Introduction

From military structures to pioneers to gurus of schools of strategic thinking, the practice and corresponding theory of strategy have evolved and become increasingly complex over time. However, the literature on strategic management is of more recent date.

Interestingly, while the history of scientific management started with the seminal works of Taylor (1911), Gantt (1916) and Fayol (1917), in 1911, Harvard Business School introduced a course designed to improve the strategic skills of general managers, named “Business Policy”, which later, in 1969, became a mandatory course for all American business schools (Kazmi and Kazmi, 1992).

Peter Drucker is considered the founder of modern management, authoring influential books on management (Drucker, 1954; 1964; 1971; 1985) in the larger technology and socio-economic context. The schools of management thought have evolved along the twentieth century and have culminated in the second part of the last century with successful theories on strategic management, associated with concepts as strategy, strategic thinking, strategic planning and strategic plan as well as dominant figures of scholars like Alfred Chandler-Jr., Harry Igor Ansoff, Michael Porter, and Henry Mintzberg. Nevertheless, Mintzberg is significantly important not only for inventorying not less than ten different “schools” of strategic management thinking, but also for signalling “the rise and fall of strategic management” (Mintzberg, 1994) in that rigid form.The turbulent politico-economic environment at the border of two millennia (Drucker, 1980; 1995), characterized by the dissolution of many centrally planned economies and global crises, has demonstrated that rigidity associated with strategic planning could not provide viable management solutions anymore. Newer types of more flexible schools of thought – still strategic – started to gain ground among top managers and strategists such as: Foresight (Loveridge, 2003) in all sectors, Marketing as a strategy (Kumar, 2004), and Blue ocean strategy primarily in business (Kim and Mauborgne, 2004).

The focus of this paper is on the manner in which the blue ocean strategy is working in some practical situations, following observed cases, in which the transition has proved to be more difficult in practice than expected in theory. In view of that, the authors’ foremost objective is to provoke a discussion on “the colour of the ocean” (the metaphor for the current competitive market): how it turns from “red” of fierce competition to “blue” of the irrelevant competition – through the “purple ocean”. Therefore, the paper is structured as follows: research methodology; literature survey on strategy and strategic management concepts; Blue Ocean strategy as a path starting in the red ocean; the case of the Purple Ocean; followed by conclusions and managerial implications, as well as limitations and further research potential.

Research Methodology

Being mostly descriptive, the paper is based on a qualitative interpretation of data resulting from both secondary research (literature survey) and primary research (authors’ own experience as managers and consultants, cumulating four decades).

The primary research was completed by interviews with managers from companies that experienced the implementation of the blue ocean strategy – in order to better understand the context of the transition from one type of strategy to another. The thesis of “purple ocean” is supported by cases and examples (case method).

The qualitative literature review was doubled by the triangulation method. This consists in inquiring multiple sources and searching for the convergence of information in order to validate the data.

Literature Survey

In 1962, Alfred Chandler-Jr. published the history of the large American businesses (as industrial enterprises) emphasizing their strategy and structure. He defined strategy as being the way of achieving the organization’s long-term objectives, using a certain plan of action and resources needed: “Strategy can be defined as the determination of the basic long-term goals and objectives of an enterprise; and the adoption of courses of action and the allocation of resources necessary for carrying these goals” (Chandler, 1962, p.13). Jeffs (2008) defines strategic management as being a process of formulating the strategy, evaluating and implementing it, with the purpose of accomplishing the organization’s objectives. A similar definition is given by Lynch (2018), who claims that strategic management consists, in essence, in the identification of the organization’s scope, which can be achieved through a certain plan of actions.

Harry Igor Ansoff, an applied mathematician and business manager, is considered the father of strategic management whose works on strategic management cover about three decades, and are continued and highlighted by his followers (Hussey, 1998, 1999; Martinet, 2010; Moussetis, 2011; Ansoff and Antoniou, 2006; Ansoff and McDonnel, 2008; Ansoff et al., 2019). Ansoff was the founder of the design school in strategic management. According to Ansoff (1965; 1979; 1987; 1988), strategic planning is represented by a general plan which is cascaded in the organization to more specific medium- and short-term plans. From the school’s perspective, strategic planning is a mathematics model which consists of quantifiable processes and prediction of future events based on a variety of patterns.

Another remarkable author is Michael Porter with his theory on competitive strategy and the five forces model (Porter, 1986). Yet, before him, there were other significant scholars with remarkable works on strategic management (Steiner, 1979; Tregoe and Zimmerman, 1980; Pearce and Robinson, 1982; Thompson and Strickland, 1983; Hill & Jones, 1989) – most of them championing for the right “strategy formulation and implementation”. Moreover, it is important to mention “Kaisha”, the Japanese corporation and its management (Abegglen and Stalk, 1985) that followed the principles of competitive advantage in their strategy to reach the status of global players.

Mintzberg (1987) claims that strategy discipline has different definitions and approaches, and all of them are valid and may depend on each other. Mintzberg suggests the 5Ps-concept in which the strategy can be: a plan, which refers to the process of strategy as an intentional action; a ploy, which refers to a short team strategy; a pattern, which represents the process of strategy as a result of consistent activities; a position, referring to a strategy built for the organization, which is in a certain position in the market; and strategy as a perspective, in order to define a certain way of working. In line with this understanding, Mintzberg, Ahlstrand and Lampel (1998) managed to integrate the complexity and variety of perspectives over the concept of strategy into ten schools of thought, in order to obtain a holistic approach for it. On the other hand, Ansoff (1991), reconsidering the premises of strategic management of the design school, has criticized the way Mintzberg made his categorization of the schools of strategic thought. Shekhar (2009) also criticized Mintzberg’s grouping criteria.

From the standpoint of the objective of this paper, it is remarkable to notice that Mintzberg (1994, 2013) trumpeted, more than two decades ago, not only the rise to prominence but also the “fall of strategic management” – at least in forms known at the time of his work. In addition, based on his extensive experience of business consulting, Mintzberg was able to note that, in spite of excellent managers and strategic management results, seeing a real strategic plan in operation was a problem.

More recently, Bonsu (2019) argues that strategic management represents the decisions made by leaders in order to obtain a competitive advantage against rivals, and maximize profit. According to Hitt, Ireland and Hoskisson (2017), the role of strategic management is to gain a competitive advantage for the organization through a set of commitments that are integrated in a coordinated relationship with actions.

In a more complex way, Lynch (2018) defines strategic management as being the emergent initiatives taken by the general manager of an organization, on behalf of the owner, in order to enhance the organization’s performance in the external environment by properly using the available resources.

To conclude, strategy scholars are approaching strategic management from two different angles: prescriptive and emergent perspectives. The prescriptive approach refers to the process of strategy as being rational, planned in advance and then implemented by the organizations (“strategy formulation & implementation”). The scholars who support the emergent approach argue that strategy process is just a pattern, a result of cultural understanding and learning process of an organization and cannot be planned due to the continuous internal and external environmental changes (Partridge and Sinclair-Hunt, 2005; Bindra Gupta, Parameswar and Dhir, 2019).

Nickols (2016a) highlights the three forms of strategy (general, corporate, and competitive). He also describes the main concepts involved in discussions about strategy issues (Nickols, 2016b). There is logic in the basic activities related to the concept of strategy: strategic thinking that precedes and includes strategic management, which, at its turn, means strategy formulation, strategic planning and strategy deployment.

Kaplan and Norton (2001) referred to the company indicators, and Doer (2018) theorized the goal-setting system (also known as OKRs – Objectives and Key Results). The system described was applied in the 60s by Andy Grove at Intel based on a simplified, more flexible and practical version of strategy theories, which were previously described by Drucker (1954) and Ansoff (1965).

Beside the earlier warnings that have signaled the decline of strategic management which was understood as rigid strategic planning, there are two new lines of thought in strategic thinking that are worth mentioning; both being marketing-inspired and, coincidentally or not, both issued in the same year: Marketing as a strategy (Kumar, 2004) and Blue Ocean strategy (Kim and Mauborgne, 2004) Both have received appreciation from the business community, as new methodological approaches, supplying tools for strategic decisions.

Inspired by predecessors – from Kotler (1967) to Hamel and Prahalad (1994),, Kumar (2004) supports the idea of driving growth and innovation using the Three Vs (Valued customer; Value proposition; Value network). Valued customer, which is a basic principle in marketing, answers the question “whom to serve?”; Value proposition (which also is a core-concept that plays a central role in the business model canvas (Osterwalder, 2004; Osterwalder and Pigneur, 2002; 2010) answers the question “what to offer?”; and Value network addresses the delivering issue – “how to deliver?”. The novelty of the idea lies in integrating them all and, simultaneously, raising the marketing up to the strategic level: turning from “market-driven” to “market-driving”, which is more meaningful than a simple wordplay.

Levinthal and March (1993), Ansoff and Antoniou (2006) criticize traditional schools of strategic thinking for failing to consider long-term strategy prospects.

– there are three tendencies against rigid traditional strategic planning:

Shortening the time horizon of the strategic planning as well as business planning;

Flexibilization of the plans, still keeping the exercise of planning (as the former USA President Eisenhower said once: “plans are worthless, but planning is essential”);

Paradoxically, using the longer-term simulation exercises of exploring the future – foresight-type (Loveridge, 2003; Popper, 2008) in order to make better prepared strategic decisions.

The last approach is natural, because longer-term predictions are possible, thanks to the more advanced technology of big data mining.

The last two ways could be combined because foresight assumes flexibility so that flexible foresight scenarios allow designing strategies for surmounting unexpected obstacles like “black swans” (Taleb, 2007): highly improbable events or risk factors with extremely low probability to occur and high impact. Extending his theory, Taleb (2012) develops the concept of “antifragility”. Conversely, the Blue Ocean strategy seems to be displaying features of the first two tendencies.

The path from the Red to the Blue Ocean

Kim and Mauborgne (2004) have developed the theory of Blue Ocean strategy, which received remarkable success: 3.5 million copies of the book were sold in five continents, and translated in 43 languages. This theory followed the line of raising marketing at the strategy level: focusing on the product’s characteristics that customers appreciate the most.

In spite of the models and tools developed to analyse the current situation and to find the best strategic move from the current red ocean of fierce competition (dominated by predator sharks) to the much-desired, serene blue ocean where competition becomes irrelevant (because new markets are created), the transition is not instantaneous. It takes time that might be significant, and the transition path might be complex, letting aside that competition is not stagnant. Therefore, Harvard scholars have further developed new guidelines and tools to be used in the process of this transition (Kim and Mauborgne, 2017). The authors have already seized the obstacles against this transition process; therefore, it should be carefully designed as a non-disruptive formation, by combining elements of psychology with practical tools to be used in the real business environment.

The travel guide from the red ocean to the blue one could be used not only by small-to-large companies but also by individuals, teams, and even non-profit and public administration organizations, building self-confidence and “seizing new growth”, by owning and mastering the change.

It is significant to mention that, in management, many new concepts have roots in traditional theories. A good example is the goal-setting system (Doer, 2018) that continues the line of thinking initiated by Drucker (1954) and Ansoff (1965), and revived by Kaplan and Norton (2001). The strategy of the blue ocean is a similar case.

Creating a “Blue Ocean” is not always easy. However, in those limited cases when or if an organization manages to do it, the competition becomes relevant again in a short period of time due to its quick reaction. A more sustainable way of maintaining a competitive advantage is by organizational flexibility, by being open to new opportunities, i.e. by entrepreneurial behaviour (Şişu and Scarlat, 2020) so that direct competition will become less relevant.

As today’s pace of technological progress is so fast that, while the “blue ocean change” is implemented and the company is on its way from the red to the blue ocean, the environment changes itself with newer and newer technologies, newer customer needs, so an organization is required to continuously innovate in order to be sustainable. It is not about choosing the right strategy, but the most profitable mix of strategies.

In addition, this change – like any other transition process – is not a safe way; it has its own risks. On the other hand, it takes time; it has a certain duration that might be significant (letting aside the practical situation when the transition never ends or ends back in the red ocean of fierce competition, failing to implement its Blue Ocean strategy). Self-confidence and the tools to help could shorten that duration and make the transition smoother, yet it is a period in which the ocean is not that red anymore, but it is not blue yet either.

A case of failing to reach the “Blue Ocean”

A medium-sized company, which was active in the services industry in Romania, probably during its maturity stage, have reached the “plateau of sales” during the period of the relative economic stability that followed the 2008-2010 global financial crisis.

The company was led by a dynamic manager, a fresh graduate of an MBA program, who eventually became familiar with the strategy of “Blue Ocean”. He decided to apply the appealing strategy of the “blue ocean” in his company, and associated tools and trained his staff accordingly. Subsequently, the marketing & sales team has received the task to market and sell the company products, using the “blue ocean” tools.

The company’s products were rather innovative products sold in association with yearly subscriptions for the services provided. There were individual customers, but the purchasing decisions were not necessarily made by the end-users but by the representatives of their associations – a situation defined as “B2X” rather than B2C or B2B (Scarlat and Şişu, 2016; Şişu and Scarlat, 2019).

After almost two years, the sales of the company did not increase significantly, and the company was not in a red ocean anymore, neither in the much-desired blue ocean; it was about the same market, with fewer competitors, yet the top ones were still there.

A deeper and finer analysis would unveil the root causes, describe the evolutionary path, and provide fair explanations for the results mentioned above, which might go behind the goal of this paper.

This story is not to criticize nor minimize the theory of Blue Ocean strategy, it is just a practical, concrete example of how things could turn out in the real business environment – probably more frequently than the “business-happy-end” success stories. In addition, the case illustrates a situation that should be identified as “purple ocean”, to describe, metaphorically, an intermediate position between red and blue colours.

It is worth noting that in other circumstances, the reverse situation was observed: even in the case of reaching the “blue ocean”, various external factors (e.g. new competition or crises) or internal reasons (as strategic management errors) cause some companies to fall back from the blue ocean to an intermediary status (neither blue anymore nor red yet); calling it purple ocean as well.

The concept of the “purple ocean” could be understood in several ways: (i) situation of transition from the blue ocean to the red ocean; (ii) a real situation between ideal, theoretical “red” and “blue” models; (iii) a combination (mix) of strategies or characteristics of both strategic situations (“red” and “blue”).

Admitting that “blue and red oceans have always coexisted”, Kim and Mauborgne (2004, p.190) have declared the following: “Creating blue oceans is not a static achievement but a dynamic process. Once a company creates a blue ocean and its powerful performance consequences are known, sooner or later, imitators appear on the horizon. The question is, how soon or late will they come? Put differently, how easy or difficult is the blue ocean strategy to imitate?” (Ibid., p.185).

The Blue Ocean strategy is also about gaining a competitive advantage by continuous innovation. Therefore, the next section is about how to maintain the competitive advantage by innovation (in particular, by implementing an innovation management system).

Four models for gaining competitive advantage

In the context of a constantly changing business environment, innovation and strategic management represent a way to improve or build new products or services that help organizations gain competitive advantage on the market (Melendez, Dávila and Melgar, 2019).

Maier et al. (2019) link innovation with sustainability and argue that one of the main conditions for an organization to maintain competitive advantage on the market is to implement a system of innovation management.

In the last two decades, many organizations adopted disruptive innovation as part of their culture and strategy. Disruptive innovation turned from being a hot topic in the late 90s and early 2000s to become a mainstream topic today. Most of the organizations struggle to develop an innovative product that helps them swim in the blue ocean, although it is for a short period of time, and only a few of them succeed.

Examples of disruptive innovators are as follows: Apple with iPhone product followed shortly by Samsung; Uber with mobility services followed by Lyft or TaxiFy/Bolt; Booking with accommodation services, followed by Airbnb; and Bitcoin with virtual currency, followed by Ethereum, etc.

Christensen argues that “success is not built into the definition of disruption: Not every disruptive path leads to a triumph, and not every triumphant newcomer follows a disruptive path” (Christensen, Raynor & McDonald, 2015, p.8).

Bonie and Joseph (2019) stated that the sustainability of organizations is effectively generated by disruptive or transformative innovation. They underline that innovation is a long-term commitment. They also proposed four strategic paths (two direct and two indirect models) that help organizations generate disruptive or transformative innovation.

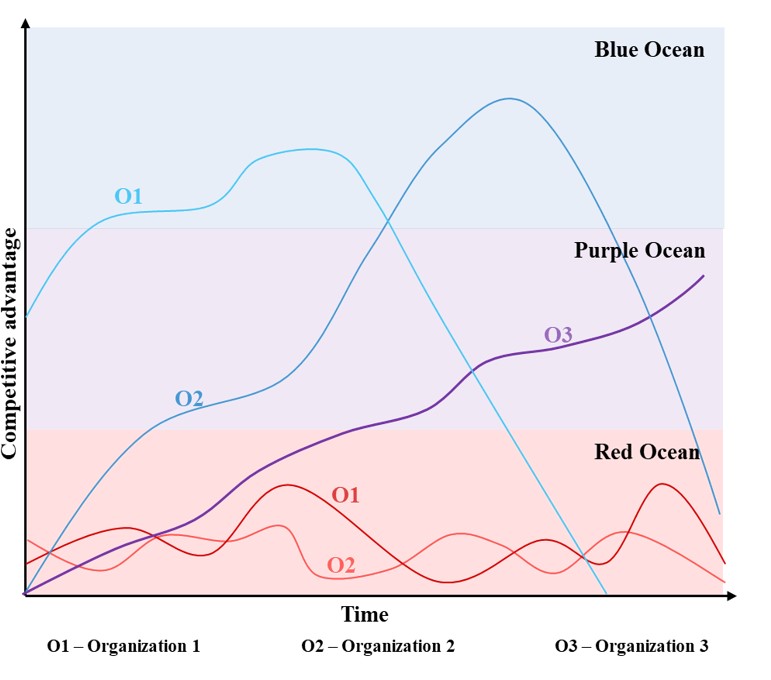

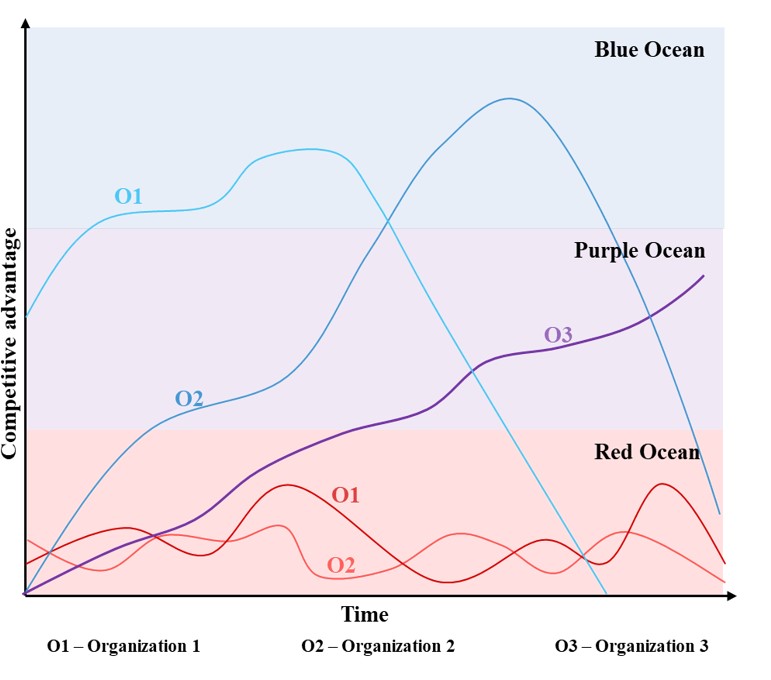

Undoubtedly, the Blue Ocean strategy is generating high profitability for the organization, but for a limited period of time. On the opposite side, the red ocean means increased consumption of resources and high risks caused by constant competition. The “purple ocean” corresponds to the adaptive and sustainable strategy, through innovation. This is the middle way (between the oceans) of an organization which, although it is in the red ocean with its core activity, develops a new product that generates resources to ensure the organization’s survival (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Purple Ocean – graphic representation

The Purple Ocean refers to organizations that have products (goods and/or services) that achieved maturity, and develop new channels to distribute new products, different from their core activity, to ensure long term survival and sustainability. This kind of organizations are “fighting” against their direct competitors on core products in red oceans but are not flexible enough to reallocate resources and focus on new and innovating products and services.

Organizations that are adopting Purple Ocean strategies are those who are seizing opportunities to build new lines of products in the existing markets, different from their core markets, using one or more models – as proposed by Boni and Joseph (2019).

An example of Purple Ocean

Daimler, the German car producer, entered the car-sharing market in 2009, with the car2go urban mobility application, which represented a new business pillar, different than Daimler’s core business. (https://media.daimler.com )

In this particular case, Daimler is not creating a blue ocean opportunity for itself, having also other competitors in this new market, nor a red ocean situation, due to its know-how and resources, which are representing an advantage over the new market’s direct competition.

The main purpose of an organization in the Purple Ocean is to survive during difficult times caused by different influencing factors (crises, high competition, political constraints, etc).

Figure 1 hypothetically exemplifies the three situations in which two competing organizations may find themselves. In the Red Ocean situation, the organizations are fighting constantly to gain market share. In this situation, each action of organization O1, at a very short distance has a reaction from its direct competitor O2.

In the Blue Ocean strategic situation, in most cases, technology producers or IT organizations (O1) are launching an innovating product that creates a new market. In this case, the competitor (O2) takes longer time to launch a similar product or service to compete with the pioneers, but eventually it happens. When the competitor (O2) is following the path of the initiator (O1), both organizations eventually fall into the Red Ocean.

The third situation is represented by the proposed Purple Ocean. In this case, an organization (O3), which is at some point in the Red Ocean, is launching one or more different products from its core business in order to diversify its activity and to adapt to the constantly changing market. In this case, the organization does not get distracted from its core activity but, reorients itself towards new opportunities, using the know-how and resources it already has. Usually, it is using one or more models which are described by Bonie and Joseph (2019). Moreover, the organization’s competitors O1 and O2 are now competing on a single market with O3, while O3 diversifies its products on different markets, using its resources and know-how as competitive advantage.

Conclusions and Managerial Implications

Proposing the novel concept of “purple ocean”, this paper has a provocative role, which is to raise the awareness of scholars, managers and professional consultants on a particular situation of Blue Ocean strategy (called “Purple Ocean”). It is worth noting that the “purple ocean” is not a different strategy (other than the Blue Ocean); it just defines a particular strategic situation, frequently faced in the real world.

This situation is expected to take place in the real business world more frequently during the current turbulent times. Therefore, the managerial implications are important for scholars, researchers, professional business services providers, practitioners, strategy makers and top business managers.

Nonetheless, this paper fills in a gap of scarce literature on this subject, particularly in Romania.

Limitations and Further Research

Since the case described was just aimed to provide a practical illustration of the strategic situation called “Purple Ocean”, it did not provide a detailed analysis of the transition process of the company from blue-to-purple, over time. Therefore, a deeper and finer analysis, that would unveil the root causes, describe the evolutionary path, and provide fair explanations for the results of the case situation, might be a further research path.

Being an article on the subject of this peculiarity of applying the theory of Blue Ocean Strategy in practical situations, it has inherent limitations. More cases should be investigated, in more industries, and in more countries.

Note

This article is an updated version of the paper “The Blue Ocean Strategy Revisited: What Color Will the Ocean Be Tomorrow?” presented at the 37th IBIMA (International Business Information Management Association) virtual International Conference (scheduled on 1-2 April 2021, initially in Cordoba, Spain), published in Conference Proceedings. ISBN: 978-0-9998551-6-4.

References

- Abegglen, J.C., Stalk, Jr., G. (1985) Kaisha, The Japanese Corporation. New York, USA: Basic Books, Inc.

- Ansoff, H.I. (1965) Corporate Strategy. An Analytic Approach to Business policy for Growth and Expansion. New York: McGraw-Hill

- Ansoff, H.I. (1979) Strategic Management. London, UK: Palgrave MacMillan

- Ansoff, H.I. (1987) Strategic Management of Technology. IEEE Engineering Management Review, 15(3), 2-13.

- Ansoff, I. (1988) The New Corporate Strategy. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons.

- Ansoff, I. (1991) Critique of Henry Mintzberg’s The design school: reconsidering the basic premises of strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 12(6), 449-461.

- Ansoff, H.I., McDonnel, E.J. (2008) Implanting Strategic Management. Second Edition. New York: Prentice Hall

- Ansoff, H.I., Kipley, D., Lewis, A., Helm-Stevens, R., Ansoff, R. (2019) Implanting Strategic Management. Third Edition. London, UK: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Ansoff, H.I, Antoniou, P.H. (2006) The Secrets of Strategic Management: The Ansoffian Approach. BookSurge Publishing. First published by Ansoff Institute in 2005.

- Bindra Gupta, S., Parameswar, N. and Dhir, S. (2019) Strategic management: The evolution of the field, Strategic Change, 28(1), 469–478.

- Boni, A. and Joseph, D. (2019) Four Models for Corporate Transformative, Open Innovation. Journal of Commercial Biotechnology, 24(4), 23-31.

- Bonsu, S. (2019) Strategic Management: The Concept of Competing with Self. Journal of Marketing and Management, 10(2), 20-44.

- Chandler, A.-Jr. (1962) Strategy and Structure: Chapters in the History of the American Industrial Enterprise. Cambridge, MA, USA: The Massachusetts Institute of Technology – MIT Press.

- Christensen, C.M., Raynor, M. and McDonald, R. (2015) What Is Disruptive Innovation? Harvard Business Review, December 2015, 44-53.

- Daimler (2009) Car2go: Daimler’s new concept for individual urban mobility.[Online] [Retrieved 28 February 2021] from: https://media.daimler.com/marsMediaSite/en/instance/ko/car2go-Daimlers-new-concept-for-individual-urban-mobility.xhtml?oid=9904342

- Doer, J. (2018) Measure What Matters. How Google, Bono, and the Gates Foundation Rock the World with OKRs. New York, USA: Bennett Group, LLC.

- Drucker, P. (1954) The Practice of Management. New York: Harper & Brothers.

- Drucker, P. (1964) Managing for Results. New York: Harper & Row.

- Drucker, P. (1971) Drucker on Management. London: Management Publications Limited.

- Drucker, P. (1980) Managing in Turbulent Times. New York: Harper & Row.

- Drucker, P. (1985) Innovation and Entrepreneurship. New York: Harper & Row.

- Drucker, P. (1995) Managing in a Time of Great Change. New York: Truman Talley Books/Dutton.

- Fayol, H. (1917) Administration industrielle et générale; prévoyance, organisation, commandement, coordination, contrôle. Paris: H. Dunod et E. Pinat.

- Gantt, H.L. (1916) Industrial Leadership. New Haven: Yale University Press

- Hamel, G.P., Prahalad, C.K. (1994) Competing for the Future. Boston, MA, USA: Harvard Business School Press.

- Hill, C.W.L., Jones, G.R. (1989) Strategic Management. An Integrated Approach. Boston, MA, USA: Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Hitt, M.A., Ireland, R.D., Hoskisson, R.E. (2017) Strategic Management: Competitiveness & Globalization: Concepts and Cases. 12th edition. Boston, MA, USA: CENGAGE Learning.

- Hussey, D. (1998) Strategic Management. From theory to implementation. Fourth Edition. Oxford, UK: Butterworth-Heinemann. First Edition published by Pergamon Press, in 1974.

- Hussey, D. (1999) Igor Ansoff’s continuing contribution to strategic management. Strategic Change, 8(7), 375-392.

- Jeffs, C. (2008) Strategic Management. 1st edition. London, UK: SAGE Publications.

- Kaplan, R.S., Norton, D.P. (2001) The Strategy-Focused Organization. How Balanced Scorecard Companies Thrive in the New Business Environment. Boston, MA, USA: Harvard Business School Press.

- Kazmi, A. and Kazmi, A. (1992) Strategic Management. 1st edition. New York, USA: McGraw-Hill Education.

- Kim, W.C., Mauborgne, R. (2004) Blue Ocean Strategy. Harvard Business Review, 82(10), November 2004, 76-84. October 2004, Reprint R0410D.

- Kim, W.C., Mauborgne, R. (2004) Blue Ocean Strategy. How to Create Uncontested Market Space and Make the Competition Irrelevant. Boston, MA, USA: Harvard Business Review Press.

- Kim, W.C., Mauborgne, R. (2017) Blue Ocean Shift. Beyond Competing – Proven Steps to Inspire Confidence and Seize New Growth. London, UK: Pan MacMillan.

- Kotler, P. (1967) Marketing Management: Analysis, Planning and Control. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA: Prentice Hall.

- Kumar, N. (2004) Marketing as Strategy: Understanding the CEO’s Agenda for Driving Growth and Innovation. Boston, MA, USA: Harvard Business School Press.

- Levinthal, D. and March, J. (1993) The Myopia of Learning. Strategic Management Journal, 14(1), 95-112.

- Loveridge, D. (2003) Foresight: The Art and Science of Anticipating the Future. Milton Park, UK: Taylor and Francis.

- Lynch, R. (2018) Strategic Management. 8th edition. London, UK: Pearson Education.

- Maier, D., Maftei, M., Maier, A. and Bițan, G.E. (2019) A Review of Product Innovation Management Literature in the Context of Organization Sustainable Development. Amfiteatru Economic, 21(13), 816-829.

- Martinet, A.-C. (2010) Strategic planning, strategic management, strategic foresight: The seminal work of H. Igor Ansoff. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 77(9), 1485-1487.

- Melendez, K., Dávila, A. and Melgar, A. (2019) Literature Review of the Measurement in the Innovation Management. Journal of Technology Management & Innovation, 14(2), 81-87.

- Mintzberg, H. (1987) The Strategy Concept I: Five Ps for Strategy. California Management Review, 30(1), 11-24.

- Mintzberg, H. (1994) The Rise and Fall of Strategic Planning. Harvard Business Review, January-February 1994, 107-114.

- Mintzberg, H. (2013) The Rise and Fall of Strategic Planning. New York: The Free Press.

- Mintzberg, H., Ahlstrand, B.B., Lampel, J. (1998) Strategy Safari: A Guided Tour through the Wilds of Strategic Management. New York: The Free Press.

- Moussetis, R. (2011) Ansoff revisited. How Ansoff interfaces with both the planning and learning schools of thought in strategy. Journal of Management History, 17(1), 102-125.

- Nickols, F. (2016a) Three Forms of Strategy: General, Corporate & Competitive. [Online] Distance Consulting. [Retrieved 15 February 2021] from: https://www.nickols.us/three_forms.pdf

- Nickols, F. (2016b) Strategy, Strategic Management, Strategic Planning and Strategic Thinking. [Online] Distance Consulting. [Retrieved 15 February 2021] from: https://www.nickols.us/strategy_etc.pdf

- Osterwalder, A. (2004) The business model ontology: A proposition in a design science approach. PhD thesis. Université de Lausanne – Ecole des Hautes Études Commerciales.

- Osterwalder, A., Pigneur, Y. (2002) An eBusiness Model Ontology for Modeling eBusiness. 15e Bled Electronic Commerce Conference – eReality: Constructing the eEconomy. Bled, Slovenia, June 17-19.

- Osterwalder, A., Pigneur, Y. (2010) Business Model Generation: A Handbook for Visionaires, Game Changers, and Challengers. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Partridge, L. and Sinclair-Hunt, M. (2005) Strategic Management. 21st edition.Beaconsfield, UK: Selected Knowledge.

- Pearce, J.A. II, Robinson, Jr., R.B. (1982) Strategic Management. Strategy Formulation and Implementation. Homewood, IL, USA: Richard D. Irwin, Inc.

- Popper, R. (2008) Foresight Methodology. In The Handbook of Technology Foresight – Concepts and Practices (Editors: Luke Georghiou, Jennifer Cassingena Harper, Michael Keenan, Ian Miles, and Rafael Popper), 44-88. Chelteham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Porter, M. (1986) Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors. Boston, MA, USA: Harvard Business School Press.

- Porter, M. (1996) What is Strategy? Harvard Business Review, 74(6), November-December 1996, 61-78.

- Scarlat, C., Şişu, M. (2016) B2X marketing approach in a new international firm: Between B2C and B2B. The 18th Eurasia Business and Economics Society – EBES International Conference, January 8-10, 2016. Sharjah, United Arab Emirates. Book of Abstracts, p.33. Published by: Filmon Baskɪ, Ҫözűmleri, A.Ş., Istanbul, Turkey, in December 2015.

- Shekhar, V. (2009) Perspectives in Strategic Management. A Critique of Strategy Safari: The Complete Guide Through the Wilds of Strategic Management. ICFAI Journal of Business Strategy, 6(2), 43-55.

- Steiner, G. (1979) Strategic Planning. New York: The Free Press.

- Şişu, M. and Scarlat, C. (2019) Novel approach in managing international business: B2X business transaction. A Romanian experience. Proceedings of the International Conference on Management and Information Systems – ICMIS, September 29-30, 2019, Bangkok, Thailand.

- Şişu, M. and Scarlat, C. (2020) Entrepreneurial behaviour: Strategic changes and initiatives of the SMEs, members of an international group. FAIMA Business & Management Journal, 8(4), 19-32.

- Taleb, N.N. (2007) The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable. New York: Random House Publishing Group.

- Taleb, N.N. (2012) Antifragile. Things that Gain from Disorder. New York: Random House.

- Taylor, F.W. (1911) The Principles of Scientific Management. New York, USA and London, UK: Harper & Brothers.

- Thompson, Jr. A.A., Strickland III, A.J. (1983) Strategy Formulation and Implementation. Revised Edition. Plano, TX, USA: Business Publications, Inc.

- Tregoe, B., Zimmerman, J. (1980) Top Management Strategy. New York: Simon and Schuster