Introduction

Entrepreneurship training programs have become an essential instrument to increase business activity in different countries (Fayolle, Gailly and Lassas-Clerc, 2006). Research to date supports the positive impact that these programs have on the creation of new businesses and recognizes their importance to promote socio-economic development (Douglas, 2013; Fitzsimmons & Douglas, 2011).

Entrepreneurship literature identifies several ways in which entrepreneurship education programs strengthen the entrepreneurial intent of participants. It is generally recognized that these programs benefit participants in terms of learning content, inspiration, and practice (Nabi et al. 2017; Ahmed et al 2020). In this sense, the Decido Emprender entrepreneurship program is designed in such a way that it allows participants to strengthen these three dimensions through the use of neurodidactic strategies. First, in relation to the benefits in learning, the program is composed of different modules, in which fundamental concepts are explained and activities are assigned in such a way that the participants learn how to carry out each task related to their entrepreneurship (e.g., the development of a business model), thereby allowing them to develop greater self-efficacy for their performance. Second, case studies of successful entrepreneurs are also presented during the program, and some are invited for participants to consider the positive aspects of entrepreneurship as a career path, as well as obstacles that they could encounter on the way to becoming entrepreneurs. This strategy seeks to strengthen the inspiration of the participants. Third, the program provides opportunities for participants to have formal and informal interaction with instructors and colleagues, and the program also allows for the creation of networks of entrepreneurs, where a supportive environment for the development of entrepreneurship is created. These networks of entrepreneurs allow participants’ attitudes towards becoming entrepreneurs to develop, as they can observe and experience what it is like to be an entrepreneur while encouraging and supporting each other.

Additionally, it is recognized that the impact of entrepreneurship training programs varies depending on the profiles of the participants and their environment (Lorz 2011; Ahmed et al 2020). In this sense, the Decido Emprender program makes it possible to consider characteristics of entrepreneurs, as well as their particularities and specific obstacles in the environment, as important elements in the entrepreneurial process. It is a novel program, since apart from encompassing the promotion of content benefits in learning, inspiration and practice, it strengthens the human-affective dimension and the formation of the human being through personal and family development, thus allowing the reduction of participants’ fears of failure in contexts that often affect people actions (Chams-Anturi et al., 2020). This is a key and differentiating factor of the training program presented, given that previous research suggests that participants in entrepreneurship programs are more inspired by pedagogical techniques that consider contextual barriers and inspiring activities that make it possible for them to become entrepreneurs, as opposed to imagining what it would be like to be entrepreneurs (Ahmed et al., 2020). This implies that a methodology that encourages the contrast of theory and reality within a training program favors understanding, and with it the most realistic possibility of putting what has been learned into operation.

Consequently, the Decido Emprender program has been designed to be broad in scope. In other words, it not only focuses on improving the entrepreneurial intention of the participants, but also seeks that they carry out entrepreneurial behaviors during the program. To accomplish this, participants receive seed capital and personalized (intensified) consultancies during the last stage of the program (Ovalles-Toledo et al., 2018). These consultancies allow them to understand and face the obstacles encountered when carrying out entrepreneurial actions related to the business opportunity developed, thus allowing for the measurement of the program’s direct impact on the participants’ creation of entrepreneurships.

Considering the aforementioned aspects in the design of the Decido Emprender program, the purpose of which is for migrants to systematically develop their business plan and start-up plan through seed capital, it was deemed relevant to understand the factors that explain entrepreneurial intention. This in addition to other relevant factors in the training process, such as the participants’ psychology, family, migration status and social integration; these factors can influence the choices and preferences of individuals at the time of undertaking.

Theoretical-Conceptual Context

In recent times, the world has been characterized by a great social compulsion. A migratory phenomenon has been developing on scales never before deployed, especially in Latin America and the Caribbean, as is the case of the high migratory transit of Venezuelans to other countries of the same region, whose statistics in the case of Colombia reflected a figure of 160,736 (one hundred sixty thousand seven hundred thirty-six) Venezuelans entering Barranquilla at the 30 January 2021 cutoff.

Beyond political causes, the economic consequences of this phenomenon with socio-emotional repercussions for both migrants and nationals require joint efforts in the host country that lead to support and collaboration initiatives for developing opportunities in the midst of adversity. Part of the challenges that must be faced, in addition to the search for employment and acceptance of these citizens in any field other than the profession or occupation that they had been carrying out in their own country, is the adaptation to new cultures and customs, sometimes seeing them as threatening in the middle of the adoption process. This merits the development of spaces where they can develop through trust in themselves, in others and above all, reflecting trust in others. Likewise, these spaces should prioritize respect through frank and friendly dialogue that contributes in preventing the host population from harboring feelings that manifest in xenophobia and aporophobia.

From this perspective, the importance of developing proposals and reconciliation projects between the parties involved is considered, especially those that aim to teach the migrant to function in the communities that welcome them, and recognize that inclusive and peaceful coexistence is possible.

To respond to this reality, the Decido Emprender program’s implementation is based on innovative methodologies, such as Neurodidactics, for the formation of migrant communities in socio-productive entrepreneurships with an emphasis on restoring human dignity. Its methodology corresponds to a comprehensive training with a curricular structure and a system’s approach. It contemplates social change and the inclusion of migrants, considering that economic empowerment originates from a planned behavior towards a specific objective, such as business creation and implementation, and entrepreneurial intention. Participants are intended to seriously consider entrepreneurship a life project that improves their self-esteem via the replacement of mendicity for productive, economic work in a country that welcomes them and offers them new opportunities.

Entrepreneurship Training

Studies on the impact entrepreneurship training has on entrepreneurial attitude, intentions, and behavior show mixed results (Ahmed et al., 2020). Some highlight positive results by recognizing the importance of the said factors in promoting socio-economic development (Douglas, 2013; Fitzsimmons & Douglas, 2011) and the capacities to detect business opportunities (Galloway & Brown, 2002 Peterman and Kennedy, 2003; DeTienne & Chandler, 2004).

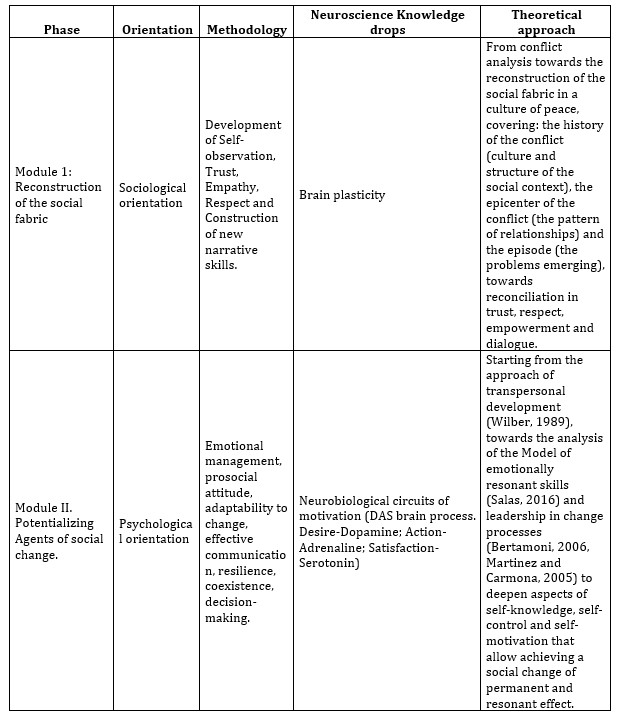

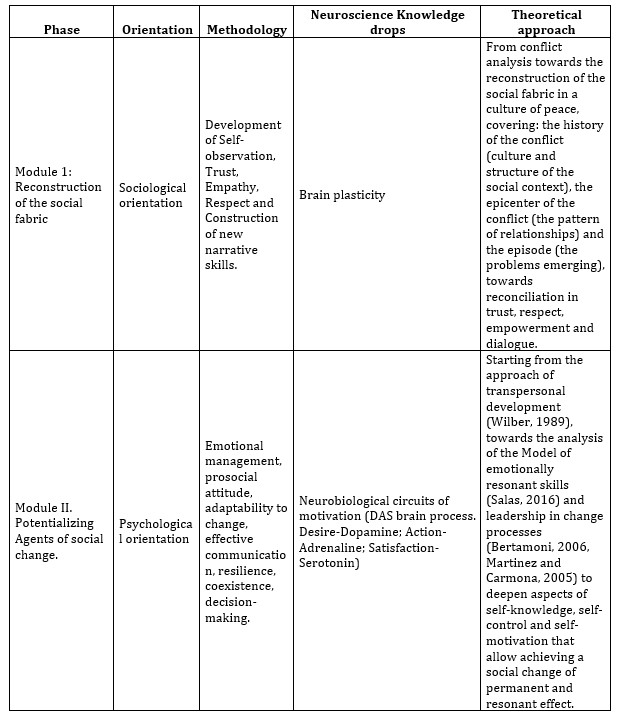

In this sense, those who have participated in entrepreneurship training programs are more likely to start their own businesses. However, other studies show another type of disappointing result, i.e., the abandonment of the idea of entrepreneurship (Mentoor and Friedrich, 2007; Oosterbeek, Van Praag and Ijsselstein, 2010). Hence the importance of planning a training program with a systemic approach that considers developing the dimension of being and doing, and that uses neurodidactic strategies for this purpose. The Structure of the Decido Emprender program is summarized in Table 1.

Each module contains classes planned under a disciplinary scheme of Neurodidactics based on the concrete contributions of neuroscience on the role that each type of brain represents in the learning process (emotional, cognitive, executive) through the equation: emotion + cognition = sustainable action. It is developed virtually with the help of the e-learning training model through the Blackboard platform in a theoretical-practical approach.

The training objectives scheme contemplates 1) Emotional beginning (I Decide to Be Methodology), 2) Drops of neuroscience knowledge dew (neurodidactic principle), 3) Theoretical-practical development of the class, and 4) Affective cognitive evaluative closure.

In order to analyze the implementation of the Decido Emprender program, the theory of planned behavior proposed by Ajzen (1988, 1991) is assumed, which considers how the perceived desirability and feasibility can be affected by precursors like education and experience. In the field of entrepreneurship, planned behavior theory has been used to understand how factors like attitude towards entrepreneurial behavior, perceived control of entrepreneurship and subjective norms are related to entrepreneurial intention. In addition, psychological and demographic factors like family, migration and social integration are also considered relevant in this program, since they can influence the choices and preferences of individuals (Dyer & Handler, 1994; Robinson, Stimpson, Huefner and Hunt, 1991). Conversely, learning to develop entrepreneurial skills and abilities cannot be understood as a process of knowledge acquisition. Rather, it must be understood as a complex and systemic process of permanent construction of meanings, as a consequence of the active participation of the subject in social contexts (Salas, 2016; Schultz W, 2015). Therefore, the Neurodidactic strategies for framing the migrant population in a context where they are exposed to new cultural and social practices that condition and shape their work, social, family and personal lives, deserves attention.

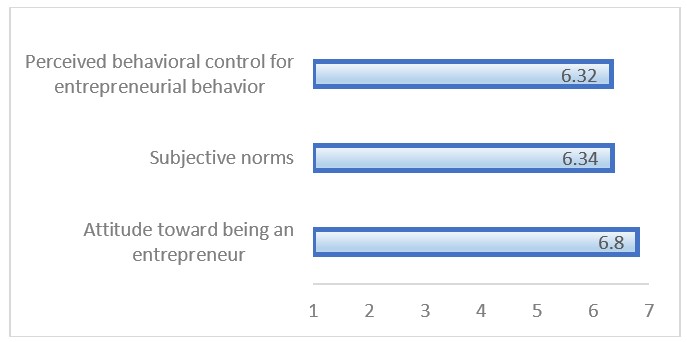

Table 1: Decido emprender program structure

Research Methodology

The methodology used in this study addressed the need to be able to analyze the findings that were obtained as it was developed. In this sense, the research was mixed, given it is the one that comes closest to achieving an integral account of the results obtained.

Apart from analyzing theories and assuming a position regarding the categories and variables, the study required building a new construct in the content of the entrepreneurship program that closes gaps by considering determining factors like family, migration and social integration. It also required developing a structured questionnaire, which favored an important leap in the way of conceiving entrepreneurship in conditions of vulnerability. The questionnaire was delivered to the participants in person during the last phase of the program. A total of 45 valid questionnaires were received, since 1 participant did not attend the event and 4 did not answer the questionnaire correctly (90% response rate).

Most items for the constructs studied were adapted from existing scales in the literature and were measured with a seven-point Likert scale (1 = “totally disagree”; 7 = “totally agree”). The attitude towards the entrepreneur was measured using items adapted from Linan and Chen (2009). The subjective norm items were adapted from Kolvereid (1996) and Ahmed et al. (2020). The elements of control of perceived behavior were adapted from Linan and Chen (2009). Entrepreneurial intent was adapted from Linan and Chen (2009) and Krueger et al. (2000). The business behavior items were adapted from Ahmed et al (2020) and Delmar and Lane (2003). The benefits of business education programs were measured using items developed by Souitaris et al. (2007). Finally, to measure migration, social integration and Neurodidactics, we developed items based on the content of the Decido Ser training program. In this sense, let us observe the results obtained.

Results

From the 45 responses, the following information was obtained:

- 42% of the respondents were between 20 and 29 years old, followed by 36% in the 30-39 age range. The average age is approximately 33 years.

- 80% of the respondents were female and 20% were male

- 69% of the respondents migrated to Colombia from 1 to 3 years ago. On average the respondents were more than 3.32 years in Colombia.

- 58% of the participants have a bachelor’s level of education, 20% professional, 15% elementary, 4% technologist, and 2% none.

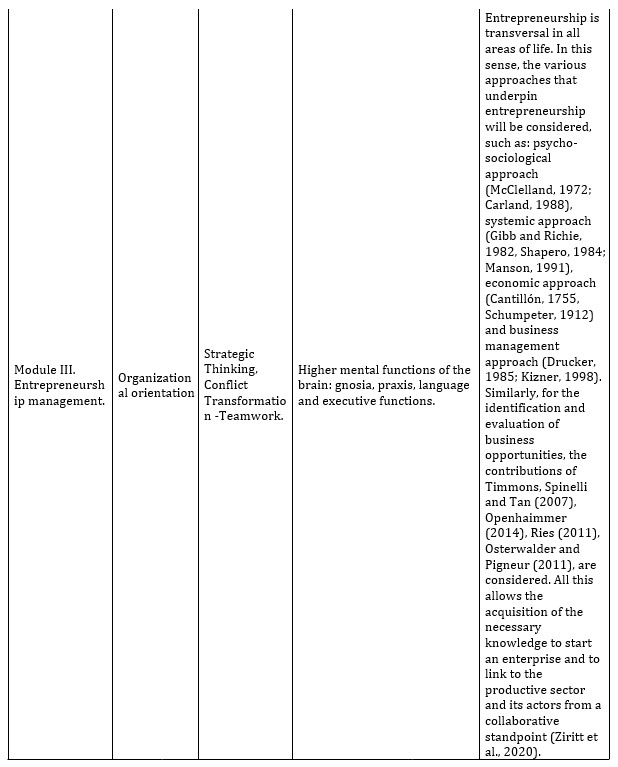

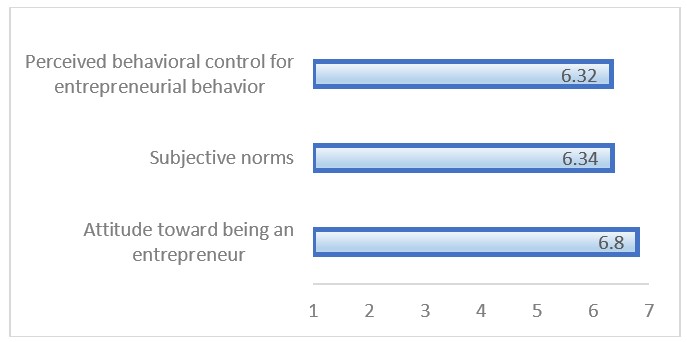

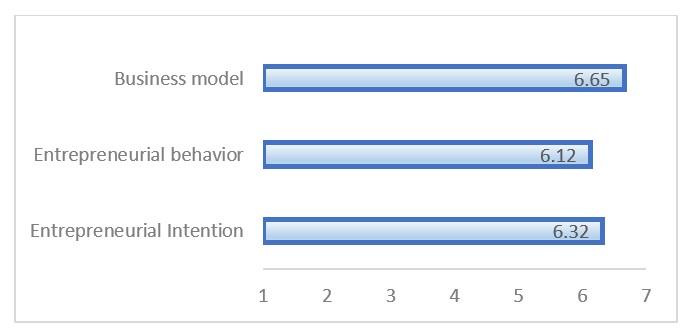

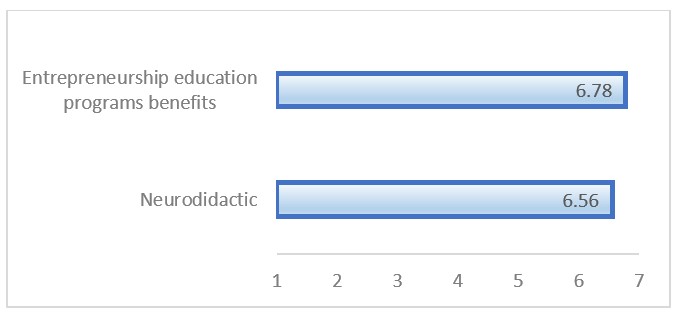

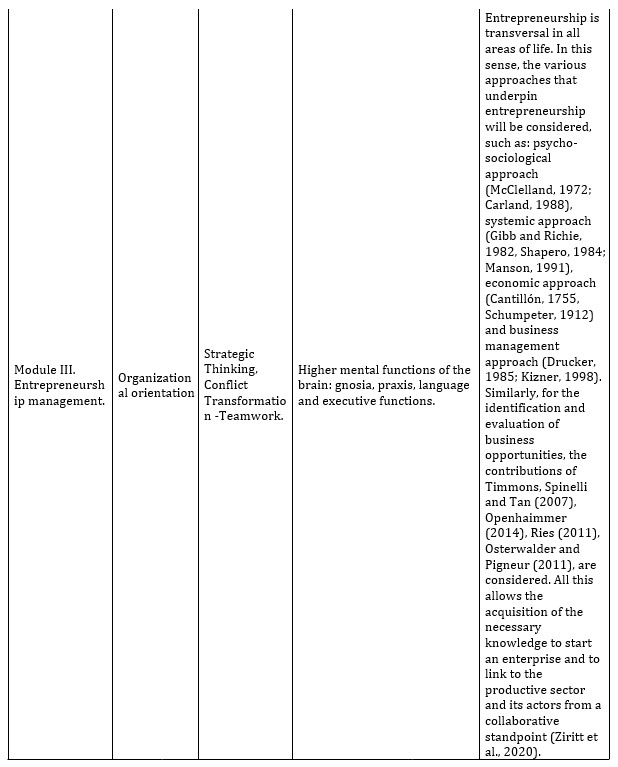

Below are the results obtained for each of the factors – role of the family (RF), migration process (MP), social integration (SI), attitude toward being an entrepreneur (EA), subjective norms (SN), perceived behavioral control for entrepreneurial behavior (PC), entrepreneurial intention (EI), entrepreneurial behavior (EB), neurodidactic (N), and benefits of entrepreneurship education programs (EPB).

Figure 1: General survey results

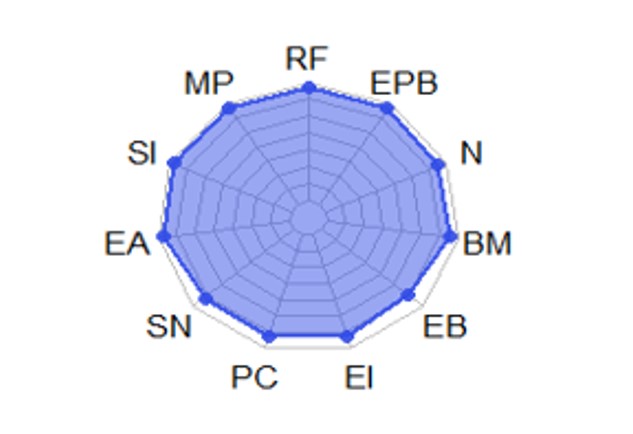

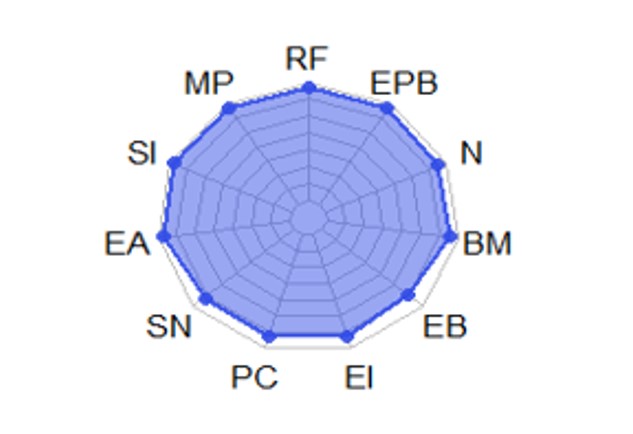

Factors related to the human-affective dimensions

Human-affective dimensions encompass factors like role of family, impact of migration and social integration. Role of family was measured by asking participants to indicate the degree to which they agreed with the following: (1) “I understand the importance of personal confidence and strengthening the family”, (2) “I understand the importance of having worked on the resignification of their life stories and the positive changes in the way they perceive themselves”, (3) “I understand and assimilate the new ways of responding to fear, moving from violence to healthier forms of expression of emotions, generating environments of respect, empathy and reconciliation”, and (4) “I understand the role that the family has to achieve a socio-productive enterprise and thereby improve my quality of life”. Migration process was measured by asking participants to indicate the degree to which they agreed with the following: (1) “I understand the concept of migration and its implications for their migration process and resilience”, (2) “I understand the stages of grief and contextualize them in my life”, (3) “I understand the concepts of self-esteem and self-concept, and have noticed the change in my behavior”, and (4) “I understand the role that the family has to achieve a socio-productive enterprise and thereby improve my quality of life”. Finally, Social integration was measured by asking participants to indicate the degree to which they agreed with the following: (1) “I understand the importance of recognizing my emotions and knowing how to handle them for resilience, coexistence and their integration into society”, (2) “I understand the concept and the importance of getting out of the comfort zone”, (3) “I understand that everything learned in this process has contributed to my visualization and design process of my own life project, and this has allowed me to link it with my business project”, and (4) “I understand that I am starting a new stage of life with goals and expectations”. The results show that the participants have a good level of understanding of the role of the family, the impact of migration and social integration.

Figure 2: Average of human affective dimensions.

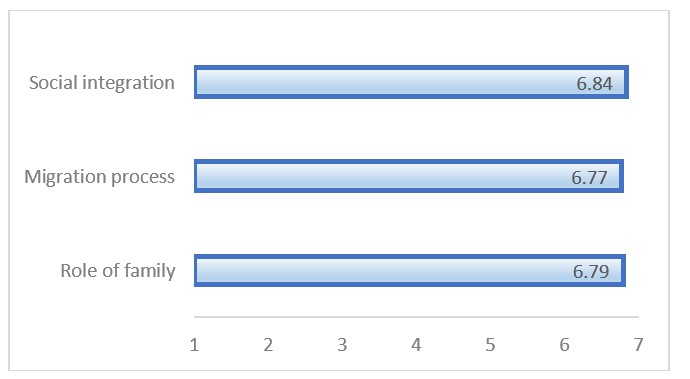

Factors related to entrepreneurial intention’s antecedents

Entrepreneurial intention’s antecedents involve elements like the attitude toward being an entrepreneur, subjective norms and perceived behavioral control for entrepreneurial behavior. Attitude toward being an entrepreneur was measured by asking participants to indicate the degree to which they agreed with the following: (1) “Being an entrepreneur implies more advantages than disadvantages”, (2) “A career as an entrepreneur is attractive to me”, (3) “If I had the opportunity and the resources, I would like to start a business”, (4) “Being an entrepreneur would give me great satisfaction”, and (5) “Among several options, I prefer to be an entrepreneur”. Subjective norms was measured by asking participants to indicate the degree to which they agreed with the following: (1) “It is important that my closest relatives think that I should start my own business”, (2) “It is important to me that my closest friends think that I should start my own business”, (3) “It is important to me that my colleagues in the entrepreneurship program think that I should start my own business”, and (4) “It is important to me that colleagues and people around me think that I should start my own business”. Finally, perceived behavioral control for entrepreneurial behavior was measured by asking participants to indicate the degree to which they agreed with the following: (1) Starting a business and keeping it running would be easy for me”, (2) “I am ready to start a viable business”, (3) “I can control the process of creating a new business”, (4) “I know the practical details necessary to start a business”,(5) “I know how to develop an entrepreneurial project”, and (6) “If I tried to start a business, I would have a high probability of being successful”. The program’s participants presented high levels in these variables.

Figure 3: Average of entrepreneurial intention antecedents.

Factors related to the realization of the entrepreneurship

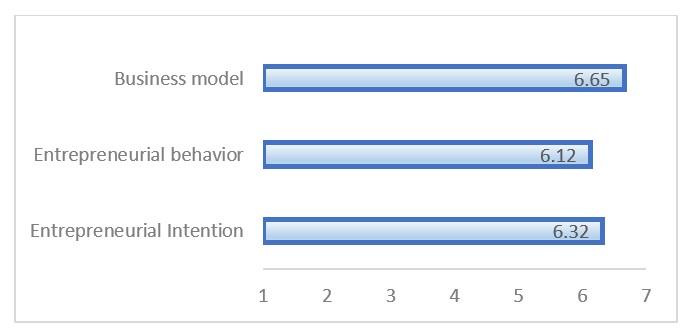

Realization of the entrepreneurship encompass factors like entrepreneurial intention, entrepreneurial behavior, and business model. Entrepreneurial intention was measured by asking participants to indicate the degree to which they agreed with the following: (1) “I am ready to do anything to be an entrepreneur”, (2) “My professional goal is to become an entrepreneur”, (3) “I will do my best to start and run my own business”, (4) “I am determined to start a company in the future”, and (5) “I have thought very seriously about starting a business”. Entrepreneurial behavior was measured by asking participants to indicate the degree to which they agreed with the following: (1) “To what extent have I been involved in preparing a business plan?”, (2) “To what extent have I organized a work team for the start-up of my business?”, (3) “To what extent have I adequate facilities or acquired equipment necessary for the start-up of my business?, (4) “To what extent have I developed the financial projections of my business?”, (5) “To what extent have I collected information about the market and the competition?”. Finally, business model was measured by asking participants to indicate the degree to which they agreed with the following: (1) “I can identify potential clients”, (2) “I can identify what customers value, (3) “I can identify channels to communicate with customers and provide solutions”, (4) “I can identify various ways to build customer relationships”, (5) “I can identify possible sources of income from the sale of products/services”, (6) “I can identify potential resources to create, deliver and capture value”, (7) “I can identify possible ways to create, deliver and capture value”, (8) “I can identify potential partners to do business with”, and (9) “I can identify the costs associated with doing business”. The results showed that the participants have a very good level in factors directly related to activities that allow them to better carry out their entrepreneurships.

Figure 4: Average of entrepreneurial realization factors.

Factors related to the perception of the participants about the entrepreneurship education program.

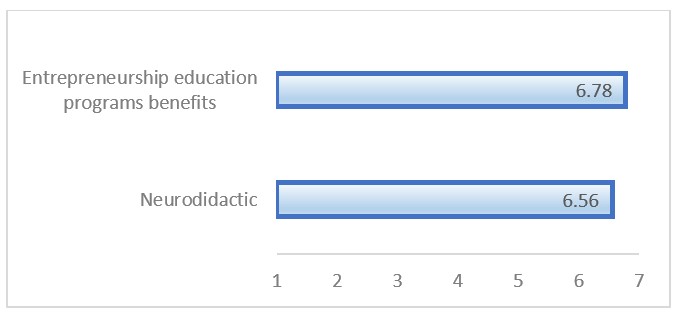

Participants perception about the entrepreneurship program involves elements like neurodidactic and entrepreneurship education program benefits. Neurodidactic was captured by asking participants to indicate the degree to which they agreed with the following: (1) “You were permanently motivated to learn”, (2) “You managed to put into practice each concept learned”, (3) “You felt affection in your learning process”, and (4) “You managed to link with colleagues for collaborative work”. Entrepreneurship education program benefits was measured by asking participants to indicate the degree to which they agreed with the following: (1) “The entrepreneurship program increased my understanding of the attitudes, values and motivation of entrepreneurs”, (2) “The entrepreneurship program increased my understanding of the actions someone must take to start a business”, (3) “The entrepreneurship program improved my practical management skills to start a business, (4) “A teacher’s opinions dramatically changed my “heart and mind,” and made me consider becoming an entrepreneur”, (5) “The opinions of an expert invited to classes drastically changed my “heart and mind,” and made me consider becoming an entrepreneur”, (6) “The opinions of my colleagues drastically changed my “heart and mind,” and made me consider becoming an entrepreneur”, (7) “The program allowed me to meet a group of classmates with an entrepreneurial mindset to form alliances and collaborative work”, (8) “The program provided me with seed capital to develop my business idea”, and (9) “The program allowed me to participate in the network of entrepreneurs (social networks) to visualize and market my products”. The results showed that the participants have very good perceptions of the program taken in entrepreneurship education.

Figure 5: Average of entrepreneurship program.

Conclusions

According to the information obtained in this study, the following conclusions can be drawn:

- The participants who attended the program presented diverse characteristics regarding their age, migration time and level of studies. This confirms that the entrepreneurship education program designed in this project adapts very well to the diversity of characteristics and conditions of the migrant population from Venezuela to Colombia.

- In relation to the perceptual variables of the research, it was observed the participants demonstrated very high levels. This confirms the positive results obtained during the execution of the entrepreneurship training program.

- The variables that stood out most in terms of how they managed each process developed during the implementation of the training program were: the assessment of the entrepreneurial intentions of the participants, their entrepreneurial spirits, their integration into a new society, and their positive perceptions of the suitability and usefulness of the training program in the program taken. In addition to demonstrating that the new construct formulated for this research, based on concepts like family, migration and social integration, shows that affect in the learning process, motivation and collaborative work are relevant factors for the formation of vulnerable migrant entrepreneurs. This provides new elements that allow us to explain reality when contemplating them, and helps in closing gaps in the construction of entrepreneurship programs.

Acknowledgement

This research was carried out with the support of the Program of Alliances for Reconciliation (PAR) of USAID and ACDIVOCA through the project Let’s adventure as a family: an experience of recognition, recovery, emotional reconciliation, and socio-productive entrepreneurship.

Bibliography

- Ahmed, T., Chandran, V. G. R., Klobas, J. E., Liñán, F., & Kokkalis, P. (2020). Entrepreneurship education programmes: How learning, inspiration and resources affect intentions for new venture creation in a developing economy. The International Journal of Management Education, 18(1), 100327.

- Ajzen, I. (1988). Attitudes, personality, and behaviour. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press.

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211.

- Bertamoni, J. (2006). Liderazgo participativo para equipos directivos. En M. Lomé (Ed.), Encuentro Entre Escuelas 2006. Buenos Aires: Fundación Compromiso.

- Cantillon, Richard (1755). Ensayo sobre la naturaleza del comercio en general, México-Buenos Aires, Fondo de Cultura Económica.

- Carland, J. (1988). “Who is an entrepreneur?” Is it a question worth asking? American Journal of Small Business, Volumen: 12 número: 4, página (s): 33-39

- Chams-Anturi, O., Gomez, A. P., Escorcia-Caballero, J. P., & Soto-Ferrari, M. (2020). Assessing organizational behavior: a case study in a colombian retail store. IBIMA Business Review.

- Delmar, F., & Shane, S. (2003). Does business planning facilitate the development of new ventures? Strategic management journal, 24(12), 1165-1185.

- DeTienne, D. R., & Chandler, G. N. (2004). Opportunity identification and its role in the entrepreneurial classroom: A pedagogical approach and empirical test. The Academy of management Learning and Education, 3(3), 242–257.

- Dyer, W. G., & Handler, W. (1994). Entrepreneurship and family business: Exploring the connections. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 19 71-71.

- Douglas, E. J. (2013). Reconstructing entrepreneurial intentions to identify predisposition for growth. Journal of Business Venturing, 28(5), 633–651.

- Drucker, P. (1985). La innovación y el empresario innovador.

La práctica y los principios. Editorial Edhasa. Barcelona: España

- Fitzsimmons, J. R., & Douglas, E. J. (2011). Interaction between feasibility and desirability in the formation of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, 26(4), 431–440.

- Galloway, L., & Brown, W. (2002). Entrepreneurship education at university: A driver in the creation of high growth firms? Education + Training, 44(8/9), 398–405.

- Gibb, A. y Ritchie, J. (1982). “Understanding the process of starting small businesses”, European Small Business Journal, 1(1), 26-46.

- Kirzner, Israel M. (1998). Competencia y Espíritu emprendedor, En: Knight, Frank (1921). Risk, uncertainty and profit. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co.

- Kolvereid, L., & Moen, Ø. (1997). Entrepreneurship among business graduates: Does a major in entrepreneurship make a difference? Journal of European Industrial Training, 21(4), 154–

- Krueger, Jr., Norris, F., Reilly, M. D., & Carsrud, A. L. (2000). Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, 15(5), 411–43

- Linan, F., & Chen, Y. W. 2009. Development and Cross-Cultural Application of aSpecific Instrument to Measure Entrepreneurial Intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(3): 593-617.

- Lorz, M., & Volery, T. (2011). The impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intention. University of St. Gallen.

- Mason, C. (1991), “Spatial variations in enterprise: The geography of new firm formation”. In Borrows, R. (ed.) Deciphering the enterprise culture: Entrepreneurship, petty capitalism and the restructuring of Britain”. Ch. 5: 74- 176. London: Routledge.

- Mentoor, E. R., & Friedrich, C. (2007). Is entrepreneurial education at South African universities successful? An empirical example. Industry and Higher Education, 21(3), 221–232.

- McClelland, D.C. (1972). What is the effect of achievement training in the schools? Teachers College Records 74:129-45

- Martínez, F. y Carmona, G. (2005). Aproximación al concepto de “Competencias Emprendedoras: Valor Social e Implicaciones Educativas. Revista REICE, 7 (3), pp. 82-98

- Nabi, G., Liñán, F., Fayolle, A., Krueger, N., & Walmsley, A. (2017). The impact of entrepreneurship education in higher education: A systematic review and research

The Academy of Management Learning and Education, 16(2), 277–299.

- Osterwalder, A. y Pigneur, Y., 2011. Generación de modelos de negocio. Editorial DEUSTO S.A

- Oosterbeek, H., Van Praag, M., & Ijsselstein, A. (2010). The impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurship skills and motivation. European Economic Review, 54(3), 442–454.

- Oppenheimer; A. (2014). Crear o morir. La esperanza de Latinoamérica y las cinco claves de la Innovación. Editorial Debate, Barcelona.

- Ovalles-Toledo, L. V., Freites, Z. M., Urbina, M. Á. O., & Guerra, H. S. (2018). Habilidades y capacidades del emprendimiento: un estudio bibliométrico. Revista Venezolana de Gerencia, 23(81), 217-234.

- Peterman, N. E., & Kennedy, J. (2003). Enterprise education: Influencing students’ perceptions of entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 28(2), 129–144.

- Ries, E. (2011). El método Lean Startup. Como crear empresas de éxito utilizando la innovación continua

- Robinson, P. B., Stimpson, D. V., Huefner, J. C., & Hunt, K. H. (1991). An attitude approach to the prediction of entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 15(4), 13–31.

- Salas de González, Mireya (2016). Modelo teórico gerencial de habilidades emocionalmente resonantes en el líder de organizaciones educativas. Fondo Editorial UNERMB. ISBN 978-980-6792-66-1. Cabimas, Zulia. Venezuela

- Shapero, A. 1984. The Entrepreneurial event in the environment for entrepreneurship. Lexington Books. Lexington, Mass.: Lexington Books

- Shumpeter, J. (1912). Teoría del desarrollo económico. Ciudad de México, México. Fondo de Cultura Económica.

- Souitaris, Vangelis, Zerbinati, Stefania, & Al-Laham, Andreas (2007). Do entrepreneurship programmes raise entrepreneurial intention of science and engineering students? The effect of learning, inspiration and resources. Journal of Business Venturing, 22(4), 566–591.

- Schultz W. (2015): “Neuronal reward and decision signals: from theories to data”. Physiological Reviews 95(3), 853-951.

- Timmons, J. A., Spinelli, S., & Tan, Y. (2007). New venture creation: Entrepreneurship for the 21st Century. 3: The entrepreneurial process. Págs 79-95.

- Wilber, Ken (1989). El proyecto Atman. Una visión transpersonal del desarrollo humano. España: Kairós

- Ziritt, G.; Moreno, Z.; Campechano, E (2020) .Actors network: Collaborative mechanisms for the development of sustainable alternative tourism in times of pandemic. Utopia y Praxis Latinoamericana; 25(Extra 8):321-336, 2020.