Introduction

Trust and Mistrust in E-commerce

The evolution of the Internet has taken it from a tool used solely for research by researchers to a market force in the consumer network, offering goods and services outside of the consumer’s physical locality and time zone. The comfort of the home offers consumers the opportunity to research, compare and contrast business offerings with minimal time and financial outlay. Businesses are given the opportunity to reach an audience limited only by accessibility to the Internet. However, in all business ventures, there is always risk involved and the Web environment is no exception.

The notion of trust is especially relevant in the online context where the intended purchase may be from a supplier that is operating in a different country, time zone, currency and legal system, rendering data vulnerable to security breaches and misuse. B2C e-commerce has its own exclusive set of risks not experienced by the Bricks and Mortar (B&M) shop front business (Gefen and Straub, 2004, Ba, 2001, Furger, 1998, Pavlou and Mendel., 2006), due to the removal of the human aspect of verification and immediacy of purchase to a virtual and dehumanized interaction.

The development of trust in B2C Internet e-commerce received substantial attention in the first part of the decade, without due recognition to the continuing status of to the early adopters, who were slipping away due to concerns and experiences of fraudulent activity or poor service. Three pertinent surveys undertaken by the International Crime Victimisation Survey’s (ICVS) Australian component into the prevalence, reporting and handling of Internet crime as perceived by households, conducted by the Australian Institute of Crime (Krone and Johnson, 2007 ) and the U.S.A Internet Computer Crime Report (ITCC, 2007) found that there is an increase in problematic behaviour, concerns with security and a growing lack of confidence in Internet commerce in Australia and the U.S.A. The issues facing B2C Internet e-commerce over the coming years must therefore relate more to minimise perceived risk to consumers in a bid to hold onto their trust once the initial trust has been achieved if B2C Internet e-commerce is to continue to thrive.

It must not be underestimated how difficult it is for SMEs to build the initial trust of consumers given their inability to compete with larger enterprises with greater resources availalbe to ensure secure infrastructure, reputation, presence and trust.

To assist SMEs to build initial trust, previous studies (Farrell, 2004, Farrell et al., 2003) have attempted to collate trust factors identified by rigorous research from contributing disciplines to give an overview of risk and trust determination factors for the development of B2C e-commerce. Alternative methods of gaining trust were identified (Farrell and Scheepers, 2008) for SMEs and found to be successful. Guidelines have been developed by the OECD to assist in the creation of an e-commerce application that minimised the risks to consumers (OECD, 1999). These have also been modified to suit Australian business in the Australian e-commerce “Best Practice Model for Business” (Department of Treasury, May 2000). While the guidelines may offer the most scientific or technical solutions to risk with e-commerce, trust is not the inevitable outcome. The sociological consideration to the perception and acceptance of risk is summarised by Short (Short, 1984 ) who states that “response to hazards is mediated by social influences transmitted by friends, family, fellow workers and respected public officials” illustrating that there are other influences on perceived risk outside the realm of the e-commerce developer. Slovic (Slovic, 1987) argues, “disagreements about risk should not be expected to evaporate in the presence of evidence”. It is feasible however to use the research and guidelines to initiate an environment that embraces procedures to reduce risk and consequentially increase the development of the consumer’s initial trust.

To maintain trust for the long term, trust must be fed and exercised. While these models set up for best practices in developing e-commerce there is a need to be ever vigilant and recognise what is happening in this vulnerable industry. To gain trust is a slow and steady process that is not to be taken lightly. To achieve ongoing trust, the risks and challenges facing the e-commerce business must be identified and consideration must be given to how to make it a safe and secure environment for customers.

This paper questions “What can be learned from a study of successful B2C e-commerce SMEs in relation to maintaing trust after the initial development?”. It will consider the experiences of six online SMEs to improve the understanding of the interactions of information technology related innovations and organisational contexts (Cavaye, 1995). The paper will explore SMEs that have developed start-up Internet based e-commerce businesses in Australia and the methods they have engaged to keep trust and loyalty of engaged clients. Finally it will propose a set of guidelines to assist in reducing security issues and business risks in order to encourage ongoing consumer trust, thereby reducing the opportunity for mistrust.

Working Definition of Trust

E-commerce is a multi-disciplinary area of research, each discipline offering its own view of trust. E-commerce trust may relate to the trust of a social and judicial structure to ensure the security of purchases, economic trust that equates potential risk with potential gain, technical risk with unknown technology and/or psychological risk with the individual behind the e-commerce business. McKnight et al (McKnight et al., 2001) concede that “there is no agreed upon definition of trust due to different definitions coming out of varying disciplines”. Regardless of the context, discipline or the trust beliefs of the consumer, most researchers agree that trust in an e-commerce, B2C relationship, is related to risk, or more precisely, inversely related to risk. Trust also involves the consumer’s willingness to be involved in a risk-taking situation where it is necessary to calculate the benefits and possible losses subjectively when not all the negative outcomes are known. Trust in B2C e-commerce is dynamic and continually reassessed as more information becomes apparent. It is from this perspective that this research will consider trust in a B2C, Internet based, e-commerce relationship.

Developing Trust and Distrust

While most risks can be overcome by adhering to technical solutions, human computer interaction guidelines, sound business and social practices, the consumer must trust the company and its ability to provide a solid, secure business by demonstrating both best practices and a benevolent behaviour.

Previous research (Farrell et al., 2003, Farrell, 2004) recognized identifiable risks and perceived risks with the company and the company’s ability. The studies have led to a set of factors to be considered when developing an e-commerce B2C application that will help to reduce the risks and consequently increase trust. This research has been developed from academic studies from varying disciplines. It collates risk and trust factors that assist in the establishment of a B2C e-commerce business that adopts methods and procedures to assist in the formation of a trusting, safe and secure environment.

Much of the previous research tends to stop at this point where establishment of trust is developed and processes are in place to ensure a safe and secure environment. This is exemplified in the research as mentioned in the introduction of this paper, the OECD (OECD, 1999) guidelines and subsequently the Australian e-commerce Best Practice Model for Business E-commerce (Department of Treasury, May 2000). E-commerce belongs to a world that is constantly changing at an exponential rate, hence to be involved in e-commerce, it is essential to continue being ever vigilant and up to date with the latest risks.

To develop trust in consumers, previous studies (Farrell and Scheepers, 2008) encouraged the inclusion of community and benevolence. Studies undertaken by Gefen and Straub (Gefen and Straub, 2004) demonstrate the importance of social presence to build trust through the perception that the vendor is displaying through the Website a sense of personal, sociable, and sensitive human contact. They assert that these features of human contact and benevolence are expected from companies providing services and products. Trust will follow when a trusted party acts in accordance with the expectations of the trustee. In e-commerce, where social presence is at a minimum, it becomes even more apparent when expected norms are not forthcoming. McKnight views the need for Web vendors to try to gain a competitive advantage by understanding the individual consumers better, just as face-to-face salespeople try to get to know the potential customer so they can relate to them better (McKnight and Chervany, 2001b).

It may not be the decision of the e-commerce company to disregard the expectations of the consumer, rather an external influence that changes the course of the regular actions, resulting in an unexpected and possible unwanted outcome. This unexpected outcome may lead to tipping the balance in what is an already fragile relationship of trust, leading to distrust. Robinson (Robinson, 1996) claims that distrust usually arises for good reason. Most people are trusting until the other party proves untrustworthy. Without the personal intervention that is available to most other forms of communication and transactions, the ability to monitor and explain the situation is drastically reduced. Therefore, the negative emotional reaction as described by Robinson, that is resultant from a breach of trust, would be unanswered and be strongly associated with distrust.

Distrust although generally considered to be a negative power in a purchasing relationship should not be considered entirely as such in e-commerce. (Cofta, 2006) describes entering into an e-commerce transaction without distrust as “entering without vigilance and prudence”. This behaviour of acting without distrust was demonstrated in previous study (Farrell and Scheepers, 2008) where participants indicated their intention to embark on purchases in a “blind trust” where vigilance and prudence would have been a safer alternative. However Cofta also maintains that a continuity of trust supports the perception that the ‘order of the world’ will remain stable so that no undesired discontinuity will get into the way of the “trustee acting for our benefit”. When an intrusion into the order ensues, distrust is able to manifest itself into the minds of the consumer. This distrust may lead to what McKnight et al. describe as distrusting intention where “one is not willing to depend, or intends not to depend, on the other party, with a feeling of relative certainty or confidence” (McKnight and Chervany, 2001a).

(Lewicki and Tomlinson, 2003) define distrust as the motives, intentions and behaviours as sinister and harmful to the others interest and that distrust will increase with the magnitude, frequency and intention of the violation. They further suggest that efforts to restore the relationship are met with “skepticism and suspicion” resulting in a “self-fulfilling prophecy” of justifying their decision to distrust. Cofta (2006) asserts that a lack of trust may make the decision to purchase more difficult while distrust “irrevocably excludes services from being selected at all, low trust can be repaired, distrust is the end of a service”.

A breach in expected behaviour leaves the vendor to deal with the loss of trust or the building of distrust. McKnight and Choudhury compare dispositional distrust to dispositional trust and assert that the distrust concepts are better predictors of risky concepts and intentions to use the site (McKnight and Choudhury, 2006).

In the evidence of previous research into distrust in e-commerce it is apparent that distrust, while being essential to initial trusting determination, requires strict attention to ensure it is not given an opportunity to rise in the minds of the consumer once trust has been attained. It is essential for the SMEs that strategies and vigilance are employed to ensure that events leading to distrust do not occur.

The following section considers companies that have survived as online B2C SMEs and have developed methods and strategies to deal with unexpected, though persistent, threats to how they are perceived. Due to its size and the costs involved in 24/7 vigilance, the SME finds itself at a disadvantage to larger businesses that are able to ensure the continuing security of its business. Each of the companies has worked through the stage of building trust in order to encourage customers to their online stores. Their experiences will be discussed and guidelines presented to assist with long term maintenance of trust in B2C e-commerce for SMEs.

The B2C E-commerce SMEs

As devastating as it was, the “dot-com crash of 2002” produced a host of survivors with strong business plans and an astute eye on what was happening in the industry. In adhering to their conventional strategies they may not have experienced the boom that many volatile dot-com businesses enjoyed, but traded it for a slow steady growth phase, giving them time to evaluate and learn from their own and other’s online business experiences. In Australia, the post dot-com e-commerce survivors are now able to benefit from a substantial steady growth.

The companies discussed here have all survived the dot-com crash and have maintained customer loyalty and trust over the subsequent years. Initial trust was encouraged by the companies by behaving as expected by the consumers, demonstrating benevolence, social presence, community building and recognising customer loyalty. The sustaining of consumer trust for these SMEs has not been simply a case of ‘resting on their laurels’ once the initial trust has been established, rather constant vigilance and continually keeping on track of current practices or mis-practices by unscrupulous external influences.

The focus of the discussion in this paper is the perspective of management and the viewing of other evidence such as web sites, company policies and strategic directions. In all, 9 companies were initially contacted in 2006, 6 of which were followed up with semi-structured interviews in accordance with guidelines (Neuman, 2006). Discussions were held with the CEOs, owners and managers of each of the businesses described below (2.1). Interviews were underaken with managers who were all involved wtih the decision making process of the companies online strategies and the implementation of these strategies. The information gathered from the intervews were experiential and in most parts qualitative. A variety of Information Systems data gathering techniques were used as recommended by Darke (Darke et al., 1989) including an initial open-ended discussion with the owner, a visit to the offices and further discussions on issues raised during the initial contact, e-mail exchanges and inspection of the Websites. To assess internal validity (Yin, 1989, Yin, 2003), there were email follow-ups to ensure the accuracy of the information that was being delivered.

The products for sale in these stores were not large value items thereby not enabling a substantial risk on a normal size order that would require further checking. This assists when comparing stores in the nature of their business and the relative risk of fraud or deception. The names to be used are BookCo, ParentCo, GardenCo, as FlowerCo, HealthCo and ComputerCo (all pseudonyms) for the companies.

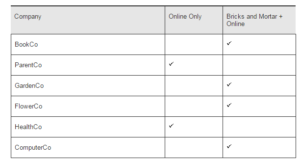

The selection for the study in this chapter followed the criterion of an association of some type of special interest community, and that their online business strategy was tied with product/service provision to this community. These attributes being the positive factors which were most commented on by the participants of the previous studies (Farrell et al., 2003, Farrell, 2006, Farrell, 2004). Other criteria included awareness by each organisation of issues pertaining to trust engendering factors (Farrell et al., 2003) and community loyalty. Each company also meet the criterion for literal comparison (Yin, 2003), as they were all small businesses of less than 30 employees and were successfully trading online for at least 2 years. The research design accommodates for various business models (i.e., ‘Bricks and Mortar’ online only and B&M combined with an online presence (Table 1).

Table 1: Presence of Company

Profiles

BookCo was established as a Bricks and Mortar (B&M) company and has grown to 5 outlets within Victoria over the past 20 years, extending their sales to online in 2002. BookCo is well renowned for its benevolent in-store behaviour offering community information, arranging guest speakers, book clubs and social functions. BookCo had a strong alliance of customers before moving to online sales.

ParentCo was established in Melbourne in 1999 as an e-commerce B2C business that is solely online, selling products relating to newborns, young children and mothers. ParentCo provides a place for parents to receive advice, information and to meet other parents online. ParentCo has a business strategy that encourages a strong membership involvement of over 90,000 members in discussion boards, online information and a shopping mall. The membership is not only Australia wide but world wide, creating a 24 hour involvement in its many features. The continual 24/7 basis creates a dynamic environment that offers constant new information and discussions to housebound parents. It boasts sponsorship from large multinational companies that are household names and family oriented, that in return receive the benefit of linkage from the substantial membership. Today the business generates approximately 40% of its total sales via the ParentCo Web site the remainder being through eBay sales.

GardenCo was established in 1978 as a shop front and mail order business selling plant and seeds. GardenCo offers club membership giving discounts to members. Online purchasing was introduced in 2002 and has built its online orders to 30% of total business of which 90% are club members. Mail orders have reduced 40% over this time. GardenCo has a strong supportive membership that involves activities and advice as well as discount purchases from their store.

ComputerCo was established in Melbourne CBD specialising in handheld devices, PDAs, Mobiles, GPS Solutions, Notebooks and wireless technologies. It was initially established as a B&M store and extended its business to online in 1998. It is not obvious on entering ComputerCo that it also runs as an online business. The online department runs from the upstairs offices within the same building, from here staff have instant access to available stock. The online store generates approximately 20% of overall sales.

FlowerCo is a second generation long term established family business in Melbourne inner suburbs. The online store was established in 2000 and accounts for approximately 10% of sales. FlowerCo sells and delivers flowers and floral arrangements, catering for general requests or specific occasions such as weddings and mother’s day.

HealthCo established in 2000, has a B&M store front in Melbourne. The shop front is not in a shopping centre but rather a warehousing area. Customers are able to visit the site however this is a rare event. The online store offers equipment to assist with back disorders, offers medical advice, story sharing and discussion forums. HealthCo is for all intents and purposes an online store with 100% of trade online. Discussion forums are member based. HealthCo permits other methods of payment after ordering online such as fax, phone and cheque. HealthCo has increased its online payment acceptance from 80% online, 10% fax, 9% phone and 1% cheque to 92-94% online, 4-5% phone, <1% fax , and <1% cheque in the 6 month period previous to the interview.

Safeguarding Trust

The companies discussed were developed to create a personal, trusting environment where members are individuals, navigation is easy and technical solutions now exist. While this creates an environment that is as risk free as possible, experience has found that risk avoidance is an ongoing process. The following sections are the discussions held with the CEOs about their experiences and their recommendations to overcome these risks. The guidelines are sumarised in Section 3.

Ensuring the Site is Stable and Usable

Risks with Employing Professionals in Site Development

HealthCo experienced an unsuccessful first release of their online business due to an incompetent, overpriced developer who did not have an understanding of the marketplace. While they were able to develop a relationship with their customers initially, constant server breakdowns gave way to distrust in their ability to meet the requirements of a secure, safe site.

HealthCo now recommend the following when selecting a Web developer:

“The Internet has its own language specific to computers and the WWW. New users to e-commerce need to be brought in gradually in a language they can understand. Hence it is essential to select a developer with good communication and not jargon speakers, who will test your site with real users.

Price was not a reflection of the service that was provided, reasonably priced developers are as likely to provide a good service as those who are extremely overpriced. One method of finding the right developer is to find Web sites that you feel express the image you want to present and approach the developer. Only being able to code a Web site is not sufficient, a working knowledge of marketing and search engine optimisation, are also essential components of the e-commerce developers abilities. This may require the employment of an e-commerce team.”

Risks with Employing Professionals with Server Storage

Initially, FlowerCo selected a host for their site assuming “they would all offer basically the same services”. This was not the case after daily problems being reported by customers. The host proportioned the blame on the software that was used on the site. While FlowerCo were in a position to move their B&M customers to online customers in the early stages with a transferral of trust, they subsequently lost a substantial number of orders from customers who did not feel they had met with a standard of reliable service.

Counter Action

A reliable host was selected supplying a 24/7 reply with mobile access for emergencies. This host could demonstrate the reliability of their service through logs and client recommendations. This service has not failed in the 2 years it has been active.

FlowerCo felt that their haste in employing a server provider created a serious problem for the initial users moving to online purchasing. They advocate now that by not recognising the importance of the partnership with the host company, they had damaged their move online and that research into a well reputed host provider is essential before startup.

Guideline 1: Develop a stable, professional site by spending time selecting the right people to build your business

Watch Your Discussion Board for Security Issues or Undesirables

Risk with Privacy and Security: It was reported on a discussion board that ParentCo gave out personal details to list brokers. The reaction from members was quite vocal as they felt they had been betrayed. In fact, list brokers who requested information to be sent out to the members, did so through ParentCo who themselves, forwarded the information to the members only when they thought it could be of benefit to the members. No personal data was ever sold or given to another organisation. This misrepresentation and subsequent backlash was caused by the list broker who did not differentiate between those who sold them data and those who allowed for information to reach their clients without passing out personal details. Secondly, by the member who went straight to the discussion board without checking with ParentCo.

Risk with Undesirables:

The Competition: Again using the threat of personal information given out, a “new” member placed on the discussion board a message regarding having received a call from a company claiming they had obtained their personal information from ParentCo. When traced, it was found that the discussion board message came from the Internet protocol address (IP address) of a competitor.

Prowlers: ParentCo has been established for the benefit of parents, in the main the clients are mothers. At times infiltration can occur where a person with wrong intentions can assume the persona of a typical ParentCo member in order to gain the access to and trust of other members.

Spin offs: A member who was offered a free month of a discussion board, advertised on ParentCo for others to come join their new site. This did attract a small number of members to the new site from ParentCo. While this may be considered as a concern of loss of business this is not the major concern. Given that it is seen as a spin off from ParentCo, unethical or insecure behaviour on the spin off could reflect on ParentCo. This was the case given that the IP offering the free discussion board was an overseas company in Russia that did not identify itself. This allowed the IP to collect information in regards to each of the users attached to this discussion board.

Behavioural Vulnerabilities: According to the CEO of ParentCo, given the nature of many of the members, it is not unusual for behavioural problems caused by sleep deprivation, variable hormones and stress creating volatile discussions that require intermediary intervention. HealthCo also found that they need to keep an eye on unsavory behaviour by participants in the discussion room.

Counter Action

ParentCo and HealthCo encourage their long serving members to keep an eye on the discussion board, watching for any derogatory comments or suspicious behaviour. Given the large number of members and the demographics, it is possible to cover a 24/7 watch on the conversations that are occurring. These members are known as moderators. The intervention of a moderator shows that there is a constant vigilance on the site which increases trust in the company’s ability to protect the members as individuals. ParentCo has future plans to include reward points towards purchases for monitoring of the discussion board.

HealthCo also has a language checker running in the background to reduce offensive behaviour.

Guideline 2: Keep a watch on your companies discussion boards 24/7

Guideline 2.1: Watch for any disturbances to satisfaction with the business, security, trust and privacy

Guideline 2.2: Watch for infiltration by undesirables

Pre-empting Security Issues

Risks with Hackers

Hackers: From the beginning, hackers have been at the doors, often just to be a nuisance or to test their skills as a hacker. More recently this has turned into a lucrative area for identity and credit card theft. 24/7 vigilance is essential to ensure a secure site and that the site is not taken down, script injection or denial of service does not occur.

ParentCo used PHP-BB for their discussion board, an integral part of their business. PHP-BB is an open source high powered, fully scalable, and highly customisable bulletin board package that is used in many of the online businesses both in Australia and worldwide. Early in 2005, rumours started on the hackers sites regarding the vulnerability of PHP-BB, eventually leading to many PHP-BB sites being brought down in May 2005. This led to large financial losses and loss of trust in the company’s ability to deal with the security side of their business. ParentCo was aware of the rumours that had been circulating and migrated to VBulletin with 3 all night vigils to monitor vulnerability and for the change over to occur so that there would be no down time.

Counter Action

ParentCo trawls the hackers pages looking for new methods to hack sites and rumours that may indicate vulnerabilities of existing sites and packages. This is a continuous exercise as most software development companies react to hacks rather than keeping on top of the latest movements. ParentCo recognises the need to be ever vigilant with hackers.

Guideline 3: Keep up the security by knowing what is happening before the hacking occurs

Guideline 3.1: Trawl the hackers sites, watching for any discussions that may affect your business, regarding software vulnerabilities or security issues.

Ensure Your Server is Stable and Secure

Risks with Server

Going offshore: Keeping a Web application on one server leaves it open to the vulnerabilities of the Internet provider. It is exceptionally expensive to host a site as large and as frequently accessed as both ParentCo and HealthCo. Reducing vulnerability of a single server by hosting on multiple servers is even more financially prohibitive to Australian SMEs.

Counter Action

The financial restrictions are not relevant to the United States of America (USA) where it is possible to divide the application into 3 applications each in different areas of the USA at a cost far less than the single server Internet provider in Australia. A full copy of the application is kept on a server as backup in the home office. This reduces the vulnerability of the whole application, given that only one part would be affected at any time and can be immediately backed up and redirected at another site. However, the physical Pacific connection becomes the vulnerable component, given that many large Australian e-businesses use USA Internet providers.

Guideline 4: Reduce Server Vulnerability

Guideline 4.1: Do not rely on only one Internet Service Provider to host the site.

Guideline 4.2: Create contingency plans should a site go down

Continue to Develop New Ways to Build and Encourage Trust

Risk with not Diversifying to Encourage Trust

Although ParentCo has been trading for 6 years, customers are still wary of entering their credit card details on their site. The site has SSL and encryption. Data is securely stored. All orders are checked before delivery.

Counter Action

One of the methods of developing trust in their e-commerce side of their site is by having an eBay store. Customers can bid on products that are also available on ParentCo for purchase. eBay customers are informed of the availability of products on ParentCo. This not only brings customers but also new members to the portal, a positive business decision.

The latest initiative is to use barcoded tags in Australia Post to purchase products from ParentCo. Members who are not at first comfortable with using the ParentCo site for ordering can go to any one of over 9.000 post offices in Australia. A product tag is collected for any item they have seen on ParentCo, order and payment is made at the post office. This has provided the Internet store with an online product listing and information with the advantages of a B&M store local to the majority of Australian customers. Customers still have all the advantages of membership of ParentCo, awareness of available products and a secure purchasing that initiates their business relationship with ParentCo.

The association with Australia Post also gives credibility to the ParentCo site that extends to the ParentCo online store.

Guideline 5: Look to other ways to offer product rather than on your own Website

Guideline 5.1: Move people gently to the Website through other avenues

Ensuring a Purchase is Valid

Risks with Orders

Invalid purchases: On viewing current orders it was apparent that there were some orders that were invalid. These fell into 2 categories, firstly the nuisance orders that had nonsensical information and details, secondly, generally overseas orders, with different postal address, shipping address, billing address and billing name on the single order.

Counter Action

Every order is checked for validity. Addresses, names and credit cards are individually checked for authenticity. ParentCo and ComputerCo do not use a merchant account but rather deal with all stages of the sales on their SSL. If a merchant account were to be used, the company would be initially charged for any claims made by the card owner and given that they do not have a signed receipt they would find it difficult to reclaim any monies that have been charged. By taking control of their own sales, they are able to view all orders before fulfillment.

Guideline 6: Monitor All Orders Before Submitting For Payment And Processing

Detecting Fraudulent Behaviour

Risks of Fraud

ComputerCo sells products that are high priced and easily sold on without traceability, hence ComputerCo has had to be extremely vigilant of their online sales. Experience has shown that there are patterns of behaviour of the fraudulent customer. While this situation is the reverse of previous situations where it is the business that is vulnerable, any fraudulent behaviour with the company changes the modus operandi of the store and can therefore cause suspicion of other customers. By ensuring the company reduces the opportunities of fraudulent behaviour, they are able to offer an interface with the customers that is stable, consistent and not demonstrating the appearance of suspicion but rather benevolence.

Counter Action

From previous experience, ComputerCo and HealthCo have developed a list of behaviours they recognise as indicators for concern with potential fraud. Establishing these checks into the set procedure of the company assists in recognising concerns without having to change tactics when issues arise.

ComputerCo:

- Customer who orders and pays for goods over the phone and then comes in to collect

- Several card numbers provided to split the transaction

- Goods requested that are not normally provided by the business

- Large orders made out of the blue where no long term homework on the product or company is evident

- Pressure to pick up the goods as soon as possible particularly close to closing time

- Customers build up a reputation by starting with small honest transactions and then attempting to make a large fraudulent transaction.

HealthCo adds to this list:

- Customer who use free mail service such as yahoo

- Customers who do not include phone number

- Order in large quantities items that are generally single use and are of high value

- If the company is still concerned about the order they are entitled by the privacy laws to phone the customer personally once to validate the use of their credit card.

- HealthCo insist on the inclusion of the 3 digits for verification on the back of card although this proved to be a deterrent to genuine customers in other cases.

Guideline 7: Check list for suspicious purchaser behaviours

Guideline 7.1: Check for validity of the orders and credit card details

Guideline 7.2: Ensure there is a match between the credit card holder and the purchaser

Discussion

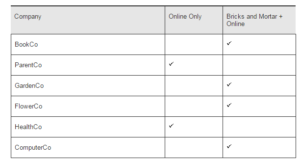

From the meetings held with each of these B2C e-commerce SMEs, it is apparent that accordance with guidelines to develop a secure and safe site is essential. However, equally important is the ongoing monitoring and maintenance of risks. It has been possible from the discussions held to derive guidelines to assist in the ongoing battle of risk reduction in B2C e-commerce. These guidelines (Table 2) establish a basis for continuance of reduced risk in a vulnerable environment. The resultant guidelines are listed in Table 2:

Table 2: Guidelines to Assist in Reducing Risk

Future start up online B2C e-commerce companies may benefit from the experience of these SMEs. Following these guidelines will help to reduce risk to the e-commerce site, and hence either increase the confidence and trust of the consumers or, at the very least, not allow for a reduction.

Summary and Conclusion

The building of consumer trust and hence reduction of risk, in a new online business has been the focus of much research in the past for B2C e-commerce. This paper has identified guidelines to assist new B2C SMEs to establish and maintain trust. The guidelines were derived from the analysis of discussions and represent the results of the experiences of companies that have either made the transition from the B&M world or have set up as online stores only. The experiences of these companies demonstrate that for business survival, constant vigilance is essential. A business that is open 24/7 must be monitored accordingly and not just responding to security breaches. Online businesses must keep up to date with what is happening not only in their own neighbourhood but also in the global neighbourhood, requiring the use of the Internet as a tool to access the thoughts and behaviours of hackers on the net. It is apparent from the ongoing experiences of the companies studied that the question of trust has not yet been answered as new technologies and threats tend to appear daily. The evolving nature of ecommerce requires that the body of knowledge of threats and risks should be constantly added to in order to extend the guidelines to assist new SMEs.

Limitations and Future Work

This paper only considers the perspective of the management of online e-commerce B2C companies and each companies implementation of trust factors that have been recognised in other studies as leading to trust in B2C e-commerce.

Future work, to fully assess the impact of the strategies employed by these companies, would require the perspective of the customers be sought and analysed.

References

BA, S. (2001). “Establishing Online Trust through a Community Responsibility System,” UMI, 31, 323-336.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Cavaye, A. L. M. (1995). “User Participation in System Development Revisited,” Information and Management, 28 311-323.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Cofta, P. (2006). ‘Distrust,’ ACM International Conference Proceeding Series; Vol. 156 archive; pages 250 – 258 Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Electronic Commerce: The New E-commerce: Innovations for Conquering Current Barriers, Obstacles and Limitations to Conducting Successful Business on the Internet Fredericton, New Brunswick, Canada ACM New York, NY, USA

Darke, P., Shanks, G. & Broadbent, M. (1989). Successfully Completing Case Study Research: Combining Rigour, Relevance and Pragmatism,” Information Systems Journal, 8, 273-289.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Department of Treasury (May 2000). ‘E-Commerce Best Practice Model for Business,’ In Consumer Affairs Division (Ed.

Farrell, V. (2004). ‘A Multidisciplinary Model of Trust in B2C Electronic Commerce,’ IFIP Working Group 8.4 Third Conference on E-business Multidisciplinary Research. Saltzburg.

Farrell, V. (2006). “Monitoring Risk and Trust Beyond the Initial Development in B2C E-commerce,” CD-ROM/Online Proceedings of the European and Mediterranean Conference on Information Systems (EMCIS) Costa Blanca, Alicante, Spain.

Publisher

Farrell, V. & Scheepers, R. (2008). “Party Trust, Control Trust and ‘Blind’ trust in Business to Consumer Electronic Commerce,” IADIS Multi Conference on Computer Science and Information Systems 2008 Amsterdam, Netherlands.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Farrell, V., Scheepers, R. & Joyce, P. (2003). “Models of Trust in Business-To-Consumer Electronic Commerce: A Review of Multi-Disciplinary Approaches,” IFIP 8-4 Working Group. Denmark, Kluwer.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Furger, R. (1998). ‘Buyer Beware,’ PC World September

Gefen, D. & Straub, D. W. (2004). “Consumer Trust in B2C e-Commerce and The Importance of Social Presence: Experiments in e-Products and e-Services,” Omega, 32, 407-424.

Publisher – Google Scholar

ITCC (2007). ‘Internet Crime Report,’ In Centre, T. N. W. C. C. (Ed. Internet Crime Complaint Centre. Bureau of Justice Assistance, Federal Bureau of Investigation.

Krone, T. & Johnson, H. (2007). “Internet Purchasing : Perceptions and Experiences of Australian Households,” Trends and Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice

Publisher – Google Scholar

Lewicki, R. J. & Tomlinson, E. C. (2003). “Distrust,” Beyond Interactability, Boulder., Conflict Research Consortium, University of Colorado,.

Publisher

Mcknight, D. H. & Chervany, N. (2001). “While Trust is Cool and Collected, Distrust is Fiery and Frenzied: A Model of Distrust Concepts,” AIS.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Mcknight, D. H. & Chervany, N. L. (2001a). “Trust and Distrust Definitions: One Bite at a Time,” Trust in Cyber-Societies: Integrating the Human and Artificial Perspectives. , 27-54.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Mcknight, D. H. & Chervany, N. L. (2001b). “What Trust Means in E-Commerce Customer Relationships: An Interdisciplinary Conceptual Typology,” International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 6, 35-37.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Mcknight, D. H. & Choudhury, V. (2006). “Distrust and Trust in B2C E-commerce: Do They Differ?,” Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Electronic Commerce:The New e-Commerce: Innovations for Conquering Current barriers, Obstacles and Limitations to Conducting Successful Business on the Internet Fredericton, New Brunswick, Canada ACM.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Neuman, W. L. (2006). Social Research Methods: Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches, 6e America Pearson.

Publisher – Google Scholar

OECD (1999). “Guidelines for Consumer Protection in the Context of Electronic Commerce,” In OECD Council (Ed).

Publisher

Pavlou, P. A. & Fygenson, M. (2006). “Understanding and Predicting Electronic Commerce Adoption: An Extension of the Theory of Planned Behaviour,” MIS Quarterly 30, 115-143.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Robinson, S. L. (1996). “Trust and Breach of the Psychological Contract,” Administrative Science Quarterly, 41, 574-599.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Short, J. F. (1984). “The Social Fabric at Risk: Toward the Social Transformation of Risk Analysis,” American Sociological Review, 49, 711- 725.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Slovic, P. (1987). “Perceptions of Risk,” Science, 236, 280-285.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Yin, R. K. (1989). Case Study Research: Design and Methods, Newbury Park, CA., Sage Publications.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Yin, R. K. (2003). Case Study Research: Design and Methods, London, SAGE.

Publisher – Google Scholar