Introduction

A new product is an output of new product development process that encompasses creative actions (e.g. Anderson, Potočnik and Zhou, 2014; Huang, 2020; Han, Forbes and Schaefer, 2021; Park and Suzuki, 2021). Every outcome of this kind of action is defined by its novelty and meaningfulness (Amabile and Pratt, 2016). Therefore, these two dimensions describe new product creativity (Kim, Im and Slater, 2013; Deng et al., 2021; Yi, Amenuvor and Boateng, 2021). Consequently, a new product is novel or unique to some extent and, at the same time, appropriate or useful for potential buyers. It is thought that both these dimensions are important and necessary attributes of a new product (Im, Montoya and Workman, 2013; Chuang, Morgan and Robson, 2015; Huang, 2020). On the one hand, a new product with a high level of novelty stands out from the competition and can thus be noticed easily. On the other hand, a new product with a high level of meaningfulness is considered appropriate as it strongly appeals to customer needs. Both dimensions are shaped by companies’ product development efforts and, therefore, can be controlled.

This situation calls researchers to investigate the impact of a new product’s novelty and meaningfulness on its performance. It has already been shown that new product meaningfulness is positively related to new product outcomes (Im and Workman, 2004; Bicen, Kamarudin and Johnson, 2014; Chang, Hung and Lin, 2014; Nakata et al., 2018). However, in the case of new product novelty, the research results are mixed. Some scholars find a positive relationship between this dimension and new product performance (Bicen, Kamarudin and Johnson, 2014; Chang, Hung and Lin, 2014), while others report no statistical connection (Im and Workman, 2004; Calantone, Chan and Cui, 2006). However, despite the growing attention to new product creativity, the current literature focuses mainly on studying the impact of each dimension separately. As a result, little is known about their relative influence on new product performance by comparing the effect of each of these dimensions on new product performance.

Further, the next overlooked issue in the stream of new product creativity studies is the influence of external conditions on the relation between new product creativity dimensions and its performance. One of these external factors is market turbulence that is likely to impact this relation. Especially the novelty seems to function in different ways under different levels of market turbulence. It seems that markets with high turbulence require strong attention of buyers to the product and, therefore, higher visibility than in markets with low turbulence. One of the ways to draw buyers’ attention to the product is to shape its novelty dimension appropriately. Therefore, the product newness might have a different role in highly turbulent markets than in stable markets from a new product performance perspective. Thus, this work undertakes the issue of moderating effect of market turbulence on the relation between product novelty and commercial performance.

Building on the resource-based view (RBV) of the firm and signaling theory, we aim to advance the understanding of the effects of the new product creativity dimensions on its performance. RBV explains why firms benefit from a creative new product to achieve planned goals. The signaling theory provides insights into the different ways of functioning of the novelty dimension of new products in stable and turbulent markets. Following recommendations by Stewart and Zinkhan (2006), we integrate RBV and signaling theory to develop a framework to explore: 1) the impact of the dimensions of the creative new product on its commercial performance; 2) the relative influence of these dimensions on the new product performance; and 3) the moderating effect of market turbulence on the relationship between new product novelty and commercial performance.

Our study provides the following contribution to the literature. First, we extend the previous works on the effects of the dimensions of new product creativity (Im, Montoya and Workman, 2013; Bicen, Kamarudin and Johnson, 2014; Chang, Hung and Lin, 2014; Nakata et al., 2018; Zuo, Fisher and Yang, 2019) by comparing the impact strength of new product novelty on its performance with meaningfulness impact strength on its performance. We contribute to new product creativity literature by showing that each dimension of new product creativity affects the product’s commercial performance with different strength.

Second, we investigate the role of market turbulence to understand the conditions that may influence the impact of new product novelty on its performance. In this way we respond to the call of researchers as Bstieler (2005), MacCormack and Verganti (2003), and Song and Montoya-Weiss (2001), who point to the need for further research on the impact of external conditions on the results of new products. Despite the general agreement that the external environment should be included in research on new product development, the environmental factors have been largely ignored as moderating variables of new product performance (Bstieler, 2005). Thus, we investigate the contextual effect of market turbulence on the relationship between new product novelty and commercial performance. Therefore, we contribute to the literature and practice by identifying market conditions that enhance this relationship.

Conceptual Background

The classic definition of creativity, provided by Stein, states that “The creative work is a novel work that is accepted as tenable or useful or satisfying by a group in some point in time” (Stein, 1953 p. 311). According to this definition, creativity is a process that leads to a new and useful outcome, and the latter could be anything, a work of a painter, car designer, or scientist. However, in the context of an organization, creativity is seen as “the production of novel and useful ideas by an individual or small group of people working together” (Amabile and Pratt, 2016 p. 158). Hence, in this view, the outcome of creative work is still new and valuable but limited to an idea. This restriction is based on viewing creativity as an antecedent of innovation in an organization (Stock and Zacharias, 2013; Anderson, Potočnik and Zhou, 2014) because innovation is meant as “the successful implementation of creative ideas within an organization” (Amabile and Pratt, 2016 p. 158). Therefore, creativity and innovation are linked activities as creative work generates novel and useful ideas, whereas innovation is their successful implementation in an organization. However, some authors argue that creativity occurs not just at the beginning of the innovation process, as creativity and innovation are instead a cyclical, recursive process of idea generation and implementation (Paulus, 2002; Anderson, Potočnik and Zhou, 2014).

In a company, one of the important outcomes of creativity and innovation is a new product. According to both definitions of creativity – provided by Stein (Stein, 1953) and Amabile and Pratt (Amabile and Pratt, 2016) – a new product can be considered creative if it features both novelty and usefulness. The latter dimension is also called meaningfulness because a product’s usefulness is expressed as meaningful benefits offered for customers (Heirati and Siahtiri, 2019). These two dimensions are commonly accepted as distinguishing features of a creative new product (Im, Montoya and Workman, 2013; Kim, Im and Slater, 2013; Stock and Zacharias, 2013; Nakata et al., 2018; Selmi and Chaney, 2018; Xu, 2020; e.g. Deng et al., 2021; Yi, Amenuvor and Boateng, 2021). The first dimension, i.e., novelty, reflects the uniqueness, originality, or newness of ideas incorporated in it. In contrast, the second one, i.e., meaningfulness, concerns usefulness, appropriateness, or meaningful benefits of the generated ideas to customers (Kim, Im and Slater, 2013). Therefore, we define new product creativity as the extent to which a new product offers novel and meaningful benefits to potential buyers compared to competitive products.

Both dimensions of creative new products – meaningfulness and novelty – are considered significant in new product literature because, in the last decade, they have been adopted to capture new product (or service) innovativeness (Stock and Zacharias, 2013; Heirati and Siahtiri, 2019) apart of its creativity. However, mainstream literature tends to consider innovativeness only as the degree of the difference between new and competitive products, but only in terms of the degree of novelty (e.g. Garcia and Calantone, 2002; Szymanski, Kroff and Troy, 2007). However, it was noticed that new products or services that do not provide meaningful benefits to customers would not be competitive in the market (Heirati and Siahtiri, 2019). Therefore, the conceptualization of product innovativeness should be based on both its newness and meaningfulness (Stock and Zacharias, 2013).

The new product outcome considered in this study is product commercial performance – indicating to what extent the new product meets its market and financial goals (Montoya-Weiss and Calantone, 1994) – was selected for two reasons. First, the commercial performance of a new product is a relatively overall assessment as it encompasses both financial and market performance. Second, this performance measure of a new product is determined most likely by both its meaningfulness and novelty (Im, Montoya and Workman, 2013; Kim, Im and Slater, 2013).

According to the RBV, explaining differences in firms’ performance is based on two fundamental assumptions about their resources: the first one is resource heterogeneity, and the second – resource immobility (Barney, 1991; Peteraf, 1993; Barney and Hesterly, 2012). In this view, a product is considered a firm’s tangible asset (Barney and Hesterly, 2012) that meets these two assumptions. With reference to heterogeneity, various companies offer different products. Yet, firms that compete in the same product category do not offer identical goods. The latter differ in attributes like overall benefits provided for customers, quality, appearance, or price. Next – in terms of immobility – these differences among products can last for some time because of, for example, patent protection, scarce resources, and capabilities of competitors, or brand reputation. In consequence, a product can be a valuable and rare resource that, in line with RBV, can be the basis for explaining the different results achieved by various products, even if they represent the same category and are offered in the same market.

The signaling theory is appropriate to describe behaviors of two parties (e.g., organizations, customers) when information asymmetry is present (Connelly et al., 2011). Information asymmetry occurs when the level of information of parties involved in transactions is not equal (Spence, 1973). The essence of this theory is that one party (the sender) that has information reduces the information asymmetry by communicating (or signaling) that information to the second party (the receiver). For signaling to take place, on the one hand, the sender should benefit from some action of the receiver, and on the other hand, the receiver should gain from making a decision based on the signal obtained (Connelly et al., 2011). Spence (1973) developed this theory to study labor markets. Since then, it has been applied in various areas of management when dealing with information asymmetry (Kirmani and Rao, 2000). In the context of this study, the signaling theory is applied to explain how firms use product novelty to draw the attention of customers and signal the existence of innovative products. This situation is particularly apparent in the case of turbulent markets, as they feature a high level of information asymmetry between companies and customers.

Hypothesis Development

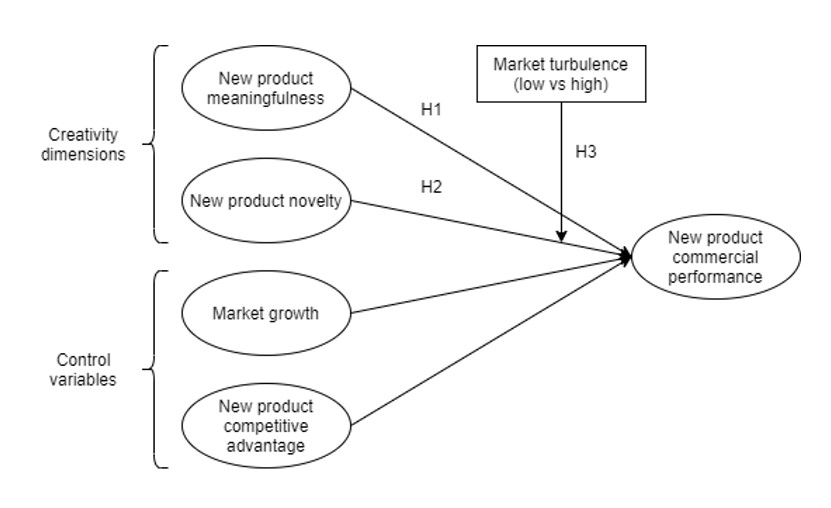

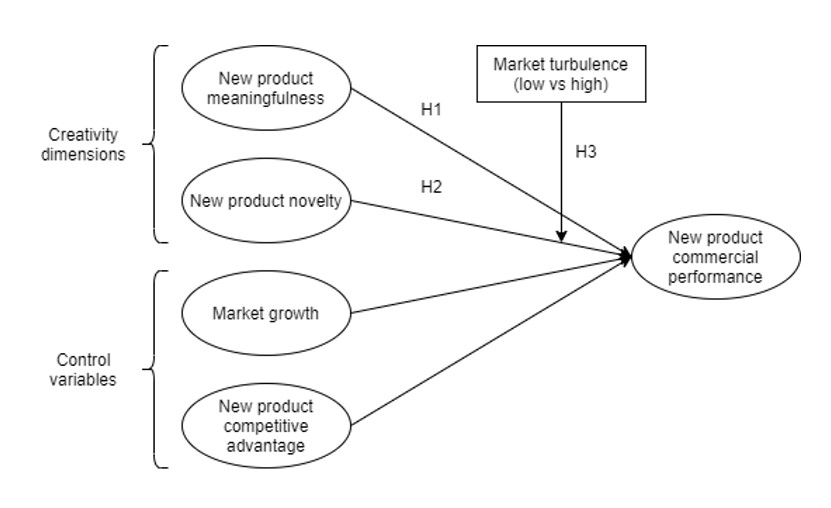

We developed a theoretical framework (Figure 1) to examine the independent effects of new product creativity dimensions, i.e., novelty and meaningfulness, on its commercial performance and to investigate market conditions under which a specific level of new product novelty is beneficial. We argue that each new product creativity dimension positively affects its commercial performance, but the novelty effect is contingent on market turbulence.

It is expected that new product meaningfulness positively impacts its commercial performance. Meaningfulness is a necessary and key dimension of any product. The modern marketing theory assumes that the buyer does not want a product but the satisfaction of the needs by obtaining meaningful benefits (Kotler and Keller, 2016). This dimension relates directly to product usefulness for buyers or its appropriateness to their needs and expectations. The latter, on the other hand, are growing and have no upper limit. Consequently, the higher the ability of a product to meet the needs of buyers, both expressed and latent, the higher the level of perceived benefits offered by the product to customers. And with the growth of the latter, the buyer surplus (Peteraf and Barney, 2003) and the willingness to buy the product grow. These arguments support the positive link between the dimension of meaningfulness and the product commercial results. Such a positive relationship was also posited in other works (Im and Workman, 2004; e.g. Bicen, Kamarudin and Johnson, 2014). Therefore, the following research hypothesis was formulated:

H1: New product meaningfulness positively affects its commercial performance.

Figure 1: Theoretical framework

The impact of new product novelty on its commercial performance is likely to be dual. On the one hand, it is believed that novelty is a necessary attribute of a new product and supports its performance for the following reasons. First, novelty is needed to draw attention and generate the initial interest of potential customers (Nakata et al., 2018). In this way, the supplier differentiates its new product from competitive offerings as unique products are more easily noticeable by buyers. Second, customers tend to view the novelty of a new product as a proxy of additional benefit for them because they assume that the supplier improves attributes or extends the benefit connected to the product (Xu, 2020). Thus, product novelty is likely to be synonymous with its value from the buyers’ perspective. According to the signaling theory, by underlying the novelty of a new product, the manufacturer sends a noticeable signal to potential buyers that innovative products offer unique benefits. Third, novelty exhibits product uniqueness or differentiation which increases the difficulty for competitors to imitate or substitute it (Zuo, Fisher and Yang, 2019). Therefore, developing a unique product is one way to create a resource with limited mobility according to the RBV (Barney, 1991). All these arguments suggest that the novelty of a new product increases its commercial success.

However, on the other hand, Nakata et al. (2018) note that the increase in product novelty increases the level of unfamiliarity with the product for buyers. In this view, in the case of very novel products, unfamiliarity with the product for buyers may be so high that it harms its commercial performance. Nonetheless, the problem of this adverse effect is neither new nor unknown to new product professionals, so they are likely to keep it under control. Therefore, we follow the positive view of the relationship between new product novelty and its commercial performance and posit that:

H2: New product novelty positively affects its commercial performance.

It is worth comparing how strongly each dimension of a creative new product affects its commercial performance because we can thus determine which of these dimensions plays a more significant role in achieving this result. However, it is yet to be tested whether the strengths of the two effects differ. In this regard, we expect that the meaningfulness of a new product influences its commercial performance more strongly than its novelty. This is because meaningfulness – a dimension that represents the level of meaningful benefits the product offers to buyers – directly relates to the total perceived benefits of the product, which, in turn, determines its economic value and customer surplus (Peteraf and Barney, 2003). The second dimension considered – namely novelty – can also contribute to these total benefits; however, by its nature, to a lesser extent than meaningfulness. Therefore, we posit that:

H3: New product meaningfulness affects its commercial performance more than its novelty.

This study assumes that the hypothesized relationship between new product novelty and its commercial performance (hypothesis H2) is contingent upon varying degrees of market turbulence. External factors are important in developing new products as they determine their creation and subsequent functioning on the market. Among them, market turbulence seems to be one of the factors that should be taken into account when shaping the creative dimensions. Following Jaworski and Kohli (1993), this study considers market turbulence as a frequent change in market demand, customer needs and preferences, and the market structure that cause customers to look for new products. Low market turbulence means that the market is predictable and static, whereas high turbulence concerns unpredictable and dynamic markets. Therefore, information asymmetry between suppliers and customers is likely higher in highly turbulent markets than in those with low turbulence. The signaling theory implies that in such markets, a supplier should send a clear signal for customers – who sometimes are new on the market – that product innovation has been launched. This can be done by increasing the novelty dimension, so the product is well distinguished and recognized under changing market conditions. Conversely, developing product newness is not necessarily due to a situation of low market turbulence because customers know and identify suppliers and their offers. Thus, a moderating effect of market turbulence on the relationship is expected, and we posit that:

H4: Market turbulence moderates the relationship between product novelty and its commercial performance such that this association is stronger when market turbulence is high compared to when it is low.

We did not find any substantial argument that the connection between new product meaningfulness and commercial performance could be contingent on market turbulence. Therefore, we do not posit an analogous hypothesis to H4 concerning meaningfulness.

Methods

Sample and Procedure

To gather data, we performed a cross-sectional mail survey among high- and medium-high-technology companies in Poland employing more than 49 people, as these firms are quite heavily involved in new product development (Dmitrowicz-Życka et al., 2019). According to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) classification, which is based on direct R&D intensity and the R&D embodied in intermediate and investment goods (Hatzichronoglou, 1997), industrial sectors and manufacturers fall into four groups: high, medium-high, medium-low, and low technology. The first two groups were chosen for this study because they represent industries with higher technological intensities than the last two. The high-technology group includes the pharmaceutical, computers and electronics, and aerospace sectors; the medium-high-technology group contains the chemical, weapons and ammunition, industrial electrical machinery, machinery and equipment, automotive, other transport equipment, and medical and dental equipment industries. Furthermore, this study focuses on firms that employ more than 49 people as such companies are involved in new product development to a greater extent than smaller firms (Dmitrowicz-Życka et al., 2019).

A sampling frame of Polish high and medium-high-technology companies employing more than 49 people was obtained from the HBI directory of Polish firms. It was used to randomly select 1,450 companies – due to budget constraints – that were asked to participate in our mail survey. As a result, the questionnaire and a cover letter were sent to the person in the highest-ranked position in each company, e.g., a managing director. We asked this person to choose a new product launched at least six months earlier and to forward the questionnaire to the person involved in this project, such as R&D, marketing, or engineering professionals. We also offered a research report as an incentive for companies that sent back completed questionnaires. In addition, two follow-up letters were sent to increase the response rate. In total, after discarding incorrect questionnaires, we received 374 usable questionnaires, which yielded a rate of return of 25.8%.

We compared both early and late respondents to assess any non-response bias (Armstrong and Overton, 1977) and subsequently examined the means for all constructs of interest through a t-test. This analysis showed no significant differences in the mean for all constructs (p <0.05), thus proving that no such bias exists.

Company size and industry type were used to describe the final sample. In terms of company size, the sample structure was as follows: 75.9% of firms employed 50 to 250 people, 20.1% employed 250 to 999 people, and 4.0% had more than 999 employees. In addition, the sample included the following proportions regarding industry type: machinery and equipment – 32.1%, industrial electrical machinery – 16.0%, motor vehicles – 15.2%, chemicals and chemical products – 14.2%, computer and electronic products – 10.4%, pharmaceutical products – 4.3%, other transport equipment – 2.9%, medical and dental products – 2.7%, air and spacecraft machinery – 1.3%, and weapons and ammunition – 0.8%.

Measures

All constructs were measured with established items in the literature. As used in a previous study (Im, Montoya and Workman, 2013), each of the two dimensions of new product creativity – meaningfulness and novelty – was measured with a four-item scale. In addition, its commercial performance was operationalized through four items chosen from Hultink et al. (2011) and Dabrowski (2018).

Two variables that commonly influence new product commercial performance were used as control variables: market growth and product competitive advantage. Market growth, understood as an increase in market demand and market attractiveness for future growth, was measured with three items from (Parry and Song, 2010). Product competitive advantage means that customers perceive greater value in a firm’s product, and they are willing to shift their purchases away from rivals (Im, Montoya and Workman, 2013). This variable was measured with four items selected from (Atuahene-Gima, 1995; Im, Montoya and Workman, 2013). Additionally, we measured market turbulence that was used in the model as a moderating variable. Market turbulence is defined as the rate of market changes, especially in the range of customers’ needs and preferences, and was measured by four items selected from (Jaworski and Kohli, 1993).

We measured all items used in the constructs on seven-point Likert-type scales.

Data Analysis

Following Anderson and Gerbing (1988), the data were analyzed in two steps. First, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to test the measurement model, followed by structural equation modeling (SEM) to verify the multiple regression model for latent variables using Mplus v.8.1 statistical software. This software provides a mean-adjusted maximum likelihood estimator (MLM), used in both CFA and SEM, resistant to data non-normality (Muthén, Muthén and Asparouhov, 2016). Next, we applied SEM because it is generally considered as the standard method to examine the regressions between latent variables (Devlieger, Mayer and Rosseel, 2016).

To test hypotheses H1–H3, we verified a multiple regression model for latent variables, in which a dependent variable was the new product commercial performance, and independent variables were two dimensions of the creative new product – novelty and meaningfulness – and two control variables, i.e., market growth and product competitive advantage.

To test hypothesis H4, we applied a two-group analysis based on the multiple regression model, where a grouping variable was a dichotomous variable of market turbulence. The latter variable was created on the basis of the four items used to measure market turbulence. These four items were reduced by performing the principal component analysis (PCA) to one component that explained 63.5% of the total variance. Next, the median of this component was calculated, and the sample was divided into two groups based on its value. Units with values below the median were in the group with low market turbulence, while those with values higher than the median were grouped as high market turbulence. Thus, the sample of 374 units was split into two groups of 187 units each, based on the dichotomous variable of market turbulence. In addition, before performing the two-group analysis, we used the multigroup confirmatory factor analysis (MGCFA) to test measurement invariance in the two groups (Brown, 2015).

Thus far, no consensus has been reached regarding the recommended sample size for structural equation modeling (SEM). However, a sample of 374 units can be viewed as adequate for this research concerning model complexity (i.e., five constructs) and essential characteristics (Bentler and Chou, 1987).

Results

Measurement Model and Measurement Invariance

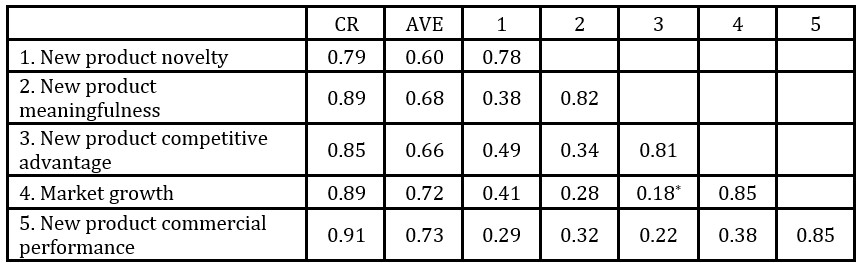

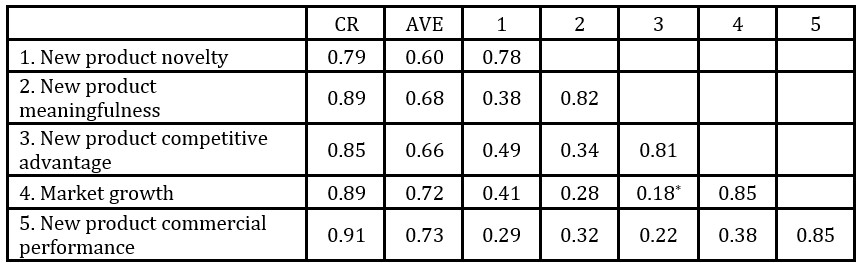

The CFA involved five constructs included in the multiple regression model. The initial analysis led to the elimination of one item representing competitive advantage (“not at all cost-effective” versus “highly cost-effective”), but other items were retained. The measurement model provided an acceptable fit to the data: χ2 (125) = 275.140, p <0.001, χ2/df = 2.20, RMSEA = 0.057, SRMR = 0.045, CFI = 0.958, and TLI = 0.949. We applied a chi-square test to evaluate the model’s fit. However, it has certain limitations, such as sample size sensitivity (West, Taylor and Wu, 2012). Thus, other fit indices were used to evaluate the model (West, Taylor and Wu, 2012) as recommended for the MLM estimator. The latter indices met the standards necessary for an acceptable fit: a CFI (comparative fit index) value of 0.95 or higher, an RMSEA (root mean square error of approximation) value of 0.06 or less, an SRMR (standardized root mean square residual) value of 0.08 or less, as well as an χ2/df value of 5 or less (Hu and Bentler, 1999; West, Taylor and Wu, 2012). However, the required standard for a TLI (Tucker-Lewis index) value of 0.95 was not met (Hu and Bentler, 1999), but the difference between the TLI score (0.949) and this standard was so minor that it was assumed that the fit of the measurement model to the data is acceptable. The estimates of the standardized factor loadings of all items are significant, as recommended (Brown and Moore, 2012), and they exceed 0.64. As indicated in Table 1, the average variance extracted (AVE) is greater than the required standard of 0.5 (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). Altogether, these outcomes indicate an adequate convergent validity of the measurement model.

Table 1: Construct correlations and discriminant validity

Note: Off-diagonal: construct correlations; along-diagonal: square root of the AVE; * p < 0.01 and all other correlations are significant at p < 0.001; CR – Construct reliability; AVE – Average variance extracted.

Table 1 demonstrates the construct reliability (CR), and all CR values exceed the critical value of 0.7 (Bagozzi and Yi, 2012). Table 2 also shows the construct correlations and the square root of the AVE. In line with Fornell and Larcker (1981), the constructs demonstrate discriminant validity because the square root of the AVE for each factor is greater than the highest correlation between the factors involving the focal factor.

Common method variance (CMV) may affect the correlations of the variables considered, as they were simultaneously measured using a single instrument (Malhotra, Schaller and Patil, 2017). We controlled the CMV using both procedural and statistical techniques. The procedural remedies consisted of ensuring respondents’ anonymity, reducing item ambiguity, improving the items’ wording, and placing constructs in different sections. Regarding the statistical techniques, we tested Harman’s single-factor model using CFA to demonstrate that this model fit the data poorly: χ2 (135) = 2,294.951, p <0.0001, RMSEA = 0.207, CFI = 0.400, TLI = 0.320, and SRMR = 0.154. These results show that a one-factor model is not acceptable and that CMV is unlikely to be a problem.

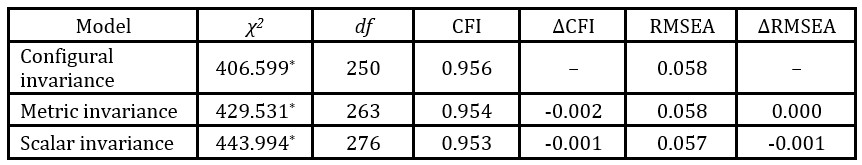

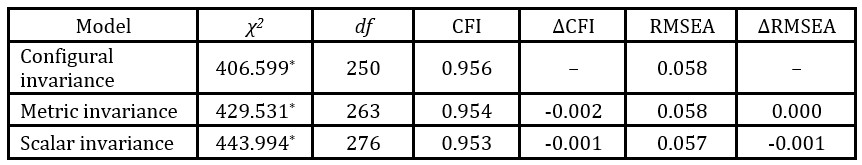

The next important issue related to measurement is testing the invariance of the measurement scales across groups of low and high market turbulence. Vandenberg and Lance (2000) proposed testing measurement invariance by comparing hierarchically nested models: configural, metric, and scalar. The first one requires each construct to be measured by the same items. The second model also assumes equality of factor loadings across compared groups. And the third one also requires equality of indicator intercepts (Brown, 2015). Meade et al. (2008) proposed to test measurement invariance by comparing scores of two fit measures, namely CFI and REMSA. According to this rule, an assumption about measurement invariance can be rejected if a difference (Δ) between more and less restricted models is smaller than 0.002 for CFI and greater than 0.007 for RMSEA. Mplus v.8.1 was used to test measurement invariance as the tests of equal form, equal factor loadings, and equal intercepts can be performed by a single command (Brown, 2015). The MGCFA results presented in Table 2 show scalar measurement equivalence across low and high market turbulence groups. The assumption concerning measurement invariance may not be rejected because the difference ΔCFI is not smaller than -0.002 and the difference ΔRMSEA is greater than 0.007 (Table 2).

Table 2: Fit measures of models used for testing multigroup measurement invariance

Note: * p < 0.0001

Hypothesis Testing

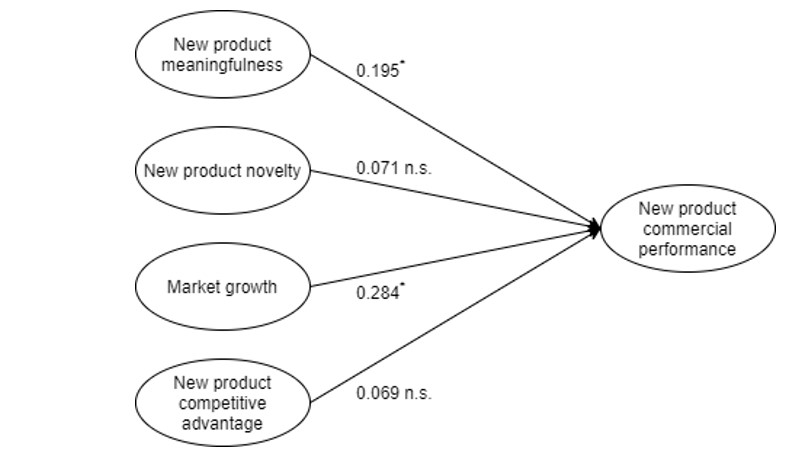

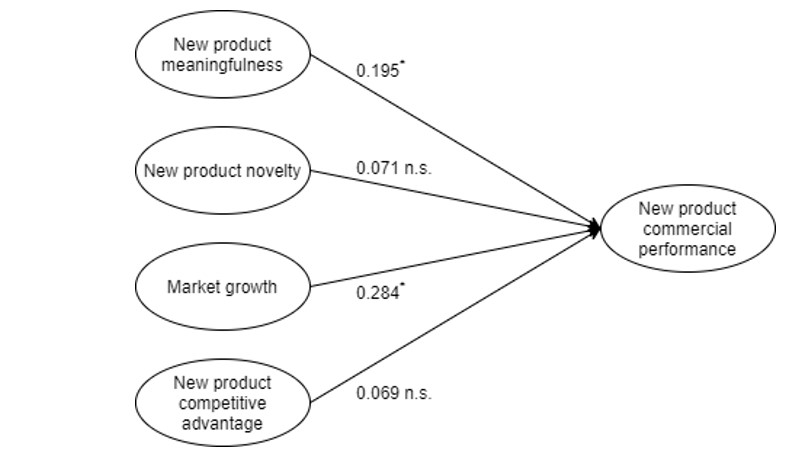

Figure 2 illustrates the multiple regression model of the new product novelty and meaningfulness, its commercial performance as well as the estimated effects, which provided an acceptable model fit: χ2 (125) = 275.140, p <0.001, χ2/df = 2.20, RMSEA = 0.057, SRMR = 0.045, CFI = 0.958, and TLI = 0.949.

Figure 2: Estimation of the multiple regression model

Note: Standardized values; * p < 0.001; n.s. indicates statistical insignificance at p > 0.05.

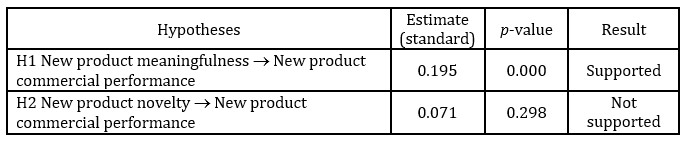

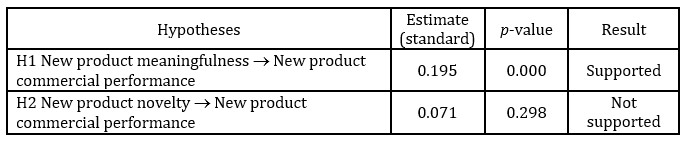

Table 3 presents the test results for hypotheses H1 and H2. An examination of effects reveals a positive relationship between new product meaningfulness and its commercial performance (β = 0.195, p <0.001), whereas, contrary to expectations, such a relationship between its newness and commercial performance was not observed (β = 0.071, p >0.05). These findings support hypothesis H1 but not H2. Regarding the relationships between the control variables and new product commercial performance, market growth had a significant positive effect on its commercial success (β = 0.284, p < 0.001). Yet, such a link between new product competitive advantage and its commercial performance was not significant (β = 0.069, p >0.05). The model explained approximately 20.7% of the variance in new product commercial performance, as the coefficient of determination (R2) was 0.207 for this construct.

To verify hypothesis H3, the effect of new product meaningfulness on its commercial performance was compared to the effect of new product novelty on its commercial performance. The result of the Wald chi-square test revealed that these effects are not equal (χ2 (1) = 4.220, p <0.05). However, as both effects were positive, it was concluded that the first effect (i.e., the influence of new product meaningfulness on its commercial performance) was stronger than the latter (i.e., the new product novelty to its commercial success). This outcome supports hypothesis H3.

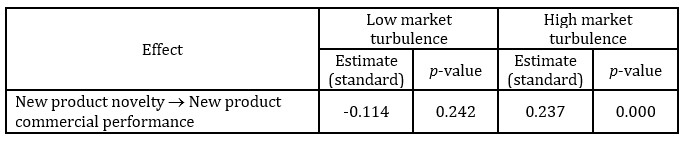

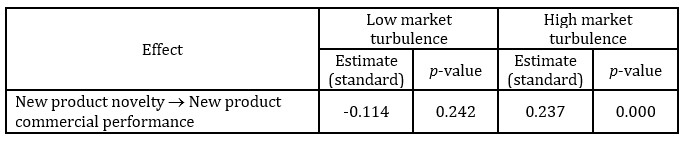

Table 3: Results of testing hypotheses H1 – H2

Regarding hypothesis H4, we compared the effects of new product novelty on its commercial performance across two groups of low and high market turbulence. The estimates of these effects in both groups are shown in Table 4. The Wald chi-square test shows that the effects in both groups are not equal – that is, χ2 (1) = 6.441, p <0.05. As the effect under low market turbulence is negative and not significant (β = -0.114, p >0.05), and the effect under high market turbulence is positive and significant (β = 0.237, p <0.001), it was concluded that the latter effect is more pronounced than the former. Therefore, hypothesis H4 was supported.

Table 4: Effect of a new product’s novelty on its commercial performance under low and high market turbulence

Discussion and Conclusions

The empirical survey results confirmed our expectation of the positive effect of new product meaningfulness on its commercial performance. This relationship is likely due to the fact that when buying a product, buyers look for meaningful benefits to meet their needs. However, the latter does not have an upper limit, so along with the increase in the meaningfulness dimension of the product, one can observe an increase in its commercial results. Furthermore, this kind of influence is confirmed by the results of other studies (Im and Workman, 2004; Bicen, Kamarudin and Johnson, 2014; Chang, Hung and Lin, 2014; Nakata et al., 2018).

Regarding the second dimension of the creative new product, namely its novelty, our results indicate no relationship between this dimension and its commercial results. Although still, in this case, the value of the novelty effect on the new product commercial performance is positive, this effect is not statistically significant. This finding is consistent with the study by (Im and Workman, 2004; Calantone, Chan and Cui, 2006), who also did not observe such an association. Most likely, the reason for it is the dual impact of the novelty on the willingness to buy a new product. As already mentioned, on the one hand, the novelty or originality of a product is the dimension that makes the new product noticeable to buyers and thus positively influences their willingness to buy it. However, on the other hand, originality or unconventionality makes the new product alien to buyers. This dual impact may be the reason for the lack of a linear link between the novelty of a new product and its results. Moreover, the scatter plot analysis between these two variables did not show any curvilinear relationship between them.

This study showed that new product meaningfulness influences its commercial performance more strongly than its novelty under normal market conditions. This might be because the former directly and to a greater extent than the latter relates to the total benefits of the product perceived by customers. In turn, these benefits determine customers’ surplus within this product and, as a consequence, their willingness to buy it.

The next finding of this study concerns the moderating effect of market turbulence on the impact of new product novelty on its commercial performance. The results indicate that in conditions of high market turbulence, the novelty has a stronger impact on performance than when the market turbulence is low. Following the signaling theory, it seems that in high turbulent markets, with quite frequent changes in market demand and customer needs and market structure, the novelty of product innovation is an essential signal from suppliers to potential buyers. This signal might allow potential customers to notice product innovation on the market as the information asymmetry between buyers and suppliers is likely high due to frequent market changes. Hence, the suppliers can use this signal to promote their new product and, in this way, enhance its commercial performance. The other way round, under low market turbulence, when markets are static and predictable, the information asymmetry is likely low, and customers find it relatively easy to notice product innovations. Therefore, it is rather not necessary to escalate the dimension of product innovation novelty due to the aforementioned dual effect of this novelty on product commercial performance.

The theoretical contribution of this study is twofold. First, we revealed that new product meaningfulness affects its commercial performance more than its novelty under normal market conditions. So far – to the best of our knowledge – researchers have not performed this kind of comparison. Our study, based on empirical data, verified the hypothesis that new product meaningfulness has a higher impact than its novelty on commercial results. Second, our work showed that the relationship between the novelty of a new product and its commercial performance is contingent on market turbulence, which has not been studied so far. In this regard, our study suggests that market turbulence is likely to moderate the relationship between product novelty and its commercial performance. Moreover, this association is stronger when market turbulence is high compared to when it is low.

Our work has some managerial implications. Regarding innovative product meaningfulness or usefulness, we recommend managers develop this dimension of creative new products as much as possible. Our results clearly indicate that it has a positive impact on the novel product performance. Moreover, it influences these results more strongly than the novelty of the product. Our recommendation is also supported by the fact that there is no upper limit to providing meaningful benefits while meeting the needs of buyers. Most likely, one of the significant limitations in this respect is the technological barrier.

However, with regard to the novelty dimension of a new product, our recommendations for NPD managers are related to the level of market turbulence. In conditions of high market turbulence, NPD managers, aiming to achieve a high commercial performance of the new product, should develop this dimension, enabling the product to be distinguished from competing products. Thanks to this distinction, even in conditions of frequent market changes, the new product has a chance to be noticed by buyers and then possibly arouse their interest. However, NPD managers should take into account that the increase in product novelty is related to the increasing unfamiliarity of the product for buyers, and reducing this unfamiliarity by educating buyers about the use of the product may be needed. On the other hand, under low market turbulence, the novelty of product innovation does not appear necessary to obtain high commercial results because buyers have relatively good market recognition in stable environmental conditions. Nevertheless, some level of novelty may be needed to distinguish the new product from competing products.

This study has several limitations, and some of them can be addressed by future research. The first limitation is that our work relies on a cross-sectional data set, which restricts the examination of causal relationships. However, the relationships investigated are based on grounded theories and are substantially supported. The second limitation involves measuring new product commercial performance as a cognitive and perceptual variable. This approach was applied because an objective measure was challenging to obtain from nearly four hundred firms. Therefore, the cognitive and perceptual variable was used as these types of measures highly correlate with objective performance measures (Atuahene-Gima and Li, 2004; Wall et al., 2004). Future studies could consider gathering objective performance data to validate our outcomes. The third limitation refers to the population investigated, namely companies with high R&D intensity (high- and medium-high-technology firms) from one country as the specific context of this group can influence the findings’ generalizability. Thus, future research could study the relationships investigated in other industries and different countries. The fourth limitation is that this study’s model only partially explains the variance in new product commercial performance, and other variables should also be examined. Therefore, future research could examine other independent variables substantially related to new product commercial performance. The fifth limitation is that our work includes only one moderator variable, namely market turbulence. Thus, subsequent research could consider examining other eventual moderators of the phenomenon of interest. One of them could be an organizational climate that seems to be a crucial potential moderator of the effects researched as this climate can support creativity and innovation (Isaksen and Ekvall, 2010).

Bibliography

- Amabile, T. M. and Pratt, M. G. (2016) ‘The dynamic componential model of creativity and innovation in organizations: Making progress, making meaning’, Research in Organizational Behavior. Elsevier Ltd, 36, pp. 157–183. doi: 10.1016/j.riob.2016.10.001.

- Anderson, J. C. and Gerbing, D. W. (1988) ‘Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach’, Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), pp. 411–423. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411.

- Anderson, N., Potočnik, K. and Zhou, J. (2014) ‘Innovation and creativity in organizations: A state-of-the-science review, prospective commentary, and guiding framework’, Journal of Management, 40(5), pp. 1297–1333. doi: doi.org/10.1177/0149206314527128.

- Armstrong, J. S. and Overton, T. S. (1977) ‘Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys’, Journal of Marketing Research, 14(3), p. 396. doi: 10.2307/3150783.

- Atuahene-Gima, K. (1995) ‘An exploratory analysis of the impact of market orientation on new product performance: A contingency approach’, Journal of Product Innovation Management, 12(4), pp. 275–293.

- Atuahene-Gima, K. and Li, H. (2004) ‘Strategic decision comprehensiveness and new product development outcomes in new technology ventures’, Academy of Management Journal, 47(4), pp. 583–597. doi: 10.2307/20159603.

- Bagozzi, R. P. and Yi, Y. (2012) ‘Specification, evaluation, and interpretation of structural equation models’, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40(1), pp. 8–34. doi: 10.1007/s11747-011-0278-x.

- Barney, J. (1991) ‘Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage’, Journal of Management, 17(1), pp. 99–120. doi: 10.1177/014920639101700108.

- Barney, J. and Hesterly, W. (2012) Strategic management and competitive advantage. Concept and cases. 4th ed. Boston MA: Pearson Education.

- Bentler, P. M. and Chou, C. P. (1987) ‘Practical issues in structural modeling’, Sociological Methods & Research, 16(1), pp. 78–117. doi: 10.1177/0049124187016001004.

- Bicen, P., Kamarudin, S. and Johnson, W. H. A. (2014) ‘Validating new product creativity in the eastern context of Malaysia’, Journal of Business Research. Elsevier Inc., 67(1), pp. 2877–2883. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2012.06.007

- Brown, T. A. (2015) Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research. 2nd edn. New York: The Guilford Press.

- Brown, T. A. and Moore, M. T. (2012) ‘Confirmatory factor analysis’, in Hoyle, R. (ed.) Handbook of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford Press, pp. 361–379.

- Bstieler, L. (2005) ‘The moderating effect of environmental uncertainty on new product development and time efficiency’, Journal of Product Innovation Management, 22(3), pp. 267–284. doi: 10.1111/j.0737-6782.2005.00122.x.

- Calantone, R. J., Chan, K. and Cui, A. S. (2006) ‘Decomposing product innovativeness and its effects on new product success’, Journal of Product Innovation Management, 23(5), pp. 408–421. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5885.2006.00213.x.

- Chang, J. J., Hung, K. P. and Lin, M. J. J. (2014) ‘Knowledge creation and new product performance: The role of creativity’, R and D Management, 44(2), pp. 107–123. doi: 10.1111/radm.12043.

- Chuang, F. M., Morgan, R. E. and Robson, M. J. (2015) ‘Customer and competitor insights, new product development competence, and new product creativity: Differential, integrative, and substitution effects’, Journal of Product Innovation Management, 32(2), pp. 175–182. doi: 10.1111/jpim.12174.

- Connelly, B. L. et al. (2011) ‘Signaling theory: A review and assessment’, Journal of Management, 37(1), pp. 39–67. doi: 10.1177/0149206310388419.

- Dabrowski, D. (2018) ‘Sources of market information, its quality and new product financial performance’, Engineering Economics, 29(1). doi: 10.5755/j01.ee.29.1.13405.

- Deng, C. et al. (2021) ‘The double-edged sword impact of effectuation on new product creativity: The moderating role of competitive intensity and firm size’, Journal of Business Research. Elsevier Inc., 137(August), pp. 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.06.047.

- Devlieger, I., Mayer, A. and Rosseel, Y. (2016) ‘Hypothesis testing using factor score regression: A comparison of four methods’, Educational and Psychological Measurement, 76(5), pp. 741–770. doi: 10.1177/0013164415607618.

- Dmitrowicz-Życka, K. et al. (2019) Innovative activity of enterprises in the years 2016–2018. Warsaw.

- Fornell, C. and Larcker, D. F. (1981) ‘Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error’, Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), pp. 39–50. doi: 10.2307/3151312.

- Garcia, R. and Calantone, R. (2002) ‘A critical look at technological innovation typology and inovativeness terminology: a literature review’, Journal of Product Innovation Management, 19, pp. 110–132.

- Han, J., Forbes, H. and Schaefer, D. (2021) ‘An exploration of how creativity, functionality, and aesthetics are related in design’, Research in Engineering Design. Springer London, 32(3), pp. 289–307. doi: 10.1007/s00163-021-00366-9.

- Hatzichronoglou, T. (1997) ‘Revision of the high-technology sector and product classification’, OECD Science, Technology and Industry Working Papers, 1997/02, p. 26. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/134337307632.

- Heirati, N. and Siahtiri, V. (2019) ‘Driving service innovativeness via collaboration with customers and suppliers: Evidence from business-to-business services’, Industrial Marketing Management. Elsevier, 78(November 2017), pp. 6–16. doi: 10.1016/j.indmarman.2017.09.008.

- Hu, L. T. and Bentler, P. M. (1999) ‘Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives’, Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), pp. 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118.

- Huang, J. W. (2020) ‘New product creativity and alliance ambidexterity: the moderating effect of causal ambiguity’, Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing, 35(11), pp. 1621–1631. doi: 10.1108/JBIM-05-2018-0170.

- Hultink, E. J. et al. (2011) ‘Market information processing in new product development: The importance of process interdependency and data quality’, IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 58(2), pp. 199–211. doi: 10.1109/TEM.2009.2034254.

- Im, S., Montoya, M. M. and Workman, J. P. (2013) ‘Antecedents and consequences of creativity in product innovation teams’, Journal of Product Innovation Management, 30(1), pp. 170–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5885.2012.00887.x.

- Im, S. and Workman, J. P. (2004) ‘Market orientation, creativity, and new product performance in high-technology firms’, Journal of Marketing, 68(April), pp. 114–132. doi: 10.1509/jmkg.68.2.114.27788.

- Isaksen, S. G. and Ekvall, G. (2010) ‘Managing for innovation: The two faces of tension in creative climates’, Creativity and Innovation Management, 19(2), pp. 73–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8691.2010.00558.x.

- Jaworski, B. J. and Kohli, A. K. (1993) ‘Market Orientation : Antecedents and Consequences’, Journal of Marketing, 57(July), pp. 53–70.

- Kim, N., Im, S. and Slater, S. F. (2013) ‘Impact of knowledge type and strategic orientation on new product creativity and advantage in high-technology firms’, Journal of Product Innovation Management, 30(1), pp. 136–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5885.2012.00992.x.

- Kirmani, A. and Rao, A. R. (2000) ‘No pain, no gain: A critical review of the literature on signaling unobservable product quality’, Journal of Marketing, 64(2), pp. 66–79. doi: 10.1509/jmkg.64.2.66.18000.

- Kotler, P. and Keller, K. E. (2016) Marketing Management. 15th edn. Boston: Pearson Education.

- MacCormack, A. and Verganti, R. (2003) ‘Managing the sources of uncertainty: Matching process and context in software development’, Journal of Product Innovation Management, 20(3), pp. 217–232. doi: 10.1111/1540-5885.2003004.

- Malhotra, N. K., Schaller, T. K. and Patil, A. (2017) ‘Common method variance in advertising research: When to be concerned and how to control for it’, Journal of Advertising, 46(1), pp. 193–212. doi: 10.1080/00913367.2016.1252287.

- Meade, A. W., Johnson, E. C. and Braddy, P. W. (2008) ‘Power and sensitivity of alternative fit indices in tests of measurement invariance’, Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(3), pp. 568–592. doi: doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.3.568.

- Montoya-Weiss, M. M. and Calantone, R. (1994) ‘Determinants of new product performance: A review and meta-analysis’, Journal of Product Innovation Management, 11(November), pp. 397–417.

- Muthén, B. O., Muthén, L. and Asparouhov, T. (2016) Regression and mediation analysis using Mplus. Los Angeles: Muthen & Muthen.

- Nakata, C. et al. (2018) ‘New product creativity antecedents and consequences: Evidence from South Korea, Japan, and China’, Journal of Product Innovation Management, 35(6), pp. 939–959. doi: 10.1111/jpim.12436.

- Park J. S. and Suzuki, S. (2021) ‘Product creativity as an identity issue: Through the eyes of new product development team members’, Frontiers in Psychology, 12(July). doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.646766.

- Parry, M. E. and Song, M. (2010) ‘Market information acquisition, use, and new venture performance’, Journal of Product Innovation Management, 27(7), pp. 1112–1126. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5885.2010.00774.x.

- Paulus, P. B. (2002) ‘Different ponds for different fish: A contrasting perspective on team innovation’, Applied Psychology, 51(3), pp. 394–399. doi: 10.1111/1464-0597.00973.

- Peteraf, M. (1993) ‘The cornerstones of competitive advantage: A resource-based view’, Strategic Management Journal, 14, pp. 179–191. doi: 10.1002/smj.4250140303.

- Peteraf, M. and Barney, J. (2003) ‘Unraveling the resource based tangle’, Manegerial and Decision Economics, 24, pp. 309-323.

- Selmi, N. and Chaney, D. (2018) ‘A measure of revenue management orientation and its mediating role in the relationship between market orientation and performance’, Journal of Business Research. Elsevier, 89(April), pp. 99–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.04.008.

- Song, M. and Montoya-Weiss, M. M. (2001) ‘The effect of perceived technological uncertainty on Japanese new product development’, Academy of Management Journal, 44(1), pp. 61–80. doi: 10.2307/3069337.

- Spence, M. (1973) ‘Job market signaling’, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 30(3), pp. 355–374.

- Stein, M. I. (1953) ‘Creativity and culture’, Journal of Psychology, 36(2), pp. 311–322.

- Stewart, D. W. and Zinkhan, G. M. (2006) ‘Enhancing marketing theory in academic research’, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 34(4), pp. 477–480. doi: 10.1177/0092070306291975.

- Stock, R. M. and Zacharias, N. A. (2013) ‘Two sides of the same coin: How do different dimensions of product program innovativeness affect customer Loyalty?’, Journal of Product Innovation Management, 30(3), pp. 516–532. doi: 10.1111/jpim.12006.

- Szymanski, D. M., Kroff, M. W. and Troy, L. C. (2007) ‘Innovativeness and new product success: Insights from the cumulative evidence’, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 35(1), pp. 35–52. doi: 10.1007/s11747-006-0014-0.

- Vandenberg, R. and Lance, C. (2000) ‘A review and synthesis of the measurement invariance literature: Suggestions, practices, and recommendations for organizational research’, Organizational Research Methods, 3(1), pp. 4–70. Available at: http://orm.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/3/1/4.

- Wall, T. D. et al. (2004) ‘On the validity of subjective measures of company performance’, Personnel Psychology, 57, pp. 95–118. doi: 10.1159/000172511.

- West, S. G., Taylor, A. B. and Wu, W. (2012) ‘Model fit and model selection in structural equation modeling’, in Hoyle, R. (ed.) Handbook of structural equation modeling. New York: The Guilford Press, pp. 209–231.

- Xu, B. (2020) ‘A competitive resource: consumer-perceived new-product creativity’, Journal of Product and Brand Management, 29(7), pp. 999–1010. doi: 10.1108/JPBM-10-2018-2075.

- Yi, H. T., Amenuvor, F. E. and Boateng, H. (2021) ‘The impact of entrepreneurial orientation on new product creativity, competitive advantage and new product performance in smes: The moderating role of corporate life cycle’, Sustainability (Switzerland), 13(6). doi: 10.3390/su13063586.

- Zuo, L., Fisher, G. J. and Yang, Z. (2019) ‘Organizational learning and technological innovation: the distinct dimensions of novelty and meaningfulness that impact firm performance’, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 47(6), pp. 1166–1183. doi: 10.1007/s11747-019-00633-1.