Introduction

The spreading of information everyday might be a vital issue in certain countries. People tend to rely on the latest information rather than filtering for trustworthiness. They do not understand the concept of information and at the same time failed to determine the relevancy. It became a challenge to concern what’s real and what’s fake. Different views from different levels of citizens to evaluate and interpret information sources, while adults have different views and effects compared to teenagers because of less experience. Information is different phenomena. These phenomena have been classified into three groups; firstly, anything perceived as potentially signifying something (e.g., printed books). Secondly, information is the process of informing someone else; and thirdly, information learned from some evidence or communication (Buckland, 2005). Besides, information is knowledge perceived. According to Smiraglia (2014), information is knowledge which is the things that are known, both equally (as in the knowledge base that defines a culture) and individually can be recorded in some tangible way. The records of knowledge can be organized to provide access both to the records themselves (as in a library) and to the knowledge they contain (as in information retrieval systems). Meanwhile, when the phenomena of excessive amounts of information happen, the growth of information overloads and information explosion occur. According to Allen & Shoard (2005), when the living systems are unable to process excessive amounts of information, it will lead to the phenomena of information overload and information explosion. Combined with the fact that technology can produce information much faster than people can process it, this means that people often find themselves unable to manage with an increasing volume of information.

Digital natives are those who live surrounded by technology. This generation born in or after the 1980’s has the culture of connectivity with the Internet, online creating and sharing (Prensky, 2001). Digital natives here consider heavy users, actively use social media and the Internet for the purpose of personal, professional needs, university requirements and so on. A “digital native” is a member of the younger generation who grew up in the cyber age. Although earlier studies have focused on digital natives’ competence in information technology (IT) usage, their vulnerability to IT addiction has received scant attention (Wang et al., 2019). The concept of ‘digital natives’ was first introduced by Prensky (2001) as a generation of people born in or after 1980. He defined digital natives as people who live their lives occupied in digital technologies and that they learn differently from previous generations of people (Ng, 2012). According to Prensky, digital natives have a culture of connectivity and online creating and sharing. The concept of digital natives refers to the generation that live into the technological age. This age consists of the Internet, video games and many other digital platforms (Murat & Sakir, 2020). The growth of technology, information and communication has such an enormous impact, making generational changes over time. Digital natives are a picture of the recent generation (Dyah Puspitasari Srirahayu, Dessy Harisanty & Esti Putri Anugrah 2021).

Social media are on how information is shared and integrated by the masses (Talwar et al., 2019). Social media enables users to communicate or interact with their peers by creating and sharing content, such as information, knowledge, news or else (Mills et al., 2019). By using the platforms of social media today, such as Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp, We Chat, and Instagram, they will lead people to communicate with each other and share information, news, knowledge and ideas, feelings, and emotions as well (Muhammad Anwar, & Tang, 2020).

Information sharing occurs when individuals convey information in any platform or acquire it from other sources. Nowadays, people tend to share various kinds of information, such as their status updates, experiences, comments, and advertisements on social media, such as Facebook and Twitter. The shared information has created many opportunities for businesses to gain economic values for both external and internal business decisions (Lin & Wang, 2020). Using the Internet for searching information and reading news can also have a profound impact on business, development, entertainment, education, and other areas (Ahler, 2006). The latest communication technologies such as the Internet have several common characteristics enabling the devices to perform alternative mass media functions when newer technologies empower the masses to seek the information they want and need (Breitrose, 1985). According to Kumar and Shah (2018), false information can be generated, shared and spread easily through the web and other social media platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, Twitter etc, resulting in widespread real-world impact. Information sharing is related to the activities of disseminating valuable information among people, systems or organizational units in an open environment (Roaimah, 2010). Information sharing should address the following issues; ‘what to share’, ‘with whom to share’, ‘how to share’, and ‘when to share’ of which if properly addressed would minimize sharing cost, information deficiency or overload and improve supply chain responsiveness (Sun, & Yen, 2005).

Intention is a key concept when it comes to understanding the reason for an individual’s action (Franco, Haase & Lautenschlager, 2010). The Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB), and The Theory of Reason Action (TRA) are used to relate with the intention in information sharing. These theories identify the importance of assessing the amount of control an individual has over behaviours and attitudes (perceived behavioural control). The components of the model consist of intention, attitude towards behaviour, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control. This model tries to point-out some elements such as attitude, subjective norms and behaviour that lead to individual intention. According to Lin & Wang (2020), The TRA, proposed by Fishbein and Ajzen (1975), implies a general theoretical model of behaviour that focuses on attitudes and social beliefs. In depth, the TRA is based on the proposition that an individual’s behaviour is determined by his or her intention to perform that behaviour. Attitude toward the behaviour is defined as “a person’s general feeling of favourableness or unfavourableness for that behaviour” (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980). Intention refers to the behaviours that lead people or indicate how hard people are willing to try and their efforts that they try to plan in order to carry out the behaviour (Ajzen, 1991; Liu, Li & Feng, 2011). The behaviour or decision-making intention of persons is determined by their attitudes, as a key antecedent of behaviour and behavioural intentions (Nikou, Mezei, & Brännback, 2018).

The Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA; Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975) and its extension and the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB; Ajzen, 1985, 1991) are cognitive theories that offer a conceptual framework for understanding human behaviour in specific contexts. In particular, the theory of planned behaviour has been widely used to assist in the prediction and explanation of several human behaviours. This study tries to explore the behavioural intention in sharing information among Gen Y or digital netizens by relating with The Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB), and The Theory of Reason Action (TRA), which is how the digital netizen plays a role and behaviour in the attitudes, subjective norms and perceived behavioural control in term of trying and interacting with social media. With the challenges posed by globalisation, technological and the explosive growth of information, there is a critical need for the latest information. The huge amount of information in social media leads to the phenomena of information overload and information explosion. The exposure to misinformation can trigger individuals’ additional information seeking to verify the information that they suspect to be false (Tandoc et al., 2017). For example, nearly 300 people have been killed by ingesting methanol based on harmful treatment recommendations that spread information across social media in Iran (Associated Press, 2020). The spreading and creating of false information or disinformation will put the society into risk , skew markets, and lead to the subverting democracy (Bastick, 2021). The objectives of this study are to identify digital natives’ regular basis used social media, and the level of digital natives by types of information intended to be shared on social media; secondly, to indicate the level of digital natives’ preferred and trusted sources to gain the information; and lastly, to determine the level of digital natives’ behavioural intention in sharing information on social media.

Methodology

A quantitative research method was adopted to address the research objectives in this study. To achieve the objective of this study, the quantitative method was applied, using a questionnaire as the instrument, which has been designed to investigate the nature of the study. Analysis was done by using IBM SPSS version 28.0.

Number of respondents

A total of 317 questionnaires were distributed to the Diploma Programme students at the Faculty of Information Management, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Rembau Campus. The response rate was 88.3% (280).

Results and Discussion

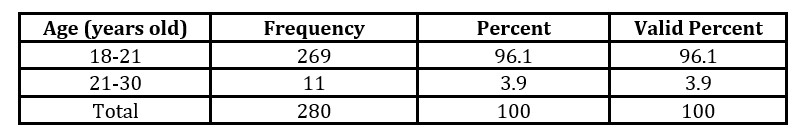

Distribution of respondents by age

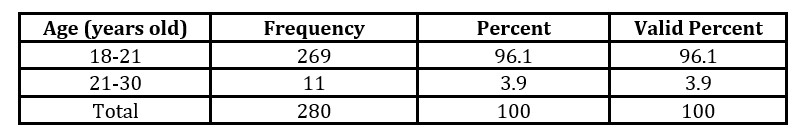

Table 1.0: Distribution of respondents by age

Table 1.0 shows that respondents, 18 to 20 years old, account for the largest proportion (269 or 96.1%) of the sample, followed by 11 (3.9%) of the respondents in the 21-30 age group.

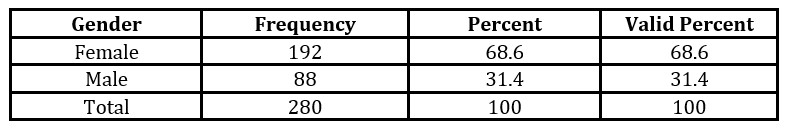

Distribution of respondents by gender

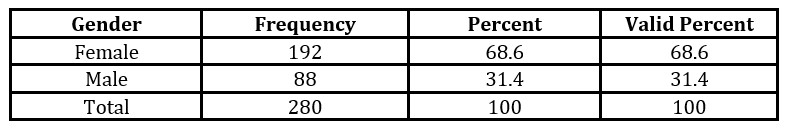

Table 2.0: Distribution of respondents by gender

Table 2.0 demonstrates 192 (68.6%) were female respondents, while 88 (31.4%) constituted male respondents.

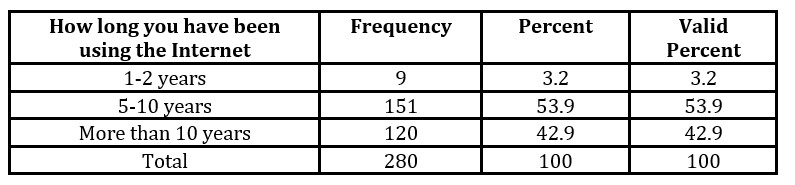

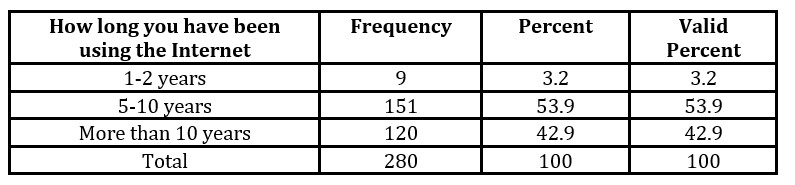

Distribution of respondents by years of using the Internet

Table 3.0: Distribution of respondents by years of using the Internet

Table 3.0 shows that respondents’ experience in between 1 to 2 years using the Internet (9 or 3.2%) of the sample, followed by 5 to 10 years using the Internet (151 or 53.9%) for the largest proportion of the respondents and lastly, more than 10 years using the Internet (120 or 42.9%) of the respondents.

RO1: to identify digital natives’ regular basis used social media, and the level of digital natives by types of information intended to be shared on social media

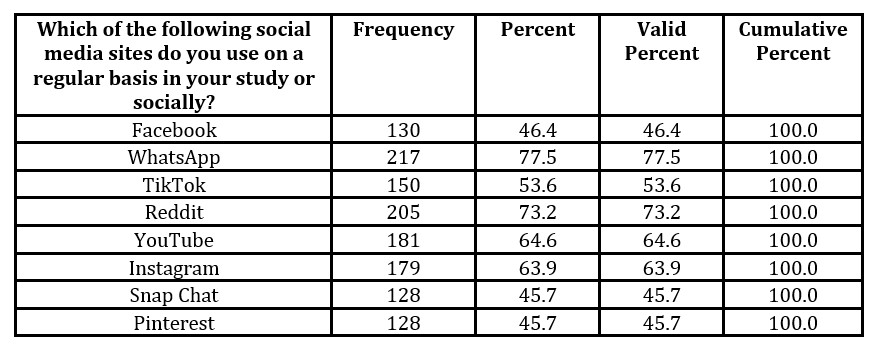

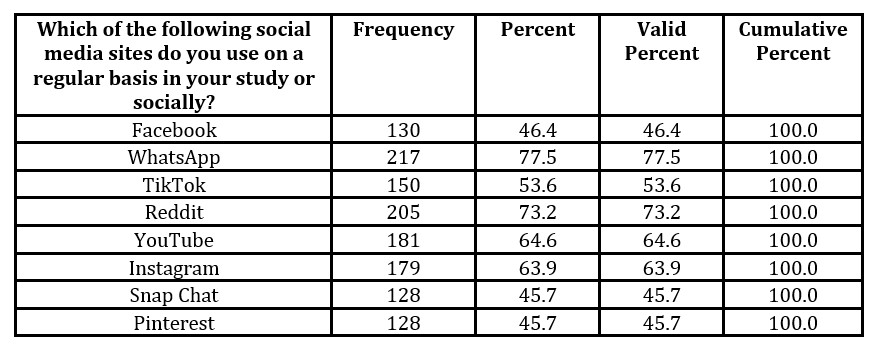

Respondents’ regular basis used social media

Table 4.0: Respondents’ regular basis used of social media

Table 4.0 shows that respondents’ regular basis used social media. It indicated few social media sites usage in study, socially or both, such as Facebook, YouTube, WhatsApp, Instagram, TikTok, Snapchat, Reddit, Pinterest, Twitter, and LinkedIn. From the results it reported that 77.5% of the respondents highly used WhatsApp for both study and social activities on a regular basis compared to other social media such as Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, TikTok, Snapchat, Reddit, Pinterest, Twitter, and LinkedIn. They actively used WhatsApp to communicate with the colleague and lecturer either related to the study purposes or having social interaction with other people, and at the same time, gather some information from that platform. Previous studies mentioned that people increasingly get their information from social media than from traditional news sources of information (Perrin, 2015) & (Shearer & Gottfried, 2017). Technologies such as the Internet offer the citizen the choice of spreading the information using various media such as WhatsApp, Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and any other Social Media Feeds.

Types of information intended to share on social media

Table 5.0: Types of information intended to do share on social media

In order to examine what type of information to share on social media, statements related to the respondents intention were evaluated in Table 5.0. The overall mean score of 3.12 indicates that respondents quite agree with the statement on frequently shared information on social media. Among the nine statements, the mean score is highest for sharing fun and entertainment information (mean=3.67) and lowest for sharing political information (mean=2.45). The overall mean scores on types of information to share on social media is 3.12. The phenomena of sharing information through social networking services are widespread and ubiquitous. Supported by Mutambik et al., (2022), various social media services exist, by which huge amounts of information are shared for purposes ranging from entertainment to professional development.

RO2: to indicate the level of digital natives’ preferred and trusted sources to gain the information

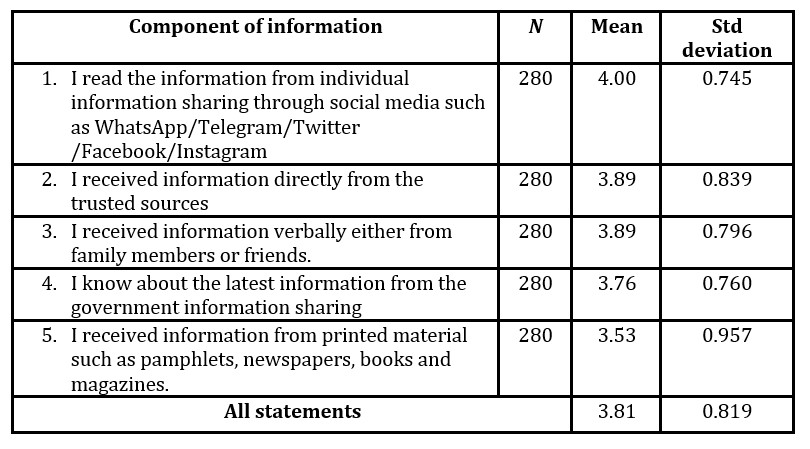

Level of respondent’s preferred and trusted sources to gain the information

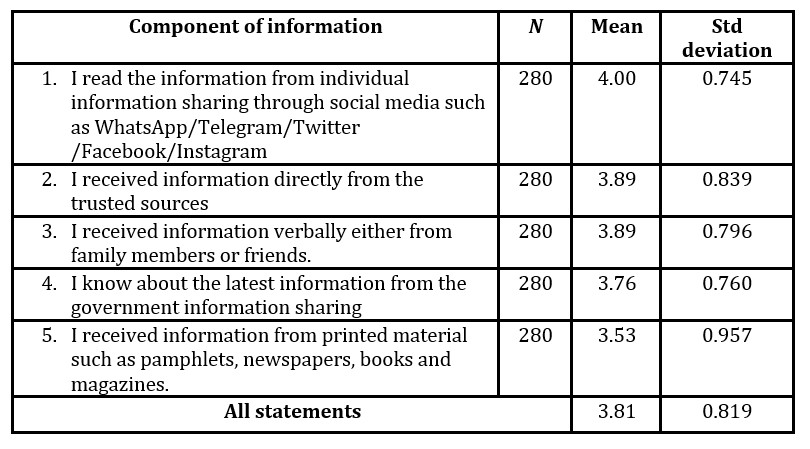

Table 6.0: Respondents’ preferred and trusted sources to gain the information

The summary statistics of respondents’ preferred and trusted sources to gain the information are given in Table 6.0. The overall mean score of 3.81 indicates that respondents quite agree with the statement on preferred and trusted media to gain the information. Among the five statements, the mean score is highest for I read the information from individual information sharing through social media such as WhatsApp/Telegram/Twitter /Facebook/Instagram (mean=4.00) and lowest for I received information from printed material such as pamphlets, newspapers, books, and magazines (mean=3.53). The overall mean score on preferred and trusted sources to gain the information is are 3.81. Social networks such as Facebook, WhatsApp, Twitter, YouTube, LinkedIn, Pinterest, and Instagram are the current platforms or communication channels for knowledge and information sharing, whereby the communities can deal and connect with family, friends, organizations and workplaces as well (Mutambik et al., 2022).

RO3: to determine the level of digital natives’ behavioural intention in sharing information on social media.

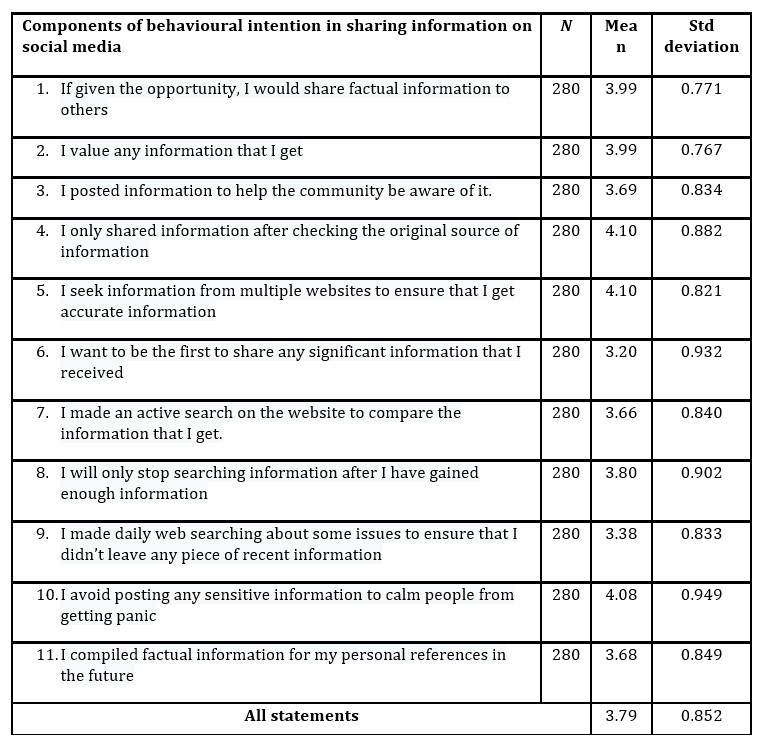

Level of respondents’ behavioural intention in sharing information on social media

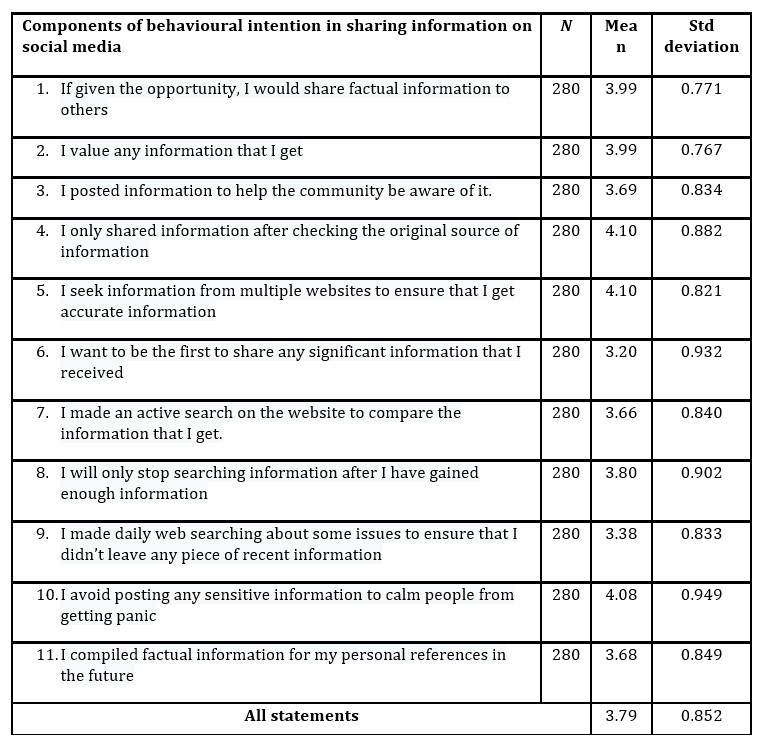

Table 7.0: Respondents’ behavioural intention in sharing information on social media

The summary statistics of respondents’ behavioural intention in sharing information on social media are given in Table 7.0. The overall mean score of 3.79 indicates that respondents quite agree with the statement on intention in sharing information on social media. Among the eleven statements, the mean score is highest for I only shared information after checking the original source of information and I seek information from multiple websites to ensure that I get accurate information (mean=4.10), and lowest for I want to be the first to share any significant information that I received (mean=3.20). The overall mean score on behavioural intention in sharing information on social media is 3.79. Supported by previous study, the respondents take an action to check and verify the information they received, then have the desire to share the information with their family members, friends by using social media (Suhaizal Hashim et al., 2020).

Conclusion

Findings showed that most of the respondents who are considered as digital natives actively used social media such as WhatsApp to gain and share information. They also used other platforms like Facebook, YouTube, WhatsApp, Instagram, TikTok, Snapchat, Reddit, Pinterest, Twitter, and LinkedIn for both social or study purposes. The respondents also have preferred sources to gain information before sharing it. They always get it from individual information sharing through social media such as WhatsApp/Telegram/Twitter /Facebook/Instagram and mostly sharing fun and entertainment information. They also have the intention while sharing the information through social media. They tend to share information after checking the original source of information and seek information from multiple websites to ensure that they can get accurate information before sharing or disseminating it. It can be concluded that they have the awareness of the impact of sharing disinformation from unreliable sources. The contribution of this study can give an idea to Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission (MCMC) to provide a guideline for the citizen before they post or share content on the Internet, especially social media platforms, to ensure that citizens are aware of what kind of relevant information is allowed. The awareness of communities regarding defamatory, derogatory, or inflammatory content of information, is suggested to explore the possibility for future study.

References

- Ahlers, D. (2006). News consumption and the new electronic media. Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics,11(1), 29-52.

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behaviour. Organizational Behaviour and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179-211.

- Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behaviour. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

- Allen, D. K., & Shoard, M. (2005). Spreading the load: Mobile information and communications technologies and their effect on information overload. Information Research, 10(2), 227. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1082034.pdf

- Associated Press. (2020). Coronavirus: In Iran, the false belief that toxic methanol fights Covid-19 kills hundreds [Press release]. South China Morning Post. https://www.scmp.com/news/world/middle-east/article/3077284/coronavirus-iranfalse-belief-toxic-methanol-fights-covid-19

- Bastick, Z. (2021). Would you notice if fake news changed your behavior? An experiment on the unconscious effects of disinformation. Computers in Human Behavior, 116, 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106633

- Breitrose, H. (1985). The new communications technologies and the new distribution of roles. Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing Corp.

- Buckland, M. (2005). What is the meaning of “data”, “information”, and “knowledge”? USA: University of California, Berkeley, USA.

- Dyah Puspitasari Srirahayu, Dessy Harisanty, & Esti Putri Anugrah. (2021). Causative factor of library usage among digital native. Journal of Library & Information Technology, 41(3), 199-205. https://doi.org/10.14429/djlit.41.3.16565

- Franco, M., Haase, H., & Lautenschlager, A. (2010). Students’ entrepreneurial intentions: An inter-regional comparison. Education + Training, 52(4), 260-275. https://doi.org/10.1108/00400911011050945

- Kumar, S., & Shah, N. (2018). False information on web and social media: A Survey. USA: Stanford University.

- Lin, & Wang. (2020). Examining gender differences in people’s information-sharing decisions on social networking sites. International Journal of Information Management, 50, 45-56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2019.05.004

- Liu, S. H., Li, P., & Feng, P. P. (2011, September). Mediation and Moderated Mediation in the Relationship among Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy, Entrepreneurial Intention, Entrepreneurial Attitude and Role Models. Paper presented at the 18th International Conference on Management Science & Engineering in Rome, Italy.

- Mills, A.J., Pitt, C., & Ferguson, S.L. (2019). The relationship between fake news and advertising. Journal of Advertising Research, 59(1), 3-8. https://doi.org/10.2501/jar-2019-007.

- Muhammad Anwar, & Tang, Z. (2020). What is the relationship between marketing of library sources and services and social media?: A literature review paper. Library Hi Tech News Number, 3, 1-5. https://doi.org/1108/LHTN-10-2019-0071

- Murat, S., & Şakir, G. (2020). The role of digital feedback on the self-esteem of digital natives. Türkiye İletişim Araştırmaları Dergisi, 35, 46-62. https://doi.org/17829/turcom.593767

- Mutambik, I., Lee, J., Almuqrin, A., Halboob, W., Omar T., & Floos, A. (2022) User concerns regarding information sharing on social networking sites: The user’s perspective in the context of national culture. PLoS ONE, 17(1), 1-27. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0263157

- Ng, W. (2012). Can we teach digital natives digital literacy? Computers & Education 59, 1065–1078. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2012.04.016

- Nikoua, S., Mezeib, J., & Brännbacka, M. (2018). Digital natives’ intention to interact with social media: Value systems and gender. Telematics and Informatics 35, 421–435. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2017.12.019

- Perrin, A. (2015). Social media usage. United States: Pew Research Centre.

- Prensky, M. (2001). Digital natives, digital Immigrants. On the Horizon, 9(5), 1-6. http://www.marcprensky.com/writing/prensky%20%20digital%20natives%20digital%20immigrants%20-%20part1.pdf.

- Roaimah Omar, Ramayah, T., May, C.L. , Tan, Y. S.,& Rusinah Siron. (2010). Information sharing, information quality and usage of Information sharing, information quality and usage of information technology (IT) tools in Malaysian organizations. African Journal of Business Management, 4(12), 2486-2499. http://www.academicjournals.org/AJBM

- Shearer, E., & Gottfried, J. (2017). News use across social media platforms. United States: Pew Research Centre.

- Smiraglia, R. (2014). Cultural synergy in information institutions. New York: Springer-Verlag.

- Suhaizal Hashim, Alias Masek, Nurhanim Saadah Abdullah, Aini Nazura Paimin, & Wan Hanim Nadrah Wan Muda. (2020). Students’ Intention to Share Information Via Social Media: A Case Study of Covid-19 Pandemic. Indonesian Journal of Science & Technology 5(2), 236-245. https://doi.org/10.17509/ijost.v5i2.24586

- Sun, S., Yen, J. (2005). Information supply chain: A unified framework for information-sharing. Intelligence and Security Informatics. ISI 2005. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 3495. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/11427995_38

- Talwar, S., Dhir, A., Kaur, P., Zafar, N., & Alrasheedy, M. (2019). Why do people share fake news? Associations between the dark side of social media use and fake news sharing behavior. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 51, 72-82, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.05.026.

- Tandoc, E. C., Ling, R., Westlund, O., Duffy, A., Goh, D., & Zheng Wei, L. (2017). Audiences’ acts of authentication in the age of fake news: A conceptual framework. New Media & Society, 20(8), 2745-2763. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817731756

- Wang, H.Y., Sigerson, L., Cheng, C. (2019). Digital nativity and information technology addiction: Age cohort versus individual difference approaches. Computers in Human Behavior, 90, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.08.031