Introduction

The sector of young growth-oriented ventures typically struggles with lack of equity because their founders are only able to invest limited resources into their businesses. As such, they generally have to rely on external equity financing because they are yet to generate profits they could use to finance the company’s requirements. However, according to Leland/Pyle (1977), obtaining equity finance is extremely difficult, some of the reasons being a substantial information asymmetry between the capital provider and its recipient, difficult-to-predict development of the investee companies, and market risks.

According to Landström (2007) in advanced market economies, a lack of conventional sources of corporate financing is, in addition to the various forms of bank loans and state subsidies, covered by the use of formal and informal venture capital. Wright and Robbie (1998) defined formal (institutional) venture capital as professional investments of long-term, unquoted, risk equity finance in new firms where the primary reward is eventual capital gain supplemented by dividends. Mason and Harrison (1992, 1997, 2004) stated that ‘the institutional venture capital industry comprises full-time professionals who raise finance from pension funds, insurance companies, banks and other financial institutions to invest in entrepreneurial ventures’.

Venture capital (VC) is traditionally associated with the USA and the UK, from where private investment in various forms began spreading around the entire world. Just as in other Central and Eastern European countries, venture capital investment in the Czech Republic did not appear until after 1990 (Czech Venture Capital Association/CVCA 2010). Venture capital funds (representing formal venture capital) made investments worth €193 million in the Czech Republic in 2010 (Bundesverband Deutscher Kapitalbeteiligungsgesellschaften/BVK 2011). That is the equivalent of 0.13% relative to GDP (i.e. 42% of the EU average).

The CVCA (2010) stresses that legal barriers are an important reason behind the limited scope of resources available to domestic venture capital funds. According to CVCA, the relevant legal barriers prevent the establishment of a standard VC fund in the territory of the Czech Republic. A great number of VC funds operating in this country is thus domiciled in a different country and was incorporated in foreign jurisdictions.

Literature Review

Kaserer et al (2007), Achleitner and Fingerle (2003) and the AVCO study (2004) stress that if a policy is to stimulate the development of the VC market, then legal regulation of legal fund structures for VC investments and their tax treatment ought to be a priority. The VC market terminology also refers to legal regulation of fund structures. Fund structure represents the cornerstone of the VC market because it affects the exercise of ownership title, the manner and scope of investor liability, the method of profit and loss distribution, the manner and extent to which investors can participate in the management of the VC fund, the liquidity and inheritability of shares, and tax treatment at the levels of both the VC fund and the investors.

The existence of suitable domestic fund structures positively stimulates the development of the VC market, and ultimately the entire economy. In addition to direct effects, such as fundraising and investments, indirect effects also need to be stressed: the establishment and development of infrastructure required for the functioning of VC funds (fund management companies, administrators, depositaries, consultants). The provision of law usually consists of a set of individual legal norms regulating issues of fundraising, investment, portfolio building and tax treatment in the VC context (AVCO 2004).

Requirements Applicable to Legal Fund Structures for VC Investments

The AVCO study (2006), the EVCA study (2010), and further, Kaserer et al (2007), Horvath (2006), Dvořák/Procházka (1998) stress that the economic policy of the state ought to focus on the resolution of the following issues in particular as regards the optimization of fund structures: firstly, structuring of VC funds which is in harmony with the international provision of law for Limited Partnership as a legal form; secondly, tax transparency of the PE/VC fund structures; thirdly, recognition of VC fund structure as a specific form of the management company in order to avoid undesirable tax disadvantages for foreign investors; finally, no financial regulation for VC funds which approach institutional investors.

This paper addresses the following issues connected with the Czech formal venture capital market: How the current Czech legislation regulates the legal fund structures for VC investments? What is the tax treatment of VC funds and individual investors in the Czech Republic? What are the legal and tax regulations on the main European markets for VC? What are the key requirements for improvements of the current situation on the Czech VC market?

The paper is organized as follows. Immediately following this introductory section the data employed and the method of analysis are described. Next, the empirical findings are presented, and the paper closes with a discussion of the implications of the results for future survey.

Research Design and Methodology

The purpose of this study is to gain a greater understanding of the Czech venture capital market. Therefore, the nature of this study is explorative. It relies on primary and secondary data.

Primary data were collected asking members of Czech Venture Capital Association (CVCA). With CVCA Tax and Legislation Committee members was conducted a semi-structured interview to identify tax and legislation barriers concerning VC in the Czech Republic. An E-correspondence as well as several phone interviews were held on the basis of semi-structured interviews expressed the attitudes, knowledge and experience with this form of financing. Topics of the asked questions were: tax and legal factors affecting VC funds decision to enter a capital market, defining the tax and legal environment for limited partners and fund management companies, available VC fund structures within Europe, the tax and legal environment for VC in the Czech Republic, tax and legal barriers preventing the establishment of a standard VC fund in the Czech Republic, legislative amendments of corporate law.

Secondary data was obtained from studies published by the European Venture Capital Association/EVCA (2006, 2008, 2010), Czech Venture Capital Association/CVCA (2010), Austrian Private Equity and Venture Capital Organisation/AVCO (2004, 2006) and Kaserer et al (2007).

The data was processed using the content analysis method. The following discussion explains the data analysis results in order to draw some specific issues existing on the Czech venture capital market.

Results

The EVCA study (2008) assesses selected European countries with a view to their legislative and tax environment forLimited Partners and management companies. Six variables have been assessed on the scale of 1 (the best) to 3 (the worst): the existence of a dedicated or suitable domestic fund structure or investment vehicle for PE/VC investments, tax transparency of legal PE/VC fund structures for domestic Limited Partners, tax transparency of legal PE/VC fund structures for non-domestic Limited Partners, ability of non-domestic limited partners to avoid having a permanent establishment in the country, exemption of PE/VC fund management companies from VAT on management fees and freedom from undue restrictions on PE/VC funds on investment strategy and instruments.

The Czech Republic scored 1.67 on average in the “fund structures” category. It thus came below the European average in this category (EU25 score — 1.51). The composite score of the main European markets for venture capital such as United Kingdom, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Switzerland is above European average in this category. Interestingly, other main European markets such as Germany, Sweden and Italy also ranked below the European average, although their national markets are among the largest in Europe in terms of both fundraising and the volume of investment made.

Legal Fund Structures for VC Investments in the CR

Until 2006, the Czech Republic lacked an appropriate tax and legislative framework that would positively stimulate the establishment of VC funds. That is why a great majority of collective investment entities operating in the Czech Republic was established and pursues its business under laws of foreign jurisdictions. However, as of 2006, Act No. 189/2004 Sb., on Collective Investments, provides for the legal form of a qualified investors fund (“QIF”) which is a structure that can be used for the purposes of collective investment in the form of VC.

Topinka (2007) states that QUIFs may take on the legal form of an investment fund, open-end unit fund or closed-end unit fund. The investment fund is defined in Section 4 of Act No. 189/2004 Coll., on Collective investment, the unit fund in Section 6 of the same act. The distinction between an investment and unit fund is important because there are significant differences in their taxation.

Act No. 189/2004 Coll., on Collective Investment, defines the investment fund as a separate legal entity set up for the purpose of collective investment and licensed by the Czech National Bank to act as an investment fund. The on Collective Investment Act further stipulates another important condition: that investment funds can only exist in the form of joint stock companies. Therefore, unlike unit funds, investment funds have legal personality, and may use third parties for the pursuit of certain defined activities. This fact is of great important to the determination of corporate income tax base and the calculation of the resultant tax liabilities of the investment funds.

Pursuant to Act No. 189/2004 Coll., on Collective Investment, the unit fund is the aggregate of assets owned by all the unit holders within the fund pro rata to the unit holdings. The key factor in the tax treatment of unit funds is the fact that the unit fund is not a legal entity, i.e., that it lacks legal personality. Assets in the unit fund are managed by a regulated investment company (once again in the form of a joint stock company) that set the fund up, in its name and for the account of the unit holders, or shareholders.

Only qualified investors may invest into QIFs, such qualified investors being investor categories specifically listed in the act (e.g., banks, insurance companies, pension fund, and self-proclaimed experienced qualified investors). The QIF may be founded solely without a public offering, i.e., its shares (share certificates, as the case may be) are not an investment instrument intended for the general public.

The advantage QIFs offer as compared to other collective investment funds is that the law does not place any restrictions on QIFs in terms of investment strategy and investment instruments. QIFs are therefore not subject to inordinate restrictions in the investment area. Rules governing the fund’s activities are set out in its statute, and its foundation and commencement of business activities are subject to the grant of a license by the Czech National Bank. Where possible, the fund’s assets are in custody or other escrow provided by a depository bank that also may, under an agreement with the fund, monitor the fund’s activities more closely. Following the 2009 amendment to the Collective Investment Act, the original strict treatment of depositories was thus relaxed, and depositories are no longer obliged to monitor and check but only have assets in custody.

Tax Treatment of the Qualified Investor Fund (QIF)

QIF is attractive for investors thanks to the corporate income tax rate. Pursuant to the current wording of the Income Tax Act (Act No. 586/1992 Coll., on Income Tax), the base rate is 19% of the tax base; however, the rate applicable to investment funds is a mere 5% of the tax base (pursuant to Section 21 (2)(a) of the Income Tax Act). As in the case of investment funds, the income tax rate applicable to unit funds (as compared to regular legal entities) is lower, specifically, 5% of the tax base (Section 21 (2)(b)).

Pursuant to the Collective Investment Act, investment funds may only have the form of joint stock companies, and the calculation of their resultant tax liability is the same as for regular business entities that opted for the joint stock company as their legal form.

The conditions for the determination of the income tax base for investment companies forming unit funds are set forth in Section 20 (3) of the Income Tax Act. Pursuant to the Income Tax Act, an investment company forming one or several unit funds is obliged to determine separate tax bases for the investment company on the one hand and for the individual unit funds it created on the other hand.

According to Vlčková, Suchý, Å andera (2010), due to difficulties stemming from the application of certain tax law provisions, the practical utilization of QIFs in the form of unit funds is limited. There are two issues involved. First of all, there is the issue of tax depreciation of tangible assets. Pursuant to Section 28 (1) of the Income Tax Act, tangible assets may be depreciated for tax purposes by a tax payer with ownership title to such assets. The second issue is the provisioning for repairs of tangible assets. Pursuant to Section 24 (2)(i) of the Income Tax Act, the same is a tax-deductible cost (and thus reduces the income tax base). Pursuant to Section 7 of Act No. 593/1992 Coll., on Provisions for the Establishment of Income Tax Base, provisions for tangible assets repairs may be made by income tax payers with ownership title to such assets.

A problem arises in both above-described cases: the unit fund lacks legal personality, as such cannot own assets, cannot depreciate for tax, and further, cannot provision for repairs of tangible assets. The unit fund is owned neither by the unit fund itself nor the investment company managing the fund, but by the individual share certificate holders (or shareholders). The question thus remains who ought to claim tax depreciation of the unit fund’s assets, and who is entitled to provision for repairs of the unit fund’s tangible assets.

Withholding Tax on Shares in Profit Distributed at Investment Fund Level

The fund’s General Meeting (shareholders) decides on profit distribution. If the shareholders approve the distribution of dividends, the investment fund becomes obliged to pay withholding tax on the profit shares at the rate of 15% (Section 36 (2) (a) of the Income Tax Act). The investment fund may invoke an exemption from withholding tax provided that the terms and conditions set forth in Section 19 of the Income Tax Act are satisfied:

- The profit share is distributed by a subsidiaries who is a tax payer referred to in Section 17 (3), to the parent company,

- The investor is a trading company having the form of a joint stock company, limited liability company or cooperative,

- The investor is a tax resident of the Czech Republic or other EU member state,

- The investor has a minimum of 10% share in the registered capital of another company for a continuous period of 12 months.

Where it is possible to meet these conditions, the investment fund and its shareholders pay income tax at a rate equivalent to corporate income tax of the investment fund. QIF as an investment fund becomes a tax-transparent structure.

Withholding Tax on Profit Distributions at Unit Fund Level

In a unit fund, its shareholders decide on the distribution of profits generated. The investment company that founded and manages the fund is then obliged to pay withholding tax at the rate of 15% (Section 36 (2)(a) of the Income Tax Act). In the case of a unit fund, no exemption of profit distributions from withholding tax (pursuant to Section 19 of the Income Tax Act) exists because a unit fund lacks legal personality, and as such no relationship between a subsidiary and parent company can exist.

Permanent Establishment as a Condition

Investment by foreign investors through a QIF is not conditioned on a permanent establishment, i.e., foreign investors are not obliged to register in the Czech Republic, whereby they are not subject to certain other common obligations, either (e.g., the obligation to file tax returns).

Legal Fund Structures for VC Investments on the Main European Markets and Their Tax Treatment

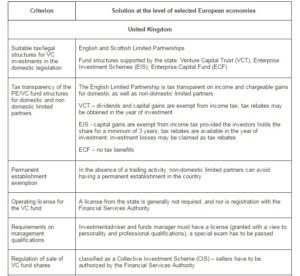

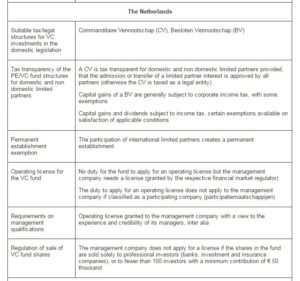

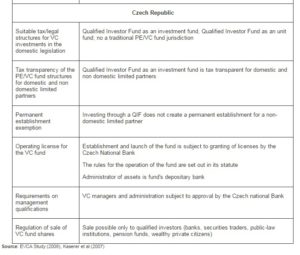

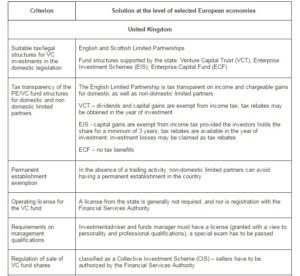

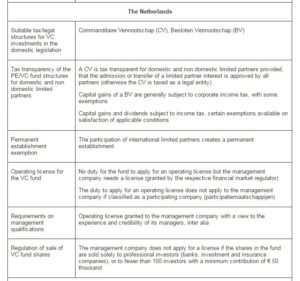

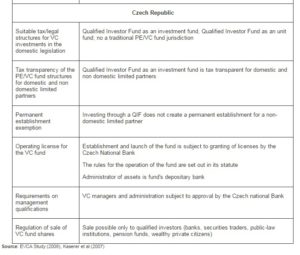

Tab. 1 shows, using Kaserer et al (2007) and EVCA Study (2008), a comparison of legal structures for VC investments in selected European countries (United Kingdom, Luxembourg, Netherlands and Switzerland). The comparison is based on the following criteria: the existence of a suitable legal structure for VC investments, its tax treatment, tax treatment of individual investors (Limited Partners), and regulation of the establishment and activities of the relevant legal structures, or management companies, as the case may be.

The comparison shows that VC funds are mainly structured as Limited Partnerships. Limited Partnership structures are founded by virtue of a Partnership Agreement that allows for a flexible regulation of any and all matters, such as management powers, profit and loss distribution, etc. The law does not stipulate a capital threshold for the LimitedPartnership in keeping with the “capital call and return on exit“ concept typically found in VC investments whereby capital is only accumulated in the fund when needed, and distributed to investors upon exit.

The legal form of Limited Partnership is a partnership, and as such a tax-transparent structure. Where a VC fund can be structured as a joint stock company (as is the case of the Luxembourg SICAR), the law provides for its quasi tax-transparency. This means that the VC fund’s gains are once again taxed at investor, rather than fund, level. This clearly shows that VC funds may be codified even in the form of joint stock companies.

If the LP has the status of “asset manager”, the investment is not associated with the creation of a permanent establishment from the perspective of foreign investors. The Netherlands is the only exception in this regards. Avoiding the establishment of a permanent establishment is an important aspect for VC fund investors when deciding where to invest: it is the only way of making sure that they would become tax payers where there tax domicile is. The specific tax treatment then depends on the investor’s domicile.

Differences can be observed in the licensing requirements applicable to VC funds in the countries under observation boasting developed VC markets. While in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands, licenses are not required by the bodies regulating financial markets, Luxembourg law stipulates substantial requirements (e.g., the fund has to be registered in a certain legal form, have an appropriate scope of business, minimum capital, has to file annual reports). However, certain minimum requirements on the quality of VC fund management, or management companies (reputability and qualifications of managers; in the UK, fund managers even have to pass a special exam) are defined in all the countries under review. The categories of sellers of VC fund shares and investors entitled to buy shares in VC funds (limited to qualified investors) are also regulated.

Discussion and Conclusion

It can be noted that as regards legislative conditions, the Czech Republic is not sufficiently competitive for VC market development as compared to other European countries. The missing provision of law for the internationally common legal form of Limited Partnership in domestic legislation in particular is a problem.

The only form of a QIF permissible in the Czech Republic, the joint stock company, is governed by the applicable provisions of the Commercial Code. QIF is a regulated joint stock company with a prescribed minimum capital (CZK 2 million given the fact that the QIF may be established solely without a public offering). Within a year of its establishment, the QIF must accumulate a minimum of CZK 50 million in capital; otherwise its license may be withdrawn by the Czech National Bank (CNB). The minimum capital requirement is not provided for by law in the case of the Limited Partnershiplegal form, which is better suited to the needs of VC investments.

To be able to commence its operation, the QIF has to obtain a license from the CNB. The regulator examines in particular the origin of the fund’s capital, business plan, suitability of the founders, and also the experience and qualifications of fund management. CNB is also interested in the fund’s statute, i.e., whether it meets statutory criteria and contains all the requisite information. The QIF’s assets are held in custody or otherwise in escrow by the depository bank. As noted above, countries with developed VC markets either do not apply any financial regulation, or only apply a “mild” form of regulation through the surveillance body along the lines of the “Directive on Alternative Investment Fund Managers“ (AIFMD).

QIF offers an advantage in that its statute may define the fund’s investment goals and policy (i.e., types of assets, risk diversification). In this regards, the QIF is a sufficiently flexible structure which fully conforms to the requirement that the investment activities of VC funds should not be restricted (the risk diversification issue). Potential restrictions in this area prevent a full utilization of the potential of investment opportunities, and are contrary to the nature of VC investments.

In the Limited Partnership context, there are active and passive investors. The General Partner is an active investor who manages the company and has an unlimited liability for its liabilities. The Limited Partners have no management authority and their liability is limited by their contributions. A QIF structured as a joint stock company does not permit the distinction between passive and active investors; nevertheless, it is possible to regulate mutual relations by way of shareholder agreements. A QIF in the form of a unit fund does allow for such a distinction.

A QIF can be established for a definite period of time or in perpetuity which is in keeping with international standards. Investors exit the QIF by selling their shares, or upon the distribution of their liquidation quota. The law does not define transferability of a share with respect to the LP structure but this can again be regulated by contract. In the QIF’s case, the fund is exited upon the dissolution and liquidation of the joint stock company. The dissolution and liquidation of the entity, followed by a subsequent distribution of asset sale proceeds, is generally the way also for Limited Partnershipsafter the agreed period lapses.

The legal form of the Limited Partnership is a partnership, and as such a tax-transparent structure. Tax transparency of the fund is a key criterion for VC investors because it ensures that taxation (in particular the taxation of revenues) does not take place at fund level but rather at the level of the investors (CVCA 2011). Unlike LPs, QIFs are subject to corporate income tax at a reduced rate (5%). However, if the investor is a trading company (with tax domicile in the Czech Republic or another EU member state), there is an option for distributions of profit from the investment fund to be exempt from income tax. The QIF in the form of an investment fund thus becomes a tax-transparent entity.

It can be noted that the main obstacles to the establishment of a standard VC fund in the Czech Republic consist in the inflexibility of corporate law (fixed capital requirement, non-existence of share classes, etc.), tax obstructions and non-transparency of the existing structures. Domestic legislation ought to respect the needs of the VC market, and introduce appropriate tax-transparent legal structures for VC investments either through the Act on Business Corporations (Act No. 90/2012 Coll.), or the Collective Investment Act. Otherwise the current situation will remain unchanged, whereby VC funds, as well as the management companies, as the case may be, mainly operate under foreign law, and “smart” equity financing can only be obtained outside the Czech Republic. The existence of adequate tax-transparent structures modelled on Luxembourg and the Netherlands would presumably positively stimulate the establishment of VC funds and management companies in the Czech Republic, and enhance the interest in investment into domestic companies (provided efficient investment opportunities exist).

Excessive regulation has to be avoided in connection with the establishment of a new legal structure. Achleitner and Fingerle (2003) and CVCA (2011) recommend that the law regulate only certain areas, such as the definition of the VC fund, its management and investment activities. A detailed regulation of the internal relations between the partners ought to be contained solely in the foundation documents. Excessive regulation does not make sense because investments in this category are reserved for qualified investors capable of protecting their rights and negotiating satisfactory conditions. Overly restrictive legal regulation imposes inappropriate restrictions on the ability of the investors and fund managers to regulate the structure of and relations within the fund in the partnership agreement and related contractual arrangements, at their discretion and using standard tools. The provision of law thus should not go above and beyond the above-referenced AIFMD.

However, the law ought to define minimum qualification requirements applicable to fund managers and management companies, as is the practice on advanced financial markets (issues of certification and further education). Obligatory authorization of persons selling shares in VC funds also ought to be introduced.

If the above recommendations inspired by European countries with developed legislation positively stimulating the VC market. in particular in terms of legal structures for VC investments, are successfully incorporated into domestic legislation, the Czech Republic will boast a modern investment tool required for a successful development of the VC market.

Table 1: Tax and Legal Environment for VC Investments on the Main European Markets – A Comparison

Acknowledgement

This paper was supported by grant FP-S-12-1 ‘Efficient Management of Enterprises with Regard to Development in Global Markets’ from the Internal Grant Agency at Brno University of Technology.

References

Achleitner, A. K. & Fingerle, C. H. (2003). “Venture Capital und Private Equity als Lösungsansatz für Eigenkapitaldefizite in der Wirtschaft — Einführende Überlegungen,” KfW-Stiftungslehrstuhl für Entrepreneurial Finance der Technischen Universität München, München.

Publisher – Google Scholar

BVK Special. Private Equity in Europa 2010 (2011). [online]. “Bundesverband Deutscher Kapitalbeteiligungsgesellschaften,” [June 7, 2012]. Available:

http://www.bvkap.de/privateequity.php/cat/154/title/BVK-Publikationen

Publisher

CVCA (2010). ‘Přehled Možných Investičních Struktur — Pracovní Materiál Pouze Pro Diskusní Účely,”’Prague.

CVCA (2010). “Private Equity and Venture Capital in the Czech Republic,” Prague, CVCA [Online], [Retrieved April 20, 2011]. Available: http://www.cvca.cz/images/cvca_UK-Ke-stazeni/4-file-File-CVCA_-_ADRESAR.pdf

Publisher

CVCA (2011). “Stanovisko The Czech Private Equity and Venture Capital Association,” (CVCA) k Návrhu Zákona o Investičních Společnostech a Investičních Fondech ze 14, května 2011, Prague.

Publisher

Dvořák, I. & Procházka, P. (1998). ‘Rizikový a Rozvojový Kapitál,’ Management Press, Prague.

Google Scholar

European Commission (2011). “Alternative Investments,” European Venture Capital Association. [Online], [Retrieved April 12, 2011]. Available: http://ec.europa.eu/internal_market/investment/alternative_investments_en.htm

Publisher

EVCA (2006). “Private Equity Fund Structures in Europe,” European Private Equity & Venture Capital Association. [Online], [Retrieved February 20, 2012]. Available: http://www.evca.eu/uploadedFiles/fund_structures.pdf

Publisher

EVCA (2008). “Benchmarking European and Legal Environments,“ European Private Equity & Venture Capital Association. [Online], [Retrieved March 20, 2012]. Available:

http://www.evca.eu/uploadedFiles/Executive_Summary_Benchmark_2008.pdf

Publisher

EVCA (2010). “Private Equity Fund Structures in Europe,” European Private Equity & Venture Capital Association. [Online], [Retrieved March 20, 2012]. Available:

http://www.evca.eu/uploadedfiles/home/public_and_regulatory_affairs/doc_sp_fundstructures.pdf

Publisher

EVCA (2011). “AIFM Directive,” European Venture Capital Association. [Online], [Retrieved April 20, 2011]. Available:http://www.evca.eu/publicandregulatoryaffairs/default.aspx?id=5574

Publisher

EVCA (2011). “Key Facts and Figures,” European Venture Capital Association. [Online], [Retrieved May 24, 2011]. Available: http://www.evca.eu/publicandregulatoryaffairs/default.aspx?id=86

Publisher

EVCA (2012). “Yearbook 2011,” European Private Equity & Venture Capital Association. [Online], [Retrieved February 26, 2012]. Available:

http://www.evca.eu/uploadedfiles/Home/Knowledge_Center/EVCA_Research/Statistics/Yearbook/Evca_Yearbook_2011.pdf

Publisher

Gloden, A., Jud, T. & Peneder, M. (2006). ‘Endbericht: Empirische Untersuchungen und Ergebnisse zur Wirkung von Private Equity und Venture Capital auf die Unternehmensentwicklung,’ Austrian Private Equity and Venture Capital Organisation, Wien.

Kaserer, C., Achleitner, A. K., von Einem, C. & Schiereck, D. (2007). “Private Equity in Deutschland,” Books on Demand GmbH, Nordestedt.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Landström, H. (2007). ‘Handbook of Survey on Venture Capital,’ Eward Elgar, Cheltenham, Northhampton.

Leland, H. E. & Pyle, D. H. (1977). “Informational Asymmetries, Financial Structure, and Financial Intermediation,”Journal of Finance, 32 (2), 371-387.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Mason, C. & Harrison, R. (1992). “The Supply of Equity Finance in the UK: A Strategy for Closing the Equity Gap,”Entrepreneurship and Regional Development 4 (4), 357-380.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Mason, C. M. & Harrison, R. T. (1997). “Business Angel Networks and the Development of the Informal Venture Capital Market in the U.K.: Is There Still a Role for the Public Sector?,” Small Business Economics 9 (2), 111—123.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Mason, C. M. & Harrison, R. T. (2004). “Improving Access to Early Stage Venture Capital in Regional Economies: A New Approach to Investment Readiness,” Local Economy 19(2), 159-173.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Paštiková, V. (2006). “Jak Zdanit Transparentní Entity,” [Online], [Retrieved February 14, 2011],http://ekonom.ihned.cz/c1-19631720-transparentni-entity

Publisher

Peneder, M., Schwarz, G. & Jud, T. (2004). ‘Endbericht: Der Einfluss von Private Equity (PE) und Venture Capital (VC) auf Wachstum und Innovationsleistung österreichischer Unternehmen,’ Austrian Private Equity and Venture Capital Organisation, Wien.

Robbie, W. & Mike, K. (1998). “Venture Capital and Private Equity: A Review and Synthesis,” Journal of Business Finance & Accounting 25(5) & (6), 521-570.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Rudolph, B. & Haagen, F. (2004). “Die Auswirkungen institutioneller Rahmenbedingungen auf die Venture Capital-Finanzierung in Deutschland,” [Online], [Retrieved May 24, 2010],

http://www.bwl.uni-muenchen.de/forschung/diskus_beitraege/workingpaper/3539.pdf

Publisher

Topinka, J. (2007). “Fondy Kvalifikovaných Investorů v ÄŒeské Republice,” [Online], [Retrieved May 24, 2010],http://www.epravo.cz/top/clanky/fondy-kvalifikovanych-investoru-v-ceske-republice-48837.html

Publisher

Vlčková, J., Suchý, P. & Å andera, M. (2010). “Některé Otázky Spojené s Fondy Kvalifikovaných Investorů,” [Online], [Retrieved May 28, 2011],

http://bankovnictvi.ihned.cz/c1-40099900-nektere-otazky-spojene-s-fondy-kvalifikovanych-investoru

Publisher

Act No. 189/2004 Coll., on Collective Investment.

Act No. 256/2004 Coll., on Business Activities on the Capital Market.

Act No. 586/1992 Coll., on Income Tax.

Act No. 593/1992 Coll., on Reserves.

Act No. 90/2012 Coll., on Business Corporations.