Introduction

Public sector institutions have strong links with civil society, in order to meet social needs, with the government in order to get its attention, budgets or different contracts, but also with the private sector to supply goods and services or to attract additional funds.

In fact, public sector financing is done both through income taxes and other fees paid by companies, as well as taxes on individuals’ income, while only a part of these payers are public services consumers. Also, public institutions may obtain an extra income by contracting loans, for which they must pay an interest rate. Moreover, the relationship between the public sector and companies of goods and services is bi-directional, as the state becomes their customer.

Public sector has also a relationship with workforce suppliers, in order to ensure the most important resources, but also with financial institutions, which can provide financial support in cases of deficit.

To maintain these links, it is important that public institutions to become generally known because of distinct skills, favorable image and services adapted to customer needs. In addition, in public companies, employees that are not motivated by an effective system of rewards, by a pleasant environment at work, or by providing advancement opportunities in higher professional positions are not interested to deliver public services at a high quality. Moreover, bureaucracy slows down progress in the public sector, leading to dissatisfaction of citizens, which are becoming more demanding, asking for services according to their expectances or according to the paid price (directly, or indirectly through taxes to the state).

Thus, by implementing marketing in its structures, public institutions will respond promptly and appropriately to external changes and diverse interests, their image will improve, the public employees’ satisfaction concerning their employment will increase and public services will become much better both in terms qualitatively and in terms of adaptability to customer needs.

Literature Review

Marketing is needed in public service organizations, because it leads not only to more efficient public services, but also to customer focused services (Mitchell, 2005). Marketing is also useful to public sector both in creating a loyal customer base and attracting new ones, and for positioning in a new market. Its benefits can be underlined when it comes about internal clients and partners and also in the pricing policy and the mix of services provided and promoted to existing and new clients (Day et al, 1998).

However, the concept of marketing can be seen as appropriate to the public sector, but in a modified form (Day et al, 1998), rather than a pale imitation of a private sector approach within the public service (Walsh, 1994). Even if public sector can learn the good practices from the private sector, the marketing cannot be transferred from one sector to another (Walsh, 1991). The concepts, frameworks and models need to be adapted to the specific operating environment of the public sector (Butler and Collins, 1995).

This approach is basing on five distinguishing characteristics of non-profit organizations, such as: (1) multiple, non-financial, conflicting, and ambiguous goals; (2) lack of agreement on means-ends; (3) environmental turbulence; (4) immeasurable outputs; and (5) effects of management intervention unknown (Hofstede, quoted in Kearsey and Varey, 1998, p.53).

Moreover, in order to analyze the applicability of marketing, then the specific character, conditions and tasks of the public sector need to be considered. These are summarized by Stewart and Ranson (1988) as follows:

– Private Sector Model:

– Individual choice in the market;

– Demand and price;

– Closure for private action;

– The equity of the market;

– The search for market satisfaction;

– Customer sovereignty;

– Competition as the instrument of the market;

– “Exit” as the stimulus.

– Public Sector Model:

– Collective choice in the polity;

– Need for resources;

– Openness for public action;

– The equity of need;

– The search for justice;

– Citizenship;

– Collective action as instrument of the polity;

– Voice as the condition (Stewart and Ranson, quoted in Walsh, 1991, p. 14).

Kotler and Lee (2007) considers that there are four categories of public activities, depending on the marketing applicability:

– Public enterprises in business sector, where marketing is applicable;

– Organizations that provide free services to users (such as: schools, police, firefighters) for which only the “price” would not be transferred from private marketing;

– Monetary transfer bodies (such as: social security, tax administration, customs), which are less concerned with marketing, even if the taxpayer can be considered more of a client;

– The intervention and control organizations (prison activities, judicial and regulatory) that would not be interested in marketing, unless we take into consideration the latest missions of social rehabilitation or guidance. (Kotler quoted in Matei, 2006, p. 370).

Governments and local administration began to realize the importance of implementing marketing within their activity. Local or governmental agencies develop marketing campaigns in order to attract investors in the privatization process, encouraging energy conservation and environmental protection, combating smoking and heavy drinking, and traffic legislation compliance (Cătană, 2003).

Research Methodology and Main Findings

Currently, due to high customer demands and fierce market competition, marketing has become indispensable in private enterprises and the public sector. Based on the above considerations, this research aims to identify the level of marketing development of public institutions in Romania.

Thus, we established the following objectives:

– Identify the percentage of public institutions, which have a marketing department;

– Identify the position of marketing department in the organizational structure of public institutions;

– Identify the criteria for organizing the marketing activities within marketing department;

– Identify the number of people working in the marketing department;

– Identify the main types of marketing activities in the marketing department;

– Identify the importance of marketing department in public institutions;

– Determine the percentage of public institutions, which run the process of market segmentation;

– Determine the market segmentation criteria used by public institutions;

– Identify the importance of market segmentation for the public institution;

– Identify the importance that public institutions attach to their own resources;

– Determine the respondents’ assessments regarding the institution’s resources;

– Identify the importance that public institutions attach to marketing environment;

– Determine the respondents’ assessments regarding the institution’s marketing environment;

– Determine the importance of customers’ opinions in establishing the products/services portfolio of the institution;

– Determine the respondents’ assessments regarding the adaptation of products/services of the public institutions to the market needs;

– Determine the respondents’ assessments regarding the relationship between public services’ prices and the institution’s global competitiveness.

The population is formed of Romanian public institutions, from the central and local administration, while the research unit is an employee within the management of the public body, or an employee within the marketing department (if this exists in the organization). The sampling method is a simple random one, and the sample includes 162 public institutions.

Regarding the results, nearly half (44%) of the institutions have a marketing department, although this is entitled “Marketing Direction” in 9% of cases, “Marketing Compartment” (12%), “Marketing Service” (15%) and in 18% cases “Marketing Office”. However, most respondents (28%) answered that the specific structure had a title distinct from those offered by the researcher in the questionnaire. Thus, the names are different, but most of them include the term “marketing”. Some examples are: “Marketing and Communication Direction”, “Marketing and Public Relations Direction”, “Division of Public Relations, Marketing and Projects”, or “Marketing – Taxpayers Relations”.

Most of the institutions (52%) have the Marketing Department on the same level as other departments. Only in 16% cases, the Marketing Department is subordinated to other departments.

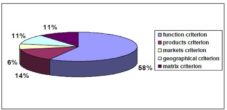

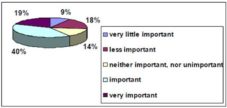

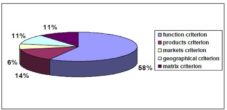

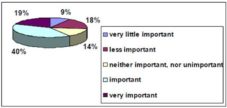

Fig.1. Marketing Departments’ Organizing Criteria

The function criterion is used in over 50% of institutions that have a marketing department, in order to organize the marketing activities. The rarest used criterion is the “markets” one. This probably stems from the lack of a comprehensive profile of the consumer, due to the absence of market segmentation on one hand and the general perception that public services are for all citizens or taxpayers, on the other hand.

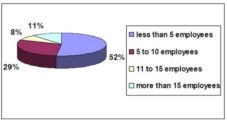

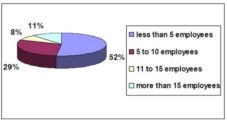

In half of the institutions that have a marketing department, are working less than 5 employees, while entities with more than 15 marketing employees hold a share of 11%.

Fig.2. Number of Employees within Marketing Department

Marketing Activities within Romanian Public Institutions

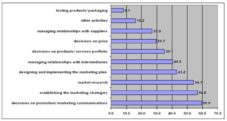

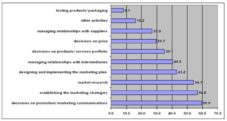

As shown in Figure no. 3, within the marketing departments of Romanian institutions, the decisions regarding the promotion of public services dominate. This is consistent with some of the marketing structures’ names mentioned by the respondents.

Fig.3. Main Activities within Marketing Department

Other specific marketing tasks of public institutions are: establishing the marketing strategies (56.8%), market research (54.1%) and designing and implementing the marketing plan (43.2%).

As public institutions offer consists mainly of services, and rarely tangible goods, it is understandable why the products testing and packaging occupy last place in the list of marketing activities undertaken.

Also, decisions on offer price are not among the most important responsibilities of marketing staff, as most public services are provided apparently free of charge, but actually it is charged a prepayment through taxpayers’ contributions to the state budget.

Other activities that are taking place in the marketing departments of Romanian public institutions are: drawing up contracts with customers; revenue collection, budget consolidation; drafting documents to inform businesses and individuals.

Other answers for open-ended questions on marketing responsibilities have been “sponsoring”, “promoting services” and “managing the relationship with mass-media”, which highlights a rather poor training of the respondents in marketing domain, since they have not checked the “decisions on promotion / marketing communications”.

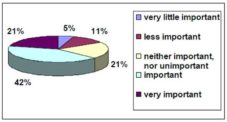

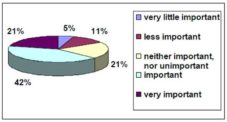

Although only 44% of institutions have a marketing department, the percentages of those who think that its presence in the institution is important have a high value (42% – “important” and 21% – “very important”). Only 5% of respondents said that marketing department is of very little importance.

Fig.4. Marketing Department’s Importance within Public Institutions

Market Segmentation

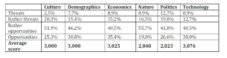

Less than half of public institutions analyzed (40%) go through the process of market segmentation, the most frequently used criteria being the economic (62.5%) and demographic ones (43.8%). Purchasing and consumption behavior are criteria used for segmentation in only 12.5% of cases, while the psychographic criteria are relevant in 15.6% cases.

In accordance with the answers given to question about the importance of specific marketing structure, are the respondents’ opinions about the importance of segmentation process. Therefore, the average score’s value (3.416), in this case, is not too high; it easily exceeds the middle level.

Fig.5. Importance of Market Segmentation

Marketing Environment of Public Institutions

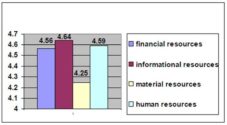

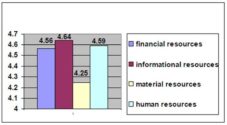

The following figure shows the importance of resources for public institutions in Romania. The average scores of financial, informational, material and human resources are in this order: 4.556, 4.642, 4.247, 4.588. Most respondents believe that all resources of public organizations are very important, and of these, on the first place, according to the average score, are the informational resources, and on the last place – material resources.

Fig.6. Resources’ Importance

However, it is known that the efficiency of public services in the administration is determined by both its financial and material resources, and especially by its human potential. Therefore, human resources ranks second in the ranking, according to the average score. An administrative system equipped with sufficient material and financial means, with necessary administrative law, cannot perform its functions without professionally well-trained civil servants and managers.

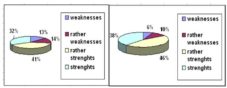

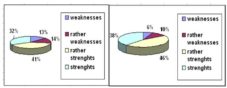

As a representative of the public enterprise, the public employee acts as a link between customers and the public service bodies. Most of the respondents declared that financial resources are relative strengths (41%) or significant strengths (32%).

Fig.7. Financial (Left) and Informational (Right) Resources’ Assessment

Although public institutions’ image, perceived by citizens, is unfavorable in terms of financial resources amount, the research results have shown that these organizations do not face great difficulties in this regard.

In the evaluation of informational resources, it was found that almost half the sample considered that they are relative strengths (46%) and only 6% say they are significant weaknesses.

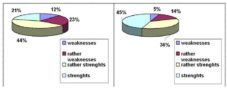

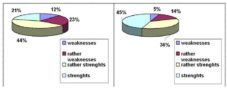

Public institutions do not enjoy a favorable situation in terms of material resources, fact that is proven by the respondents’ answers. Twelve percents of the total sample stated that these resources fall within the significant weaknesses and only 21% believe they are significant strengths.

Fig.8 — Material (Left) and Human (Right) Resources’ Assessment

Human resources are the most appreciated in public organizations, 81% believing that they are relative strengths (36%) or significant strengths (45%), as opposed to 19 percent, which evaluates public sector staff as a relative weakness (14%), or significant weakness (5%).

In conclusion, in a ranking based on the resources assessment, the human ones hold the first place with an average score of 3.205, followed by informational and financial resources, with average values of 3.150, 2.924 respectively. The last place is occupied by the material ones, which obtained a score below the average (2.744).

The most important elements of marketing microenvironment are – according to the respondents – customers or the public. This is justified by the fact that although not all Romanian citizens enjoy all the public services, they pay for them by state taxes, thereby contributing to the formation of the national budget. It is therefore more than necessary to know those payers that are not receiving various public services and to monitor their attitude towards public bodies.

Fig.9. The Importance of Micro and Macro Environment

The slightly decreased importance of competition can result from the public institutions’ monopoly situation on the market and the inability of private companies to match state bodies on diverse portfolio of services and greater delivery capability.

Political marketing environment strongly influences the activity of public institutions, so that a relatively high percentage of the respondents (54.3%) consider that this element of the macro is very important. However, the average score achieved by political environment is less than the average score for the economic environment.

In last place in the ranking drawn up according to macro-environment importance, is situated the natural environment, whose score is surpassed by similar values of cultural, demographic and technological factors.

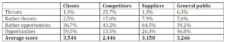

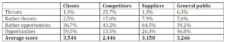

Table 1 shows the average score obtained by the four components of the microenvironment: the general public, suppliers, competitors and customers, according to their influence on the general activity of the public organization, and indicates the percentages in the sample according to their responses on the above aspect.

Table 1: Micro-environment’s Influence on Public Organization’s General Activity

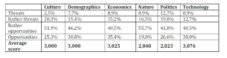

Regarding the macro-environment, the respondents consider that influence of the political environment is similar to the influence of technological environment. First of all, the political factor influences the public sector in a largely measure, as all decisions taken at central government or ministries have a direct impact on the economy of a state. Over recent years, the trend of globalization has been growing stronger, along with the dynamic development of social systems, which gives public companies in Romania the possibility to adapt to market requirements and to adopt measures that proved effective in other states. Any intervention in the public sector involves changes in major components, including central government, local government and other public services.

Second of all, the influence of technological environment should not be neglected, as researching the consumers’ needs, public organizations realize that people want to benefit from faster and more comfortable transport, from heat, gas and electricity distributed in maximum safety conditions, from water and sewer, or sanitary facilities and locations. However, all this requires certain and advanced infrastructure or technology, to which both the State and municipal service providers must show an interest. In last place in the ranking, lies the demographic environment, whose score is exceeded by the value of economic environment. Table 2 indicates the percentages in the sample according to their responses on the above aspect.

Table 2 – Macro-Environment’s Influence on Public Organization’s General Activity

Customers’ Importance

The largest share of the sample (81%) believes that customers’ opinions on public institutions’ products and services portfolio are important (36%) and very important (45%). Only 11% do not consider them important, or unimportant, while the rest of the sample thinks that clients’ opinions are not important in the process of adopting marketing decisions. Calculated score is slightly more than four (i.e. 4.163), which stresses the idea mentioned above.

Also, the respondents are confident when it comes to adapting their products or services to market requirements. In this case, the average score reflects the fact that the vast majority of respondents (84%) consider that they offer customers what they really want (31% – in a very large measure; 53% – in a large measure).

It should be noted however, that no respondent has considered the option that public services are less or very little adapted to market needs. This may be based on a real high degree of satisfaction of public services consumers or lack of marketing research, in this case the respondents’ opinions being purely subjective.

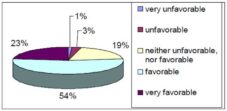

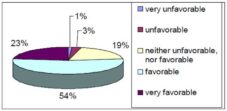

Although respondents’ appreciation on the relationship between services’ prices and public institutions’ global competitiveness is subjective, the calculated average score is not very high. It can be said, however, based on responses collected, that this report tends to be favorable.

Fig.10. Relationship between Public Services’ Prices and Organization’s Global Competitiveness

Conclusions

In Romania, public institutions implement specific marketing concepts, but not continuously and efficiently. Although they see the utility of marketing implementation, this objective is treated superficially, as demonstrated by the absence of marketing structures in more than half of the institutions, poorly trained staff, and limited financial resources allocated to marketing activities.

In other countries, there are similar or different impediments related to marketing implementation within public administration, as: the distribution costs or limited public finances, very strict financial rules regarding the advertising in this field, and the shortcoming of limiting marketing to its communication function. Moreover, an international qualitative marketing research show that various public administration officials consider that Marketing is useful when the public institutions need to inform the citizens about their services, or when the consumer are unsatisfied with the political decisions. In addition, Marketing may be a solution for a new approach of public services delivery, opposite to a controlled one. (Kaplan, Haenlein, 2009)

The previous ideas coincide with Graham’s opinion, which argues that the quite different environment and purpose of most of the public sector make the application of marketing at least difficult if not entirely inappropriate (Graham, 1994).

The public institutions attach great importance to customers and general public and minor importance to competitors. The respondents’ assessments regarding the macro-marketing environment are mostly favorable, except political factor, which may unfavorably affect the activity of public organizations. According to respondents’ answers, the offer is adapted to market needs, as the importance of customers’ opinions in establishing public services is high.

The respondents’ answers mentioned in the paragraph above have a correspondent in the specialty literature, as there are highlighted some variables or conditions that substantially modify the development of marketing practices in the public sector. Such factors include even more elements than the specified ones within the quantitative research: (1) the nature of the products involved, (2) differences in policy/ marketing objectives, (3) the monopoly position of government, (4) constraints on the marketing mix, (5) the visibility and accountability of government, (6) the nature of the policy formulation, administrative and evaluative processes, (7) a skepticism concerning the reputation of marketing. (Ritchie, LaBrèque, 1975)

The increased importance of customers in the public sector has been also underlined in the specialty literature, for over 30 years. Some authors suggest four specific steps in the development of public policy: using the consumer research, performing the cost/benefit analyses of proposed policies, testing the market proposed policies and evaluating the policies that have been put into effect. They consider that these marketing measures implemented in the public sector would lead to an improvement of public policy development and implementation of laws, rules, regulations or programs (Enis, Kangun & Mokwa, 1978).

Even if the marketing implementation in the analyzed institutions is poor, the respondents see that the successful application of marketing in this sector can lead to:

– Market Orientation

Thus, public enterprises can adapt to the realities of Romanian economy and society, while addressing the similar structures of the European Union and other developed countries.

– Achieving Marketing Goals

It will seek to increase efficiency of organizations, on medium and long term, which will result in strengthening their strategic skills, reducing government spending and adapting the public services to the needs and preferences of customers / citizens.

– Involvement of All Resources to Identify both Favorable and Unfavorable Trends on the Market

Public enterprises develop their ability to react promptly and appropriately to external changes and diverse interests.

– Improved Image

The relations between public enterprises and citizens will change, by strengthening and widening of the participation of civil society in decision-making process, by ensuring transparency in public acts and processes, but also through operative communication with citizens.

– Increased Satisfaction of Public Employees on their Job

There will be a focus on the civil servant career with the appropriate salary, incentives and ensuring normal working conditions in order to respect the principle of stability and continuity at work.

– Improved Communication both Horizontally and Vertically (within public bodies, and between them and the subordinated units)

It will streamline the relationship between central and local government, between public authorities and the common county, cities and municipalities and even creating an integrated information system.

– Improved Quality of Public Services

It will eliminate bureaucracy by streamlining administrative procedures and the introduction of equipment and technology.

The major aim of marketing implementation in public services domain is to create organisms able to carry out their functions so as to prepare the conditions and to ensure economic, social and organizational development in a certain space.

Some positive elements of the marketing reform in public sector include:

1. Public services providers that are acting effectively and ethically within companies;

2. Citizens/clients receiving respect, courtesy and professionalism from public services providers, while being satisfied with the required performance and better informed, thanks to greater transparency in public activities;

3. Clear, simple and accurate procedures carried out in public services enterprises;

4. Better public services in terms of quality and adaptability to meet customer needs;

5. Political neutrality.

Acknowledgement

This work was co-financed from the European Social Fund through Sectorial Operational Program Human Resources Development 2007-2013, project number POSDRU/1.5/S/59184 „Performance and excellence in postdoctoral research in Romanian economics science domain”.

References

Bean, J. & Hussey, L. (1997). ‘Marketing Public Sector Services,’ HB Publications, London.

Google Scholar

Butler, P. & Collins, N. (1995). “Marketing Public Sector Services: Concepts and Characteristics,” Journal of Marketing Management, 11: 83-96.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Cătană, G. (2003). Marketing: Filozofia Succesului de Piaţă, Editura Dacia, Cluj Napoca.

Google Scholar

Chapman, D., Cowdell, T. (1998). ‘New Public Sector Marketing,’ Pitman Publishing, London

Publisher – Google Scholar

Day, J., Reynolds, P. & Lancaster, G. (1998). “A Marketing Strategy for Public Sector Organizations Compelled to Operate in a Compulsory Competitive Tendering Environment,” International Journal of Public Sector Management, 11(7): 583-595.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Enis, B., Kangun, N. & Mokwa, M. P. (1978). ‘Marketing Perspective would Improve Public Policy Development, ‘ implementation, Marketing News, Feb. 24: 2, 4.

Graham, P. (1994). “Marketing in the Public Sector: Inappropriate or Merely Difficult?,” Journal of Marketing Management, 10: 361-375.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Hannagan, T. (1992). Marketing for the Non-Profit Sector, Macmillan, New York.

Google Scholar

Hermel, L. & Romagni, P. (1990). Le Marketing Public — Une Introduction au Marketing des Administrations et des Organisations Publiques, Editura Economica, Paris.

Google Scholar

Kaplan, A. M. & Haenlein, M. (2009). Rapprochement Entre le Marketing et L’administration Publique: Vers une Comprehension Globale du Potential du Marketing Public, Revue Française du Marketing, no. 224, 4/5: 49-66.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Kearsey, A. & Varey, R. J. (1998). “Managerialist Thinking on Marketing for Public Services,” Public Money & Management, January-March: 51-60.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Kotler, P. & Lee, N. (2007). ‘Marketing in the Public Sector. A Roadmap for Improved Performance,’ Wharton School Publishing, Philadelphia.

Google Scholar

Kotler, P. & Levy, S. J. (1969). “Broadening the Concept of Marketing,” Journal of Marketing, 33 (January): 10-15.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Matei, L. (2006). ‘Management Public,’ Ed. A II-a, Editura Economică, Bucharest.

Mitchell, A. (2005). “How Marketers can Play a Vital Role in Setting the State Straight,” Marketing Week, 15.02.2005: 24-25.

Publisher

Rainey, H. G. (2003). ‘Understanding and Managing Public Organizations,’ Jossey-Bass Publishing, San Francisco.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Ritchie, J. R. B., LaBrèque, R. J. (1975). “Marketing Research and Public Policy: A Functional Perspective,” Journal of Marketing, Vol. 39 (July): 12-19

Publisher – Google Scholar

Sargeant, A. (1999). ‘Marketing Management for Nonprofit Organizations,’ Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Scrivens, E. (1991). “Is There a Role for Marketing in the Public Sector?,” Public Money & Management, Summer: 17-23.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Walsh, K. (1991). “Citizens and Consumers: Marketing and Public Sector Management,” Public Money & Management, Summer: 9-16.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Walsh, K. (1994). “Marketing and Public Sector Management,” European Journal of Marketing, 28(3): 63-71.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct