Introduction

In response to global and domestic competition, Cooke (1994) pointed out more than twenty years ago that (here: American) companies try to improve their business performance through a more effective use of their available work forces with the implementation of employee participation programmes. For this reason, it is a popular practice among shareholders and investors to appropriately involve executive employees in target corporate success (Poenicke and Buenning 2014). These days, there is, in the private equity context, hardly any transaction without the participation of the management in a purchased target company (Hohaus and Inhester, 2003). Furthermore, family-equity investments, i.e. the participation of family offices in successful companies, also regularly use such instruments (Schulte, 2016).

The reasons for the implementation of management participation programmes in typical Leveraged-Buy-Out Transactions are diverse, but boil down to a sustained increase in corporate value. The managers participate in the chances and risks of the current business activities as an incentive for better work performance. For these reasons, managers often get the chance to purchase shares of amounts equal to one or two gross annual salaries.

The legal form of the management participation or co-investment programmes can be very diverse, e.g. stock options, preferred shares, rights embodied in a participation certificate, indirect participations etc.

Such (indirect) participation in the target companies needs to be efficiently designed for both parties. For this reason, in medium-sized or large buy outs, the management participation would typically be bundled into a separate investment vehicle (see Section 3). By way of an equity contribution to the investment vehicle, the managers receive shares in the investment vehicle, representing an indirect participation in the target company. The investment through a vehicle also facilitates the administration, when many managers from several countries are to participate in the target company. In this article, such programmes will be reviewed with regard to their prominent position in practice (Thiele, 2017).

In the context of the purchase of the participation in an investment vehicle, all parties enter into a co-investor and shareholders’ agreement with respect to their holding of shares in the target company. In such agreements, the terms and conditions are codified, especially with respect to exit clauses, leaver schemes, drag-along-right, tag-along-right, anti-dilution-protection, and other aspects like admission of further co-investors.

The terms and conditions of these agreements especially are regularly scrutinized by the tax authorities. Most frequently, the central question in this context is whether a co-investment/equity participation of a manager in the target company (directly or indirectly) represents an additional source of income apart from the person’s employment relationship in the target organization. And, in case of an exit, whether the capital gains out of the disposal of the shares held by managers in an investment vehicle represent capital income at the level of the manager. In some cases, the tax authorities consider capital gains to be wages because of a close connection between employment in the target and capital investment. The huge tax impacts of these re-qualifications of capital gain in work income will be shown in Section 4.

Review of Scientific Journals, Views of Fiscal Authorities, and Federal Fiscal Court Decisions

Within the usual tax audits done by the fiscal authorities, management participation programmes have been focused on for many years (Poenicke and Buenning, 2014). In management participation programmes, the main tussle between the fiscal authorities and the managers results in a fiscal treatment of these programmes and the revenues earned from them (e.g. profit distributions, capital gains).

It is necessary for all parties to differentiate between the employment contract of the manager and the special right resulting in the capital participation of the managers (indirectly) in the target company, where they also happen to be employed. Such an agreement is generally accepted by the German Federal Fiscal Court as a separate privity of contract, which is independent of the employment contract (BFH, 2005; BFH, 2006; BFH, 2008; BFH, 2009; BFH, 2014; BFH, 2016a, BFH, 2016b). For this reason, the capital contribution needs to be concluded in an independent agreement next to the employment contract (BFH, 2016b).

Questions and uncertainties arise in cases where the employment contract and capital participation are closely connected. That might be in cases where the benefits of profiting from a separate capital contribution are induced by the employment relationship as a kind of remuneration for work (BFH, 2009). It is a kind of sweet equity contribution, which means a manager receives capital contribution in the target company freely or at a cheap rate, overlapping the special right, resulting in a capital participation through the employment contract (von Braunschweig, 1998; Hohaus and Inhester, 2003; Poenicke and Buenning, 2014). So, such an agreement would totally qualify as wage, which would include (i) the non-cash benefit arising from the reduced or free purchase price of capital contribution, (ii) revenues from this participation, and (iii) the capital gain at the time of disposal of the participation represents wage according to German Income Tax Act (ITA 2009). In contrast, no action under the German tax law would be evoked, if the target company or the investor would grant a loan to the managers in order to enable them to finance the capital participation in the target (BFH, 2010). In this case, it would be necessary to determine the loan conditions in accordance with the arm’s length principle (Hohaus and Inhester, 2003).

Another big issue in the management participation programmes, which has been challenged for many years in the tax audits, is the leaver scheme in the co-investment programmes. In practice, the management participation programmes differentiate between managers who leave the company as “Good-Leavers”, “Bad-Leavers” and, where appropriate, as “Bad-Bad-Leavers”. As a general rule (Koch-Schulte, 2015), the leaver-types can be characterized as follows: (i) a Good-Leaver is manager who is unable to work anymore or dies or the employment contract is terminated by the target company, (ii) a Bad-Leaver is a manager who terminated the programme or the employment contract, or becomes insolvent, and (iii) a Bad-Bad-Leaver is a manager who breaches the manager’s duty and/or is dismissed for that (an important) reason.

With regard to such leaver schemes, the tax authorities argue in favour of an overlapping of the employment contract and the separate capital participation through the management participation programmes (Koch-Schulte 2015, FG Cologne 2015). This is based on a very special decision of the fiscal court in which a bad-leaver arrangement in a co-investment programme led to an overlapping of the parallel contracts of employment and capital participation (BFH 2013). Basically, other underlying aspects of these decisions must be taken into account. However, the tax authorities have come to consider this decision to be universally valid. This leads, in practice, to the conclusion that the tax authorities assumed an overlapping of the employment and the capital investment solely based on a bad-leaver scheme in a management participation programme (Roedding, 2017).

In this context, another senate of the German Federal Fiscal Court has contradicted the authorities’ interpretation by a decision published in 2017 (BFH, 2016b). According to the Federal Fiscal Court, there is, on the one hand, no overlapping of the employment contract in cases where the management participation programme is solely offered to a closed group of employees. On the other hand, leaver schemes, as described at the level of the management participation programme, are a consequence of these programmes, independent of the employment contract (BFH, 2010; BFH, 2016b).

Consequently, a leaver scheme on its own is not harmful from the tax point of view. The management programme must be considered with an overall view, if there is a close connection between the employment contract and the capital investment of a manager. Moreover, it is important that managers drawn to participation bear the chances and risks involved in capital investment. Comparable to a capital investment, the sale and purchase price of the managers’ co-investment should be at fair value. Tauser (2017) criticises this norm set by the fiscal court.

Furthermore, according to the current decision, typical vesting-clauses, which represent sales restrictions on co-investment participation by a manager, are acceptable as well. Such clauses are generally not contrary to the beneficial ownership of the managers in the interests in the co-investment vehicle (Tauser, 2017).

Hence, such programmes need not be completely compliant with the arm’s length principle (Poenicke and Buenning 2014). However, a careful implementation of the co-investment programme is necessary in order to avoid tax risks (see Section 4).

Typical Structure of Management Participation Programmes

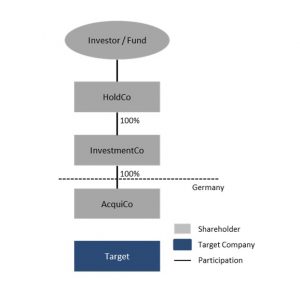

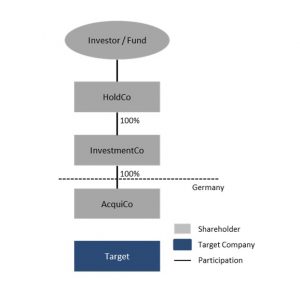

Financial investors, who invest in (here: German) target companies, typically have a multi-level acquisition structure (Bussian et. al., 2016). Such an acquisition structure can be simplified to look like the following structure, which will be especially helpful in understanding the next chart.

Fig. 1: Acquisition Structure of a Financial Investor with a future German Target Company (prior to signing the sale and purchase contract)

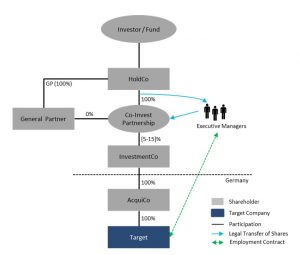

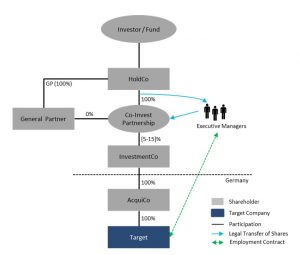

The participation by co-investors is typically bundled via a tax-transparent German (limited) partnership. The managers can participate in these investment vehicles, which are often organized in a BGB company (‘Gesellschaft buergerlichen Rechts’), a partnership organized under the German Civil Code, or in a limited partnership with a limited liability company as a general partner (‘GmbH & Co. KG’—descriptions of company types that follow ‘Co-Invest Partnerships’). Later, a legal form is given under the current practice. Furthermore, it will ensure that these vehicles will not qualify as commercial units, according to the German Trade Tax Act. This can be met by engaging a limited partner, who is entitled to be a managing limited partner of a Co-Invest Partnership (ITA, 2009).

These co-investments aim at indirect equity participation by co-investors in the target company employing top-line and second-line managers. These managers, who are also co-investors, will become limited partners in the Co-Invest Partnership. The managers generally acquire (indirectly) 5–15% of the share capital in the target (Roedding, 2017). The structure can be simplified and illustrated as follows:

Fig. 2: Typical Structure of Management Participation in a Co-Investment Vehicle (post signing the sale and purchase contract)

In this case, HoldCo has established the co-investment structure. Thus, HoldCo sells limited partnership interests in Co-Invest Partnership to the selected managers in consideration of cash. After the payment of the purchase prices, the managers will indirectly hold shares in the InvestmentCo.

Along with the signing of the sale and purchase agreement between a separate acquisition vehicle (‘AcquiCo’) and the seller, the HoldCo, InvestmentCo, the Co-Invest Partnership, enters into a co-investors’ and shareholders’ agreement with respect to their holding of shares in InvestmentCo. Such an agreement regulates the rights and obligations of all parties and helps to avoid future conflicts, for example, over the direction of business activities.

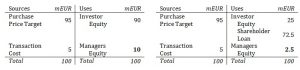

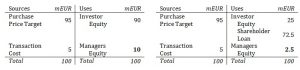

Such a structure links the executive managers in two respects to Target, which is also the primary interest of the investor. On the one hand, the managers enter into capital participation by way of contributing their own money to the investment vehicle, and, on the other, such equity participation leverages the managers’ participation in a partially credit-financed purchase by AcquiCo (Table. 1). For these reasons, the managers are incentivized to develop the business of Target in order to increase the refund value of their capital in the case of an exit by the investor.

Regarding the restrictions of the German Holding Companies Act (UBGG, 1998), the acquisition of Target in private equity transactions can be financed maximum with 3 portions (shareholder) loan and 1 portion equity (Bussian et. al., 2016). Such a finance structure leads to the fact that managers will only bear (here) 2.5% of the total equity, while holding 10% of share capital in InvestmentCo and indirectly in Target (Eilers et al., 2016).

Tab. 1: Incentive System by Debt-Financed Purchase—Consolidated Sources and Uses

The table illustrates that managers indirectly participating with 10% of the shares in Target need only to contribute one quarter to reach this ownership in case of debt-financing by the investor (see also Table 2).

Tax Considerations and Calculations

Based on the review, a careful structuring is required of the co-investment, especially the leaver scheme. The tax risks arising from an inappropriate structure have to be borne solely by the managers with regard to the transparent structure.

Tax risks can arise at three stages within the holding period—first, at the time of acquiring the interest in the investment vehicle; second, during the holding period; and, third, at the time of the disposal of the shares in the partnership. These three periods shall be considered from a German international tax perspective.

Preamble

Co-investors who are tax-resident in Germany are subject to unlimited German tax liability with their worldwide income, e.g. dividend income, interest income from loans, and capital gains. Investors who are tax-resident in Germany can be subjected to limited German tax liability with income earned in Germany such as capital income, depending on the type of financial instrument and other conditions.

(a) Tax considerations during the purchase of indirect interest in the Co-Invest Partnership

The sale and the transfer of limited partnership interests in the partnership by HoldCo to the managers should be tax neutral provided the transaction is based on fair market value. In case of a sweet equity contribution, taxation would arise at the level of a manager. According to the German comprehension, the sweet equity contribution would qualify as wage in the amount of the difference between the purchase price and the fair market value of these interests. The tax rate of wages can rise to 45% plus a solidarity surcharge.

In case of managers living abroad, the German target can be made liable to pay wage taxes as an indemnitor. The tax authorities qualify such wages as “wage by third parties”, based on Sec. 38 of the Income Tax Act (ITA, 2009). In tax audits, expenses towards the implementation of the co-investment structure (e.g. notary services, tax, and legal advice regarding statutes and the shareholder’s agreements, inter alia) are qualified as “wage by third parties” by the tax authorities. This currently causes considerable frictions in practice.

As a result, it is not necessary to check a double taxation treaty in this case. The target probably would have repayment claims.

(b) Tax considerations in the holding period of the interests in the Co-Invest Partnership

In this scenario, the managers can profit from their investment by way of dividend distribution along the shareholding chain. In this period, it is not common to partially realise capital gains from the disposal of shares because of vesting clauses. Bad leavers, too, touch their capital contribution only after the total sale of the shares.

Depending on the legal design of the programme, dividend distribution to the managers could also qualify as wages. This can have bad impacts on the manager, as it will be shown in the tax calculations at the time of exit.

(c) Tax considerations at the time of disposal of the interests in the Co-Invest Partnership

The most relevant taxable event is the sale of Target shares. Based on the typical drag-along-right in the agreement, managers are also obliged to sell their interests in case the investor wishes to realize the investment by way of an exit.

There are two levels at which the capital gain can be realized in case of a resale of the target.

The capital gains can be realized at the level of InvestmentCo, which is typically not resident in Germany. That means, from a German tax perspective, these capital gains upon disposal of at least 1% of the shares in AcquiCo would be subject to a limited German tax liability, according to the German Income Tax Act (ITA, 2009). However, Germany would not be entitled to tax such capital gains pursuant to Article 13, para. 5, of the OECD Model Tax Convention (OECD, 2014).

If, in contrast, AcquiCo sold all shares Target, 5% of any capital gain would be subject to German CIT and TT, resulting in an effective tax rate of approximately 1.5%. In addition, the capital gain would have to be distributed as dividend to its shareholders, inviting the German withholding tax.

Against this background, InvestmentCo should sell shares in AcquiCo in order to mitigate the exit tax burden because there is typically a participation exemption regime in the state of domicile of InvestmentCo that should be applicable at the level of InvestmentCo.

Capital gains from the disposal of shares in InvestmentCo realized by investors resident in Germany for tax purposes are:

- Subject to the final flat tax at a rate of 26.375%, if the investor holds its shares among its private assets and has a participation quota of less than 1%;

- Subject to the so-called part-income taxation regime, 40% of the capital gain is tax exempt, and the remainder is subject to progressive rates of up to 47.48%, if the investor has a participation quota of 1% or more;

- 95% tax exemption for CIT and TT purposes, if the investor is a German corporation.

According to the national law, this tax burden has also to be borne by non-German resident investors. If there is a double taxation treaty, comparable to the OECD Model Tax Convention (OECD, 2014), between Germany and the country of the manager’s residence, Germany will not have the right to tax these capital gains.

In that case, these capital gains will be treated as wage, where Article 15, para. 1 and 2, of the OECD Model Tax Convention (OECD, 2014) can be relevant. Non-German resident managers employed by Target and stationed periodically at its headquarters would be subject to German taxation only to the extent that Target has borne the wages. That means the capital gains realized by non-resident managers would be subject to limited taxation according to a German international tax convention. As a consequence, these capital gains will be taxed as wages with the proportional tax rates up to 47.48% (taxable income in the amount of EUR 256,000).

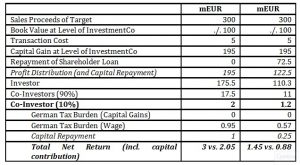

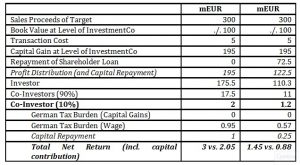

The following table will illustrate the tax impacts for managers whose capital gains qualify to be (i) capital gain and (ii) as wage. In this example, Target is sold at a multiple of three and the manager, who is not resident in Germany, holds participation to the extent of 10% of the interests in the Co-Invest Partnership.

Tab. 2: Profit Determination and Taxation Depending on Qualification of Income from Co-Investment Programme

Within this realistic scenario, a manager, who has participated with 10% in a managing participation programme, will have a total net return to the amount of EUR 3 million (scenario: equity funding by investor) and EUR 1.45 million (scenario: debt and equity funding by investor) in case the capital gain is qualified as a capital income. Germany would not tax this capital gain in case the investor is resident in a contracting state. In contrast, if the co-investment programme is closely linked to employment relationship of the relevant manager, the total net return of these investments amounts to EUR 2.05 million (scenario: equity funding by investor) respectively EUR 0.88 million (scenario: debt and equity funding by investor) . Thus, the capital gain is considered as wage from the German tax perspective. That would reduce the capital return compared to the initial investments about almost 100% (scenario: equity funding by investor) and 160% (scenario: debt and equity funding by investor).

Incidentally, this example also shows the leverage effect in case of a partially debt-financed purchase of Target (see also Tab. 1).

Conclusions

Co-Investment Programmes are a common vehicle in transactions to keep relevant managers on board. As part of their incentive, these managers can profit from a separate capital contribution to the investment vehicle, where they indirectly participate in the company’s business success. In case of a debt-finance purchase of Target company, the managers can extraordinarily profit by participating in such a programme.

According to the current decision of the Federal Fiscal Court (BFH, 2016b), leaver schedules can be agreed without endanger tax treatment of a programme. It is to be hoped that the fiscal authorities will accept that decision and apply that principle beyond the individual case of the decision. Nonetheless, the fiscal authorities have—especially in tax audits—a critical view on such programmes (Roedding, 2017). Leaver schedules are an important aspect of such programmes for the designing of fair conditions. From the economic perspective of an investor, a bad leaver should not profit from corporate development in the same way as a good leaver does. So, co-investment programmes are basically no tax-driven considerations of the investor (Thiele, 2017).

In case of fiscal treatment of the management participation programme, the consolidated overview of the individual agreed conditions in the programme is significant. For this reason, co-investment programmes need to be implemented very carefully with regard to the strict attitude of the tax authorities. It should be ensured that the following fundamentals will be met in management participation programmes:

First, the management participation programme must be a special contract next to the employment contract. Moreover, it is necessary that the co-investment is purchased at a fair value by all managers who participate. In addition, the managers should also bear all risks and chances resulting from that investment. That means they will have to hold the beneficial ownership of the interests by way of voting and profit participation rights. In case the Target is hit by economic difficulties, managers must implement restructuring measures compared to shareholders.

In contrast, besides leaver schemes, it is also not directly harmful from a German tax perspective, if only a special group of managers are able to participate in such a programme and there are restrictions on the disposal of the interests through the managers.

In case of implementing co-investment programmes without considering tax restrictions, the employment contract can overlap the co-investment capital investment. Consequently, all distributions to the managers (e.g. dividends, capital gains) will be considered as wages. Managers, irrespective of whether they are German or non-German-residents, will be subject to (un)limited tax liability in Germany. In case of double taxation treaties, German authorities would carry out their right to taxation based on Article 15 of the OECD Model Tax Convention (OECD, 2014). If there is no double taxation treaty between Germany and the state of manager’s residence, Germany would execute its right to taxation based on the national income tax law (ITA, 2009). Therefore, in case of a requalification of capital gain to wage, a manager would bear a German tax burden of up to 47.48% compared to a tax burden of 0%. On behalf of the relevant managers, the investors should carefully implement a co-investment structure with target assets based on the tax restrictions.

References

Bundesfinanzhof (BFH)/ Federal Fiscal Court Decision of 23 June 2005, Reference VI R 10/03, BStBl. 2005 II, p. 770.

Bundesfinanzhof (BFH)/ Federal Fiscal Court Decision of 4 May 2006, Reference VI R 28/05, BStBl. 2006 II, p. 781.

Bundesfinanzhof (BFH)/ Federal Fiscal Court Decision of 19 June 2008, Reference VI R 4/05, BStBl II 2008, p 826.

Bundesfinanzhof (BFH)/ Federal Fiscal Court Decision of 17 June 2009, Reference VI R 69/06, BStBl. 2010 II, p 69.

Bundesfinanzhof (BFH)/ Federal Fiscal Court Decision of 20 May 2010, Reference VI R 12/08, BStBl II 2010, p. 1069.

Bundesfinanzhof (BFH)/ Federal Fiscal Court Decision of 5 November 2013, Reference VIII R 20/11, BStBl II 2014, p. 275.

Bundesfinanzhof (BFH)/ Federal Fiscal Court Decision of 21 October 2014, Reference VIII R 44/11, BStBl. 2015 II, p. 593.

Bundesfinanzhof (BFH)/ Federal Fiscal Court Decision of 1 September 2016 (2016a), Reference VI R 67/14, BStBl II 2017, p. 69.

Bundesfinanzhof (BFH)/ Federal Fiscal Court Decision of 4 October 2016 (2016b), Reference IX R 43/15, ZIP 2017, p. 609.

Bussian, A.; Stiegler, T.; Schmid, J. (2016), ‘Implications of Regulations and Taxes on Inbound Invetments in Alternative Asset Classes in Germany,’Proceedings of the 28th International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA), ISBN: 978-0-9860419-8-3, 9-10 November 2016, Seville, Spain, pp. 1262-1273.

Cooke, W.N. (1994), ‘Employee Participation Programs, Group-Based Incentives, and Company Performance: a Union-Nonunion Comparsion,’ Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 47 (4), pp. 594-609.

Eilers, S.; Roedding, A.; Schmalenbach, D. (2016), Unternehmensfinanzierung, 2nd edition, C.H.BECK, Munich.

Finanzgericht (FG)/ Fiscal Court of Cologne of 20 May 2015, Reference 3 K 3253/11,ECLI:DE:FGK:2015:0520.3K3253.11.00.

Koch-Schulte, B. (2015), ‘Steuergünstige Gestaltung von Mitarbeiterbeteiligungen im Management-Buy-Out Strukturen,’ Der Betrieb, 2015 (38), pp. 2166-2170.

Hohaus, B. and Inhester, M. (2003), ‘Rahmenbedingungen von Management-Beteiligungen,’ Deutsches Steuerrecht, 41 (41), pp. 1765-1768.

Income Tax Act/ Einkommensteuergesetz of 8 October 2009, BGBl. I p. 3366, 3862, last amended by law of 23 December 2016, BGBl. I p. 3191.

OECD Model Tax Convention (2014) of 30 October 2015 on Income and on Capital.

Poenicke, A. and Buenning, M. (2014), ‘Aktuelles zu Managementbeteiligungen – insbesondere in der Form von Unterbeteiligungen,’ Betriebsberater, 2014 (45), pp. 2717-2721..

Roedding, A. (2017), ‘Endlich: „Leaver-Regelungen“ bei Management-Beteiligungsprogrammen führen nicht zu Einkünften aus nichtselbstaendiger Arbeit,’ Deutsches Steuerrecht, 2017 (08), pp. 437-439.

Schulte, N. (2016), ‘Vermögenssicherung durch Diversifizierung,’ Zeitschrift für Familienunternehmen und Stiftungen, 2016 (05), pp. 154-158.

Thiele, P. (2017), ‘Aktuelle Entwicklungen bei der steuerlichen Behandlung von Managementbeteiligungen,’ Betriebsberater, 2017 (18), pp. 983-986.

UBGG/ Gesetz ueber Unternehmensbeteiligungen, Bundesgesetzblatt Teil I as of 09.09.1998, p. 2765, last amended by Act of 28.08.2013, Bundesgesetzblatt Teil 1, p. 3395.

Von Braunschweig, P. (1998), ‘Steuergünstige Gestaltung von Mitarbeiterbeteiligungen im Management-Buy-Out Strukturen,’ Der Betrieb, 1998 (37), pp. 1831-1837.