Introduction

Cross-border merger and acquisition (M&A) are important for organizational growth and development. According to Pricewaterhouse Coopers (2011), cross-border M&A is essential for the local organizations to expand their market internationally. Over 80% of the Asia-based senior executives expected cross-border M&A for their companies in the next 12 months with almost 49% also consider to involve in cross-border M&A deal in the next 2 years (PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2011).

Despite current national economic fluctuation, many large organizations in Malaysia are still adopting cross-border M&A to acquire more international consumers, expand market share and offer better value to customers across borders. Cross-border M&A has been recognized as one of the tools for international expansion and diversification among local and government-linked companies (Barrock, 2006). For instance, Telekom Malaysia Berhad (TM) and Maxis communication Berhad, two local telecommunication companies, had ventured abroad by using cross-border M&A to acquire firms in India and Indonesia (Jayaseelan, 2006).

A half or more of cross-border M&A in Malaysia had resulted in a failure and did not achieve a good performance (Jansen, 2002). Socio-cultural change is one of the crucial factors of cross-border M&A failure, which is apparently difficult to control and manage by local organizations when M&A takes place across borders and language barriers (PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2011). Thomas and Kummer (2006) indicated that the socio-cultural factor may hinder cross-border knowledge transfer in M&A and impede local company from enjoying more benefits from cross-border M&A. However, at present, there is still a lack of research to investigate key socio-cultural factors affecting knowledge transfer in cross-border M&A. Among the very few previous literature that examine cultural impact on cross-border M&A performance, some previous studies revealed a negative impact of cultural factor on the performance of international M&A (Datta & Puia, 1995; Olie, 1994; Geschwind, Melin & Wedlin, 2016), while some studies identified a positive relationship (Sousa & Bradley, 2015). Other studies indicated either no direct cultural impact on international M&A performance (Efthyvoulou, Bamiatzi, & Jabbour, 2016) or the least significant impact on M&A performance (Kanter and Corn, 1994).

Many of the previous cross-border M&A studies were either fragmented (Larsson & Finkelstein, 1999; Deng, 2010) or scattered (Kish & Vasconcellos, 1993). None of the previous studies has focused on examining knowledge transfer in cross-border M&A. Therefore, this study is timely and relevant to help improve Malaysian companies’ knowledge transfer strategy in cross-border M&A.

This research is therefore conducted to provide a holistic research framework that incorporates key socio-cultural factors affecting knowledge transfer in cross-border M&A. This research will provide empirical suggestion to domestic companies to improve the current management of cultural differences that may be the main reason for the high failure rates of knowledge transfer in international M&A.

Literature Review

Knowledge Transfer in Cross-Border M&A

Knowledge transfer is the movement of knowledge among different departments, units, or organizations rather than individuals (Ko, Kirsh & King, 2005; Zhou, Fey, & Yildiz, 2015). Knowledge transfer included transfer of tangible information and intellectual property, expertise, experience, learning and skills (Kalar & Antoncic, 2015). Knowledge transfer across borders in international M&A includes the movement of tacit knowledge, which resides in the individual head, and explicit knowledge, which is clearly recorded in reports, documents, articulated and captured among employees in headquarter and international subsidiaries (Veiru & Rivard, 2015).

The following factor may have significant effect on the success of knowledge transfer in cross-border M&A:

Organizational Cultural Differences

The first factor that influences the knowledge transfer in cross-border M&A is organizational cultural differences. Organizational culture is a system and common belief, shared assumptions, values shaped by organizational members (Bauer, Matzler, & Wolf, 2016). According to Kruger and Johnson (2011), organizational cultural is able to support knowledge transfer and facilitate learning among employees in headquarter and international subsidiaries.

Organizational cultural differences may reflect differences in the ability to identify, transfer and implement potentially useful knowledge among employees in headquarter and international subsidiaries (Sirmon & Lane, 2004). Organizational cultural differences increase social conflict and have negative impact on knowledge transfer. Organizational cultural differences can also be a source of capability development and value creation on knowledge (Morosini, 1998; Lee, Kim & Park, 2015). Therefore the following hypothesis is tested in this study:

H1: There is a negative significant relationship between organizational cultural differences and knowledge transfer in cross-border M&A.

Relationship and Trust

The next factor, relationship and trust, is also important for knowledge transfer in cross-border M&A. The interaction and knowledge transfer between employees from headquarter and international subsidiaries determine whether both parties can obtain the greatest benefits during the interaction and collaborative alliances (Appelbaum, Roberts, & Shapiro, 2013). International counterpart which is lack of complementary knowledge may cause conflict and instability in alliances, which will eventually affect the efficiency and effectiveness of knowledge transfer process (Lander & Kooning, 2013; Van Gorp & Honnefelder, 2015). Similarly, lack of mutual trust among international affiliates may result in knowledge silos due to the lack of credibility and trustworthiness in the working relationship across borders (Shah, & Coyne, 2012). Therefore the following hypothesis is tested in this study:

H2: There is a positive significant relationship between relationship and trust and knowledge transfer in cross-border M&A.

Knowledge leadership

The next factor, knowledge leadership, supporting organizational climate for learning, may also affect knowledge transfer in cross-border M&A (Puusa, & Kekäle, 2013; Zhang, 2014). It is important for company leaders to learn from both past and current decision to ensure organizational effectiveness. A transformative leader can exploit their knowledge in forming international working communities and cross-functional teams after cross-border M&A to enhance employee’s commitment and reduce ambiguity in the cross-border collaboration among employees from different countries (Piper & Schneider, 2015). Therefore the following hypothesis is tested in this study:

H3: There is a positive significant relationship between knowledge leadership and knowledge transfer in cross-border M&A.

Employee Job Satisfaction

Cross-border M&A is more likely to be accompanied with job dissatisfaction, which will lead to unwillingness to participate in knowledge transfer, increased turnover and absenteeism. Employees become the key point of the merger failures. Failure to communicate leaves employees to feel uncertain about their future that will cause more anxiety and significantly increase the level of employee anxiety, tension and stress (Giessner, Dawson, & West, 2013; Kyei-Poku, & Miller, 2013).

However, if the organization is able to understand its employees’ needs and adopt measures to improve their job satisfaction after the cross-border, it will tremendously improve the participation in cross-border knowledge transfer and the success rate of international M&A (Thompson & Phua, 2012; Vetter, 2014). Therefore the following hypothesis is tested in this study:

H4: There is a positive significant relationship between employee job satisfaction and knowledge transfer in cross-border M&A.

Research Methodology

A total of 10 domestic companies in Malaysia which had involved in cross-border M&A in the past 5 years participated in this study. The M&A cases were collected from the Thomson One Banker database. At the same time, this research has also cross-verified the selected cases with the Securities Commission and Bursa Malaysia. During company visits, questionnaires were distributed to managers who had been identified through a purposive sampling method based on a list provided by the participating organizations. A total of 200 managers were selected to participate in the survey.

The questionnaire is divided into two parts. The first part asks respondents to indicate their agreement or disagreement on 30 items measuring organizational cultural differences, relationship and trust, knowledge leadership and employee job satisfaction using a five-point scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The second part requested information on employees’ demographic data, such as age and gender.

Results

Demographics Profile

Most of the respondents belong to the age group 20 -25 years old (66.0 %). The second highest percentage is from the age group 26-30 years old (22.5 %). Meanwhile, the lowest percentage of respondents is from the group between 31-35 years old at the percentage of 11.5 %. There are 94 (47.0 %) Males and 106 (53.0 %) Female respondents. The two genders of the sample respondents are nearly fairly distributed.

Reliability Test

Reliability test is used to check the consistency of items in the questionnaire. Cronbach’s alpha was reliability coefficient, allowed to see how close the items related to each other. Table 2 presented the result of reliability test on four independent variables and one dependent variable. The total five variables are reliable to be used in this research. The alpha values ranging from 0.70 to 0.90 are considered acceptable or better for a research, indicating that items measuring each variable are reliable.

Multiple Linear Regression

Multiple linear regression is used to test the independent and dependent variable. It is used to measure the degree of corresponding of independent variables (organizational cultural difference, relationship and trust, knowledge leadership, employee job satisfaction) towards the dependent variable (knowledge transfer in cross-border merger and acquisition)

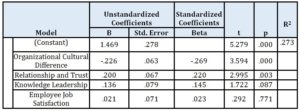

According to Table 1, organizational cultural difference (p = 0.000) and relationship and trust (p = 0.003) have significant influence towards knowledge transfer in cross-border M&A. Thus, H1 and H2 are supported. Organizational cultural difference has a significant negative influence on knowledge transfer in cross-border M&A (standardized beta coefficient =-.269) while relationship and trust has a significant positive influence on knowledge transfer in cross-border M&A (standardized beta coefficient = .220). Both factors explain 27.3% of the variance in knowledge transfer in cross-border M&A. However, knowledge leadership and employee job satisfaction are not statistically significant with knowledge transfer in cross-border M&A (p>0.05). Therefore, H3 and H4 are not supported.

Table 1: Multiple Linear Regressions

Discussion

The research aims to study the sociocultural factors that affect Knowledge Transfer in cross-border M&A in Malaysia. Organizational cultural difference and the relationship and trust were discovered to be the most influential factors in explaining the knowledge transfer in cross-border M&A.

Organizational cultural difference has significant negative impact on knowledge transfer in cross-border M&A. This result is in line with Bauer, Matzler and Wolf (2016), who discovered that organizational cultural difference has a negative influence on the knowledge transfer where different organizational practices among headquarter and international subsidiaries discourage cross-border knowledge transfer and delay organizational decision making. Efthyvoulou, Bamiatzi and Jabbour (2016) also stated that organizational cultural difference is important in ensuring the success of knowledge transfer. Enormous organizational cultural difference leads to organizational performance failure after cross-border M&A. According to Kalar and Antoncic, (2015), if the organizational cultural difference is ignored in cross-border knowledge transfer, it might contribute to poor M&A performance.

Therefore, in order to enhance participation in knowledge transfer after cross-border knowledge transfer, organizations should ensure a better understanding of the organizational structure, governance mechanism and business practices immediately after the M&A.

Relationship and trust is another factor, which positively influences knowledge transfer in cross-border M&A. Successful knowledge transfer in M&A required employees in both headquarter and international subsidiaries to build basic trust immediately after cross-border M&A and then enhance trust and relationship between employees across-border gradually. Strong trust and relationship are particularly important in the two-way interactions of both sender and receiver to transfer complex explicit knowledge or tacit knowledge.

Therefore, in order to enhance knowledge transfer in cross-border M&A, members in both headquarter and international subsidiaries should be encouraged to form an online community of practice so that they can share their solution to common organizational problems, learn from each other and understand the needs and requirements of each other.

The knowledge leadership is found not significantly important towards the success of knowledge transfer in cross-border M&A. Although Politis (2001) stated that good knowledge leadership is important in M&A to cultivate trust, discover and disseminate knowledge, this study discovered that knowledge leadership is not perceived as an important factor in guiding and motivating employees to effectively transfer knowledge after cross-border M&A. This is probably because most knowledge leaders in the organizations do not use their communication channels optimally and do not focus enough on efficient communication with the employees before and after cross-border M&A. Since communication is essential during major organizational change such as M&A, it is important for knowledge leaders to provide crucial real-time information to employees.

In order for organizations to enhance knowledge transfer across borders, communication from the top to the bottom should be implemented and correct data are essential to be communicated throughout all levels in the organization after M&A in order to ensure that employees know what will happen next. Clear communication from knowledge leader is essential during M&A process as it will effectively reduce the feeling of uncertainty and motivate the employee to be more engaged in cross-border knowledge transfer.

Theoretical Implication

The theoretical framework of this research provides a better perspective on key socio-cultural factors that influence knowledge transfer in cross-border M&A and it contributes to the literature of knowledge transfer in cross-border M&A, which is apparently under-researched.

The findings of this paper raise several interesting issues for future research. Key findings such as knowledge leadership and job satisfaction are not important in influencing knowledge transfer in cross-border M&A, suggest that at least in Malaysian acquisitions, there is the potential for improvements in the organizational leadership and operating performance so that employees will feel more happy and committed working in a big domestic with a lot of international business associates and cross-border M&A activities.

Managerial Implication

The main finding of this study is that organizational difference is crucial in determining the success of knowledge transfer in cross-border M&A. Hence, organizational practitioners should be cautioned of the dynamic nature of knowledge and the complexity to manage organizational difference in sharing and transferring knowledge. Better preparation and understanding of the requirements of the knowledge transfer process is essential before and after M&A. More employees should be involved from the very beginning of the planning of the knowledge transfer process in order to minimize the possible hardships and arising issues that the employees and company may need to undergo after cross-border M&A.

Another implication for practitioners is to emphasise more on motivation and communication of employees after M&A as motivation and communication serve as a virtue base for mutual understanding and trust. Employees will be more willing to share and transfer knowledge across borders if they are treated equally by the leaders and if there is strong relationship and trust among each other.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

References

Appelbaum, S. H., Roberts, J. and Shapiro, B.T. (2013). ‘Cultural strategies in M&As: Investigating ten case studies,’ Journal of Executive Education, 8(1), 3.

Barrock, J. (2006). ‘Forging partnerships: Petronas marks maiden foray into China,’ Bizweek, the Star, 4.

Bauer, F., Matzler, K. and Wolf, S. (2016). ‘M&A and innovation: The role of integration and cultural differences—A central European targets perspective,’ International Business Review, 25(1), 76-86.

Datta, D.K. and Puia, G. (1995). ‘Cross-border acquisitions: An examination of the influence of relatedness and cultural fit on shareholder value creation in US acquiring firms,’ MIR: Management International Review, 1(12), 337-359.

Deng, P. (2010). ‘Absorptive capacity and a failed cross-border M&A,’ Management Research Review, 33(7), 673-682.

Efthyvoulou, G., Bamiatzi, V. and Jabbour, L. (2016). ‘Foreign vs Domestic Acquisitions on Financial Risk Reduction,’ The Sheffield Economic Research Paper Series (SERPS), 2016003.

Geschwind, L., Melin, G. and Wedlin, L. (2016). ‘Mergers as Opportunities for Branding: The Making of the Linnaeus University,’ In Mergers in Higher Education (Vol. 2016, No. 1, pp. 129-143). Springer International Publishing.

Giessner, S. R., Dawson, J. and West, M. (2013). ‘Job satisfaction and supportive leadership during organizational merger,’ In Academy of Management Proceedings (Vol. 2013, No. 1, pp. 11590). Academy of Management.

Jayaseelan, R., Mitra, T. and Li, X. (2006). ‘Estimating the worst-case energy consumption of embedded software,’ In Real-Time and Embedded Technology and Applications Symposium, 2006. Proceedings of the 12th IEEE (pp. 81-90). IEEE.

Kalar, B., & Antoncic, B. (2015). ‘The entrepreneurial university, academic activities and technology and knowledge transfer in four European countries.’ Technovation, 36(1), 1-11.

Kish, R.J. and Vasconcellos, G.M. (1993). ‘An empirical analysis of factors affecting cross-border acquisitions: US-Japan,’ MIR: Management International Review, 1(1), 227-245.

Ko, D.G., Kirsch, L.J. and King, W.R. (2005). ‘Antecedents of knowledge transfer from consultants to clients in enterprise system implementations,’ MIS quarterly, 29(1), 59-85.

Kruger, C.J. and Johnson, R.D. (2011). ‘Is there a correlation between knowledge management maturity and organizational performance?’ Vine, 41(3), 265-295.

Kyei-Poku, I.A. and Miller, D. (2013). ‘Impact of employee merger satisfaction on organizational commitment and turnover intentions: a study of a Canadian Financial Institution,’ International Journal of Management, 30(4), 205.

Lander, M.W. and Kooning, L. (2013). Boarding the aircraft: Trust development amongst negotiators of a complex merger. Journal of Management Studies, 50(1), 1-30.

Larsson, R. and Finkelstein, S. (1999). ‘Integrating strategic, organizational, and human resource perspectives on mergers and acquisitions: A case survey of synergy realization,’ Organization science, 10(1), 1-26.

Lee, S. J., Kim, J. and Park, B.I. (2015). ‘Culture clashes in cross-border mergers and acquisitions: A case study of Sweden’s Volvo and South Korea’s Samsung,’ International Business Review, 24(4), 580-593.

Morosini, P., Shane, S. and Singh, H. (1998). ‘National cultural distance and cross-border acquisition performance,’ Journal of international business studies, 137-158.

Olie, R. (1994). ‘Shades of culture and institutions-in international mergers,’ Organization Studies, 15(3), 381-405.

Piper, L.R. and Schneider, M. (2015). ‘Nurse Executive Leadership during Organizational Mergers,’ Journal of Nursing Administration, 45(12), 592-594.

(2011). “Intersections Fourth-quarter 2011 Transportation and Logistics Industry Mergers Acquisitions and Analysis” [Online], [Retrieved February 2, 2016], http://www.pwc.com/us/industrialproducts.