayol’s work is re-iterated by Wren and Bedeian (2009) who indicate that most textbooks dealing with contemporary management are underpinned by various concepts and theories that are explained within the scope of these four management functions. The breakdown of executive activities into these functions areas is not just applicable to people working in large firms; Mukerji (2000) indicated that the small business operator will invariably undertake daily procedures that also have a planning, organizing, leading or controlling focus.

Schermerhorn (2008) also re-iterates that regardless of a manager’s organisational setting, their responsibilities and activities will invariably fall under these four functional areas. Moreover, the activities that fall under each of these areas are not carried out in a sequential manner— managers tending to multi-task activities to achieve organisation goals (Campling et al. 2008). Bartol and colleagues (2008) proposed that the four management functions have a degree of interconnectivity and that the organisation’s operating environment potential can shape and influence how activities are undertaken. Indeed, a manager’s activities are potentially shaped by a firm’s operational environment— allowing actions to be directly applicable to customers and suppliers, and in some instances directly associated with competitors. Furthermore, many organisations operate within formal and informal political and social frameworks— thus potentially dictating the activities a manager might undertake in relation to local and global objectives (Bartol et al., 2008; Campling et al., 2008; Schermerhorn, 2008; Williams and McWilliams, 2010). A salient description of the expected activities associated with each of the four functional management areas now follows.

Planning Activities Associated Management

The activities associated with the management function of planning relate to addressing the organisation’s mission, core values, strategies and objectives (Campling et al., 2008; Robbins et al., 2009)— activities that recognise the business drivers in aligning the business with current and future environment. Planning as a function embraces actions associated with the decision-making process that allows the manager to determine the appropriate actions required to achieve organisational aims or goals. Moreover, planning is a vitally important activity that supports innovation that will reflect future organisational strategic development as well as competitive aims (Schermerhorn, 2008; Williams and McWilliams, 2010). Planning can be affiliated with long and short term organisational goals across the spectrum of interdepartmental and hierarchical levels that exist in the company. Indeed, planning initiatives need to anticipate and accommodate organisational change. Planning might also involve scenario planning and problem solving activities allowing a manager to experiment with various ‘what if’ situations in order to determine how corporate objectives might be accomplished (Bartol et al., 2008).

Organising Activities Associated Management

The activities associated with the management function of organising include the co-ordination of tasks, people and organisational resources (Bartol et al., 2008)— in essence the manager’s focus involves the creation of the relevant structures within an organisation so as to be able to accomplish the identified and postulated organisational objectives. Organising allows managers to meet planning objectives and strategies by supporting staff with resources such as current technology, access to relevant human resources skills and by formulating appropriate team-orientated facilities (Campling et al., 2008; Schermerhorn, 2008; Robbins et al., 2009). Management organising activities can be generally viewed as embracing implementation tasks that are supported by appropriate resources commensurate with corporate planning directives. Such support will reflect a financial costing activity that is associated with this organising function. Implicit in the activities associated with the organising is the co-ordination of people and their on-going skills acquisition through training, knowledge acquisition and development (Schermerhorn, 2008; Williams and McWilliams, 2010).

Leading Activities Associated Management

The activities associated with the management function of leading embraces tasks that are individualist and are associated with communicating, support for the organisational vision, promoting organisational goals and inspiring/motivating people to perform at a high level (Schermerhorn, 2008). Successful leadership approaches are varied and might focus on building people relationships, team development or promoting organisational and operational efficiencies. Leading activities can be associated with engendering enthusiasm amongst people, making a compelling and clear case for the firm’s future direction and engaging organisational stakeholders (Bartol et al., 2008; Campling et al., 2008; Schermerhorn, 2008). Other leading activities lend themselves to a team orientation and focus, being shaped by either formal or informal organisational interaction. Furthermore, executive leading activities can reflect active processes that allows the individual to champion various aspects of organisational transformation, promoting innovation, motivating people and communicating the organisational message (Bartol et al., 2008; Robbins et al., 2009; Williams and McWilliams, 2010).

Controlling Activities Associated Management

The activities associated with the management function of controlling include activities that relate to measuring performance and ensure that the desired results are attained (Campling et al., 2008; Robbins et al., 2009). The control process involves establishing and measuring performance objectives and standards, and comparing outcomes such as industry norms and quality so as to make appropriate adjustments to organisational processes. Controlling invariably ensues that performance targets are met and that the outcomes are aligned with the goals formulated as part of the original management planning phase. Controlling activities can embody tasks that have a maintenance and regulatory focus so as to ensure that organisational performance adheres to previously identified goals, as well as industry benchmarks (Schermerhorn, 2008).

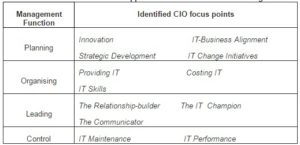

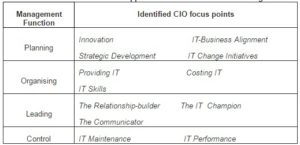

Table 1 provides a summary of the noted activities associated with each of the four management areas of planning, organising, leading and controlling that have been noted as tasks that an executive manager can undertake (groupings of activities are based on the notable aspects encountered under each section from the preceding literature).

Table 1: Identified Activities Associated with Each of the Management Functions

A Primer on the Role of the Chief Information Officer

The CIO position was created in the early 1980s as a result of a firm’s recognition of the rising importance of IT as a means to improve organisational performance (Hunter, 2011). Indeed, the introduction of newly applied information technologies in recent times have had an impact on the CIO position and have transformed the dynamics of the role (Smaltz et al., 2006)— developments that will further elevate the importance of the CIO role. Moreover, an important role of the CIO is to shape organisational expectations with respect to IT— with expectation directly reflecting aspects of the firm’s business mission, economic outlook and whether the company is focused on growth or industry consolidation. Consequently, the skills required by a CIO can be expected to be diverse, adaptable and also reflect the demands of the business cycle at a specific point in time (Head, 2008). Head further notes that CIO activities are multifaceted and include the ability of the incumbent to manage and deal with organisational stakeholders, to continually champion and reinforce the case for IT adoption as well as to demonstrate the alignment of technology with business requirements. Competencies associated with the CIO role were examined by Tagliavini et al. (2004) using a set of dimensions that were deemed as ‘know how to be’, ‘ know what’ and ‘know how’ dimensions. CIO competences associated with the ‘know how to be’ dimension reflected an individual’s behavioural traits that embrace qualities such as being able to have a long-term organisational vision, a propensity to be innovative and the procession of interpersonal attributes associated with communication and relationship building. Lane and Koronios (2007) also examined the competencies of the modern CIO reporting that some of the highly rated skills directly related to activities that allowed CIOs to successfully engage in strategic IT business planning, aligning business innovation with IT capabilities and understanding IT corporate governance. Smaltz et al. (2006) proposed that the CIO executive fulfilled a myriad of potential roles that allowed him/her to take on activities related to being a strategist, a systems integrator, the relationship between an architect, an educator, an IT provider and one stewarding the value of information. The strategic skills required the CIO to be able to shape the organisational strategic plan as well as the firm’s mission/vision by providing expertise on the value of IT to the firm. Systems integration activities addressed the development/acquisition of computer-based systems as well as those that dealt with the integration of enterprise-wide applications. The CIO, as a relationship architect, focused on interacting with external service providers as well as being able to engage the organisation’s non-IT personnel. As an educator, the CIO championed various aspects of computer literacy throughout the organisation, as well as being in the position to inform top management teams (TMT) on nascent technologies. The CIO as an information steward, acted in a position that allowed him/her to maintain the integrity of organisational information by addressing issues related to data security, quality, confidentiality and staff IT skills. The CIO as an IT utilities provider, allowed the person to manage and establish a responsive IT department.

Some researchers report that CIO activities embody tasks that are associated with the provision of quality and cost-effective IT services, the management of technology outsourcing, facilitating important departmental computer operations such as human resources (HR) and financial services. Furthermore, CIOs have been noted to allocate their time across several areas that include providing the organisation’s IT service, interacting and engaging with non-IT personnel, addressing customer requirements and being aware of enterprise processes (CISR-July, 2005; CISR-March, 2008; CISR-January, 2009). Chun and Mooney (2009) examined the CIO role and suggested the position addressed various aspects of aligning the company’s business strategy with supporting corporate IT infrastructure. They identify a range of CIO activities with the most significant addressing issues such as:

- Having the ability to contribute to corporate strategy,

- Being able to address innovation and organisation needs,

- Promoting IT within the company,

- Being an effective communicator and negotiator,

- Having competencies that allowed him/her to exhibit expertise in the area of IT costing and impacts, and

- Being able to anticipate and address change (facilitated by problem solving & decision making abilities).

The CIO role has various dimensions associated with numerous responsibilities that can influence decision-making and contribute to informing the senior management level of the company (Weill and Ross, 2004). Moreover, CIO responsibilities can directly reflect various activities associated with the costing of organisational technology in general, as well as the delivery of IT service, managing business processes as well as understanding the firm’s IT business value. Weill and Ross (2004) also propose a set of assessment factors that document CIO skills, such as leadership, collaboration and teamwork— skills that are associated with directly improving organisational IT business value. Another study that examined the Portuguese CIOs found that relevant activities are associated with the CIO having understanding business processes; being able to communicate effectively; possessing strategic planning acumen and having technical proficiency with respect to IT related issues (Trigo et al., 2009).

Hunter (2007) documented the experiences of CIOs and concluded that the role embodied important facets of knowledge and leadership which allowed them to guide the firm in the adoption and use of computer technology. Furthermore, well-defined activities associated with the CIO position had either user or technology focus. In the user-centric position, CIO interaction with users was premised on how technology might impact on them and the resultant change management and/or resistance to change issues that might arise. CIOs that had a techno-centric focus undertook distinctive activities that dealt with technology investments— reflecting how they considered and evaluated existing or future IT requirements. Hunter (Hunter 2007) further identified a set of CIO activities, noting responsibilities associated with appropriate/relevant IT staff training, an awareness of performance standards affiliated with IT service delivery, IT leadership and well-informed ideas with respect to the potential benefits of emerging technologies.

Important tasks performed by CIOs have been identified in the key areas of strategy, infrastructure and initiatives, as well as managing the IT department (Currier, 2009). Some of the important CIO skills identified across each of these key areas include the ability to deal with how corporate strategy is aligned with IT requirements, using firm-based information strategically; leading enterprise-wide IT-related initiatives and overseeing the management of IT projects. Li et al. (2006) investigated the personality traits of CIOs in order to better understand IT management practices by firms. CIO communication characteristics such as being open and extroverted were noted as important facilitators to shaping innovative applications of technology by a business. CIO challenges and prospects associated with the CIO have been documented to reflect various activities and skills that allow him/her to (ICIS 2008):

- Ensure that organisational IT systems are cost effective,

- Engage in innovative practices in order to exploit new and improved IT systems and

- Oversee the daily interaction between an organisation’s IT systems and its business people.

Weill and Ross (2009) allude to the CIO being able to undertake activities that potentially are aligned with running IT operations as well as being able to work with business leaders. Such activities also include being able to ensure stakeholder buy-in to various technology projects and the championing of shared organisational IT services and applications. Banker et al. (2011) report that CIOs assume an influential position to oversee the firm’s IT function. They note important CIO activities that include the overseeing of business information resources, providing a vision for the utilisation of IT by the firm and articulating the value of IT as a vehicle for organisational change. Sojer et al. (2006) indicate that CIO activities can be mapped to upstream (demand-sided) and downstream (supply-sided) tasks. Upstream tasks focused on aspects of organisational responsiveness to the external environment, whilst downstream tasks tended to be internally focused, reflecting operational issues. The investigators proposed different CIO tasks to reflect his or her role as a supporter, enabler, project manager or driver. These CIO descriptors denote the importance the firm placed on the value of information technology— be it from an operational (internal) or strategic (external) perspective. Sojer et al. (2006) propose that the CIO in the supporter role has activities that are primarily responsible for the provision of operational IT— the company with a CIO in this support role has little or no value in using IT strategically. The CIO in the driver role reflects a situation where a firm values their IT highly, both at the operational level as well as from a strategic perspective. The CIO as an enabler focuses on the strategic use of IT to address a firm’s operational requirements, with externally-focused IT applications being a low priority. The CIO described as a project manager has an important role for a company that has future aspirations to strategically adopt new IT— the CIO in this instance acting either as an implementer of this IT or in a cost-cutting role.

From the contemporary literature associated with the CIO position, a number of important activities can be noted. The next section of the paper maps these noted CIO activities to the four management functions.

CIO Activities Segmented to the Executive Management Functions

Many of the CIO studies that were examined in the previous section have highlighted various activity areas that reflect practices of the modern-day CIO. As an executive manager, CIO activities can be segmented into the primary functions of planning, organising, leading and controlling based on the attributes (Sellitto, 2010) with the group headings of Table 1 being modified to reflect an information technology focus of the CIO activities. These groupings of CIO activities into the four management functions designated the CIO focus points and are summarised in Table 2. A description of each function’s activities and associated activity subsequently follows.

Table 2: Noted CIO Activities Mapped to the Four Functions of Management

The Planning Activities of the CIO

Planning activities tend to relate to how the CIO as an executive might address the organisation’s mission, core values, strategies and objectives. Moreover, planning is a vitally important activity that supports innovation so as to support organisational strategic aims. The identified CIO position activities associated with planning include:

- Innovation: This planning activity is directly reflected by activities that allow the CIO to exploit nascent, new or emerging technologies so as to allow the organisation to address business needs (Smaltz et al., 2006; Hunter, 2007; Chun and Mooney, 2009).

- IT-Business Alignment: Elements of this CIO planning activity focused on how the CIO might examine the importance, and subsequent alignment, of IT with respect to the corporate objectives, business requirements and long term vision (Tagliavini et al., 2004; Hunter, 2007; Lane and Koronios, 2007; Head, 2008; Currier, 2009; Banker et al., 2011).

- Strategic Development: The CIO has been reported as having a strategic role or focus at an organisational level where he or she might shape, contribute and assist in formulating the over-arching organisational IT strategy (Smaltz et al., 2006; Chun and Mooney, 2009; Trigo et al., 2009).

- IT-Change Initiatives: CIOs need to be aware of the dynamics commonly encountered as the organisation evolves and changes. Hence, CIO activities associated with planning invariably will deal with IT change management and resistance to change issues (Hunter, 2007; Chun and Mooney, 2009; Currier, 2009; Banker et al., 2011).

The Organising Activities of the CIO

Organising activities are associated with the co-ordination of tasks, people and resources that allow a manager to structure and facilitate an appropriate environment so as to address organisational goals. The identified CIO position activities associated with organising include:

- Providing IT: The provision of core technological applications and IT services is a reported activity of the contemporary CIO. Such activities can centre on the provision of operational IT (CISR-July 2005; Sojer et al., 2006; CISR-March 2008; CISR-January 2009), appropriate IT service delivery (Weill and Ross, 2004) and the development, acquisition and use of IT within the organisation (Smaltz et al., 2006; Hunter, 2007). IT outsourcing also falls under this domain (CISR-July 2005; CISR-March 2008; CISR-January 2009).

- IT Skills: Skilled personnel are an important element associated with the delivery of organisational IT services. Organising activities associated with IT staffing requirements are an integral component of the CIO position (Smaltz et al., 2006; Hunter, 2007).

- Costing IT: Part of the organising activities of the CIO is associated with the financial value of IT-related resources. Indeed, this organising activity directly relates to the CIO being able to deliver cost effective IT service (CISR-July 2005; CISR-March 2008; ICIS, 2008; CISR-January 2009). Another CIO organising activity might also embrace aspects of project management which will potentially have a cost-cutting focus (Sojer et al., 2006).

The Leading Activities of the CIO

Leading activities embrace tasks that are associated with communicating the organisational vision, building people relationships, engaging in team work and making a compelling and clear case for incorporating IT in the firm’s future strategy. The identified CIO position activities associated with leading include:

- The relationship-builder: The CIO activities associated with this aspect of leading directly relates to how the CIO engages and addresses his or her non-IT organisational peers (Smaltz et al., 2006; CISR-January 2009). The engagement of non-IT peers can be:

- At the stakeholder level ensuring important buy-in for IT projects (Head, 2008; Weill and Ross, 2009),

- At senior management level where the CIO might influence and contribute to IT related decision-making (Weill and Ross, 2004; Waller et al., 2010),

- By directly working with other organisational business team leaders (Weill and Ross, 2009),

- Interaction with external entities such as customers (CISR-January 2009) and service providers (Smaltz et al., 2006).

- The IT Champion: An important element of leading-focused activities is how the CIO might champion the organisational case for IT (Head, 2008) as well as the implemented or proposed IT services and applications (Weill and Ross, 2009). As an IT champion, the CIO will embrace an information dissemination function within the firm (Chun and Mooney, 2009).

- The Communicator: Underpinning the leading activities of the CIO is the inherent propensity of the person in this position to embrace communication and negotiation abilities (Tagliavini et al., 2004; Chun and Mooney, 2009; Trigo et al., 2009; Waller et al., 2010).

The Controlling Activities of the CIO

Controlling activities tend to be practically-focused and are responsive to the organisational IT performance; allowing the CIO to gauge whether or not objectives are met. Hence, controlling activities relate to measuring performance with respect to expected standards, industry norms or organisational goals. The identified CIO position activities associated with controlling include:

- IT Performance: The undertaking of IT services performance is a reported activity of the CIO (Hunter, 2007). Other reported aspects of IT performance pertain to the overseeing of operational-level IT projects (Sojer et al., 2006; Currier, 2009)— where there is an expectation that performance measures will be in place.

- IT Maintenance: Part of the controlling activities undertaken by the CIO are noted as relating to having an understanding of IT corporate governance (Lane and Koronios, 2007)— arguably providing the formal structure in which IT operations and services are evaluated. Specific activities of the CIO noted under this focus-point are related to the firm’s capture of information and included the CIO maintaining security of data, as well as the integrity, confidentiality and quality of organisational information (Smaltz et al., 2006).

The CIO as an executive manager will engage in activities that by positional definition will be associated with each of these functional areas. Indeed, the position of CIO involves the undertaking of a set of diverse and multi-faceted tasks that are adaptable across all of these management functions. What is not clear from the literature is to what degree the reported activities typically make up the expected tasks of the CIO— tasks that are generally articulated in the recruitment process through job description documents.

Methodology

Research that uses content analysis as an investigative approach involves the development of well-defined grouping or classification categories before one attempts to segment and analyse the research data (Kellehear, 1993). These categories are normally grounded in the theoretical literature and provide the researcher with an unambiguous description of the important elements that are being studied. Content analysis can be applied to any form of data— examples of which include historical works, written text, images, television programs TV, websites and sounds. Kellehear (1993) suggests that content analysis can follow a series of practical steps so as to enhance the way that the research is undertaken, imparting elements of reproducibility and rigour into a study. The steps include:

- Selecting an appropriate sample to examine across a particular time frame.

- Deciding the context of the study with respect to sample size— whether it will be comprehensive and include all data, or exploratory for the purposes of refining categories by using a select sample.

- Scoring and/or counting observations as part of the systematic evaluation process

In this study, written text was the focus of analysis and was sourced from job descriptions that reflected the expected activities the contemporary CIO would encounter in the position. The recruitment of individuals to fill the CIO position will involve a job-design analysis reflecting organisational requirements noted in the recruitment process through job description documents. Indeed, the formal CIO job description can provide a reliable and appropriate source that records activities that would normally be expected to be undertaken as part of the position. The job description can be viewed as representing the organisational performance requirements of the CIO as well as reflecting the criteria for evaluating the CIO’s role— clearly a powerful information source that can allow the investigator insights into the CIO activity requirements. Furthermore, the study addresses Kellehear’s (1993) practical content analysis steps in the following way:

- Selecting an appropriate sample to examine across a particular time frame— The study used high profile job placement websites to source CIO job descriptions associated with Australian located firms. The sites searched included Seek.com (Australian based site only— US and UK available but not accessed), Mycareer.com.au (affiliated with the Melbourne Age newspaper) and CareerOne.com.au (affiliated with The Australian newspaper).

The search terms used to identify appropriate job descriptions were CIO and Chief Information Officer as well as other terms that have been noted as names that apply to the CIO position, including Director of IT and Vice President of IT (Broadbent and Kitzis, 2005; Banker et al., 2011). A check between each job description sourced from the career placement sites was undertaken to eliminate any duplicate job descriptions that had been advertised across multiple websites. Job descriptions that were specific for a noted operational area such as sales, operations, and so forth were not considered as top tier CIO positions and therefore, were not selected for the study.

- Deciding the context of the study with respect to sample size— The study has been deemed to be exploratory, allowing the categories of CIO activities identified form the literature to be further investigated. Hence, the number of job descriptions sampled was taken over a 5 month period (September 2010 to February 2011).

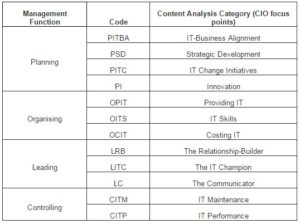

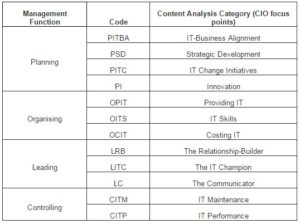

- Scoring and/or counting the observations as part of the systematic evaluation process— The analysis and evaluation of each job description used the identified CIO focus point categories that allowed keywords and themes associated with CIO activities to be allocated a specific job activity code. Table 3 identifies the codes used in the evaluation process and the type of job description activity they represent within the four management functions.

Table 3: CIO Focus Point Categories and Coding Used for Content Analysis

After each identified activity was assigned to a specific code, counting of each activity’s occurrence was undertaken. Counts allowed each CIO job activity to be rated for frequency, whilst the finding of any new activity allowed CIO focus point descriptions and categories to be expanded.

Results

The number of CIO-related vacancies in Australia that were advertised on the three job search websites over the 5 month period was 17. This small number of advertised positions might suggest that CIO recruitment by Australian organisations does not occur often. However, it can be assumed that being senior positions they would fall under the recruitment domain of professional employment services that would not use an online approach to recruit personnel, potentially adopting a more informal head-hunting channel to source the right person.

Content analysis of the job descriptions allowed 46 distinct activities to be identified and subsequently mapped to the areas of management planning, organizing, leading and controlling. In all, 156 activities were mentioned in the job descriptions and formed the basis of the study’s analysis (Table A1 in the appendix documents CIO activities). No single job description referred to all the CIO activities documented in the literature. Some job descriptions (J2. J3 & J8) did however, have a high number of references to the different CIO activities, whilst some descriptions (J5, J13 & J15) had a minimal number of references to CIO activity requirements. Several CIO job descriptions focused on specific activities that related to particular management areas— for example J5 only referred to providing and organizing activities. However, the majority of job descriptions were noted to have at least one activity that addressed each of the management areas— potentially reflecting CIO requirements that were general in nature.

Job Description Search Returns

Different search titles were used to identify advertised CIO position vacancies in accordance with naming conventions associated with the CIO position. Table 4 lists the different search titles that were used to identify the vacant CIO positions advertised in Australia.

Table 4: Search Returns for CIO Related Positions

Thirteen of the positions investigated in the study used either the Chief Information Officer or CIO as the descriptive job title for this position. Several job recruitment advertisements partitioned the role into a specific instructional department (Information Services) or highlighted a technological role associated with the position (Technology Officer). Only two Directors of IT positions were found using this particular search term— one position specific to a department (Infrastructure & Security). No job recruitment positions were located using the Vice President title, potentially reflecting that this title tends to be predominantly associated with North American firms.

Planning Activities of the CIO

Across the job descriptions analyzed, 12 distinct activities were assessed as having a planning focus (summarized in Table 5). The predominant activities noted as part of the CIO planning role were associated with the organisation’s strategic IT development. A CIO activity area not identified in the previous literature related to governance and policy (Code P) when it came to the introduction of IT within the organisation. Arguably, this fits under the strategic development focus, further reinforcing the nature of CIO planning activities required for delivering a strategically IT-focused solution to the firm.

Table 5: The CIO Activities Associated with Planning

Organising Activities of the CIO

Across the job descriptions analyzed, thirteen distinct activities were assessed to have an organizing focus (summarized in Table 6). The predominant tasks that were noted as part of the CIO’s organising activities involved the provision of IT— seemingly reflecting the organisation’s internal or external requirements. External requirements were associated with the notion that current day IT needs can be sourced from a third party provider, external to the organisation— the CIO having an important role in sourcing, evaluating, choosing and successfully managing this activity. Another aspect of the external environment is that a company might itself be a provider of IT services to other companies— having responsibilities for the provision of IT or services to these entities necessitates that the CIO manages the working-relationship with the firm’s client base. Hence, CIO organising activities embrace elements of managing IT provision and services that are internally relevant (having a focus on the organisation’s day to day requirements) and externally focused when engaging third-party IT providers or clients. Neither the internal nor the external focus of CIO activities were distinctively identified in the literature, thus providing an opportunity to further segment the Providing IT category (Code OPIT) to further segment this category into one that is either an internal or external company perspective. The organising activities of the CIO in the remaining two categories deal with IT costing and IT skills management. Costing activities that the CIO would be expected to undertake embrace elements of IT budgeting, sustainability and the economics of IT investments. IT skills provision has a focus on support through the development and management of cohesive teams.

Table 6: The CIO Activities Associated with Organizing

Leading Activities of the CIO

Across the job descriptions analyzed, 11 distinct activities were assessed as having a leadership focus (summarized in Table 7). A relatively high proportion of leading job-activities were noted to focus on the CIO as a relationship builder. CIO leadership generally involved engaging important people associated with the business, across different organisational levels, departments and also outside the firm. Hence, CIO leading activities were segmented into various sub-groupings based on the focus of the CIO activity— be it a general task that related to internal or external interaction with stakeholders or if the activity was aimed at the firm’s high-level senior executives.

The job-activities that were associated with the CIO being an IT champion predominately related to the technology section of the firm— the area that the CIO might directly oversee. These IT-champion activities involve the way that a CIO engages, motivates and directs staff/teams within the technology-focused sphere of the organisation. No explicit mention of the CIO directly championing the value of IT to other areas of the corporation is noted— arguably, this cross-organisational championing would be a tacit type of activity and not overtly documented in a job description. Notably, the CIO as a communicator was the activity least recorded across any of the management functions (Communication skills could possibly have been an assumed pre-requisite and not detailed in descriptions). Clearly, the CIO position has particular focus when it comes to relationship building (Code LRB)— an issue not previously documented in the literature. Hence, the study notes the distinctive groups of people that the CIO might engage with in relationship building activities. These are designated as either having a general internal-external focus or when the CIO needs to engage with senior executives.

Table 7: The CIO Activities Associated with the Leading Function of Management.

Controlling Activities of the CIO

Across the job descriptions analyzed, 9 distinct activities were assessed as having a controlling focus (summarized in Table 8). The controlling activities of the CIO have either a performance or maintenance focus. The greatest number of job-activities associated with controlling was in the IT performance category. The CIO activities related to IT performance involved measuring the value that IT delivers to the corporation through being able to manage the technology’s effectiveness, putting best practices in place, adhering to IT governance and introducing commercial standards. Enforcement and review of ICT are important activities that also fall under this category. The CIO IT maintenance activities included the highly critical area of business continuity planning and disaster recover.

Table 8: The CIO Activities Associated with the Controlling Function of Management

Content analysis of job descriptions has allowed the focus points of the CIO’s positional activities to be noted and documented from the four executive management areas— planning, organising, leading and controlling. Activities clearly had both internal and external-focused tasks across the areas associated with organising and leading. Within the organising function, the provision of IT can be viewed as a resource allocation activity that was directed toward either external entities (clients) or amongst firm-based departments (internal). Furthermore, CIO and organising and controlling activities have a focus on delivering short-term operational results, whilst those activities grouped to the planning function are intrinsically strategic and long-term with an emphasis on delivering results at some point in the future.

The activities attributable to the leadership domain are particularly distinctive with respect to relationship building issues— the CIO seemingly focusing on senior management in one aspect of the role, whilst counterbalancing relationship building activities with another distinct group of internal/external stakeholders.

Conclusion

This paper reports on research that documented CIO activities allowing the role to be documented and understood from what is commonly acknowledged as the four fundamentals areas of management. CIO job descriptions were used to identify the planning, organising, leading or controlling activities that are expected to be undertaken by this modern-day executive in his or her organisational role. An analysis of job descriptions allowed 46 distinct CIO activities to be identified which were almost equally noted across the four management areas, suggesting that the CIO skill requirements are not distinctive for one managerial function. Indeed, although the CIO role is usually touted as having a leadership role as one of the “C” suite of executives— the planning activities associated with new IT, innovation and business alignment appear to be also important requirements.

The study is exploratory in nature and only a relatively small number of job descriptions were analysed. Future research has two potential directions. The first is to expand the number of CIO job descriptions that can be analysed by sourcing a greater number not only from those in the public domain, but also from professional employment services. The second direction for future research is to use the existing areas identified under each of the four management function and undertake a survey amongst CIOs to capture their perceptions on how they value the activities they undertake from a management planning, organising, leading and controlling perspective.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

References

Banker, R. D., Pavlou, P. A. & Luftman, J. (2011). CIO Reporting Structure, Strategic Positioning, and Firm Performance. MIS Quarterly, 35 (2): pp/ 487-504.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Bartol, K., Tein, M., Mathews, G. & Sharma, B. (2008). ‘Management: A Pacific Rim Focus (5th ed),’ North Ryde,NSW: McGraw-Hill, Australia.

Google Scholar

Broadbent, M. & Kitzis, E. S. (2005). ‘The New CIO Leader: Setting the Agenda and Delivering Results,’ Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Campling, J., Poole, D., Wiesner, R. & Schermerhorn, J. R. (2008). ‘Management (3rd ed),’ Milton, Qld: Wiley, John Wiley & Son Australia, Ltd.

Chun, M. & Mooney, J. (2009). “CIO Roles and Responsiblities: Twenty-five Years of Evolution and Change,” Information and Management, 46 (5): pp. 323-334.

Publisher – Google Scholar

CISR-January (2009). ‘Research Briefing: The Future of the CIO,’ Mass: Center for Information Systems Research (CISR), Sloan Management School (MIT).

CISR-July (2005). ‘Research Briefing: What Makes an Effective CIO? The Perspective of Non-IT Executives,’ Mass: Center for Information Systems Research (CISR), Sloan Management School (MIT).

CISR-March (2008). ‘Research Briefing: How CIOs Allocate Their Time,’ Mass: Center for Information Systems Research (CISR), Sloan Management School (MIT).

Currier, G. (2009). ‘CIO Blowback (Research: CIO Role),’ CIOInsight, 2009 (5): pp. 24-32.

Grover, V., Jeong, S.- R., Kettinger, W. J . & Lee, C. C. (1993). “The Chief Information Officer: A Study of Managerial Roles,” Journal of Management Information Systems, 10 (2): pp. 107-130.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Head, B. (2008). ‘Profile-Marianne Broadbent: The Information Manger,’ The Melbourne Age: Next. 14 October 2008, p.8. Melbourne.

Hunter, G. M. (2007). Contemporary Chief Information Officers: Management Experiences, Hershey, PA: IGI Publishing.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Hunter, G. M. (2011). “The Duality of Information Technology Roles: A Case Study,” International Journal of Strategic Information Technology and Applications, 2 (1): pp. 37-47.

Publisher – Google Scholar

ICIS (2008). CIO Problems and Prospects (International Conference on Information Systems: Track 18)http://web.archive.org/web/20080115224447/http://www.icis2008.org/ [Accessed August 1, 2009].

Kellehear, A. (1993). The Unobtrusive Researcher: A Guide to Methods, St Leonards: Allen & Unwin.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Lane, M. S. & Koronios, A. (2007). “Critical Competencies Required for the Role of the Modern CIO,” Proceedings of the 18th Australasian Conference on Information Systems (ACIS). Research, Relevance and Rigour: Coming of Age (CD-ROM). 5-7 December 2007. Toowoomba, Queensland. pp. 1099-1109.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Li, Y., Tan, C.- H., Teo, H.- H. & Tan, B. C. Y. (2006). “Innovative Usage of Information Technology in Singapore Organizations: Do CIO Characteristics Make a Difference,” IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 53 (2): pp. 177-190.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Mukerji, D. (2000). ‘Managing Information: New Challenges & Perspectives,’ French Forest, NSW: Pearson Education.

Google Scholar

Parker, L. D. & Ritson, P. A. (2005). “Revisiting Fayol: Anticipating Contemporary Management,” British Journal of Management, 16 (2005): pp. 175-194.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Robbins, s., Bergman, R., Stagg, I. & Coulter, M. (2009). ‘Foundations of Management (3rd ed),’ French Forrest: Pearson Education Australia.

Schermerhorn, J. R. (2008). ‘Management (9th ed),’ Hokoben, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Sellitto, C. (2010). “The Planning, Organising, Leading and Controlling Activities of the Chief Information Officer (CIO) as Identified in the Contemporary Literature,” Global Business & Economics Anthology, 2 (2): pp. 166-173.

Publisher

Smaltz, D. H., Sambamurthy, V. & Agarwal, R. (2006). The Antecedents of CIO Role Effectiveness in Organizations: An Empirical Study in the Healthcare Sector,” IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 53 (2): pp. 207-222.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Sojer, M., Schläger, C. & Locher, C. (2006). “The CIO – Hype, Science and Reality,” Proceedings of the 14th European Conference on Information Systems (ECIS 2006). June 12 – 14, 2006. Göteborg, Sweeden. pp. 1-12.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Tagliavini, M., Moro, J., Ravarini, A. & Guimaraes, T. (2004). Important CIO Features for Successfully Managing IS Sub-functions Strategies for Managing IS/IT personnel, Hershey, PA: Idea Group Inc. pp. 64-90.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Trigo, A., Varajao, J., Oliveris, I. & Barroso, J. (2009). “Chief Information Officer’s Activities and Skills in Portuguese Large Companies,” Communications of the International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA), 10 (2009): pp. 64-71.

Publisher

Waller, G., Hallenbeck, G. & Rubenstruck, K. (2010). The CIO Edge: Seven Leadership Skills You Need to Drive Results, Boston: Harvard Business Review Press.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Weill, P. & Ross, J. W. (2004). IT Governance: How Top Performers Manage IT Decision Rights for Superior Results, Boston, MA: HBS Press.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Weill, P. & Ross, J. W. (2009). IT Savvy: What Top Executives Must Know to go From Pain to Gain, Boston, MA: HBS Press.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Williams, C. & McWilliams, A. (2010). ‘MGMT, 1st,’ South Melbourne: Cengage.

Wren, D. A. & Bedeian, A. G. (2009). ‘The Evolution of Mangement Thought (6th ed),’ Danvers, MA: John Wiley & Sons.

Table A1: CIO Job-Description Activities Noted for Executive Management Areas