Introduction

To provide a clear picture of the progress in the external public audit process in Albania and Romania, it is very important to emphasize that the activity reports of National Audit Institutions have an important role in the use of public funds. Why do reports matter? The reports consist of statistical data and information on the material evidence of the evolution of external public audit process. Therefore, keeping a database for a particular process – such as external public audit – is not only a legal obligation, but also serves as a basis for informing researchers and practitioners who need to understand how the audit process was conducted.

The main purpose of the study is to diagnose the current state of external public audit in Romania and Albania by analyzing how audit contributes to a rule of law. This paper is based on a comparative approach between the annual activity reports of the institutions responsible for public external audit – the Romanian Court of Accounts (RCA) and the Supreme Audit Institution of Albania (ALSAI) – to highlight the similarities and differences in the way these institutions fulfill their constitutional mandate. The countries selected for analysis are chosen within a geographic region to identify the main similar historical and economic transition objectives. Regarding the activity of the external public audit, starting from the 26th of June 2003, there is a cooperation agreement between the two authorities and an Action Plan for the exchange of experiences, manuals, procedures and conduct of a joint performance audit during 2018 – 2020.

This paper aims at emphasizing the value and importance of today’s external public audit in the two countries, and at the same time, providing data to other researchers for in-depth studies in this field. Thus, the study will begin with reviewing the specialized literature on the importance of external public audit and then it will focus on ALSAI and RCA.

Review of specialized literature

The audit process is improved and perfected continuously and the recipients of this service feel this transformation day after day. The New Public Management and the Audit Society theory explains very well the evolution of audit institutions and the expansion of audit activities , but the specialized literature on public sector auditing outside the predominance of Anglo-American and North-European researchers (Bonollo, 2019) especially in Africa, Asia and Latin America, is limited (Johnsen, 2019). Among the most important studies that accentuate the importance and the differences of the SAIs , this paper mentions the analyses carried out by Pollitt et al. (1997, 1999, 2003), González et al. (2008, 2013), Pierre & Licht (2019), Clark et al. (2007), Klarskov Jeppesen et al. (2017), Jansons & Rivza (2017), Van Acker & Bouckaert (2019), Cornelia (2012), Jantz et al. (2015), Bonollo (2019), Peci & Rudloff Pulgar (2018), Bringselius (2018), Zuccolotto & Teixeira (2014), etc.

The specialized scientific literature on comparisons between the activities of the RCA (Oțetea et al., 2015; Pintea & Achim, 2009) and ALSAI, is relatively scarce. The Government of Romania contributes with more than 50% to total R&D expenditure, but the number of scientific research staff decreased through retirement, poor financial motivation, low salaries for junior researchers and elimination of doctoral benefits for all employees (Avram et al. 2014). Albania is at an early stage in the field of science and research, and the share of the public spending for scientific research in 2018 reached just 0.06% of the Gross Domestic Product (European Commission, 2019).

The comparative study on SAIs of Great Britain and Romania performed by Oțetea et al. (2015), results that the relationship between the RCA and the Parliament is quite low, as the Committee on Budgets, Finance and Banking in both Houses of Parliament analyzes the periodic accounts of the Court’s budget execution. Another study on the activity of the SAI including Albania and Romania, was developed by the OECD (2017). Compared with Romania, where the Parliament does not pay attention to the mechanisms necessary for the implementation of RCA recommendations, the Albanian Parliament pays greater attention to the implementation of the recommendations, but the stimulation and monitoring of these aspects have not been effective. In connection with the draft budgets, RCA reports are not regularly used as input by parliamentarians for the annual debate, while ALSAI reports are regularly relied on as input. ALSAI does not carefully follow the recovery of damages caused to the state budget as a result of deviations committed, no matter how the investigations are concluded. In most cases, criminal court decisions are fair decisions, indicating that SAI accusations are, to a large extent, not well investigated (Res Publica, 2017).

Instability and financial crises in the economy, tax evasion (Carfora, 2018) and corruption (Petrescu, 2019; Klarskov Jeppesen, 2018; Jancsics, 2019; Reichborn-Kjennerud et al., 2019 and Nedyalkova, 2017) have a negative impact on the financial discipline (Trîncu-D, 2018) , and the need to prevent and combat them is very important (Pană, 2019). External public audit activity is imperative in ensuring public sector accountability (Cordery & Hay, 2018). To conduct a quality audit, it is essential that the auditors maintain their professional skepticism and perform the appropriate professional judgment (Chersan, 2019). Ensuring high standards of ethics contributes to raising stakeholders’ confidence in the activity of these institutions (Pleşa, 2018). Mass-media (Johnsen et al. 2019), internet (Ortiz-R, 2019), press offices and websites are fundamental aspects of SAI communication strategy in the EU (González et al. 2008). Communication strategy includes three basic concepts; the target audience, the message and the communication channels (González 2013). If the involvement of the media in discussing audit results (Raudla et al. 2016) generates parliamentary attention, it can lead to significant pressures to effectively influence the implementation of recommendations (Van Acker & Bouckaert, 2019). The research conducted by Fertat & Cherkaoui (2018) provides performance measurement using a combined method that includes an analytical hierarchy method (AHP) and a comprehensive Fuzzyva evaluation method. This combined method encourages decision makers to support OHS as a priority in the performance system and to increase the importance of human factors in management systems.

Research Methodology

This study is trying to focus on the importance of an OHS strategy and its impact on sustainable performance, and the authors have proposed a maturity assessment model by analyzing its sensitivity in order to validate the consistency of the strategy. Adjacent to the introduction, conclusions and recommendations, the paper consists of a comparative analysis of the risk factors that affect the non-compliance with legal obligations regarding the communication of the National Audit Authorities from Albania and Romania with the Parliament and the reporting to citizens and other stakeholders, as well as some shortcomings of the legislative framework.

To fulfill the purpose of this paper, the main objective will be to compare the financial communication through annual reports of the two authorities in Albania and Romania, focusing on the institutional and legal differences, as well as presenting an analysis to identify the key factors and their impact on the communication and reporting. The last section will present the main findings of this analysis and the respective recommendations for the Authorities in order to improve their communication with citizens, Parliament and stakeholders, as an essential factor in increasing transparency for the public sector activity and for enhancing citizens’ confidence. Other factors that will be considered are: organizational structure, budget, types of audit, legislation and sanctions.

The research tools which will be used to reach conclusions and recommendations are:

- Research reports and publications;

- Quantitative data provided by the official websites of RCA and ALSAI;

- Comparative interpretation of the data presented in the annual reports on the work of the audit authorities in Albania and Romania for the period 2012-2018;

- Legal framework.

Institutional and Financial Organization

Albania

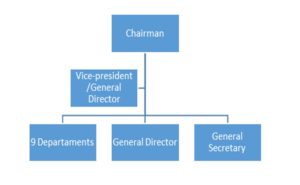

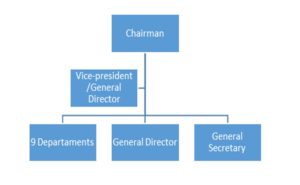

The organization, functioning, attributions and competencies of the ALSAI are defined in the Constitutional Law no. 154/2014, where the audit is defined as the audit activity performed by ALSAI, which includes compliance audit, financial audit, performance audit, IT audit and combined audit, as well as evaluations of the financial management and control system and internal audit units. ALSAI follows effective, efficient and economical use of public funds and state public property, the development of an adequate financial management system, the proper conduct of administrative activities and communication to inform public authorities and the public by publishing audit reports. The specific activities of ALSAI are carried out by departments at the central level (Figure 1); 5 departments are coordinated by the General Secretary and 4 departments by the General Director, except for the Internal Audit Directorate which is directly coordinated by the Chairman.

Figure 1: The ALSAI structure

Figure 1: The ALSAI structure

Source: Authors’ projection after Decision No. 238 of 21.12.2018 (amended)

The Chairman of ALSAI is elected by the Assembly at the proposal of the President of Albania for a seven-year term, with the possibility of re-election. The ALSAI is funded from the state budget in each draft budget of the Committee on Economics and Finance, which is examined and presented for approval to the Assembly as an integral part of the budget.

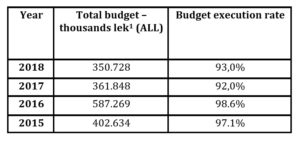

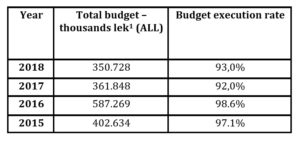

Table 1: ALSAI Budget for the period 2015-2018

Source: Authors’ projection based on www.financa.gov.al

As can be seen from Table 1, the ALSAI budget increased significantly in 2016 as compared to 2015, accompanied by a decrease in 2017 and 2018. The budget execution rate is steadily rising in 2016 and 2018, but there is a decrease in the rate in 2017 compared to 2016.

By 2018, the total number of employees was 191 employees. The average age until the end of 2018 was 42.6 years compared to 48 years in 2012, which translates into the rejuvenation of the staff.

Romania

The organization and functioning of the RCA are defined by Law no. 94/1992,

republished, amended and completed, as well as in its Regulation. The Court of Accounts’ activities are control, financial audit, performance audit, compliance audit and other activities based on the competences provided by law (Pintea & Achim, 2009; ECA, 2019).

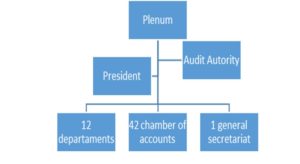

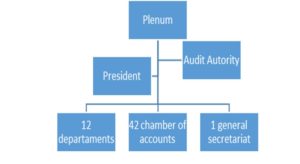

Leadership is exercised by the plenum of the Court of Accounts, which is comprised of 18 members appointed by Parliament, acting as accounts advisers. Schematically, the structure of the Court of Accounts is set out in Figure no. 2.

Figure 2: Structure of Romanian Court of Accounts

Source: Authors’ projection after Law no. 94/1992, republished, as subsequently amended and supplemented.

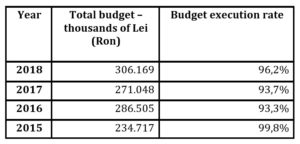

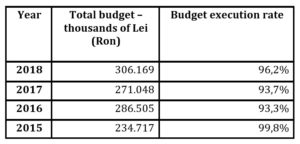

The departments are coordinated by two vice-presidents, except for two departments that are directly coordinated by the President, who is also coordinating the work of 4 Directorates. The RCA is financed from the state budget, and the draft budget is approved by the plenum, after which it is submitted to the Government to be introduced into the state budget and be subjected to the approval of the Parliament. As can be seen from Table no. 2, there is an increasing trend year after year in the RCA budget with a slight decrease in 2017 compared to 2016.

Table 2: Court of Accounts Budget for the period 2015-2018

Source: Authors’ projection based on the RCA Activity Reports 2015-2018

At the RCA level, at the end of 2018, there is a total number of 1,598 employees. The largest share regarding the age profile of the auditors is held by staff aging between 41 and 45 years (21.9%) compared to 2012 where it was between 56 and 60 years (20.3%).

Financial communication based on the annual activity reports of ALSAI and RCA

Under the Constitution and the relevant laws, the National Audit Authorities of Albania and Romania are required to submit their annual report of their activity to Parliament. Financial communication through annual reports on external public audit activity is based on the principles of transparency and efficiency in the use of public resources to improve the public sector and strengthen relations with stakeholders.

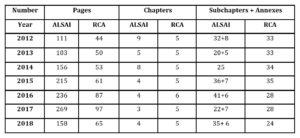

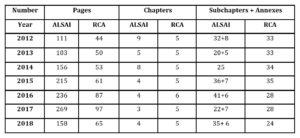

Table 3: Synthesis of SAIs annual reports’ size for the period 2012-20118

Source: Authors’ projection

Table 3 shows that the number of reports pages, in both authorities, increases steadily throughout the period 2012-2017, and in 2018 the volume of reports decreases. The most massive ALSAI report is from 2017 (269 pages) and the largest report of RCA is also from 2017 (97 pages). This evolution of the report’s contents as compared to 2012 is determined by the increase in the quality level. The annual RCA reports are less voluminous than the ALSAI’s annual activity reports. This is explained by the fact that RCA, aside from the Annual Activity Report, is publishing the following:

- Annual reports on local public finances,

- Annual public report,

- Report on criminal complaints,

- Special Reports on the activity of public internal audit structures etc.

An important place in the ALSAI report is held by the framework for measuring this institution’s performance, which is elaborated based on the measured dimensions with 25 indicators in 6 domains and the annual accounts of ALSAI (20 pages for 2018). The implementation of RCA budget is generally explained in the annual activity report, in 2 pages. The RCA report presents the activities of the Ethics Committee, while in the ALSAI, this committee does not exist.

Types of Audit

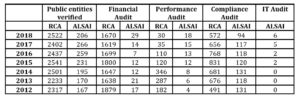

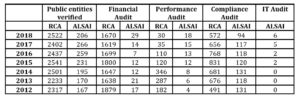

ALSAI fulfills its mission and carries out its activity through financial audit, compliance audits, performance audits, information technology audits missions, as well as evaluations of internal control and internal audit units. The RCA’s competencies include control, financial audit and performance audit (Trincu-D, 2018). Table no. 4 gives an overview of the evolution of audit missions and the number of public entities audited between 2012 and 2018:

Table 4: Evolution of audit missions and the number of public entities audited

Source: Authors’ projection

As noticed, the number of audited public entities, as well as the number of audit missions, varies from year to another. It follows that the RCA’s financial audit missions are predominant compared to other types of audits, while ALSAI has conducted the highest number of compliance audits. A drastic reduction was seen in performance audits and financial audits performed by the RCA, while their number grew in the case of ALSAI. The number of compliance audits has decreased for both authorities. An interesting fact is that ALSAI performs IT Audit, while the RCA does not, as this type of audit is not mentioned in the legal acts. Both authorities independently decide on their action plan. Referring to their official website, it is noted that ALSAI has published audit plans since 2012, while the RCA published them for the first time in 2018. The annual reports of ALSAI do not explain the factors that led to deviations from the plan of audit missions scheduled at the beginning of the year, indicating that better planning of the audit resources is needed (Xhani et al. 2020). Klarskov Jeppesen et al. (2017) identified four strategic options for the development of SAI; strategies based on performance audit, financial audit, portfolio strategies (Pollitt, 2003) or hybrid strategy. From the analysis of the activity carried out by the two institutions, it is observed that ALSAI and RCA are oriented towards a portfolio strategy that includes financial, compliance and performance audits.

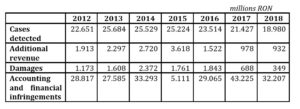

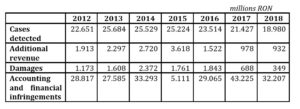

Damages and Criminal Investigation Bodies

Audit mission recommendations help the public sector to function properly and improve performance continuously. However, auditors have found cases of non-compliance with legal provisions, deviations, irregularities, errors, damages, inefficient spending or adverse effects on the state budget. The financial impact for the period 2012-2018, according to the data presented in the RCA activity report, is shown in Table no. 5:

Table 5: Financial Impact

Source: Authors’ projection

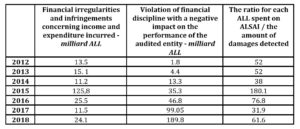

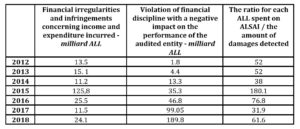

Financial irregularities and infringements found by ALSAI are presented in Table. 6. The ratio between the amount of funds detected and required to be netted against the actual budget expenditures of the ALSAI, is one of the most important indicators of the institution’s performance.

For the period 2012-2018, it is shown that, for every Lek (ALL) spent on ALSAI, it required 100.5 ALL to indemnify. RCA does not apply this indicator, which shows the usefulness of its work. The relationship between the financial saving resulting from the auditors’ activities and the cost of these activities, is not mentioned in the RCA Annual Report (Oţetea et al. 2015).

Table 6: Economic damages

Source: Authors’ projection

Within the competencies established for both authorities for all identified and found damages, the criminal prosecution bodies were notified. Total referrals for criminal investigation by RCA in the period 2010-2017 are 752 (amounting at 11.2 milliard RON in total), of which 171 are resolved and 581 unresolved damages worth 10,7 milliard RON are unresolved. While the ALSAI annual reports contain a formal general description (one page accompanied by an annex for the current year) without explaining which concrete cases had been resolved or for which the investigation had been closed, as it is published when discovered (including the subject to which the denunciation refers, the employee’s job, etc.). The same thing can be observed in the RCA Annual Activity Report.

Infringements and sanctions

Chapter 7 of the RCA Law contains relevant information on infringements and sanctions found by auditors employed by RCA, and amounts representing fines which are revenue to the state budget. Article 26 of ALSAI Law no. 154/2014 describes access to official documents of audited entities and in the case where the audited entity fails to comply, the ALSAI has the right to present these cases to the highest administrative body or juridical authorities (in the latter case, the procedure takes a long time and requires financial and human involvement), without the possibility to propose sanctions.

In the analyzed reports of the RCA, there is no mention of cases of sanctions, and in the ALSAI reports, several cases are highlighted, but the way they were solved is not presented.

Conclusions

Any public sector entity that is allocated as state budget funds is audited by the National Audit Authority concerning the way these funds are used, providing Parliament with reports on the use and management of allocated funds. The results of this study can serve as a guide for leadership in the process of improving the quality of the institution’s activity in order to increase transparency vis-à-vis citizens and stakeholders.

Numerous studies have highlighted the importance of SAI and how it has contributed to the good management of public funds. Therefore, RCA and ALSAI are the highest institutions of the rule of law. The following conclusions can be drawn from the analysis carried out in this article:

- ALSAI is led by the Chairman, while the management of RCA is by the Plenum and executive management is by the President.

- The Romanian Audit Authority is part of the RCA structure, and in Albania it is supervised by the Prime Minister.

- The staff structure is favorable, because there is a convergence of experience, qualities and technical competencies of auditors that are old in a profession with the newly recruited staff, which brings along the sustainable development and support for the organization in the future.

- ALSAI, utilizing indicators for performance measurement, analyzes its activity and identifies aspects that need to be improved, while the RCA does not apply this methodology to measure performance in order to guide leadership.

- In the Constitution of Romania, as well as in that of Albania, the term “control” is used, which has the same meaning as “audit”.

- The legal framework on infringements and sanctions in Romania is more complete.

- The implementation rate of the RCA and ALSAI budgets was not 100% achieved in any of the analyzed periods.

- The RCA does not perform the IT audit, while in Albania, the number of cases of IT audit increases year after year.

- After making a research on the ALSAI website, it is noted that the political party’s activity has never been audited, leading to ALSAI’s failure to comply with the law.

- ALSAI publishes each final complete audit report on the official website since 2012, while the complete reports for each audited institution are not published on the RCA

- ALSAI has developed the Communication Strategy for the period 2017-2019 and RCA for the period 2016-2020.

To fulfill the conditions resulting from the Cooperation Agreement between the RCA and ALSAI, this paper proposes that the issues addressed in this study should be communicated to the two authorities to be implemented in practice as soon as possible. Future studies are necessary to follow up the practical application of the present agreement and also to conduct a study on the impact of audit recommendations on the efficiency of the use of budgetary resources. The expectations that citizens have for the future of the public sector, are many, so ALSAI and RCA must better demonstrate the usefulness of their activity by:

- Improving communication channels effectively through the OHS communication strategy to provide complete and clear information.

- Identification of the weaknesses and strengths of the communication and reporting mode.

- Familiarization with the new audit approaches.

- Stimulating the professional training of the employees.

- Changing the perception of the audited institutions based on the necessity and usefulness of the activity carried out by the RCA and ALSAI auditors.

- Initiating legislative changes for compliance with International Standards and best practices of external public audit.

- Echoes that appear in mass-media about the employees referred for prosecution and whose offenses are not confirmed by the criminal investigations conducted adversely, affect the public. The National Audit Authority in the two countries, in addition to making the general public more familiar with cases where the auditor’s judgment is wrong, need to recruit highly qualified staff in the field to ensure continuous professional training of auditors in order to correctly identify cases that constitute an offense.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

References

- Avram, A., Avram, CD. and Avram, V. (2014), ‘Research and development expenditures between discretionary costs and source for economic growth,’ Romanian Journal of Economics, 39(2), 49-66.

- Bonollo, E, (2019), ”Measuring supreme audit institutions outcomes: current literature and future insights,” Public Money & Management, [Online], [Retrieved August 10, 2019], https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2019.1583887

- Bringselius, L. (2018) ‘Efficiency, economy and effectiveness—but what about ethics? Supreme audit institutions at a critical juncture,’ Public Money & Management, 38(2), 105-110.

- Carfora, A., Pansini RV. and Pisani, S. (2018), ‘Regional tax evasion and audit enforcement,’ Regional Studies, 52(3), 362-373.

- Chersan, I. C. (2019) ‘Audit quality and several of its determinants,’ Audit Financiar, XVII (1(153)), 93-105.

- Clark, C., Martinis, de M. and Kapardis, M. K. (2007). ‘Audit quality attributes of European Union supreme audit institutions,’ European Business Review, 19(1), 40-71.

- Cordery, CJ and Hay, D. (2018), ‘Supreme audit institutions and public value: Demonstrating relevance,’ Financial Accountability & Management, 35(2), 128-142.

- Cornelia, D. (2012) ‘Great Britain and Germany supreme audit institutions,’ Annals of the University of Oradea: Economic Sciences, 1(1), 695-701.

- Court of Accounts (2012-2018) “Annual reports concerning the activity of the Court of Accounts”, [Online], [Retrieved July 09, 2019], http://www.curteadeconturi.ro/Publicatiit.aspx

- European Commission (2019) “Albania 2019 Report”, [Online], [Retrieved June 29, 2019], https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/sites/near/files/20190529-albania-report.pdf

- European Court of Auditors (2019), Public audit in the European Union [Online], [Retrieved August 18, 2019], https://www.eca.europa.eu/Lists/ECADocuments/Book_Public_Audit_in_the_EU/Book-Public_Audit_in_the_EU_EN.pdf

- Fertat, L. and Cherkaoui, A. (2018), ”Occupational Health Maturity by Combined AHP and Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation Methods,’ Communications of the IBIMA, [Online], [Retrieved August 10, 2019], https://ibimapublishing.org/articles/CIBIMA/2018/812944/

- González, B., García-Fernández, R. and López-Díaz, A. (2013) ‘Communication as a Transparency and Accountability Strategy in Supreme Audit Institutions’, Administration & Society, 45(5), 583–609.

- González, B., López, A. and García, R. (2008), ‘Supreme Audit Institutions and their communication strategies,’ International Review of Administrative Sciences, 74(3), 435–461.

- Jancsics, D. (2019) ‘Corruption as Resource Transfer: An Interdisciplinary Synthesis. Public Admin Review, 79(4), 523-537.

- Jansons, E. and Rivza, B. (2017), ‘Legal aspects of the Supreme Audit Institutions in the Baltic Sea region’ Proceedings of the 23rd Annual International Scientific Conference “Research for Rural Development”, ISSN 2255-923X, 17 – 19 May 2017, Jelgava, Latvia, 112−117.

- Jantz, B., Reichborn-Kjennerud, K., Vrangbaek, K. (2015) ‘Control and Autonomy—The SAIs in Norway, Denmark, and Germany as Watchdogs in an NPM-Era?’ International Journal of Public Administration, 38(13-14), 960-970.

- Johnsen, Å. (2019). ‘Public sector audit in contemporary society: A short review and introduction,’ Financial Accountability & Management, 35(2), 121– 127.

- Johnsen, Å., Reichborn‐Kjennerud, K., Carrington, Th., Klarskov Jeppesen, K., Külli, T. and Vakkuri, J. (2019) ‘Supreme Audit Institutions in a High‐impact Context: A Comparative Analysis of Performance Audit in Four Nordic Countries,’ Financial Accountability & Management, 35(2), 158-181.

- Klarskov Jeppesen, K, (2018), ”The role of auditing in the fight against corruption,” British Accounting Review. [Online], [Retrieved July 20, 2019], https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2018.06.001

- Klarskov Jeppesen, K., Carrington, Th., Catasús, B., Johnsen, Å., Reichborn‐Kjennerud, K. and Vakkuri, J. (2017) ‘The Strategic Options of Supreme Audit Institutions: The Case of Four Nordic Countries,’ Financial Accountability & Management, 33(2), 146 – 170.

- Law No. 90/2016 “On the organization and functioning of the Audit Agency for the EU-Accredited Assistance Programmes in the Republic of Albania”. [Retrieved July 07, 2019], http://www.aapaa.gov.al/

- Law No. 94/1992 “On the organization and functioning of the Court of Accounts”, republished, [Retrieved July 01, 2019], http://www.curteadeconturi.ro/Legi/Law%20no.%2094-1992%20reissued%202009.pdf

- Law No. 154/2014 “Organization and functioning of State Supreme Audit Institution”, [Retrieved July 01, 2019], http://www.klsh.org.al/web/alsai_s_new_law_english_1715.pdf

- Nedyalkova, P. (2017) ‘Study on the Factors Affecting the Assessment of Internal Audit in the Public Sector’, International Journal of Business and Social Science, 8(7), p. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3367482

- OECD (2017) “Developing effective working relationships between supreme audit institutions and parliaments”, SIGMA Paper no.54. [Online], [Retrieved August 18, 2019], http://www.sigmaweb.org/publications/Supreme_audit-institutions-and-parliaments-SIGMA-Paper-No.%2054.pdf

- Ortiz Rodríguez, D., Alcaide-Muñoz, L., Flórez-Parra, J. M., López-Hernández, A. M. (2019) Organizational Auditing and Assurance in the Digital Age: Transparency in Latin American and Caribbean Supreme Auditing Institutions. IGI Global, Hershey, Pennsylvania, USA.

- Oțetea, A., Tita, CM. and Ungureanu, AM. (2015), ‘The performance impact of the Supreme Audit Institutions on national budgets. Great Britain and Romania case – comparative study,’ Proceedings of the 22nd International Economic Conference (IECS), Procedia Economics and Finance, ISSN: 2212-5671, 15-16 May 2015, Sibiu, Romania, 27, 621– 628.

- Pană, I. (2019) ‘Controlul şi prevenirea infracţiunilor,’ Buletinul Universităţii Naţionale de Apărare „Carol I”, 6(1), 112-121.

- Peci, A., and Rudloff Pulgar O. C. (2019), ‘Autonomous bureaucrats in independent bureaucracies? Loyalty perceptions within supreme audit institutions,’ Public Management Review, 21(1), 47-68.

- Petrescu, C. C. (2019), ”The magnitude of corruption in Romanian public universities: Preliminary results of a research based on national particularities,” Journal of e-Learning and Higher Education, [Online], [Retrieved August 02, 2019],, https://ibimapublishing.org/articles/JELHE/2019/638013/

- Pierre, J. and de Fine Licht, J. (2019), ‘How do supreme audit institutions manage their autonomy and impact? A comparative analysis,’ Journal of European Public Policy, 26(2), 226-245.

- Pintea, MO and Achim, SA. (2009), ‘Supreme audit institutions. Comparative study for the central and Eastern European countries members of the European Union,’ The USV Annals of Economics and Public Administration, 9(1(9)), 235-242.

- Pleşa, IT. (2018), ‘The Supreme Audit Institutions’ Ethics Challenges in the Contemporary Society,’ Proceedings of the 9th LUMEN International Scientific Conference Communicative Action & Transdisciplinarity in the Ethical Society (CATES), ISBN: 978-1-910129-16-6, 24-25 November 2017, Targoviste, Romania, 211-223.

- Pollitt, C. (2003) ‘Performance audit in Western Europe: trends and choices,’ Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 14 (1–2), 157-170.

- Pollitt, C and Summa, H. (1997), ‘Reflexive watchdogs? How supreme audit institutions account for themselves,’ Public Administration, 75(2), 313-336.

- Pollitt, C., Girre, X., Lonsdale, J., Mul, R., Summa, H. and Waerness, M. (1999). Performance or Compliance?: Performance audit and public management in five countries, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Qendra “Res Publica” (2017) “Efektiviteti i kallëzimeve penale nga Kontrolli i Lartë i Shtetit” [Online], [Retrieved June 25, 2019], https://www.osfa.al/sites/default/files/respublica_-_efektiviteti_i_kallezimeve_penale_te_klsh.pdf

- Raudla, R., Taro, , Agu, C. and Douglas JW. (2016), ‘The impact of performance audit on public sector organizations: The case of Estonia, Public Organization Review, 16(2), 217-233.

- Reichborn-Kjennerud, K., González-Díaz, B., Bracci, E., Carrington, Th., Hathaway, J., Kim Klarskov Jeppesen, K. and Steccolini, I. (2019). Sais Work Against Corruption In Scandinavian, South-European And African Countries: An Institutional Analysis, The British Accounting Review, [Online], [Retrieved August 11, 2019], https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2019.100842.

- Supreme Audit Institution of Albania (2012-2018) [Online], [Retrieved July 09, 2019], http://www.klsh.org.al/web/Raporti_i_Aktivitetit_81_1.php

- Trîncu-Drăguşin, C. P. (2018) ‘Landmarks regarding the external public audit in Romania,’ Annals of the UCB – Economy Series, 1(1), 193-200.

- Xhani, N., Avram, M., & Iliescu Ristea, M.-A. (2020). ‘The Development of Auditing in the Public Sector in Albania and Responsible Institutions’. Journal of International Cooperation and Development, 3(1), 38. https://doi.org/10.36941/jicd-2020-0004

- Zuccolotto, R and Teixeira, ACM (2014), ‘Budgetary transparency and democracy: the effectiveness of control institutions, ‘ International Business Research, 7(6), 83–96.

[1] The lek (code: ALL) is the official currency of Albania.