Introduction

The fact that the Internet’s potential is not to be underestimated has been clear for more than two decades. However, only the recent years have truly shown the diversity of activities that the Internet can perform and the vast areas that it can be applied to. Both businesses and consumers have started to heavily rely on the Internet as a way of conducting day to day business and completing transactions.

The online retailing has partly lost its novelty aspect and every day more and more consumers are becoming familiar with the online purchase process. However retailers are still facing questions such as why are certain products being predominantly sold online and not offline? Are there certain characteristics which make these products more suitable for online selling? How can a company explore in advance just how successful a certain product will be on the internet platform? Several studies have investigated what factors strongly impact the product suitability to be sold online (Kiang et al. 2000; Phau and Poon 2000; Peterson et al. 1997; Bhatnagar et al. 2000; Granados et al. 2007; Girard et al. 2002). But in order to be able to predict the success of (specific) products in particular, the retailers need to know what factors are influencing and ways to influence them by adapting either the marketing strategy as a whole or specific elements in the marketing mix.

Several research companies such as Nielsen have been running every year reports investigating what the most sold online products are. The purpose of this study is to try and prove empirically that there is an explanation behind this popularity, namely that it can be explained by a range of factors, the educational level being one of them.

Literature Review

Over the years the researchers have drawn attention to the necessity of categorizing products. This study uses the term “product classification” in a different way than the usual online store would, by classifying products as belonging to “sports equipment”, “electronic equipment”, “household goods”, or “music and DJ equipment”. It uses the concept of product classification that has been the subject of many studies trying to create and develop a standard high level categorization mechanism that both retailers and consumers could use, independent of the industry, product manufactures, country sold it or web shopping savviness.

A comprehensive literature review (Varvara Mityko 2011) revealed that there are 22 different models of categorization from 52 researchers. The rationale behind the multitude of models is that they have different units of analysis, the research hypotheses differ and the classification dimension perspectives are varied. The SEC model is one of these 22, and the origins lie in Nelson’s research. According to his study (1970), products could either be search or experience. Darby and Karni (1973) extended it, followed by Klein in 1998 and the result was a model which distinguished between search, experience 1, experience 2 and credence products.

According to this classification scheme products are being categorized by the degree of evaluation of a product’s quality prior or after purchase. Search products are those whose quality can be objectively evaluated by the consumer prior to purchase and therefore there are certain factors which play a role in the purchase decision. Experience goods have to be tried out before purchase either in the traditional store or in the electronic environment. Only after testing can a consumer form an opinion about the product’s quality and benefits. While the limitations to each product type have been clearly defined by Nelson, Klein has investigated whether products can shift from one product type to another, an experience good having the potential of becoming a search good should certain conditions be met. And finally, credence products are those whose qualities and benefits the consumers might not perceive even after purchasing them and have to rely on word of mouth, recommendations or brand reputation as a sign of quality.

Although the list of models can go on, the purpose of this study is to use the SEC model in investigating the hypothesis mentioned in the next chapter, this is why the literature review does not go further at this point.

Conceptual Framework and Hypothesis Development

As mentioned earlier, the goods were classified according to Nelson’s (1970) classification model – which was extended by Darby and Karni (1973) and Klein (1998) – as search, experience or credence, depending on whether the consumer can evaluate the products’ quality and their benefits before or after purchase. And it is this consumer evaluation that plays an important role to which category a product belongs to, as this perception can be influenced by several factors such as: education level, country or origin, culture, gender, age, frequency of shopping on the internet, previous experience with the online platform, etc. Some consumers with a higher degree of web experience feel that the internet does not pose any major risk regarding security and feel quite comfortable in purchasing almost daily for products ranging from holiday tickets to vacations, groceries and presents. Other consumers from certain cultures believe in testing the product first or rely more than other consumers on the word of mouth, recommendations from friends or brand reputation.

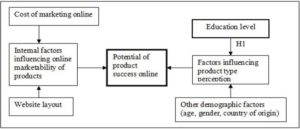

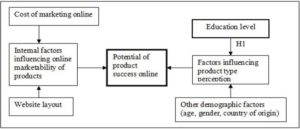

Figure 1 illustrates the research framework and conceptualization of the relationship between potential of product success online and affective factors.

Figure 1: Research Framework

The developed hypothesis is the following:

H10: There is no significant correlation between the education level and product perception as search, experience or credence.

H11: There is a significant correlation between the education level and product perception as search, experience or credence.

Both hypotheses have been tested for each of the 10 products, namely: airline tickets, groceries, clothes, books, mp3 and music download, body lotion and face care products, flowers, perfume, laptops and vitamins.

Methodology

Procedure

Data has been gathered through a structured semi open questionnaire. The questionnaires were e-mailed with a cover letter thanking the potential respondent for their participation and with a link to the online survey website. In total this study received 271 valid completed responses. Data were collected during the autumn of 2011.

Questionnaire Design

The instrument used for data collection for this study is a self-administered questionnaire. The questionnaire is divided into three parts which address issues such as online shopping experience, frequency of shopping online, reasons for shopping online or not, website design, trust and trustworthiness, product, and demographic respectively.Two sections are relevant for this paper. The questionnaire was comprised of 46 questions out of which 12 questions directly related to the SEC classification model.

The structured questionnaire was used to collect the necessary data which served as primary data to investigate whether the hypotheses enounced in the previous chapter can be accepted or not.

Respondents Demographic Profile

Of the respondents 34% were female and 66% were male. More than half of the respondents (57%) are between the ages of 20 to 25; 9.6% between the ages of 26 to 30; 5% ages 31 to 35; 13% between 36 and 40; 6.6% between 41 and 45 and 8.5% of the respondents older than 41.

Figure 2: Age Group and Education Level Distribution

Figure 2 shows the age distribution and education level — measured in the highest degree obtained at the moment of data collection — of the respondents. Around 55% of the respondents have listed as having already obtained a high school degree, 21% were holding an undergraduate degree and approximately 26 percent had a graduate or higher degree. The respondents were also asked whether they were familiar with the possibility of shopping online, question which has been answered positively by 99%.

Results and Statistical Analysis

Data Analysis

The various statistical techniques that are used in the data analysis are described in this section. Frequency Distribution Analysis is used to determine a demographic profile of the survey respondents. Cross-tab and Pearson Chi-square Test are used to determine the relationship between age, gender and product types according to the SEC classification. For the test of independence – test of homogeneity – the chi-squared probability of less than or equal to 0.05 has been chosen.

Hypotheses Testing

The main aim of this part of the study is to test the hypotheses that were developed earlier, namely if there is a correlation between age and gender and the perception of product classification as being search, experience or credence.

Based on the results, there is empirical support for the above mentioned hypothesis. With regard to education, the null hypothesis can be accepted for 7 out of the 10 investigated products. The alternative hypothesis, meaning a significant correlation, is valid for airline tickets, groceries, and vitamins. If we look at how the respondents classified these 3 products, we notice that there is a significant correlation between the education level and search and experience type of products. The relationship between age and these products is that the older a person is, the more he/she perceives the product as being rather experience or credence than search.

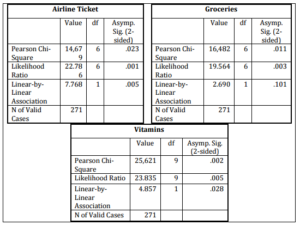

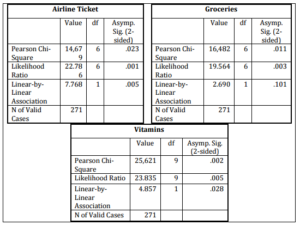

Figure 3 shows the results for the testing of H10, for those products where this hypothesis can be rejected.

Figure 3: Pearson Chi Square Values for Selected Products

Figure 4 presents the results of testing the hypothesis H10, for the rest of the products where the hypothesis holds true, namely that there is no significant correlation between the education level and product perception as search, experience or credence.

Figure 4: Pearson Chi Square Values for the Remaining Products

Discussion and Implications

There are several important implications from this research.

First, the study finds that education plays a role in how consumers perceive the products, which could be indirectly related to the web experience they have; the less they feel uncertain about product attributes, benefits and quality. This indicates that the SEC paradigm, although used in many other studies as a starting point for classifying products, may prove to be rather subjective, depending on the customer perception, which in return depends on factors such as age or gender, or education level. Retailers have been gathering information about consumers’ purchases so that they can tailor their offering to the consumers’ preferences. This entails that the retailers have to incorporate the “education” factor in the data gathering process as well and cross reference it with the products they would normally recommend.

Second, if education is impacting the way the consumers perceive a product in the case of online shopping, it is clear that more products than the ones surveyed in this study will be impacted. Moreover, while education has proven not to have a significant influence on certain products in the tested set, it can be stated that education influences directly other factors, such as income, which in return impacts the product perception.

Third, education could impact indirectly the product perception by playing a role in the factor of web experience or frequency of online purchase. The online shopping differs from the traditional transaction in the physical store in that it requires a set of skills, and is not simply a usage of a credit or debit card. The consumer needs to know where to look for information about the product, where to buy and how.

Conclusions

This study adds to those already reported in the literature in several ways. First, it uses an international, rather than regional or national sample of online consumers. Second the questionnaire was developed to use actual online shopping behaviour rather than hypothetical scenarios. This research explored the difference that the education factor possesses in the perception of selected products from the SEC classification model. The study found that in some cases and for some specific products the degree of the online consumer has an influence on his/her perception of product qualities and therefore their category. If the SEC paradigm is to be used objectively for classifying products both offline and online, tests for a different influencing factor such as frequency of shopping, or other demographic characteristics (age, gender, income, culture or country of origin/residence) could also be run to make sure the variables are known and can be controlled.

References

Bhatnagar, A. Misra, S. & Rao, H. R. (2000). “On Risk, Convenience and Internet Shopping Behaviour,”Communications of the ACM, 43 (11), 98-105.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Darby, M. R. & Karni, E. (1973). “Free Competition and the Optimal Amount of Fraud,” Journal of Law and Economics,16, 67-88.

Publisher – Google Scholar

De Figueiredo, J. M. (2000). “Finding Sustainable Profitability in Electronic Commerce,” Sloan Management Review, Summer, 41-52.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Girard, T., Silverblatt, R. & Korgaonkar, P. (2002). “Influence of Product Class on Preference for Shopping on the Internet,” [Online]. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, Volume 8 (1). [02.03.2012,] Available:http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/cgi-bin/fulltext/120837863/HTMLSTART

Publisher

Granados, N. F., Gupta, A. & Kauffman, R. J. (2007). “IT-Enabled Transparent Electronic Markets: The Case of the Air Travel Industry,” Information Systems and E-Business Management, 5 (1), 65-91.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Kiang, M. Y., Raghu, T. S. & Shang, K. H.- M. (2000). “Marketing on the Internet – Who Can Benefit from an Online Marketing Approach,” Decision Support Systems, 27, 383-393.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Kiang, M. Y., Ye, Q., Hao, Y., Chen, M. & Li, Y. (2011). “A Service-Oriented Analysis of Online Product Classification Methods,” Decision Support Systems, 52, 28-39.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Klein, L. R. (1998). “Evaluating the Potential of Interactive Media through a New Lens: Search Versus Experience Goods,” Journal of Business Research, 41, 195-203.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Nelson, P. (1970). “Information and Consumer Behaviour,” Journal of Political Economy, 78 (2), 311-329.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Peterson, R. A., Balasubramanian, S. & Bronnenber, B. J. (1997). “Exploring the Implications of the Internet for Consumer Marketing,” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 25 (4), 329-346.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Phau, I. & Poon, S. M. (2000). “Factors Influencing the Types of Products and Services Purchased Over the Internet,”Internet Research: Electronic Networking Applications and Policy, 10 (2), 102-113.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Varvara Mityko, S. (2011). ‘Product Categorization in the E-Commerce Environment,’ Proceedings of the 5th International Conference Globalization and Higher Education in Economics and Business Administration (GEBA), ISBN 978-973-703-697-1, 20-22 October 2011, Iasi, Romania, 1-12.