Literature Review

Back in 2004, Milne concluded that the EU trading model was outmoded compared to trading model outside EU, therefore after Brexit, UK might have similar benefits as it had as a EU member, but with fewer costs. Pain and Young (2004) came to a conclusion that there is no reason to suppose Brexit would determine a significant rise of UK unemployment, but the level of UK economy output would be with 2.5% permanentely lower compared with EU membership. Oliver (2013) considered that both UK and EU would have to manage a series of internal changes and reforms and to cooperate for security in Europe and in the world. In the opinion of Möller and Oliver (2014), even as a EU member, often, UK was on the sidelines of the EU politics and this situation would lead either to UK leaving EU or EU leaving UK behind. Lyons (2014) highlighted that for UK leaving EU and after Brexit having good economic relation with EU and with the rest of the world, would be better than remaining in a union that does not reform. Oliver (2015) showed a more pragmatic vision, considering that when joined EU (former EEC) in 1973, EU was seen as a prosperous economic future, but now UK considers EU in declines and moves towards a multipolar world outside EU. The think-tank Open Europe estimated the costs of EU regulations at £33.3bn a year in 2014 and the benefits at £58.6bn a year. It was also concluded that the Norway scenario would mean leaving an economic union to join another union with the same costly rules. Therefore, it was concluded the Norway or the Swiss model are not suitable for UK and that the economic impact of Brexit is not as clear as the other researches suggested. In the same year, 2015, the German think-tank Bertelsmann Stiftung came to a conclusion that Brexit will increase trade costs between UK and EU and decrease trade activities. In 2016, HM Government released two analysis regarding the impact of Brexit, one focused on short time economic impact and, highlighted the uncertainty and instability on financial markets and the other one focused on long time economic impact, assesing the consequences of Brexit on long term on GDP, productivity and FDI. Koenig (2016) analyzed the EU foreign affair and security policy after Brexit, as well as future possible EU-UK cooperation scenarios regarding security policy. The Brexit impact on devolution and foreign affairs of UK regions was studied by Whitman (2017) and the Brexit impact on EU political establisment was studied by Hobolt (2016). Several research papers focused on the impact of Brexit on human rights, Mindus (2016) investigated the impact of losing the EU citizenship after Brexit, specially on second country nationals in UK and their families, while Douglas-Scott (2016) tried to find out to what extent the ‘acquired rights’ would remain valid for millions of individuals as well as for their children and their grandchildren. Guild (2017) detailed the administrative hurdles which EU citizens who will remain in UK after Brexit will have to face. Other researchers focused on the Brexit impact on Nothern Ireland (Tonge, 2016), Gormley-Heenan (2017), on Scotland, Wales and Nothern Ireland (Birrell and Gray, 2017). Regarding the economic impact of Brexit, there are divergent opinions, from the Brexit economic shock to Brexit might lead to a better economic outlook.Ottavio et al. (Centre for Economic Performance, 2014) proved that Brexit will impose significant costs for UK economy, and the losses will be between 9.5% and 2.2% of GDP, depending on the Brexit scenario. Busch and Matthes (2016) concluded that UK have to face greater risks than EU and in the most pessimistic scenario, there will be a 10% loss in the long run; a conclusion that is consistent with the one from RAND analysis (2017) that UK economy will be affected in most Brexit scenarios. Although admitting that after Brexit there will be a certain degree of uncertainity, Mansfield (2014) was confident that on the long run, UK might have a good economic outlook outside EU. Shroeter and Nemeczek (2016) considered that Brexit will not significally affect UK economy, if UK will still be a EEA member, while Owen, Shepheard and Stojanovic (2017) investigated the necessary future arrangements if UK will leave the Custom Union as well. A conexed study presenting the framework of the Brexit transitional process was conducted in 2017 by Frantziou and Lazowski.

Before Brexit- the EU-UK trade-from UK point of view

According to HM Government analysis, the overall net benefit of EU membership for UK was 4-5% of GDP, which means £73bn‐91bn per annum or 2,700‐£3,300 per household (in 2014 GDP), also EU membership increased goods trade between UK and other EU members by 55%; meaning £130 bn (in 2013 GDP).

UK accounts for one sixth of EU exports, 12.6% of UK GDP depends on UK-EU trade and the UK trade deficit has grown steadily to £6.9 billion in 2017. The UK is currently the second largest net contributor to the operating budget of the EU in absolute terms, behind Germany, and the fourth largest as a percent of GNI, behind Sweden, Denmark and Germany.

UK is both a major exporter of services, mainly financial services to the world and a gateway to EU for service industries, specially, financial services of the world. Half of all European headquarters of non-EU firms are in the UK and UK is hosting more headquarters than Germany, France, Switzerland and the Netherlands put together. The service sector is the most important for UK economy, accounting for 80% of GDP. Trade in services accounts for almost half of the total exports (43%) and a quarter of the total imports. For over 5000 UK banks, investment firms, insurance companies, maintaining the pass porting rights after Brexit is vital to operate freely in EU. Financial services account for about one third of UK total services and for two thirds of overall services surplus. In 2016, the financial sector accounted for 7.2% of UK gross value added and for 3.1 % of all UK jobs. In the most unfavorable Brexit scenario, a 5% loos of the financial sector is anticipated. Over one million jobs in the financial services sector and 285,000 jobs linked to this sector are at risk because of Brexit. Other major services are sales, maintenance and repair of motor vehicles, renting of machinery and equipment and health and social care.

The chemicals are among the most important UK exports to EU. In the worst Brexit scenario, a loss of 11%, almost the same in added value and an increase of 4.5% of export price. Chemicals, automotive industry and transport equipment would face the highest bound tariffs in the worst Brexit scenario.

EU accounts for 60% of UK agri-food exports and UK imports half of its food. In the worst Brexit scenario, tariffs of 30-40% would be applied to wine and cheese, tariffs of 30-70% would be applied to meat (depending on the type of meat), tariffs of 36% on dairy, tariffs of 30% on sheep exports and tariffs of 50% on beef exports.

Pan-European collaboration for UK researchers under the program Horizon 2020, funded from the European Research Council (UK received more than any other EU member), future cooperation with the European Space Agency (especially in Galileo project) and studying in UK universities (especially through Erasmus + program) are at risk because of Brexit. More than any other country and 50% more than Germany, allowing UK universities to fund more than 10% of the research projects from EU contributions.

Within UK, 40% of Wales exports go to EU, and 200,000 jobs are related to Wales exports. Under CAP, Wales received £250m a year for direct payments and £665m in the current round for rural development [1]. For Nothern Ireland, Brexit will put an end EURO 3.5bn in farm subsidies and structural grants [2]. According to Scottish government study, Brexit will put the damage at £11bn a year and the dent in Scottish public finances at £3.7bn and 80,000 job losses [3].

Before Brexit- the EU-UK trade-from EU point of view

According to HM Government, less than 8% of EU exports goes to UK and only 3.1% of the EU GDP (excluding UK) on exports goes to UK. EU (excluding UK) accounts for 44% of UK exports and for 54% of UK imports. The most important markets for UK goods exports are: Germany, France, Netherlands and Ireland and the main exporters to UK are Germany, Netherlands and France. UK is a major exporter to Ireland, Cyprus, Malta, Netherlands and Belgium. Ireland exports more than one tenth of its goods to UK and 14 other EU countries exports more than 5% of their goods to UK, therefore Ireland, Luxembourg, Belgium, Germany, Sweden, Malta and Cyprus will suffer more due to Brexit. The trade surplus in relation with UK represents more than 1% of the GDP of Netherlands, Poland, Czech Republic, Belgium, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovenia. Within EU members, there is a wide diversity regarding the trade with UK.

For Germany, the value of exports to UK was €78bn and the value of UK imports was €50bn in 2013. Germany would lose about €8.7 billion in best Brexit scenario, meaning €100 per capita and €58 billion in worst Brexit scenario, meaning €700 per capita (at GDP 2014 level). Germany has a trade surplus equivalent of 1% of its GDP (at 2013 level). Major German banks (Deutsche Bank) operates in London.

The Netherlands exported €42bn in goods and €7bn in services in 2013, running a surplus of €6.8bn. ING and other major Dutch banks operate in UK. Major Dutch companies which have headquarters in London (Unilever) are incorporated in UK (Royal Dutch Shell) and operate in UK (Philipps).

Ireland exported to UK more than any other EU member, equivalent to 12% of its GDP and is also the country with the highest trade deficit with UK. Many international banks and hedge funds have close links both with Dublin and with London.

Cyprus exported the equivalent of 7% of its GDP (at 2013 level) mainly in services, while Sweden exported the equivalent of 2.5% of its GDP (at 2013 level), both countries have solid links with UK financial service sector and have a small trade deficit with UK.

Belgium has one of the largest trade surplus; equivalent to 1.8% of its GDP (at 2013 level) and strong trade links with UK. Spain has a trade surplus due to tourism services exports.

France exports to UK were equivalent to 2% of its GDP (at 2013 level) and have strong financial links with UK. Poland has a trade surplus equal to 1.3% of its GDP (at 2013 level) and the exports value to UK was about 2.8% of its GDP (at 2013 level). Italy has a trade surplus of more than €5bn, yet its exports to UK are not as important as for the above mentioned countries.

The Brexit impact for Romania would be a moderate one, considering the limited level of bilateral trade between Romania and the UK but it protects the rights of its citizens already living in UK.

FDI in UK before Brexit

Although the stock of EU FDI in UK has fallen from €38.9 bn in 2011 to €21.7 bn in 2015, they are still higher compared to North America or Asia. As EU membership, the FDI flows to UK increased by 28% and the FDI inward stocks by 34%.

The Sweden FDI is in energy sector, the Belgium FDI is in wind farms, the German FDI is in transportation and storage sector. Spanish firms operate on four major airports in UK, the Spanish FDI in UK is similar in scale with the German ones. French FDI in UK, second after Netherlands as total value, focuses mainly on infrastructure projects. Belgium is the fourth most important UK trading partner and especially the Flemish north which accounts for the majority of Belgian exports to the UK together with Netherlands, Luxembourg and Estonia who have large FDI positions in the UK and therefore it has the incentives to see the UK get the best Brexit deal possible [4].

Migration flows before Brexit

Based on Article 45 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, European citizens have the right to work in another EU country without needing work permission; reside there, stay there after employment has finished, enjoy equal treatment with other nationals in addition to working conditions and all other social and tax advantages.

For EU, the two principles, the freedom of trade and the freedom of movement, are mutually inclusive. For UK, as much freedom of trade as possible and as less freedom of movement as possible would be preferred. At this moment, about 3.3 million of European citizen live in UK and about 1.2 million of British citizen live in EU [5].

From UK point of view, there has been an increase in cheap labor migration to UK claiming free benefits, but it has a very low contribution to UK economy and increases national unemployment. Therefore, UK officials want a limit on net migration under a work permission scheme [6]. 63% of CBI (Confederation of British Industries) admitted that the free movement was beneficial for their business.

Brexit would have direct effects on countries like Poland, which is a major source of immigration and indirect effects on other countries, as Spain, which became home for many British retirees.

Among the EU citizens living in UK, the biggest group is of 850,000 Poles, most of them are young, skilled and economically active, the second foreign nationals are 329,000 Irish, but there are also 200,000 Lithuanians,75,000 Slovaks, 200,000 Bulgarians and 223,000 Romanians. The equivalent of one third of Cyprus populations (300,000) is living in UK as Cypriot descendent. The number of French people living in UK is similar with the number of British people living in France (150,000), while the number of Spanish people living in UK (90,000) is as nine times smaller than the number of British people living in Spain.

UK think tank Institute for Public Policy Research argued estimating that the UK economy would need more than 200,000 migrants a year to avoid the ‘catastrophic economic consequences’ of Brexit due to low productivity, ageing population and shortage of labor in key areas, such as the social care. The Construction Industry Training Board has estimated that 36,000 new workers a year will be needed to cover even current levels of demand. The UK Commission for Employment and Skills estimated that the social care will need over a half of a million of extra workers by 2022. UK needs a total of 47,000 migrant workers a year [7].

The main Brexit issues of negotiations are: the transition agreement, the payment for leaving EU, FTA EU27-UK and the free movement agreement. The other issues of negotiation are as follows:

- Military basis-: at the currently Sovereign Base Areas of Akrotiri and Dhekelia, there is a complex mix of UK, Cypriot and EU rules and jurisdictions and after Brexit, the border between the bases and the Cypriot territory will constitute an external border of the EU.

- Rights of citizens-: including the right to continue residence, including permanent residence after five years, the coordination of social security systems and export of benefits, the right of self-employment and access to the labor market including education and training for family members under the same conditions as nationals.

- The stability based on the Good Friday Agreement-: public statements, by the UK government and from the EU-27, reveal a strong and repeated commitment to uphold the Good Friday Agreement in all its parts. This means maintaining as much of the status quo as possible in terms, for example, of the free movement of goods, services, capital and people and ensuring that every effort is made to avoid any hardening of the border [8].

- The jurisdiction of European Court of Justice-: the UK, the government stated that ECJ jurisdiction will come to an end when the transitional process comes to an end and the rights of EU citizens living in the UK after Brexit will only be subject to the British law.

- Euratom-: the EU negotiating directives specify that the exit agreement must include provisions for the transfer of ‘special fissile material’ from Euratom facilities in the UK and also the transfer of facilities

- Gibraltar-: after the United Kingdom leaves the Union, no agreement between the EU and the United Kingdom may apply to the territory of Gibraltar without the agreement between the Kingdom of Spain and the United Kingdom.

- The National Agency for Erasmus+ in the UK-: a partnership between the British Council and Ecorys UK remains wholly committed to the Erasmus+ program and its benefits. The National Agency strongly supports continued full membership of the program for the UK through to 2020 as planned.

Divergent interests on issues of negotiations within EU

EU northern countries with Germany as the largest member consisting of 12 countries committed to the free movement of goods and people would target the maximum possible freedom of goods, to lure as much as possible of the UK financial industry to their countries. Some northern Europeans, notably Finland, Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia, along with Poland, care a lot about maintaining security cooperation with the UK to fend off potential threats from Russia.

Southern European countries comprise only seven countries, but among these are France, Italy and Spain with the maximum possibility of leaving payment and preserving agricultural and fisheries policies. Spain and Malta, in particular, will be interested in ensuring British retirees to remain invested in their tourism and real estate markets and Cyprus will be concerned with tourism as well as arrangements regarding UK military bases, which cover 1 per cent of its land.

The Eastern countries, the Visegrad Group (the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia) along with Bulgaria, Croatia, Slovenia and Romania, will strive for strong protection for their citizens currently living in UK.

Game theory model might help to analyze Brexit

Let’s assume the players are UK and EU; both of them are united entities, despite the divergent interests discussed above and despite that within UK, Scotland, Northern Ireland, Greater London and some South West regions which voted differently at the referendum than Wales and the other regions of England, and ironically, the regions of UK which voted massively for Brexit are the most vulnerable to losses.

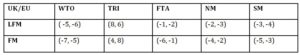

The strategies of EU for UK would be: WTO-WTO status, TRI-trilateral agreement (EU-UK-US), FTA-EU-UK FTA, NM-Norway model and SM-Swiss model. The strategies of UK for EU would be: FM-freedom of movement and LFM-limited freedom of movement. The payoffs are based on the GDP losses for UK and EU from the previous studies. In each pair, the first number is for UK and the second number is for EU. The payoffs matrix would look like this:

Table 1: The Payoffs Matrix

Source: Author’s table, based on own research

Of course, the best scenario from the matrix seems to be TRI; a trilateral agreement UK-EU-US, all of the previuos researches agree that it is the only scenario in which the GDP of UK, EU, US are growing comparing with the situation when UK was a EU-member, in this scenario EU GDP would be twice of UK GDP and US GDP the sum as the other two. But, this trilateral agreement would take years to be signed and ratificated, not to mention a third player who will join negociations, so we may think on it as the long-term solution. If in the future trilateral agreement, US chooses limited freedom of movement, as it did until now, UK would gain more, but if US would choose the freedom of movement, EU would gain more. The worst case scenario would be WTO-when the trade UK-EU would be under the WTO rules, both UK and EU will lose comparing to pre-Brexit status. Again, if the limited freedom of movement is agreed, UK would lose more than EU. Second best scenario would be FTA, which of course, is worse than pre-Brexit status, so both UK and EU would suffer losses of their GDP, therefore, who would lose more depends on the freedom of movement which would depend on the political determination regarding this issue. Norway Model and Swiss Model come in between FTA and WTO . And maybe the other two issues; the jurisdiction of ECJ and the leaving payment, will depend on the outcome of the negociations, on the freedom of trade and on the freedom of movement. The oher issues of negociation would probably use a win-win strategy.

Conclusions

The Brexit negotiation is a very complex process in which neither of the players can not stick to initial positions. On short term, there will be definitly a limited freedom of trade, because a non EU-member can not have the same rights as a EU-member, otherwise EU would be at risk. The status of EU citizen living in UK before Brexit would be most likely preserved though some aquired rights which might change over time. It seems that the freedom of movement would be the toughest issue. The analysis of the pre-Brexit economic situation showed profound, complex and historical connections between UK and other EU countries. The matrix of payoffs revealed the best scenario, the second best and the worst scenario as well. The best scenario from the matrix is a trilateral agreement UK-EU-US, this is the only scenario in which the GDP of UK, EU, US are growing comparing with the situation when UK was a EU-member, but this could be only a long-term solution. Second best scenario would be FTA which is worse than pre-Brexit status. The worst case scenario would be WTO. In this case, both UK and EU will lose comparing to pre-Brexit status. The limitation of the model lies in the initial assumptions, to consider both UK and EU as united entities. Another limitation is that the level of security will not esentially change as the global threats could be under control. There is, of course, another possible scenario; UK to rejoin EU which seems almost improbable, UK prim-minister said a coming back is imposible, the European Council presisently said that-the EU door will be opened for UK and lord Kerr, who actually wrote Article 50 of the Treaty and said one can change his/hers mind while the process is going. One thing is for sure, Brexit broke an international equilibrum and it would be in everyone’s best interest to reach another equilibrum. The limitation of the study is considering the economic and security reasons of UK and EU as prevailing over any other reason. After UK will eventually leaves EU in 2019, assuming no delay, future research will be conducted to assess the Brexit outcome, comparing with the forecasting of the current analysis.

Endnotes

[1]. Public Policy Institute for Wales (2016), ‘What will Brexit mean for Wales?’. [Online] [Retrieved July 28, 2016], http://ppiw.org.uk/what-will-brexit-mean-for-wales

[2]. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/0/how-would-brexit-affect-northern-ireland-and-scotland/

[3]. https://www.theguardian.com/politics/audio/…/scotlands-future-brexit-means-podcast

[4]. Irwin, G. (2015, June), ‘BREXIT: the impact on the UK and the EU’, Global Counsel.

[5]. Exton, G. (2016), ‘Brexit and game theory: A single case analysis’, MERICI, volume 2, 2016.

[6]. Maneesha, Vijai, N. and Singh, A. (2016), ‘To Develop a Game Theory Model Analyzing the Negotiations between Britain and European Union’, Proceedings of the Fourth Middle East Conference on Global Business, Economics, Finance and Social Sciences (ME16Dubai May Conference) ISBN: 978-1-943579-30-3 Dubai-UAE, 13-15 May, 2016.

[7]. http://ourglobalfuture.com

[8]. Eriksson, E., Phinnemore, D. and Hayward, K. (2017, November), ‘UK Withdrawal (‘Brexit’) and the Good Friday Agreement; Constitutional Affairs’, Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs; Directorate General for Internal Policies of the Union; PE 596.826.

References

- Birrell, D. and Gray, A.M., (2017), ‘Devolution: The Social, Political and Policy Implications of Brexit for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland’, Journal of Social Policy, 46 (4), 765-782.

- Busch, B. and Matthes, J. (2016, April 8), ‘Brexit – The Economic Impact; A Meta-Analysis’, IW Report 10/2016, Cologne Institute for Economic Research.

- Centre for Economic Performance, (2014), ‘Brexit or Fixit? The Trade and Welfare Effects of Leaving the European Union’, CEP Policy Analysis.

- Douglas-Scott, S. (2016), ‘What Happens to ‘Acquired Rights’ in the Event of a Brexit?’, UK Constitutional Law Association. [Online] [Retrieved May 16, 2016], https://ukconstitutionallaw.org/2016/05/16/sionaidh-douglas-scott-what-happens-to-acquired-rights-in-the-event-of-a-brexit

- Eriksson, E., Phinnemore, D. and Hayward, K. (2017, November), ‘UK Withdrawal (‘Brexit’) and the Good Friday Agreement; Constitutional Affairs’, Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs; Directorate General for Internal Policies of the Union; PE 596.826.

- Exton, G. (2016), ‘Brexit and game theory: A single case analysis’, MERICI, volume 2, 2016.

- Frantziou, E. and Łazowski, A. (2017), ‘Brexit Transitional Period: The solution is Article 50’, CEPS. [Online] [Retrieved September 9, 2017], https://www.ceps.eu/publications/brexit-transitional-period-solution-article-50

- Gormley-Heenan, C. and Aughey, A. (2017), ‘Northern Ireland and Brexit: Three effects on ‘the border in the mind’’, The British Journal of Politics and International Relations. [Online] [Retrieved June 8, 2017], http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1369148117711060

- Guild, E. (2017), ‘Brexit and the Treatment of EU Citizens by the UK Home Office’, CEPS. [Online] [Retrieved September 4, 2017], https://www.ceps.eu/publications/brexit-and-treatment-eu-citizens-uk-home-office

- HM Government, (2016, April), ‘HM Treasury analysis: the long-term economic impact of EU membership and the alternatives’, Cm 9250.

- HM Government, (2016, May), ‘HM Treasury analysis: the immediate economic impact of leaving the EU’, Cm 9292.

- Hobolt, S.B. (2016), ‘The Brexit vote: a divided nation, a divided continent’, Journal of European Public Policy, 23 (9), 1259-1277.

- Irwin, G. (2015, June), ‘BREXIT: the impact on the UK and the EU’, Global Counsel.

- Koenig, N. (2016, November 22), ‘EU External Action and Brexit: Relaunch and Reconnect’, Policy Paper 178, Jacques Delors Institut, Berlin.

- Lyons, G. (2014), ‘The Europe Report: A Win-Win Situation’, London City Hall. [Online] [Retrieved August 6, 2014], https://www.london.gov.uk/business-and-economy-publications/europe-report-win-win-situation

- Maneesha, Vijai, N. and Singh, A. (2016), ‘To Develop a Game Theory Model Analyzing the Negotiations between Britain and European Union’, Proceedings of the Fourth Middle East Conference on Global Business, Economics, Finance and Social Sciences (ME16Dubai May Conference), ISBN: 978-1-943579-30-3, Dubai-UAE, 13-15 May, 2016.

- Mansfield, I. (2014), ‘The IEA Brexit Prize: A Blueprint for Britain – Openness not Isolation’, Institute of Economic Affairs. [Online] [Retrieved April 9, 2014], https://iea.org.uk/publications/research/the-iea-brexit-prize-a-blueprint-for-britain-openness-not-isolation

- Milne, I. (2004, July), ‘A Cost Too Far? An analysis of the net economic costs & benefits for the UK of EU membership’, Civitas: Institute for the Study of Civil Society London.

- Mindus, P. (2017), European Citizenship after Brexit; Freedom of Movement and Rights of Residence, Palgrave Macmillan.

- Möller, A. and Oliver, T. (2014, September), ‘The United Kingdom and the European Union: What would a “Brexit” mean for the EU and other States around the World?’, The German Concil on Foreign Relations (DGAP) Analyse, No. 6.

- Oliver, T. (2013, September), ‘Europe without Britain; Assessing the Impact on the European Union of a British Withdrawal’, SWP Research Paper, German Institute for International and Security Affairs, RR 7, Berlin.

- Oliver, T. (2015), ‘To be or not to be in Europe: is that the question? Britain’s European question and an in/out referendum’, International Affairs, 91 (1), 77-91.

- Owen, J., Shepheard, M. and Stojanovic, A. (2017), ‘Implementing Brexit: Customs’, IFG Analysis/Implementing Brexit, Institute for Government.

- Pain, N. and Young, G. (2004), ‘The macroeconomic impact of UK withdrawal from the EU’, Economic Modelling, 21, 387-408.

- Public Policy Institute for Wales (2016), ‘What will Brexit mean for Wales?’. [Online] [Retrieved July 28, 2016], http://ppiw.org.uk/what-will-brexit-mean-for-wales

- RAND Corporation (2017), ‘UK Likely to Be Economically Worse-Off Outside the EU Under Most Plausible Trade Scenarios’. [Online] [Retrieved December 12, 2017], https://www.rand.org/news/press/2017/12/12.html

- Shroeter, U. and Nemeczek, H. (2016), ‘The (Unclear) Impact of Brexit on the United Kingdom’s Membership in the European Economic Area’, European Business Law Review, 27 (7), 921-958.

- Tonge, J. (2016), ‘The Impact of withdrawal from the European Union upon Northern Ireland’, University of Liverpool.

- Whitman, R. G. (2017, February), ‘Devolved External Affairs: The Impact of Brexit’, Research Paper, Europe Programme.

http://ourglobalfuture.com

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/0/how-would-brexit-affect-northern-ireland-and-scotland/

https://www.theguardian.com/politics/audio/…/scotlands-future-brexit-means-podcast