Introduction

“The richness of all human groups lies in their communication” (Françoise Dolto: 1908-1988). Communication, to share your opinions and feelings with others, is a completely natural, spontaneous human act. The richness of this shared communication lies in the credence given to the person sending the message. The power of the communication grows with the possibility given to the receiver of passing on the message: this is word of mouth word of mouth (WOM). As it is a spontaneous, non-commercial form of communication (Lindgreen and Vanhamme, 2005), WOM guides people in their decision-making processes (Hawkins et al., 2004). The Internet has introduced a new form of WOM by making it possible for people who do not know each other to send and receive messages. With its much faster transmission speed than traditional WOM, and unlimited reach through space and time, eWOM influences consumers and their decision-making processes significantly (Cheung and Thadani, 2010; Kelley and Marx, 2011; Robinson et al., 2012; Charo et al., 2015). Consumer purchases are based on the information available on line (Lee et al., 2007). The opinions, experiences and feelings shared by others strongly influence purchase intentions (Pollach, 2008).

When it is negative, eWOM can have serious consequences for firms (Armelini and Vilanueva, 2011). One of the most direct consequences of negative WOM is the boycott, when consumers decide to stop purchasing the firm’s products. Whatever the reasons for the boycott, the starting point can be just a message shared on the Internet. This negative message is generally sent by a consumer who has had a negative experience with a product, brand or firm. The transmission speed of the message engenders in consumers a feeling of altruism and the desire to avoid the reoccurrence of the experience, leading them to pass it on to others. This snowballing effect can only affect the firm’s image (Reynolds, 2006) or even its future sales (Griffith, 2011; Charo et al., 2015). Only the way the negative message is perceived varies between consumers, depending on several factors. Two people may react very differently to the same message. Culture plays a significant role in interpersonal communication (Hall, 1976). It influences the adoption of WOM (Lam et al., 2009). Culture may affect perceptions of a message shared on the Internet and the effect of negative WOM on the intention to boycott the firm’s products. Many authors have studied eWOM and its repercussions for firms (Bickart and Schindler, 2001; Doh and Hwang, 2009; Huang et al., 2009; Park and Lee, 2009; Park and Kim, 2008; Sher and Lee, 2009; Xia and Bechwati 2008; Park et al., 2007; Lee and Lee, 2009; Kelley, 2011; Almana and Mirza, 2013; Charo et al., 2015 ), but, as far as we know, none of this research has examined how cultural variables can influence the decision to boycott products following negative eWOM. The aim of this research is to explore the role culture plays in the perceptions of negative message sent on the Internet, and its repercussions for boycott intentions.

Literature Review

Electronic word of mouth

Research on word of mouth (WOM) dates from the 1960s (Arndt 1967; Dichter 1966; Engel et al., 1969). WOM has been defined in several ways. Arndt (1967) gave one of the first definitions of WOM, considering it to be communication about products or firms between people that the firm has not hired. As the message is informal, people consider its source to be free from any commercial intention. The information shared does not stem from the firm, which differentiates WOM from viral marketing (Lindgreen and Vanhamme, 2005). Its spontaneity gives it influence over consumers. They give more credence to statements by other consumers than to those shared by the firm (Armelini and Vilanueva., 2011). WOM gives consumers the ability to share their opinions freely and guides them in their future decisions (Hawkins et al., 2004). Traditional communication theories propose that social communication comprises four main features: the sender of the message, the stimulus (the message), the receiver of the message, and the response (Hovland, 1948).

With the development of the Internet, the influence of consumers on each other via WOM increased enormously (Cheung and Thadani, 2010). Technology gave consumers’ words more power, and thus made WOM more persuasive (Litvin et al., 2008). The term eWOM refers to any comment, whether positive or negative, made by consumers about a product or a firm on the Internet (Hennig-Turau et al., 2004).

eWOM is transmitted much faster than traditional WOM. It can be sent in many different ways: forums and discussion groups, blogs, social networks, etc. (Goldsmith, 2006). Electronic communication is also more widely available, and for an indefinite period (Hennig-Thurau et. al., 2004; Sen, 2008; Park and Lee, 2009; Hung and Li; 2007; Lee et al., 2008). Unlike offline WOM, it is possible to measure the intensity of eWOM, since it is “observable”: the quantity of information shared on the Internet is accessible by all, the speed of transmission and the volume of comments shared is much greater than the opinions that people can obtain from people they know in non-electronic contexts (Chatterjee, 2001).

The most studied consumer responses to eWOM in the literature are purchase intentions (Bickart and Schindler, 2001; Doh and Hwang, 2009; Huang et al., 2009; Park and Lee, 2009; Park and Kim, 2008; Sher and Lee, 2009; Xia and Bechwati 2008; Park et al., 2007; Lee and Lee, 2009; Kelley, 2011; Charo et al., 2015), attitude towards products, brands and firms (Doh and Hwang, 2009; Lee et al., 2008; Lee and Youn, 2009), adoption and reuse of the information (Cheung et al., 2008; Cheung et al. 2009; Forman et al., 2008; Zhang and Watts, 2008; Lee and Youn, 2009), trust in the message (Awad and Ragowsky, 2008; Sen, 2008; Sen and Lerman, 2007) and intention to recommend the products of the firm involved in the eWOM (Kelley et Marx, 2011).

eWOM has broadened consumers’ reference groups and affects consumer behaviour in general (Sarma and Choudhury, 2015). Positive WOM increases purchasing likelihood, whilst negative WOM has the opposite effect (Gruen et al., 2005). eWOM also affects product assessment (Dellarocas, 2003; Bae and Lee, 2011), loyalty intentions (Litvin et al., 2008) and company image (Reynolds, 2006). According to Sundaram et al. (2008), in the context of eWOM, people could be motivated by (1) altruism, trying to help others avoid similar negative experiences; (2) their desire to reduce anxiety or anger by sharing their experience with others; (3) their desire for revenge and (4) their desire to find a solution to their problems.

Next, we will focus on one of the most direct consequences of negative WOM: boycotting.

Boycotting: Definition of the Concept and Motivations

Boycotting is understood as an act of resistance to consumption, as one type of consumer reaction to crises (Mitroff et al., 1996). A boycott signifies a breakdown in the relationship between the firm and the consumer, where trust between them has been damaged. The boycott has been defined as “an attempt by one or more parties to achieve certain objectives by urging individual consumers to refrain from making certain purchases in the marketplace” (Friedman, 1985, p. 97).

Muraro-Cochart (2003) observed that one potential reaction of consumers to a crisis suffered by the firm is a boycott or negative word of mouth. This negative word of mouth tends to affect the sales of a given product, visits to sales outlets, attempts by other consumers to change behaviour, etc.

The boycott is also an intriguing form of consumer behaviour that remains underexplored. This little-known concept involves deciding to abstain from purchasing or consuming as a result of considerations and motivations that are intrinsic or extrinsic to the consumer. Few authors have investigated these motivations, and the field remains exploratory, particularly in cases initially generated on line.

The boycott is understood from a social perspective, as expressing what the consumer should choose to do, and signifying a contrast between the individual’s desire to consume and the group’s desire to abstain from consuming (Sen et al., Morwitz, 2001).

Braunsberger and Buckler (2011) have identified three main reasons for a boycott: (1) instrumental reasons, the desire to influence the target to make clear changes; (2) non-instrumental motivations, otherwise known as expressive boycotting (Capelli et al., 2012) where consumers express their dissatisfaction with the firm. This type of boycott can be initiated individually as a protest, or by following the actions of others; (3) the consequences engendered by the boycott in the sense that the more alternative, good quality products there are, the lower the cost.

Capelli et al. (2012) note a fourth, moral reason. It is based on the individual’s desire to maintain his/her intrinsic values and his/her self-esteem (John and Klein, 2003). Consumers decide to boycott when they consider that the product contradicts their value system. Garrett (1987) identified six determinants for participation in a boycott: la consumer awareness, values of potential participants, consistency of the aims of the boycott with the attitudes of participants, cost of participation, social pressure and the credibility of the boycott’s leadership.

Few studies have focused on the motivations leading to consumer boycotts (Klein et al., 2004). Most research on boycotts has been descriptive and conceptual (Klein et al., 2004). Nonetheless, the literature does identify a number of cultural factors that influence consumer behaviour. The role of these cultural factors is related to the concept of the boycott as “occurring when a number of people abstain from buying a product, at the same time, in reaction to the same act or serious behaviour, but not necessarily for the same reasons” (John and Klein, 2003, p. 1198). These authors consider that the boycott or the intention to boycott arises following a serious action by the firm. This action may involve signals that are in opposition to the individual’s cultural background.

Each person has his/her own cultural background, and assesses stimuli by comparing the signals transmitted by the stimulus to his/her own standards. This assessment is based on assimilation, or Social Judgement Theory (Sherif and Hovland, 1961). When there is a gap between the signals broadcast by the firm and the individual’s cultural background, this can result in a feeling of discomfort appears that can generate a crisis between the two parties. Boycotts or boycotting intentions are initiated for cultural reasons. Jensen (2008) observed that for religious reasons, Muslims decided to boycott Danish products following the publication in a Danish newspaper of illustrations disrespectful to the prophet Mohammed.

Moreover, a boycott is not only a collective action. It shows above all a personal commitment and is an act of resistance against the firm (Cissé-Depardon and N’Goala, 2009). This act of resistance is a form of expression of the consumer’s values; their refusal to consume is in line with their value system. Despite the various studies of boycotts and their motivations, the links with eWOM and the consumer’s culture have not been so far investigated.

Methodology

The literature has analysed the role of culture in determining the frequency and intensity of traditional WOM (Money et al., 1998). For example, research has demonstrated that people in individualistic cultures are more independent and nonconformist than in other cultures (Albers-Miller et Gelb, 1996). Thus, they are less sensitive to WOM. However, collectivist societies are more consensual (Lin, 2001). The consumers’ culture may determine their understanding of WOM and their probable reaction. The link between cultural variables and eWOM has rarely been explored (Pentina et al., 2015), even less so with regard to boycotts as the consequence of negative WOM. Hence, we used qualitative methods. Our method comprised two stages: netnography and focus group meetings.

Netnography

Netnography is a qualitative research method that consists in analysing comments made by Internet users: messages posted in discussion forums, exchanges in chatrooms, email, etc. The aim is to understand a marketing problem by analysing communities to discover research avenues or understand a little-known phenomenon that users discuss on line (Kozinets et al., 2010).

The main purpose of our netnography was to list all messages initiating negative WOM on social networks and to note the different comments of those who replied. We respected the stages recommended by Kozinets (2010):

- Starting-point: we chose a Facebook group, “Les bons plans de Tunisie: officiel” (good ideas for Tunisia). Most members of the group are Tunisian Internet users looking for good deals. We chose this group mainly because its members change regularly, it is regularly updated, it sees heavy user traffic, and a wide variety of messages are posted creating negative WOM. Its aim is to share good deals, tips, ideas, promotions, and also to discuss “bad deals.”

- Data collection: the members shared several negative messages. We analysed the different comments posted by members to understand their reactions. The negative messages chosen concerned products, brands, television channels and staff members (generally sales assistants) who had provoked negative reactions by consumers.

- Data analysis and interpretation: we sorted the messages, identifying those that had generated negative WOM. We also analysed the comments by other consumers, sorting them into types of reaction and intentions.

- Validation by participants and ethics: we contacted the participants to discuss and confirm our main findings.

This stage provided us with a broad understanding of the determinants of boycott intentions following negative eWOM. We also identified a number of cultural variables. To analyse our finding in more depth, we recruited participants for a second qualitative research method: focus group meetings.

Focus Group Meetings

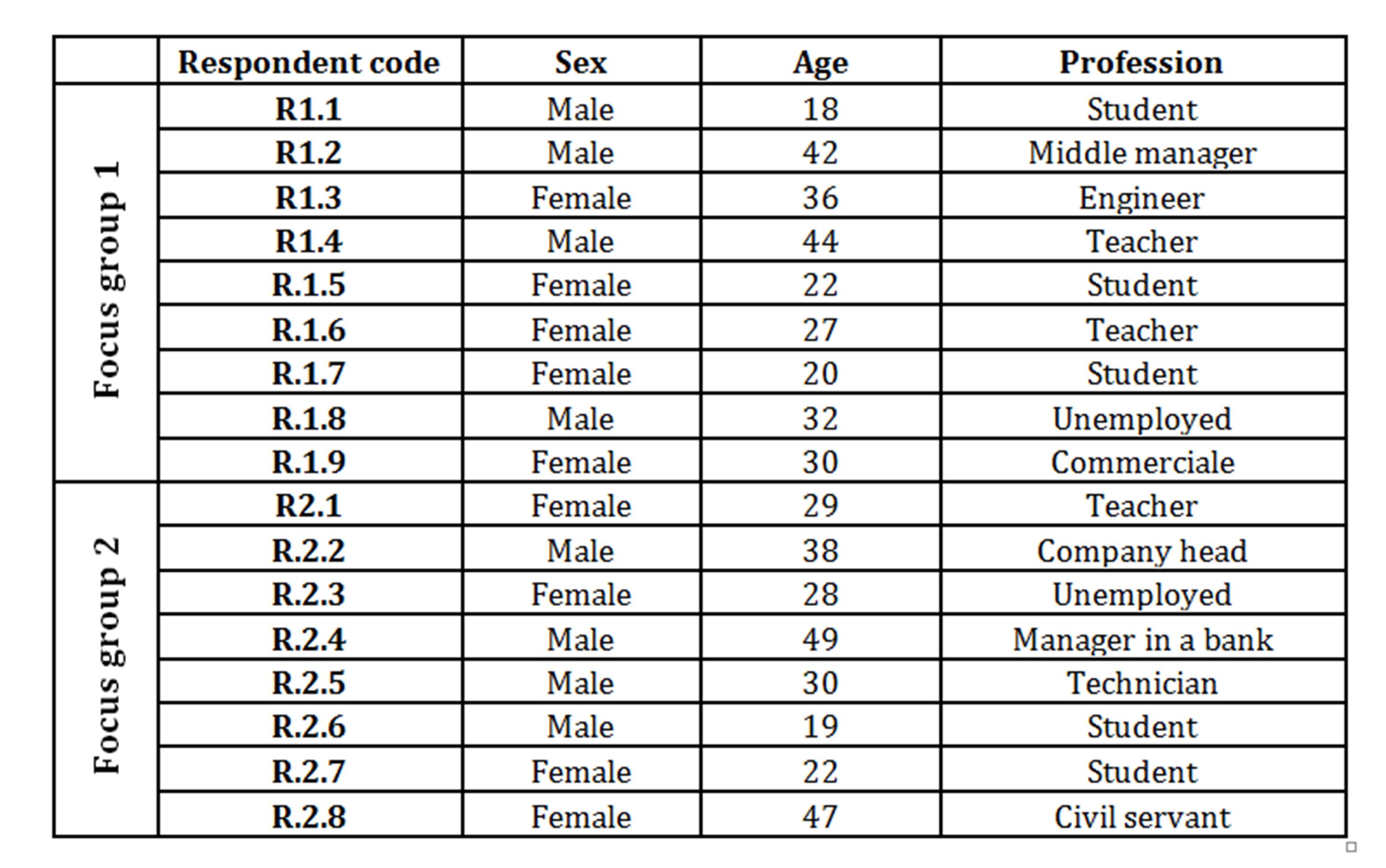

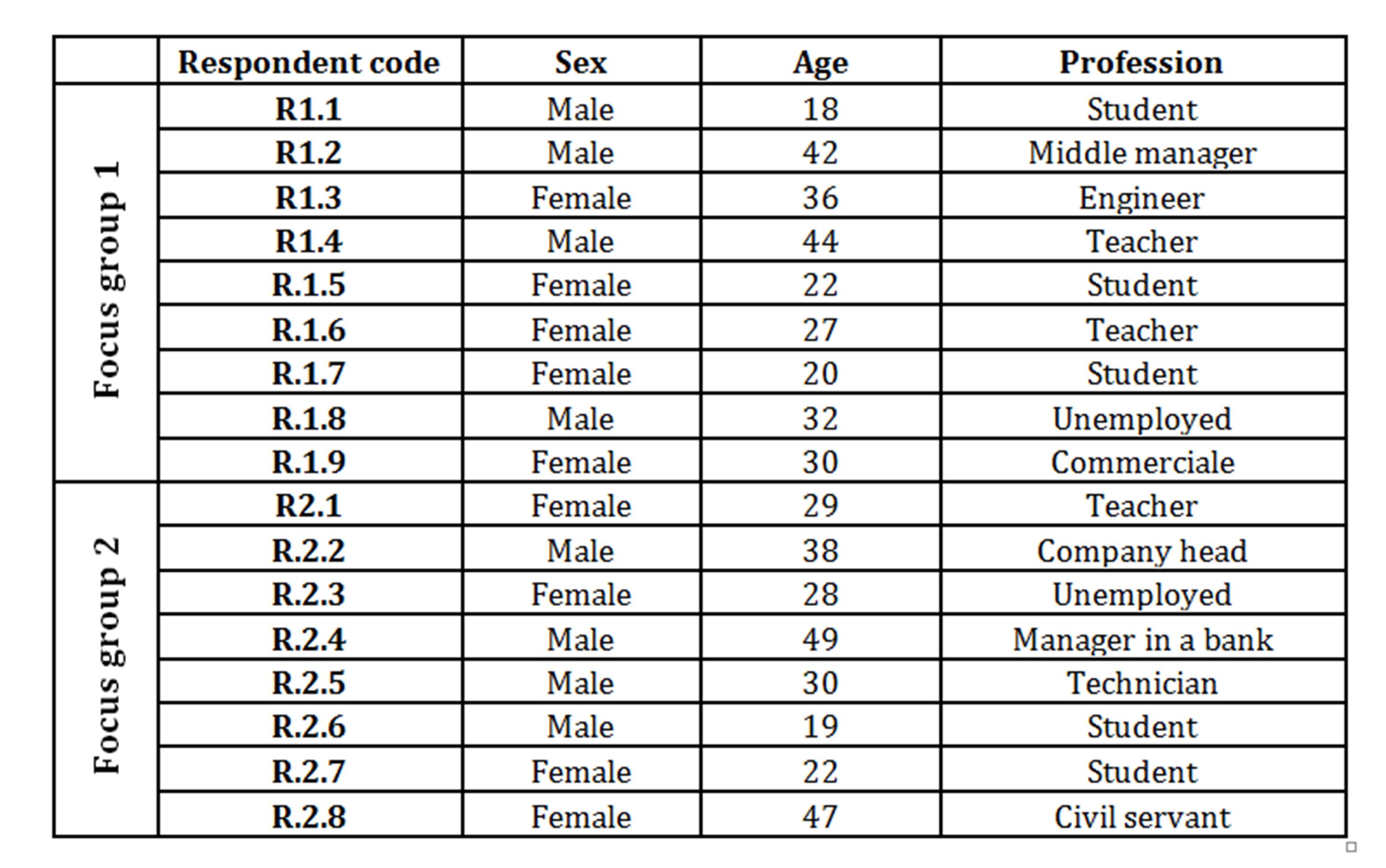

After listing all the negative comments made by Internet users, we contacted the members of the Facebook group to organise focus group meetings. We set up two groups of eight and nine members. The members of each group were of different sex, ages, professions and educational level (Table 1). The group meetings lasted on average between 60 and 75 minutes and discussed four topics:

- Messages that had recently generated negative eWOM;

- The reasons for these negative perceptions;

- The different consequences of these perceptions;

- Boycotting and its “cultural” motivations.

Table 1: Characteristics of The Qualitative Sample

The groups discussed the topics mentioned above. They identified several messages that had generated negative WOM, gave the reasons why they considered the messages as negative, gave examples of repercussions of this negative WOM on their behaviour, and finally spoke of the intention to boycott certain products and brands. Their cultural motivations emerged as they explained their different negative perceptions and the repercussions on their attitude towards certain brand. We recorded and transcribed the discussions.

We conducted a manual, thematic, analysis of the data collected through the netnography and the focus groups. Our coding process comprised three stages (Miles et Huberman, 2003) : (1) open in vivo coding to identify all the topics, without considering hierarchical relations between them faire; (2) axial coding, during which we went back and forth between the literature and the topics identified in our open coding, mainly to re-examine cultural variables in the literature and their relationship with negative WOM and boycott intentions; (3) selective coding to re-organise the themes logically and hierarchically.

Results

Figure 1 summarises the principal results of our thematic analysis. They highlight the role of negative eWOM in determining off-line consumer behaviour, and more precisely boycott intentions. They also emphasise how cultural variables significantly influence perceptions of messages that generate WOM on social networks, and intentions to boycott the brands, products, places or firms involved by this WOM.

Figure 1: e WOM and boycott intentions: role of cultural variables

Role of Ewom in Determining a Boycott

eWOM is the forerunner of the consumer’s decision to take part in a boycott. Most of our respondents agreed that the information shared on social networks influences their decision-making.

“As we’re on Facebook all the time, all the news and calls to boycott are easily and instantaneously shared among the members. When I read negative comments, I am more inclined to take part in a boycott” (R1.3, 36).

Some respondents mentioned the role of negative eWOM in the information processing and assimilation process. At the beginning of this process, comments and information are shared. The receiver of the message decodes the negative WOM and takes a decision that can take the form of an intention to boycott. Finally, as they are convinced that the decision is well-founded, they can call on others to take part in the boycott via the social networks, and so becomes an active intermediary.

“When I see comments and calls to boycott on Facebook, I sometimes take part in the action. I make my own analysis and take the decision to take part or not. If I am persuaded that the cause is right, I share the call to boycott” (R2.5, 30).

Some interviewees mentioned the fact that the credibility of the message sent and/or of the person who shares the message is extremely important in the decision of whether or not to boycott.

“Before taking action, I make sure that the all facts have been honestly reported. The source is important to my choice” (R1.4, 44).

“We all have a Facebook friend who is known for their conscientiousness and sense of analysis. When they share a call to boycott, I tend to click on the event shared and to take part, because I consider that the data shared is reliable and I trust their interpretation” (R2.7, 39).

For most of the participants in our qualitative survey, it is important to make sure that the message is really true, before committing to a decision. This finding is in line with Garrett (1987), who stressed that the credibility of the message favours participation in a boycott. To ensure this credibility, it is important for the person who shares the information to be “reliable” and for the photos shared to be genuine rather than borrowed from an online image bank. In some cases, some firms send misleading messages to tarnish their competitors’ reputation. Certains consommateurs peuvent s’en rendre compte:

“I’ve already seen comments that just look like something published by a competitor! For example, a lot of restaurants create false profiles and say anything to influence people. But consumers aren’t taken in; sometimes it’s obvious that it’s just a smear!” (R.1.4, 44).

Cultural Variables Perception of Ewom

Cultural variables determine to a great extent how consumers perceive and interpret messages published by others. Most of our informants are strongly influenced by values when they interpret messages that have generated WOM. For example, some members of the group we studied for the netnography are more affected by messages condemning an event that damages a common good, such as the destruction of a century-old tree, whilst this does not shock others, who are more concerned by problems that affect them directly, such as unemployment or social inequality. Thus, “collectivists” tend to express their disapproval of everything that affects the group they belong to, or society in general.

“We’ve fed up with seeing every day our beautiful century-old trees felled in their hundreds! A tree takes dozens of years, from generation to generation, to grow and develop, and to offer us all its advantages. It takes just a few minutes for the greed and barbarism of a merchant to sacrifice it to his commercial interests, and to deprive future generations of its benefits.” (https://www.facebook.com/groups/plantesdinterieuretjardinsTunisie/permalink/10153934586884291/)

Meanwhile, people with strong religious values are more sensitive to messages concerning religion, and are more likely to share them. The “acculturated” pay less attention to such messages.

“These TV channels that dare to broadcast series during the month of Ramadan where they talk freely of alcohol, of living together, and where the actresses are almost naked… It is quite normal for me to share my disapproval; others need to know about it, it’s unbelievable that people keep watching them” (R.2.8, 47).

“Cultural” Motivations for Boycott Intentions

Most of our respondents note that the most widespread type of boycott is expressive, in the sense that it enables them to express their disapproval or anger with a firm whose behaviour is “incompatible” with their cultural background.

“When I decided to stop going to a teashop and to boycott it, it was because I am opposed to this type of barbarous practice that consists in tearing up a two-century-old tree just so that the teashop can have an uninterrupted view” (R1.2, 42).

“There’s a petition to sign, we must boycott this space” (https://www.facebook.com/groups/lesplandeTunis/search/?query=mirador)

Several comments posted on the forum and some members of our focus groups state that individual values are the main reason for boycotting.

“If I agree to the idea of boycotting a product, it’s because somewhere there is something that goes against my personal values” (R1.9, 30).

Some respondents stress the existence of a discrepancy between their individual values and the signals sent out by the firm. This distortion tends to increase boycott intentions.

“When I see that there is a divergence between my personal values and the message transmitted, the degree of anger will be greater, since the firm or sales outlet has shown a lack of respect for me. They are attacking me personally. I will be more inclined to intend to boycott” (R.1.2, 42).

Some respondents state that nationalism can motivate boycott intentions, in that their national cultural identity prevails over the considerations of the target.

“I love my country, and I find that some brands or places reflect our national identity. When they are under attack, our belief in and love for our country is violated” (R.1.4, 44).

This phenomenon is illustrated by a mobile telephone operator, whose name “Tunisiana” referred to the target country. When the name was changed during a rebranding exercise, clients realised that the operator was no longer Tunisian but from the Middle East. Some disapproved of this rejection of the symbolic name of the firm, and called for a boycott. Here, nationalism appears as a fundamental cultural variable when deciding on a boycott after negative eWOM. People are generally affected by any message emphasising that a firm or brand does not respect their love for their country.

“Why change the name? It carried meaning that was used consciously to express national identity” (R.2.1, 29).

Other respondents mention another cultural antecedent to boycott intentions: personal or social good. They act in a committed, socially responsible way to conserve nature and citizens’ rights before acting as consumers.

“A tearoom, the Phalène, which has invaded the pavement by building a terrace illegally preventing pedestrians from passing, with the covert agreement of the authorities, goes against my values. A call to boycott has been launched, and I took part in a demonstration in front of the tearoom” (R.2.8, 47).

“That reminds me that recently another tearoom, the Mirador felled a two hundred year-old tree just to improve the view. What right do they have to chop down a 200 year-old tree? It’s a chainsaw massacre! After our efforts, the owner was sentenced to nine months in prison. You mustn’t keep quiet; you have to react through boycotts to make the authorities react and make those who dare to damage nature think again” (R.2.1, 29) (see appendix 1).

Some participants mention that sometimes they answer calls to boycott in a “follow-my-leader” attitude, because they beling to social groups and do not want to breach the established rules. According to Kelman (1961), following the leader is one of the “lightest” forms of conformism. It consists in acquiescing to collective action simply to avoid the inconvenience of rejection or repression.

“Sometimes I take part in a boycott because a group I belong to is doing it. So, to avoid encouraging suspicions or questions, I take part in the action” (R.1.1, 18).

In certain cases people answer a call to boycott simply to declare their membership of a group that denounces particular actions. For example, they may defend the rights of homosexuals, to declare their “open mindedness”, without this really being their opinion; they continue to follow some of their friends on social networks who like to be seen.

“I have friends who don’t believe in the cause of the boycott, but do it just to be considered, like their friends, recognised as animal rights or nature defenders, who don’t believe in the cause either, because they follow models considered to be cool” (R.1.5, 22).

Other antecedents were mentioned, linked to taboos or values such as modesty and respect for others.

“I remember that during the holy month of Ramadan, large audiences including families were watching TV, and one TV channel was broadcasting series that involved contents with sexual references. This is unacceptable and inconsistent with our Arabic-Muslim and Tunisian culture. It shocked us at home and we answered positively the call to boycott the TV channel involved” (R.2.4, 49).

Our analysis of comments participants in our qualitative survey reveals a final cultural variable that appears to significantly influence consumers’ intentions to boycott certain brands, products or firms: the avoidance of uncertainty. According to Hofstede (1991), uncertainty is “the extent to which people worry when faced with unknown or uncertain situations. These feelings are expressed in different ways, including stress and the need for foreseeability: the need for rules, whether written or not” (p. 149-150). Indeed, some people take part in boycotts because they need to plan ahead, to have clear rules and take clearly determined action, in order to minimise their degree of ignorance of certain situations.

“It’s reassuring to be able to see what others have experienced. Facebook helps me a lot in this way; it has already helped me reduce the risk of being cheated by restaurants for example. If the service was mediocre for others, it would be the same for me. I don’t want to have the same experience, and other people’s experience enlightens me and helps me make the right decisions in the future” (R.1.3, 36).

Conclusion

Every day, millions of messages are shared on the Internet. Some of these draw the attention of other users more than others. Generally, this depends on the degree of importance that people give to the message. Some messages eventually create WOM, either positive or negative. At this stage, cultural variables can affect the perception of the message, such as values, religion, collectivism and acculturation. People’s values can influence the way they perceive the message. For example, some are attached to values such as social wellbeing and pay more attention to messages about social problems (ecology, social equality, etc.), whilst others, with strong religious values, will be more affected by that which goes against religion (nudity, etc.). Once the message has been perceived positively or negatively, cultural variables also act to determine consumers’ reactions to positive or negative WOM. Some people are more “conformist” than others, and will tend to follow in a spirit of solidarity and act like the other members of their reference group. Hence, they are more sensitive to shared action such as boycotts. Some take part in a boycott to avoid risk linked to the consumption of the product that has generated negative WOM, to control the uncertainty. They see the boycott as a way to plan and control. They can also be motivated by nationalism, when a firm harms their country. Here the consumer takes part in a boycott to defend their nation and the good of the country.

Cultural variables play a dual role: the first concerns perceptions of eWOM and the second concerns the reaction to this WOM and boycott intentions. This research enhances understanding of the role of culture in deciding on a boycott following negative eWOM. As firms do not control eWOM, they have to understand how consumers perceive, interpret and respond to the different messages that generate WOM on the Internet. They can recruit staff to closely supervise consumer reactions on social networks and intervene before the messages have become too widespread. They can also limit the “follow-my-leader” attitude of consumers by being transparent, explaining or even apologising to prevent the negative message being shared and to prevent consumer actions such as boycotts gaining momentum. Reacting in good time is one of the best solutions for firms to adopt in response to negative messages posted by their clients. Moreover, when designing their marketing buzz campaigns, managers should analyse all events that have generated online WOM to choose the themes for their campaign.

Future research could monitor the evolution of online events from their appearance to their circulation, and to the organisation of joint action by consumers. The process studied in each event could give a clearer idea of how people perceive, interpret and analyse messages posted by others. A longitudinal study would also be interesting, interviewing consumers at different moments in their life and monitoring how their reactions to negative WOM evolve. An intercultural study could capture the role of cultural variables in deciding a boycott in different cultures, and could identify all the variables that can affect consumer reactions to negative eWOM.

References

- Albers-Miller, ND. et Gelb, BD. (1996). Business advertising appeals as a mirror of cultural dimensions: A study of eleven countries. Journal of Advertising, 25 (4), 57-70.

Google Scholar

- Almana, AM. et Mirza, AA. (2013). The Impact of Electronic Word of Mouth on Consumers’ Purchasing Decisions. International Journal of Computer Applications, 82 (9), 23-31.

Google Scholar

- Andrew, J. et Klein, JG. (2003). The Boycott Puzzle: Consumer Motivations for Purchase Sacrifice. Management Science, 49 (9), 1196—1209.

Google Scholar

- Armelini, G. et Vilanueva, J. (2011). Adding Social Media to the Marketing Mix. IESEinsight, (9), 29-36.

Google Scholar

- Arndt, J. (1967). Role of Product-Related Conversations in the Diffusion of a New Product. Journal of Marketing Research, 4, 291-295.

Google Scholar

- Awad, NF. et Ragowsky, A. (2008). Establishing Trust in Electronic Commerce Through Online Word of Mouth: An Examination Across Genders. Journal of Management Information Systems, 24(4), 101-121.

Google Scholar

- Bae, S. et Lee, T. (2011). Gender differences in consumers’ perception of online consumer reviews, Electronic Commerce Research, 11 (2), 201-214.

Google Scholar

- Bickart, B. et Schindler, R. (2001). Internet Forums as Influential Sources of Consumer Information. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 15, 31-40.

Google Scholar

- Brodin, O. (2000), Les communautés virtuelles: Un potentiel marketing encore peu exploré, Décisions Marketing, No. 21 (Septembre-Décembre 2000), 47-56.

Google Scholar

- Capelli, S., Legrand, P. et Sabadie, W. (2012). Se taire, nier ou s’excuser : comment répondre à un appel au boycott ? Décision Marketing, numéro spécial Résistance des consommateurs et pratiques des entreprises, 68, 71-82.

Google Scholar

- Chatterjee, P. (2001). Online Reviews: Do Consumers Use Them? Advances in Consumer Research, 28, 129-133.

Google Scholar

- Charo, N., Sharma, P., Shaikh, S, Haseeb, A, et Sufya, MZ. (2015). Determining the Impact of Ewom on Brand Image and Purchase Intention through Adoption of Online Opinions, International Journal of Humanities and Management Sciences, 3 (1), 41-46.

- Cheung, CMK., Lee, MKO. et Rabjohn, N. (2008). The impact of electronic word of- mouth. Internet Research, 18 (3), 229-247.

Google Scholar

- Cheung, M., Luo, C., Sia, C. et Chen, H. (2009). Credibility of Electronic Word-of- Mouth: Informational and Normative Determinants of On-line Consumer Recommendations. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 13 (4), 9-38.

Google Scholar

- Cheung, CMK. et Thadani, DR. (2010). The Effectiveness of Electronic Word-of-Mouth Communication: A Literature Analysis, 23rd Bled eConference Trust: Implications for the Individual, Enterprises and Society, June 20 – 23, 2010; Bled, Slovenia.

Google Scholar

- Cissé-Depardon, K. et N’Goala, G. (2009). Les effets de la satisfaction, de la confiance et de l’engagement vis-à -vis d’une marque sur la participation des consommateurs à un boycott. Recherche et Applications en Marketing, 24 (1), 43-67.

Google Scholar

- Dellarocas, C. (2003). The digitization of word of mouth: promise and challenges of online feedback mechanisms, Management Science, 49, 1407-1424.

Google Scholar

- Dichter, E. (1966). How Word of Mouth Advertising Works. Harvard Business Review, 44, 147-166.

- Doh, SJ. et Hwang, JS. (2009). How Consumers Evaluate eWOM (Electronic Word-of-Mouth) Messages. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 12 (2), 193-197.

Google Scholar

- Engel, JF., Kegerreis, RJ., et Blackwell, RD (1969). Word-of-Mouth Communication by the Innovator. Journal of Marketing, 33, 5-19.

Google Scholar

- Forman, C., Ghose, A. et Wiesenfeld, B. (2008). Examining the Relationship Between Reviews and Sales: The Role of Reviewer Identity Disclosure in Electronic Markets. Information Systems Research, 19 (3), 291-313.

Google Scholar

- Friedman, M. (1985). Consumer Boycotts in the United States, 1970-1980: Contemporary Events in Historical Perspective. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 19 (1), 96-117.

Google Scholar

- Garrett, DE. (1987). The Effectiveness of Marketing Policy Boycotts: Environmental Opposition to Marketing. Journal of Marketing, 51 (April), 46—57.

Google Scholar

- Goldsmith, RE. (Ed.) (2006). Encyclopedia of E-Commerce, E-Government and Mobile Commerce. Idea Group Publishing.

- Griffith, E. (2011). Can social shopping finally take off?’, disponible sur: http://www.adweek. com/news/advertising-branding/can-social-shopping-finally-take-136611.

- Gruen TW., Osmonbekov, T, et Czaplewski, AJ. (2005). eWOM: the impact of customer-to-customer online know-how exchange on customer value and loyalty, Journal of Business Research, 59 (4), 449-456.

- Hall, ET. (1976). Beyond Culture. Doubleday, New York, NY.

- Hawkins, DI., Best, R. et Coney, KA. (2004). Consumer Behavior: Building Marketing Strategy, 9th ed. Boston: McGraw Hill.

- Hennig-Thurau, T., Gwinner, KP., Walsh, G. et Gremler, DD. (2004). Electronic Word-of-Mouth Via Consumer-Opinion Platforms: What Motivates Consumers to Articulate Themselves on the Internet? Journal of Interactive Marketing, 18 (1), 38-52.

Google Scholar

- Hofstede, G. (1991). Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind. London, UK:

Google Scholar

- McGraw-Hill. Hovland, CI. (1948). Social Communication. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 92(5), 371-375.

- Huang, P., Lurie, N. et Mitra, S. (2009). Searching for Experience on the Web: An Empirical Examination of Consumer Behavior for Search and Experience Goods. Journal of Marketing, 73 (2), 55-69.

Google Scholar

- Hung, KH. et Li, SY. (2007). The Influence of eWOM on Virtual Consumer Communities: Social Capital, Consumer Learning, and Behavioral Outcomes. Journal of Advertising Research, 47 (4), 485-495.

Google Scholar

- Jensen, HR. (2008). The Mohammed cartoons controversy and the boycott of Danish products in the Middle East. European Business Review, 20 (3), 275-289.

Google Scholar

- John, A. et Klein, JG. (2003). The boycott puzzle: consumer motivations for purchase sacrifice, Management science, 49 (9), 1196-1209.

Google Scholar

- Kelley, OR., Marx, S., (2011). How young, technical consumers assess online WOM credibility. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 14 (4), 330-359

Google Scholar

- Kelman, HC. (1961). Processes of opinion change. Public Opinion Quarterly, 25, spring 1961, 57-78.

Google Scholar

- Klein, JG., Smith, NC. et John, A. (2004). Why We Boycott: Consumer Motivations for Boycott Participation. Journal of Marketing, 68 (July 2004), 92—109.

Google Scholar

- Kozinets, RV. (2010). Doing ethnographic research online. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Lam, D. Lee, A. et Mizerski, R. (2009). The effects of cultural values in word-of-mouth communication. Journal of International Marketing, 17 (3), 55-70.

Google Scholar

- Lee, J., Park, DH., et Han, I. (2007). The effect of on-line consumer reviews on consumer purchasing intention: The moderating role of involvement. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 11 (4), 125-148.

Google Scholar

- Lee, J., Park, DH. et Han, I. (2008). The effect of negative online consumer reviews on product attitude: An information processing view. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 7 (3), 341-352.

Google Scholar

- Lee, J. et Lee, JN. (2009). Understanding the product information inference process in electronic word-of-mouth: An objectivity-subjectivity dichotomy perspective. Information & Management, 46 (5), 302-311.

Google Scholar

- Lee, M. et Youn, S. (2009). Electronic word of mouth (eWOM): How eWOM platforms influence consumer product judgement. International Journal of Advertising, 28 (3), 473-499.

- Lin, CA. (2001). Cultural values reflected in Chinese and American television advertising. Journal of Advertising, 30 (4), 83-94.

- Lindgreen, A. et Vanhamme, J. (2005). Viral Marketing: The Use of Surprise. Advances in electronic marketing, ch7.

- Litvin, SW., Goldsmith, RE., et Pan, B. (2008). Electronic word-of-mouth in hospitality and tourism management, Tourism Management, 29 (3), 458-468.

- Miles, M. et Huberman, MA. (2003). Analyse des données qualitatives (2ème édition). Bruxelles, De Boeck Université.

- Mitroff, II., Pearson, CM. et Harrington, LK. (1996). The Essential Guide to Managing Corporate Crises: A Step-by-Step Handbook for Surviving Major Catastrophes. Oxford University Press.

- Money, RB., Gilly, MC. et Graham, JL. (1998). Explorations of national culture and wordof-mouth referral behavior in the purchase of industrial services in the United States and Japan. The Journal of Marketing, 62 (4), 76-87.

Google Scholar

- Muraro-Cochart, M. (2003). La perception du risque de santé alimentaire: approfondissement conceptuel et perspectives managériales, 3ème congrès sur les tendances du marketing en Europe, ESCP —EAP, Venise.

- Park, DH., Lee, J. et Han, I. (2007). The Effect of On-Line Consumer Reviews on Consumer Purchasing Intention: The Moderating Role of Involvement. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 11 (4), 125-148.

- Park, DH. et Kim, S. (2008). The effects of consumer knowledge on message processing of electronic word-of-mouth via online consumer reviews. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 7 (4), 399-410.

- Park, C. et Lee, T. (2009). Information direction, website reputation and eWOM effect: A moderating role of product type. Journal of Business Research, 62 (1), 61-67.

Google Scholar

- Pentina, I., Basmanova, O., Zhang, L. et Ukis, Y. (2015). Exploring the Role of Culture in eWOM Adoption. MIS Review, 20 (2), March (2015), 1-26.

- Pollach, I. (2008). Electronic word-of-mouth: A genre approach to consumer communities. International Journal of Web Based Communities, 4 (3), 284—301.

- Reynolds, G. (2006). An army of Davids: How markets and technology empower ordinary people to beat big media, big government, and other Goliaths. Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson.

- Robinson, R., Goh, TT., et Zhang, R. (2012). Textual factors in online product reviews: a foundation for a more influential approach to opinion mining. Electronic Commerce Research, 12 (3), 301-330.

- Sarma, AD. et Choudhury, BR. (2015). Analyzing electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) in social media for consumer insights — a multidisciplinary approach. International Journal of Science, Technology & Management, Volume No 04, Special Issue No. 01, March 2015.

- Sen, S. (2008). Determinants of Consumer Trust of Virtual Word-of-Mouth: An Observation Study from a Retail Website. Journal of American Academy of Business, Cambridge, 14 (1), 30-35.

- Sen, S., Gürhan-Canli, Z. et Morwitz, V. (2001). Withholding Consumption: A Social Dilema Perspective on Consumer Boycotts. Journal of Consumer Research, 28 (3), 399—417.

- Sen, S. et Lerman, D. (2007). Why are you telling me this? An examination into negative consumer reviews on the Web. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 21 (4), 76-94.

- Sher, P. et Lee, S. (2009). Consumer Skepticism and Online Reviews: An Elaboration Likelihood Model Perspective. Social Behavior and Personality, 37 (1), 137-144.

- Sherif, M. et Hovland, CI. (1961). Social judgment: assimilation and contrast effects in communication and attitude change. New Haven,Yale University Press.

- Sundaram, DS., Mitra, K., et Webster, C. (1998). Word”of”Mouth Communications: A Motivational Analysis. Advances in Consumer Research, 25, 527—531.

- Xia, L. et Bechwati, N. (2008). Word of Mouse: The Role of Cognitive Personalization in Online Consumer Reviews. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 9 (1), 103-117.

- Zhang, W. et Watts, SA. (2008). Capitalizing on Content: Information Adoption in Two Online communities. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 9 (2), 73-94.

Google Scholar

Appendix

Appendix 1: Examples of photos generating negative WOM on Tunisian social networks

Appendix 1.1 Photos of the call to boycott the tearoom and pastry shop “Mirador,” which had felled a tree

Photos: https://www.facebook.com/groups/lesplandeTunis/search/?query=mirador

Appendix 1.2 Photos taken near the baker’s and pastry maker’s shop “le gourmet” to denounce the fact that staff throw rubbish on the pavement

Photos: https://www.facebook.com/groups/1008279892518211/search/?query=gourmet

Appendix 1.3 Photos of mouldy cheese sold by two Tunisian dairy product brands

Photos: https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=750173171755299&set=pcb.10260214274