Introductıon

“That human society is a marketplace, in which reputation are bought and sold”.

—Mark Fagel.

“Anything you lose automatically doubles in value, even more if it is reputation”.

—Mignon Mclaughlin.

Coping with uncertainty, crises and risks along with increasing openness and connectedness via new media have led public diplomacy to use «soft power» e.g., education, arts and culture, sports, science and technology more and to become more people-oriented. Likewise, companies have also emphasized such means of soft power through «corporate diplomacy» in line with their longer term strategic visions. Since demarcation lines between different target groups, stakeholders and sectors have also been blurred; SHRM has to take into account corporate diplomacy particularly in communication and branding topics that will influence reputation. In this vein, there is an agreement that organizational reputation, good governance with organizational trust are built from the inside-out(Martinet. al., 2011a; Martin, 2007 &2008; Mosley, 2007; Berens et. al, 2004).In this study, we will draw on previous research from reputation, branding and human resource management to develop a conceptual model of strategic human resource management (SHRM) with respect to branding and the role of social media, e.g., twitter and facebook. The implications for a holistic model suggest convergence of interest, but also highlight ethical dilemmas for organizations in balancing best practices of SHRM (Davies, 2008).

This article is an attempt to define organizational reputation as a multidimensional and an established appraisal about branding that is shared by multiple stakeholders that can provide the organization with an intangible asset that affects subsequent performance. Reputation in conjunction with branding may well be assessed from the organization’s perspective-from inside. In short, relationship marketing based on social capital (e.g., trust, teamwork, fairness, networking and identification) which often stem out of value-based talent management and corporate or employer branding are prerequisites for building the foundations for employee-oriented organization with good reputation from inside out (Martin et. al. 2011; Küçükkancabaş et. al, 2009). An authentic employer brand, which is being truly “an employer of choice” lives inside and it reflects to the minds of the candidates as the employees make it and live by its values, since employer brand is what the employees experience and tell the employer and stakeholders about their workplace rather than the other way around (Martin, 2008; Davis & Eisele, 2007).

In this present turbulent arena of business and commercial communication, there is a simultaneous concern for reputation, identity and brand management. The need for an operational definition of reputation as a strategic resource in communications and management studies with a stakeholder framework has been agreed upon in both fields. The ultimate goal is to provide conceptual and methodological clarities for future research that seeks to develop a better understanding of both organizational reputation and branding in the context of interdisciplinary understanding and practice(Huang, C. Y, 2011). Most of the research is on reputation risks and crises rather than benefits (Aula, 2010); some point out the importance of brand personality; however, linking it to constructs like brand commitment, trust and attachment of employees are overlooked. Others have selected only a particular segment of employees or managers as representatives. While trust, attachment and commitment to the brand-be it corporate, employer or internal-is rooted in brand personality, brand value propositions, which are also intangible stem from brand personality (Kaplan & Haenlein, 2010).

Reputation capital has rational, objective and functional components only to a limited degree. Yet, a significant portion of reputation is based on perceptions or expressive emotions of individuals, which are normative and subjective. Thus, different stakeholders may perceive reputations of the same company differently with respect to their various personal backgrounds. Reputation in conjunction with branding may well be assessed from the organization’s perspective-from inside (Davies, 2008; Davies & Chun, 2002).In short relationship oriented marketing and marketing communications along with strategic human resource management are prerequisites for building the foundations for customer-oriented organization with a good reputation from inside out (Huang, 2011).

While there are numerous studies on reputation management and measurement, the three main streams may be summarized to focus on perceptions about trust, social expectations and personality traits that people attribute either to their companies or to their brands (Berens and van Niel, 2004). The first two streams are concerned mostly with external stakeholders, whereas the latter is focused on the internal stakeholders, i.e., employees and the corporate personality. (Ibid). Although prior research has mostly emphasized company or organization identity, image or personality; there are few recent studies that emphasize branding (Amber & Barrow, 1996; Aaker, 1991 and 1997). Hardly, any has emphasized corporate branding along with employer branding along with internal marketing and communication or internal branding (Keller, 2008; Barrow & Mosley, 2005; Foster et.al., 2010). Even less research has linked employer branding with organizational or corporate reputation (Balmer, 2008).

As the employment environment have become progressively more dynamic, the organizations attempt for being the “employer of choice” by concentrating on employer branding (EB). Ambler and Barrow (1996) have defined EB as an employee value promise of all benefits offered to attract and retain them, which also means that the corporate brand image and reputation projected onto the prospective employees and the public (Davies, 2008). Based on Barrow’s theory of employer branding and internal employee communications, this relationship between reputation, branding and SHRM still represents a fertile area of further critical research since such policy-relevant research will focus on strategic leadership of core employees (Sparrow et al. 2003).

The presumption of employer branding enhanced by internal marketing is; however, to make customer-conscious employees handle services better by being aligned with business goals. That is why employees should be well-informed, empowered, trusted about a company’s offerings, brands and understand the strategies. How well do the employees identify with the “brand personality” is among the aims of employer branding. While brand personality is defined as the human features that may be attributed to a brand, how well the personality of the brand is communicated to the employees is at the crux of internal marketing communication. Then, employee behaviors will reflect an understanding of this brand personality (Yüksel & Kılıç 2013). In sum, we have attempted to reframe and rebuild organizational reputation with respect to employer branding in the context of emerging economies which are facing crises continually, if not continuously. Our focus is primarily on internal stakeholders particularly employees as both “internal customers” “brand representatives” of the organization. We have also looked into a few case studies as examples from Turkey as an emergent economy. By using structured interviews of selected employees of eight selected companies through structured interviews, we aimed at linking the theoretical framework with the empirical findings, while making suggestions for further query.

Theoretıcal Framework and the Conceptual Model

“Perception is conditioned by the tradition, in which its possessor has been reared”.

—Ruth Benedict.

With the widespread usage of digital technology, both reputation management and brand management are facing significant challenges lately. As social media has become more important, businesses have initiated relational marketing, brand management and internal marketing to the employment experience just like customer experience, particularly in practice. Among the limited academic research on employer branding and corporate reputation, the split between internal or external stakeholder, as well as corporate image versus corporate culture and personality are still salient. Therefore, we suggest that both brand management and reputation management are critical for strategic human resource management in this epoch of information and communication.

Due to the growing importance of identity in both branding/ marketing and human resource management literature and practice, in the next section, we have formulated a “brand alignment for reputation model” from the human resource management perspective (See Fig.1). Moreover, we propose that how the brand personality is perceived by employees is the common denominator of brand and reputation management. Since employees act both as brand ambassadors and reputation guardians who represent and promote their corporations’ brand, the values associated with the core employees have to be taken into account. That is why, brand image from the outside needs to be studied, and internal brand identity, particularly how brand personality is perceived by current employees needs to be studied as well. So, that companies can sell values and promises of the brands in this era of increased competition, instead of mere products or services, employees should know what they are doing along with and why they are doing. Therefore, before marketing and selling the brand’s promise to customers, companies need to communicate brand values to their employees first. (Nurmela, 2009; McLaren, 2011; Foster et. al, 2010).

Figure 1: A Framework for Contextualizing Reputation and Brand

Management For Social Media Platform

(P.S: The anchor/ pivot in the diagram is where the overlap of strategic management at three levels at the center is social media as the fundamental channel of corporate, marketing and commercial communication where employees as brand ambassadors are positioned; Yüksel, 2012).

How core employees use social media and electronic world-of-mouth (WOM) has combined reputation, marketing and human resource management perspectives (Fournier & Avery, 2011). Most of the research is on reputation risks and crises rather than benefits (Aula, 2010); some point out the importance of selecting a particular segment of employees as representatives (Kaplan & Haenlein, 2010). Interdisciplinary and brand new perspectives and models are essential to be able to explore how companies aim at building or preserving their brand and reputation particularly in new social media. Ambler and Barrow (1996) have introduced employer branding as a significant construct that can be operationalized and measured by applying brand management tools to strategic human resource management (Foster et. al. 2010). Inspired by Aaker’s(1991) emphasis of strong brands with static, sender focused inside-out notion employer brand DNA determined by corporate identity and personality, the focus of employer brand has been on different benefits that are functional, economic and psychological provided by the workplace (Aggerholm, et.al, 2011). Likewise, Balmer (2008) supported a strong corporate brand as the most significant navigational tool for key stakeholders including existing employees, shareholders, also potential employees due to the rise of service era. Employees are advocated as the interface between the organizations and the customers (Foster et. al, 2010; King & Grace, 2008 and 2012). They all suggest that delivering the corporate brand promise and employer brand promise is derived from understanding the corporate culture and identity.

Adding potential employees as a key stakeholder into corporate branding is more recent with the comprehension that employer branding and its relation to two types of branding: Internal and corporate branding. Internal branding is the third concept related with internal marketing and communication as it pertains to the fulfillment of the corporate brand compromise through consistent delivery by employees (Foster et. al., 2010; 402). Following Foster (2010) and Aggerholm (2011), we have reconceptualized the employer branding from a more social-constructivist HRM perspective with primarily two stages of development: managing employee perceptions of the brand personality first, and then managing the employee value propositions of the employer brand for building trust and commitment.

Prahalad and Ramaswamy (2004) have defined the market as “a forum for conversations and interactions” between consumer citizens, partners or other employees, and changed “the locus of firm-centric economic value extraction into a locus of co-creating values” (Foster et. al, 2010). From the strategic employer branding standpoint, this can be interpreted as a move from a linear, static transmission of value promises and benefits from the employer as the sender within working hours into a 24/7 process of co-creating not only economic, functional and psychological values pertaining to the workplace, but also a concern of what is valuable, responsible and meaningful (Ibid.) With increasing significance of social media in corporate communications, the construct of co-creating values / promises fosters a major shift in brand management and stakeholder relationships. It opens up an interactive and dynamic venue for a bundle of possible customized value-added services, designs and experiences (Prahalad and Ramaswamy, 2004; Foster et. al, 2010).

The underlying premise of this redefinition is that employer branding has contextualized branding, as well as reputation management since corporate priorities and norms and policies may change depending on the conjunctures; for instance, the brand promises in times of prosperity may be different from those in times of crisis. That is why, we have to redefine the prior static notion of value proposition in employer, corporate and internal branding as an universal principle, and realize that continuous renegotiation of values with stakeholders with respect to changing stakes and expectations may even translate into changing corporate culture and identity (Aggerholm, 2011; 113-118; Prahalad and Ramaswamy; 2004). Such “a process and internal stakeholder focus” demand an enactment of new sustainable relations between the organization and its current and potential employees. For instance, to sustain trust and fairness within organization among employees in turbulent times especially in emerging economies have to be continuously maintained (Foster et. al, 2010).

As Berens and van Riel (2004) have outlined, among the major schools of reputation management literature, either perceptions are often measured on the basis of social expectations or on the basis of creditworthiness of companies; however, they are both contextual. Only the last school of thought, which is on corporate identity and corporate personality traits that are attributed to companies, is long lasting and employed widely with minor adaptations in different contexts. Yet, in both conceptualization and operationalization of corporate identity and personality, there are disagreements due to differences in actual, communicated, conceived, ideal, and desired identity along with the fact that an outside-in approach from an external stakeholder view that is external identity predominates. Consequently, the corporate image of receivers rather than corporate culture and identity is often highlighted. In this vein, the confusion between corporate, organizational and visual identity and the ambiguity regarding the organizational personality concept as summarized by Balmer (2001) have limited our inquiry to corporate reputation that poses the question: What distinctive attributes are assigned to a particular organization? In addition to considerable disagreement in the literature on corporate culture and identity, determining to what extent employees may be aligned with corporate identity and whether it is functional or is not debatable (Nair, 2010)..

According to Chun’s (2005) categorization of the operationalized version of reputation, there are three major areas of empirical research: the evaluative, the impressionist and the relational school. The first focuses on a top-down financial performance from the perspective of investors and managers, the second concentrates on single stakeholder about the overall impression of the organization, while the last one emphasizes the perception gaps between internal and external stakeholders. The third view paves the way for a comparative approach and makes the distinction between creating a favorable external and internal recognition; yet, it neither suggests stages of reputation development, nor proposes where to start. We have; therefore, focused mainly on the branding and its relation to reputation management from an inside-out approach with internal stakeholder view.

Instead of regarding employers, corporate and internal branding as static outcomes, analyzing branding processes, e.g., communication as a dynamic and interactive process(as in social media) still from the sender aspect (e.g. in social media with respect to branding and reputation management) may pave the way for exploring what an interactive dialogue between employer and employee would mean in the near future. Regarding brand personality as the anchor of streams of brand management for reputation may aid us in making employees understand and experience the brand personality in their dialogues, so that there would be congruence in corporate, employer and internal brands ( Yüksel, 2012; See Fig. 2). Due to the need for consensus between branding and reputation management perspectives particularly in the social media platform, we developed “the brand congruence model from internal stakeholder perspective”, since there are few studies on this topic and none of them are from human resource management perspective (Deans, 2011).

In short, we advocate that emplacing the brand personality would frame the perceptions of employees since it would make them think of the brand as if it were a human being and it would distinguish the attributes that make them different from their competitors. Second, we suggest that a corporate culture stressing mission, vision and values and how these affect employees’ attitudes and behavior would be significant for corporate reputation. The rest of the attributes of brand identity such as self-image, visual identity, relationships etc. would come after these two pivotal aspects are studied (Kapferer, 2004; Nurmela, 2009).

Figure 2: A Model on Brand Congruence for Reputation Management (Yüksel, 2012)

(P.S: The anchor/ pivot in the model is where the overlap of three brands is, i.e. brand personality).

One of the underlying assumptions of employer branding coincides with the resource-based view that emphasizes developing unique internal resources (Backhaus and Tikoo,2004 cited in Sarabdeen, J. et. al, 2011), supporting the claim that employer branding is a means to win the war for talent. The second perspective is emotional and symbolic framework that also provide a basis for the notion of employer branding (Lievens and Highhouse, 2003;Sarabdeen, J. et.al. 2011). Based on the brand image of the employer and the employer reputation, employees create their perceptions of the brand. The third theory is the instrumental and functional framework that is based on rational expectations and preferences. Of course, an employer brand ought to take into account all three assumptions and formulate human resource policies accordingly (Lievens, F. Greet &Anseel, 2007, Sarabdeen, J. et. al, 2011)).

All perspectives suggest that delivering the corporate brand promise and employer brand promise is derived from understanding the corporate culture and identity. Adding potential employees as a key stakeholder into corporate branding is more recent with the comprehension employer branding and this relation between two types of branding (Foster et. al. 2010). Internal branding is the third concept related with internal marketing and communication to fulfill the corporate brand compromise through consistent delivery by employees. Following Foster (2010) and Aggerholm (2011), we have reconceptualized the employer branding from a more social-constructivist HRM perspective with primarily two stages of development: managing employee perceptions of the brand personality first, and then managing the employee value propositions of the employer brand (Love & Singh, 2011; 177). While in marketing, brand loyalty is mainly the attachment that delineates how a consumer feels about a specific product and service; in HRM, it is the commitment that both current and prospective employees provide to the employer, which is driven by the value that employees derive from the total work experience (Ibid.). Further, the employee’s understanding of employer brand adds an additional value (McLaren J.P. 2011; 208).

Following Ehnert’s (2006) Sustainable Human Resource Management perspective, we have revised and combined our understanding of corporate reputation within the framework of employer branding and talent management.

Although reputation may also be studied as corporate, organizational / workplace and social reputation, we have based our model mainly on corporate reputation as an integral part of corporate and employer branding, so that it is also aligned with brand personality (Fig. 2). People have tendency to grant human traits onto non-human entities such as organizations and brands; that way, the significance of current employees as both brand ambassador and reputation guardian is acknowledged for employees deliver the brand promises to customers (King and Grace, 2008). Although the brand personality dimensions of Aaker do not always fit the cultural context, the brand personality framework with its premises in Fig. 4 is universal. The critical point here is there should be an integrated marketing communication (IMC) as well as a coordinated internal communication to create positive reputations; in other words, they need to have a commoncore, such as an internalized brand personality. Additionally, they need to stem from a corporate story, which combines the conflicting demands of external and internal stakeholders over time. That it why, it is argued that the success of employer branding depends on creating a realistic analysis of the external and internal brand propositions, that is employer value propositions and unique selling propositions. Only then, aligning these two they are aligned and synhronized through core employee values (Davies, 2008; Martin et al. 2011b, Sparrow, 2008).

Empirical Analysis: Methodology and Findings

Methodology& Sample

Prior empirical research on reputation has shown that social media platforms offer challenges and risks mostly from the external stakeholder perspective. In this article, however, we have looked into the process of reputation and branding in social media, focusing on the process of brand ambassador role of current employees in a number selected companies with respected brands from three significant sectors in Turkey as an emerging market: High-tech industries (3), airways (2) and finance sector (3).

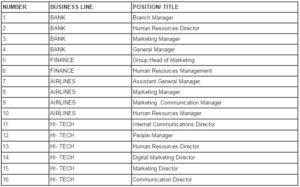

This exploratory research is based on structured interviews of sixteen employees from top management that have been conducted between 2011-2012-; the titles are listed in the Appendix 1.The semi-structured interview questions revolve around the research question as to what the role of key employees are as brand ambassadors and reputation guardians. What are the checks and balances of authorization of employees and what are the leverages of internal brand management and on-line customer dialogue? We approached twice the number of companies; however, we were able to contact with managers from half of them throughout a year. We have made face-to-face interviews about an hour with 16 managers from eight different companies, so the sample is representative of these sectors even if the size is small.

The two banks are larger in the number of branches. We have an additional successful mid-sized brokerage house from the finance sector. The two commercial airlines are both medium sized domestic companies; one of them was founded in nineties, the other ten years later. As for the three high-tech companies, one is a wide-ranging retail chain, the other two are largest GSM operators- one of them has a global brand, while the other has a domestic brand. In all these companies, top executives and key managers of the branding process are consulted (See the List in the Appendix 1). Arranging meetings with top-level managers were carried out with the support of two graduate students who were employees in these sectors-high-techs and banking; the managers from the airlines have been interviewed during the career center seminars at Kadir Has University first, and a second meeting has been arranged at their sites later.

The most time consuming part of the research was, indeed, conducting and interpreting these interviews through comparing and analyzing similarities and differences with respect to key topics addressed. We encountered more difficulty in both making the organization with the interviewees from high-tech industries and airlines as well as getting information about the research. It is probably related with the fewer number of rivals and high levels of competition in these business lines. We have concealed the company names to be able to get information and proceed with our research. By and large, we had the interview time of 45 to 60 minutes and some of the responses were restricted by interviewees themselves.

Summary of Findings

“A brand is not a product or a promise or a feeling. It’s the sum of all the experiences you have with a company.” —Amir Kassaei

All our interviewees from eight companies believe in the brand ambassador role of core employees and the positive impact of reputation on performance. All companies officially use both Facebook and Twitter. They also have call centers; however, almost all interviewees emphasized the differences between the role of call centers, on-line services and social media-the first is reactive intermediary role based on past issues, service failures or quality gaps of expectations at operational levels of individual customer services for maintenance; the second is focused on direct e-services, whereas the latter provides preventive or comprehensive information at either strategic or tactical levels for improving current and future service quality. Unlike call centers, they have a significant impact on the perceptions of targeted stakeholders not only about the service, but also regarding the company reputation.

In short, dialogue through social media is directly linked with the reputation and brand management in all companies despite the fact that the framing and contexts are different in each sector, as there are differences between their lines of business as regards the extent of social media adoption. Finally, we have found that size matters, and the employees of large scale companies in these three sectors have more restrictions as compared to medium sized ones. Small sized firms have been omitted from our sample since we were not able to arrange meetings with them. The level of competition based on the number of rivals (e.g., banks have large number of competitors as compared to the other two sectors).The issue is not only from where to focus, but how to combine narrating, messaging and acting authentic, that is, being good as well as looking good. This is not easy for more established sectors with larger sizes such as banks and telecommunication, or even in large scale airway alliances, which already have recognized brand names. It is more convenient for new services like- in our case- the airlines that are new entrants to the sector.

Diverse Approaches towards the Presence of Twitter and Facebook

During the interviews at the three different financial institutions (two banks, one broker house), the interviewees stated they all have their profiles in Facebook, but not all in Twitter (only one); they also said they use social media rarely. Their doubtful responses revealed lack of trust and concern for privacy. The senior managers of the banks also stated that there are special units for arts and cultural events of their banks and they are active in social media with the customers. They believe that sponsorships, voluntary social responsibility activities of employees along with relationships with customers through social media platforms have to be separate from the main services and operations of the banks.

In the hi-tech industry, excluding the retail stores, social media is the primary channel for reputation building and developing. The employees are encouraged through relevant position managers to act as brand ambassadors both between and among the dialogues of employees along with customers. However, professional media agencies carry out the social media campaigns and reporting of customer’s complaints or requests. The company site and blogs and open forums are up-dated by most of the key employees. There is an active sharing of information especially within the company. There are incentives by their academies as well as the relevant divisions; however, there are some limitations set through norms and policies with respect to external stakeholders.

While customer security requires a cautious attitude to social media at banks, the top-level executives stated the difficulty of having long-term goals. In contrast, the high-tech firms emphasized internal marketing and branding as well as internal communication through social media platforms. There were sanctions, disclosure policies and norms concerning latest services or innovations since there are severe competition between rival companies, which are all large sized. At the two airlines, the managers definitely saw the significance of interactive dialogue with current and prospective customers, as well as the importance of regarding employees as brand and reputation ambassadors. The rivalry is different in this sector (particularly among smaller scale domestic airlines), and the promises offered to customers and employees are based on relational marketing with a long-term vision. Thus, there is more long range planning and clearer objectives paving the way for more transparent and interactive marketing communication among the managers.

Although the awareness of internal branding and marketing was higher in the high-tech firms, there was more emphasis on the opportunities offered by social media networking as an arena for brand and reputation building according to the responses of interviews in airlines. One even stated that picking up the latest rumors through networks and controlling them may be important in crisis management. Yet, social media strategies and campaigns are often planned together with outsourced media agencies as was the case with the high-tech industries.

We have found that, in principle, almost all sixteen interviews revealed the significance of employees in both brand and reputation building as well as sustaining. Consequently, all managers mentioned the brand and/or reputation ambassador role of employees. How active the employees should be in the social media during working hours and outside working hours was another issue that was raised. Although most companies emphasize using social media network only during employees’ free time, high tech industries allow and even encourage its usage at work; however, for internal purposes mostly, including employees or suppliers.

Notably, one branch manager of a bank stated that the content of communication has “to reveal high profile and there cannot be too many different voices that may lead to confusion rather than persuasion”; while another noted the importance of being tactful and discreet to avoid risks. Since financial services operate in a tightly regulated environment, employees cannot respond naturally and real-time as other industries or services said another manager at the broker house. In the hi-tech industries, key employees are permitted to contribute to dialogues on social media platforms also within the confines of rules and regulations. Tweeting and broadcasting too much, or showing always a high-profile format or being aggressive or being conspicuously company-promotional when trying to act as an ambassador might have negative side effects or even a boomerang effect at times, according to the managers from the high-tech industry. Balancing self-promotion with company-promotion seems to be possible only through being personal and having multiple voices; therefore, reputation at times may be managed by key employees such as top executives only to a limited degree. Yet, building brands particularly through internal and employer branding, starting with recruitment and going on in all functions of human resource management are all significant, as suggested by a human resource director of a high-tech industry.

By and large, gaining visibility in social media through the support of key employees in conjunction with the guidelines of the company as well as the outsourced media agency is favored in both high-tech industries and airlines. As Turkey is one of the most connected countries with a large size of young consumers, short-term twitter or facebook campaigns with embedded games/ contests for promotion and sales for e.g., flight tickets or smart phones are common. The value of engaging employees in social media as brands and building short-term relations, which may lead to transaction of sales, is often still more favored than relational marketing. There are alternative interactive services that even integrate the TV screen with the digital experience of internet services. The goal is to actively involve more consumers, and make the brand communication more efficient, both in the short and long term.

Even if the impact of social media is appreciated and digital media agencies are used by most of the companies for marketing communications, still its internal usage is limited due to the lack of trust; however, top executives are aware of the fact that they can benefit from employer branding as brand identity and personality among their employees. As some of the managers from the high-tech industries noted strategic innovative aspects rather than administrative or engineering aspects within companies make the difference of success in building employer branding and reputation. Yet, their sustainability depends on engineering methods and tactics about processes and solving operational issues.

While the inside-out approach is preferred by most top executives that we have interviewed, whether the senior managers themselves should build and maintain long-term relations with key customers is still being questioned. Finally, embedding the branding with consistence, integration, and alignment with HRM functions and responsibilities has to be supported either by one management team or by one of the board members. Branding should be embedded by anchoring it in the culture of organization and the behavior of its employees according to what we have noticed in most of the companies that we have visited and observed. Only then, focusing on the image of the organization on external stakeholders may become meaningful. The possibility of simultaneous management of both seems to rely upon measuring and managing social media efforts of organizations with a service concern rather than a control concern, as implied by all managers.

Concluding Remarks

“You do not attract who you want or who you want to be; you attract who you are.”

— John Maxwell

Based upon the empirical insights on both brand management and reputation management that may be derived from the three growing sectors that particularly use social media intensively, there are both similarities and differences in the perspectives of these selected sectors: financial services, hi-tech industries including its retail, airline companies. They are all aware of the challenges and risks involved in extensive and uncontrolled usage of social media; therefore, they suggest that only key employees at upper echelons should be approved as brand ambassadors or reputation guardians in social media interface of companies. However, there are discrepancies as how to balance the process of empowerment and control those key employees in their on-line dialogues with respect to services provided, as well as the personal relations.

On the whole, the size of the companies and the nature of the sectors seem to matter in determining the extent of active participation of employees in social media. In general, control is still more emphasized than service; consequently centralized responsibility and a hands-off policy on risky matters are preferred styles of management. There are broad differences with respect to their distinct branding content in social media, which might stem from their brand personality differences, which we have not analyzed in detail here. Yet, we noticed that authenticity, sincerity and transparency of content are the main dimensions that all interviewees have emphasized. Some have highlighted excitement, bravery, and innovation. Further look into these differences of brand personality may reveal more about the variations about the different aspects of reputation.

The integrative focus of corporate branding and reputation places a significant role on both internal branding, marketing as well as on employer branding. The premise behind is that employees play an important part in company brand promise. That is why, conveying brand values to both employees as internal customers and other outside customers are all significant. Prior research has addressed the threats and opportunities of social media platforms and viral marketing through online word-of-mouth from either product, service or customer-centric views, ignoring employees and their role (Fournier & Avery, 2010; Aula, 2010).

In reality, even our preliminary findings of firms that are at the infancy of social media usage delineate the fact that employees play a substantial role even in such limited and controlled contexts. Companies such as high-tech telecommunication and airlines emphasize authenticity and transparency in direct communication, stating that brand and reputation management is more significant than the possibility of negative online word-of-mouth or other risks that social media may stimulates as a side effect. Others such as in financial services, are more prudent as to be anticipated, and management of the banks’ overall social media presence is mostly limited to the official sites. Yet, there is full trust only in key employees at the banks selected for this study, which might be related with the precautious nature of recruitment policies. Only at airlines were top managers allowed a personal style in their private sites, as well as official sites. They work collaboratively with a number of digital media agencies for different purposes. Since employees’ private sites are also considered, using an official or branded language cannot be possible. Top-down and integrated brand management seem to be difficult in controlling social media.

In a nutshell, this preliminaryresearch explored relationship between corporate reputation and branding, and SHRM represents a fertile ground for further research. The sample size, qualitative and cross-sectional method employed hereare the limitations of this study. Quantitative analysis with a larger sample may enhanceour findings. Comparisons between different sectors, regions andcountries may reveal interesting positioning strategies and balancing tactics in international human resource management. With the increasing expertise in social media and storytelling to their target audience who are at times authors, both an inside-out perspective as suggested here and an outside-in view may be useful (Ulrich, 2009). The issue is not only from where to focus, but how to combine narrating, messaging and acting authentic, that is, beeing good as well as looking good. That is to say, one has to have inside-out method with an outside-in mentality or vice versa.

Future research that focus on small sized media agencies, consultancies, research firms or arts and cultural services foundations may delineate completely different manner of understanding and managing brands and reputation online due to their business lines and sizes. Longitudinal analyses may reveal the entire process of both building and sustaining reputation management. As stated in the Employer Branding Global Research Study (2011): “Today we have to learn to actively listento what is being said about us and we can no longer control the message. Even just by using social media appropriately as recruiting and talent management,employee engagement, feedback (to and from both employees and customers), learning and development tools, human resource managers can enhance employer branding and corporate reputation simultaneously…”(Bondarouk et. al, 2013). Martin, 2007).

By and large, organizational success, climate, culture as well as brand reputation, personality and quality of products and services are significant factors for all employees. In the strategy of becoming the employer of choice by employees as the captive audience as opposed to prospective candidates is important for branding with an inside-out approach. Following the Cornell architectural approach (Lepak & Snell 2002), employee segmentation and targeting specific employees may be possible. By identifying bundles or factors of employee value propositions, an exclusive talent management of the key employees may be applied. That way, core knowledge employees adding high reputation value as brand ambassadors may be treated with more care. Such specialization of employer branding, which highlights fitness of people-brand values and brand personality that revolve around brand appeals and perceptions of employees are at the crux of strategic brand management: How to balance star performers with the rest of the maintaining employees, so that individual human capital and social capital e.g., trust, teamwork, and bonding are equally important, so that cultural sustainability is maintained. Maintaining a high performing corporate culture in the long run demands leadership and talent management with 360 degrees of feedback system aligned with an authentic employer branding (Atlı, 2012; Baş, 2011).

Overall, employer branding may be perceived as a response of strategic human resource management to both competitiveness and crises in global economy, and the particular market circumstances of emergent economies. However, employer branding has to be handled with care and attention (Gaddam, 2008). In Turkey employer branding efforts have been observed as well, and 53% of the companies have claimed to focus on executive or leadership development programs; yet neither the increased role of social media with due respect to employer brand and reputation management, nor the significance of strategic and sustainable human resource management is comprehended to the same extent (EBI, 2011).

With social media, visual brand identities and brand images as public representations and perceptions of reality cannot be based solely on impression management; strategic human resource management and leveraging of internal stakeholders as (employee or employer) brand advocates are required for cultural sustainability and continual, if not continuous brand reputation and value branding proposition. While employer branding creates wide spread networking with stakeholders, social media will enhance the role of human resource managers’ collaboration with marketing, public relations as well as their networking skills even more in the near future (Bondarouk et. al, 2013; Gaddam, 2008: 55). As Senge states: “The organization that will truly excel in the future will be the organizations that discover how to tap people’s commitment and capacity to learn at all levels in an organization” (1990:4). Adding to this, we have added that experience of employers employee value propositions along with their perceptions of employer brand personality determine the reputation of employer brand, while leveraging the talent of core employees, which act as brand ambassadors.

Appendix 1

Table 1: The List of Interviews Conducted Between 02/2011 to 09/2012

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

References

1. Aaker, D.A. 1991. Managing Brand Equity: Capitalizing on the Value of a Brand Name. N.Y: The Free Press, 1991.

2. Aaker, D. 1996. Building Strong Brands. New York: The Free Press.

3. Aaker, J.L. 1997. Dimensions of Brand Personality, Journal of Marketing Research, 34. August, 347-356.

Publisher – Google Scholar

4. Aaker, David A. 2009a. Marka Değer Yönetimi (Brand Value Management). Trans.. Ender Orfanlı. İstanbul: MediaCat Kitapları.

5. Aaker, David A. 2009b. Güçlü Markalar (Strong Brands). Trans. Erdem Demir. İstanbul: MediaCat.

6. Aggerholm, H. K, Andersen, S. E. and Thomsen, C. 2011. Conceptualizing Employer Branding in Sustainable Organizations, Employer Branding, Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 16. No. 2. Emerald Group pub. : 105-123.

7. Ambler, T. and Barrow, S. 1996. The Employer Brand. Journal of Brand Management, 4: 185-206.

Publisher – Google Scholar

8. Aula, P. 2010. Social Media, Reputation, Risk and Ambient Publicity Management, Strategy and Leadership, 38 (2):43-49.

Publisher – Google Scholar

9. Austin, R. Jon, Judy A. Siguaw ve Anna S. Mattila. 2003. “A Re-Examination of the Generalizability of the Aaker Brand Personality Measurement Framework,” Journal of Strategic Marketing, 11 (2): 77-92.

Google Scholar

10. Atlı, Dinçer. 2012. Yetenek Yönetimi (Talent Management),İstanbul: Krea.

11. Backhaus, K. ve Tikoo, S. 2004. ”Conceptualizing and Researching Employer Branding”, Career Development International, 9 (5) 501-517.

Publisher – Google Scholar

12. Balmer, J.M.T. 2008. Identity-based Views of the Corporation: Insights from Corporate Identity, Organizational Identity, Social Identity, Visual Identity, Corporate Brand Identity and Corporate Image. European Journal of Marketing, 44. No.3-4: 248-291.

Google Scholar

13. Barrow, S. ve Mosley, R. 2005. The Employer Brand: Bringing the Best of Brand Management to People at Work, N.J.: John Wiley and Sons Ltd.

14. Baş, Türker. 2011. İşveren Markası (Employer Branding). İstanbul: Optimist.

15. Beatson, A.; Lings, I. ve Gudergan, S. 2008, “Employee Behavior and Relationship Quality: Impact on Customers”, The Service Industries Journal, 28(2), 211-224.

Publisher – Google Scholar

16. Berens, G. & van Riel, B.M.2004. Corporate Associations in the Academic Literature: Three Main Streams of Thought in the Reputation Measurement Literature. Corporate Reputation Review,7. No.2: 161-178.

Publisher – Google Scholar

17. Blanchard, Olivier. 2011. Social Media ROI: Managing and Measuring Social Media Efforts in Your Organization. Boston, M.A.: Pearson Edu. Inc.

18. Bondarouk, T. Ruel H. Axinia, E. and Roxana Arama. 2013. “What is the Future of Employer Branding through Social Media? Results of the Delphi Study into the Perceptions of HR Professionals amd Academics”, Chapter 2, Social Media in Human Resource Management, Advanced Series in Management, Emerald Group Pub., 23-57.

Google Scholar

19. Cardy, Alan. 2012. “Organizational Reputation: Issues in Conceptualization and Measurement”, Corporate Reputation Review, 15(4): 285-303.

Publisher – Google Scholar

20. Chiavenato, Idalberto. 2001. “Advances and Challenges in Human Resource Management in the New Millennium”; Public Personnel Management, 30(1): 17-27.

Google Scholar

21. Chun, R. 2005. “Corporate Reputation: Meaning and Measurement”, International Journal of Management Reviews,7: 91-109.

Publisher – Google Scholar

22. Davies, G. 2008. “Employer Branding and Its Influence on Managers”, European Journal of Marketing, 42 (5/6), 667–681.

Publisher – Google Scholar

23. Davies, G. & Chun, R. 2002. “Gaps between the Internal and External Perceptions of the Corporate Brand”, Corporate Reputation Review, 5 (2/3):114-158.

Publisher – Google Scholar

24. Davis, P. & Eisele, M. 2007. “The View Form Inside: People Power through Internal Marketing” Journal of Integrated Marketing Communications, 47-55.

25. De Chernatony, L. 2001. From Brand Vision to Brand Evaluation: Strategically Building and Sustaining Brands. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann Ltd.

26. Deans, P.C. 2011. The Impact of Social Media on C-level Roles: MIS Quarterly Executive,10. No. 4: 187-200.

Google Scholar

27. Deephouse, David L. and Suzanne M. Carter. 2005. “An Examination of Differences Between Organizational Legitimacy and Organizational Reputation”, Journal of Management Studies, 42 (2), March 2005.

Google Scholar

28. Doyle, Peter. Değer Temelli Pazarlama (Value-based Marketing). Trans. Gülfidan Barış. İstanbul: MediaCat.

29. Dölarslan, E. Şahin. 2012. “Bir Marka Kişiliği Ölçeği Değerlendirmesi”, SBF Dergisi; 67 (2): 1-28.

30. EBI 2011, Employee Brand International Report, Employer Branding Global Research Study.

31. Edwards, Martin R. 2010. “ An Integrative Review of Employer Branding and OB theory”, Personnel Review, 39 (1): 5-23.

Google Scholar

32. Ehnert, Ina. 2006. “Sustainability Issues in Human Resource Management”, SHRM Workshop, Ashton: Birmingham.

33. Ewing, Michael & A. Caruana. 1999. “An Internal Marketing Approach to Public Sector Management: The Marketing and Human Resources Interface”, the International Journal of Public Sector Management: 12 (1): 17-26.

Google Scholar

34. Foster, C., Punjaisri, K. & Cheng, R. 2010. “Exploring the relationship between Corporate, Internal and Employer Branding”, Journal of Product and Brand Management, 19. No. 6: 401-409.

Publisher – Google Scholar

35. Fournier, S. and Avery, J. The Uninvited Brand. Business Horizons, 54. No.3. 2011: 193-207.

Publisher – Google Scholar

36. Gaddam, Soumya. 2008. “Modelling Employer Branding Communication: The Softer Aspect of HR Marketing Management”, the Icfai University Press, Hyderabad: 45-55.

37. Gulati, R. 2007. “Silo Busting: How to Execute on the Promise of Customer Focus”, Harvard Business Review, May, 98-108.

Google Scholar

38. Herzberg, F.I. 1987. ‘One more time: How do you motivate employees?’, Harvard Business Review, Sep/Oct, Vol. 65 Issue 5: 109-120.

39. Hofstede, G. 1993. “Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind”, Administrative Science Quarterly.38 (1): 132–134.

40. Huang, Yi-Hui C. 2011. “Organizational Reputation: A Perspective on Public Relations Value”, InternationalAssociation of Media and Communication Research (IAMCR),Kadir Has University, Istanbul.

Publisher – Google Scholar

41. Jussila, Jari Juhani, Karkkainen, H. and Leino, M. 2011. “Benefits of Social Media in Business-to-Business Customer Interface Innovation”,MindTrek, Sept. 2011, Finland; 28-30.

42. Kaplan, A.M: and Haenlein, M. 2010. Users of the World Unite! The Challenges and Opportunities of Social Media. Business Horizons, 53. No. 1: 59-68.

Publisher – Google Scholar

43. Kapferer, J. 2004. The New Strategic Brand Management: Creating and Sustaining Brand Equity Long Term. 3rd ed. London: Kogan Page.

44. Keller, K. 2008. Strategic Brand Management – Building, Measuring, and Managing Brand Equity. 3rd ed. New Jersey: Pearson International.

45. King, C. and Grace, Debra. 2012. Examining the Antecedents of Positive Employee Brand-related Attitudes and Behaviors”, European Journal of Marketing, 46 (3/4): 469-488.

Publisher – Google Scholar

46. King, C. and Grace, D. 2008. Internal Branding: Exploring the Employee’s Perspective. Journal of Brand Management, 15. No. 5: 358-72.

Publisher – Google Scholar

47. Küçükkancabaş, S, Akyol, A. and Ataman, B.M. 2009. “Examination of the Relationship Marketing Orientation on Company Performance”, Quality and Quantity, Vol. 43, No. 3: 441-50.

Publisher – Google Scholar

48. Lengnick -Hall, Mark and Lengnick-Hall, Cynthia. 1999. “Expanding Customer Orientation in the HR Function”; Human Resources Management; 38 (3): 201-214.

Publisher – Google Scholar

49. Le Pla, Ruth. 2007. “Employment Branding: Who’s Responsible? Employment Branding has been embraced by the Human Resources Specialists. But should it be the Preserve of the Marketing Department?” Marketing Magazine 16; Dec.

50. Lepak, D. & Snell, S. A. 2002. The strategic management of human capital: determinants and implications of different relationships. Academy of Management Review, 24, 1-18.

51. Lievens, F. Greet Van Hoye and Frederik Anseel .2007. “Organizational Identity and Employer Image: Towards a Unifying Framework”, British Journal of Management, 18: 45–59.

Publisher – Google Scholar

52. Lievens, F. & Highhouse, S. 2003. “The Relation of Instrumental and Symbolic Attributes to a Company”s Attractiveness as an Employer,” Personnel Psychology, 56, 1, 75-102.

Publisher – Google Scholar

53. Love, Linda F. & Singh, P. 2011. “Workplace Branding: Leveraging Human Resource Management Practices for Competitive Advantage through ‘Best Employer’ Surveys”, Journal of Business Pscyhology. 26: 175-181.

Publisher – Google Scholar

54. Martin, G. & Hetrick, S. 2006. Corporate Reputations, Branding and Managing People: AStrategic Approach to HR, Oxford: Butterworth Heinemann.

55. Martin, G. 2007.Employer branding: time for a long and hard look? In CIPD, Employer Branding: the latest fad or the future of HR? London: Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development.

56. Martin, G. 2008. “Driving Corporate Reputations from the Inside: A strategic Role and Strategic Dilemmas for HR?” University of Glasgow Working Paper, www.mngt.wikato.ac.nz (Accessed on April, 2nd, 2015).

57. Martin, G., Gollan, P. J., Grigg, K. 2011a. “Corporate Governance and Strategic Human Resources Management (SHRM) in the UK Financial Services Sector: The Case of the RBS”, http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/43527(Accessed on March 25, 2015).

58. Martin, G. Gollan,P. J., Grigg, K. 2011b. “Is there a bigger and better future for employer branding? Facing up to innovation, corporate reputations and wicked problems in SHRM”, International Journal of Human Resource Management, 22 (17). Pp. 3118-3637.

Publisher – Google Scholar

59. Maslow, Abraham. 1954. Motivation and Personality. New York: Harper.

60. McLaren J.P. 2011. Mind the Gap: Exploring Congruence between the Espoused and Experienced Employer Brand. An unpublished Dissertation Thesis, University of Pennyslylvania, October.

Google Scholar

61. publications.theseus.fi. (Accessed on March 8th, 2015).

62. Montgomery, D. ve Ramus, C. 2011. “Calibrating MBA Job Preferences for the 21st Century”, Academy of Management: Learning & Education, Mart 10 (1): 9-27.

Google Scholar

63. Morgan, R. &Hunt, S. 1994. “The Commitment-Trust Theory of Relationship Marketing”, Journal of Marketing, 58, 20-38.

Publisher – Google Scholar

64. Mosley; Richard W. 2007. “Customer Experience, Organization Culture and the Employer Brand”, Journal of Brand Management, 15: 123-134.

Google Scholar

65. Nair, N. 2010. Identity Regulation: Towards Employee Control? International Journal of Organizational Control, 18. No.1: 6-22.

Publisher – Google Scholar

66. Nolan, Kevin P. Gohlke, M. Gilmore, J. and Ryan Rosiello. 2013. “ Examining How Corporations Use Online Job Ads to Communicate Employer Brand Image Information”, Corporate Reputation Review, 16: 300-312.

Publisher – Google Scholar

67. Nurmela, H. 2009. Internal Branding in High Technology Environment. An unpublished Thesis, Jamk University of Applied Sciences, October.publications.theseus.fi. (Accessed on March 8th, 2015).

68. Prahalad, C. K. and Ramaswamy, V. 2004. Co-creation Experiences: The Next Practice in Value Creation; Journal of Interactive Marketing, 18. No.3: 5-14.

Publisher – Google Scholar

69. Rafiq, M. Pervaiz, K.A. 2000. “Advances in the internal marketing concept: definition, synthesis and extension”, Journal of Services Marketing, 14 (6): 449-457.

Google Scholar

70. Realta 2011. En Gözde Şirketler. (The Most Admired Companies to Work for). Humanist: İstanbul.

Publisher – Google Scholar

71. Sarabdeen, J. El-Rakhawy, N. and KhanAli, H. N. 201. Employer Branding in Selected Companies in United Arab Emirates, Vol.2011 Communications of the IBIMA, 9 pp. www.ibimapublishing.com (Accessed on March 5th, 2015).

Google Scholar

72. Sartain L. & Schumann M. 2006. Brand from the Inside, CA San Fransisco: Jossey Bass.

73. Simoes, C.,Dibb, S. & Fisk, R. 2005. Managing Corporate Identity: An Internal Perspective. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 33.No. 2: 153-168. (Accessed on Dec. 27th, 2012).

Google Scholar

74. Sparrow, P. R. & Cooper, C. L.2003.The New Employment Relationship. Oxford: Butterworth Heinemann.

75. Senge, Peter. 1990. The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization. New York: Doubleday.

76. Sincic, D. ve N. P. Vokic. 2007. “Integrating Internal Communications, Human Resource Management and Marketing Concepts into the New Internal Marketing Philosophy”, University of Zagreb Working Paper Series, 7 (12):1-13.

Google Scholar

77. Tüzün, İ. Kalemci, and Tülay Korkmaz Devrani, 2008. “Müşteri Memnuniyeti ve müşteri-çalışan etkileşimi üzerine bir araştırma”, Eskişehir Osmangazi Üniversitesi İktisadi ve İdari Bilimler Fakültesi Dergisi, 3.2: 13-24.

78. Tüzüner, V. L. & Yüksel, S.A. 2009. ”Segmenting Potential Employees according to Employer Attractiveness Dimensions in the Employer Branding Concept”, Journal of Academic research in Human Resources Management, 1, 47-62.

79. Ulrich, D. 2009. HR Transformation:Building Human Resources from the Outside in. New York: McGraw-Hill Co., RBL Institute.

80. Varey, R. J.1995. ‘Internal marketing: A review and some interdisciplinary research challenges’, International Journal of Service Industry Management 6 (1): 40-63.

Publisher – Google Scholar

81. Viardot, E. 2004. Successful Marketing Strategy for High-Tech Firms. 3rd ed. Norwood: Artech House.

Google Scholar

82. Wayne, J. H. and Casper, W.C. 2012. “Why does firm reputation in Human Resource Policies Influence. College Students? The Mechanisms Underlying Job Pursuit Intentions” Human Resource Management, January-February 2012, Vol. 51, No. 1: 121–142.

Publisher – Google Scholar

83. Yüksel, M. 2012. “Cultural Sustainability, Branding and Reputation from Strategic Human Resource Management Perspective”,TProceedings of the 1st International Reputation Management Conference, Kadir Has University, Sept, Istanbul(www.slideshare.net; www.reputationinstitute.com).

84. Yüksel, M. & Kılıç, S. 2013. “Branding from Strategic Human Resource Management” A working paper, EIASM (European Institute for Advanced Studies in Management), 28th Workshop on Strategic Human Resources, Copenhag.