Introduction

Overall perception about the state of quality in higher education in Romania is that of a high quality. Despite this perception, is perceivable, through the recent years, a decrease of its credibility. The quantitative research carried out brings a number of contradictory aspects related to the higher education system in Romania.

This apparent paradox between the positive valorisation of the overall image of quality and lack of confidence about the ability of universities to achieve some finality can be explained by an ambiguity in the social functions of the university. “We are still in a society where the university is perceived as a court of general, academic, to whose services would be attainable only by the best (nostalgia regarding the admission examinations is still widespread), university whose main purpose is to prepare elite”. (Lazar Vlăsceanu, Miroiu Adrian, Mihai Paunescu, Quality-Barometer 2010, p.13)

Government Emergency Ordinance no. 75/2005 on providing quality education and Law no. 87/2006 which was approved the Emergency Ordinance have assembled the legislative context which regulated quality assurance in education, and has allowed the development of an institutional culture of quality education and protection of education beneficiaries.

Despite the legislative framework that makes references to both quality control and quality improvement, HEIs has focused its priorities on external control and accreditation, reporting the quality of education at a predetermined set of standards.

Fig. 1: Main elements of the Quality Assurance System

Source: the author

The moment of truth or interface with the three largest categories of customers of the university education system, namely: students, employers and teachers involved in carrying out activities in the university, is the center of the system and the other three factors are in constant interaction with each other and with the center of the system, which directly affects him University’s management responsibility is to establish quality policy, quality objectives and responsibilities and an accurate assessment of quality in the whole university.

Management or its representatives must ensure that the quality system is properly designed, implemented, audited and reviewed continuously for a sustained improvement.

According to the representation of Figure 1 the three main categories of customers to which a university must meet the requirements are: students, employers and academics involved in providing educational services. Consequently, the mission must bring to attention the university’s concern to provide clear answers expected by the three major groups of clients, on the one hand and, on the other hand, strategic plans and then the operational ways to reveal available resources and commissioning work at the assumed mission Introduction of Quality Assurance and universities accreditation is meant to provide a powerful tool towards providing customer satisfaction, without considering this approach as consensual.

So, three out of four teachers considered that the purpose and operation of Romanian Agency for Quality Assurance in Higher Education (ARACIS) are clear. Between 55% and 75% of teachers support a system in which universities and study programs are regularly evaluated and accredited by the Ministry or other central agencies with responsibilities in this area. Quality assessment programs based on a national study of performance indicators is supported by 41% of teachers, while 26% believe that the most effective method of evaluation is based on the views of those involved in university life. (Quality-Barometer, 2010 p. 24).

The accreditation by The Romanian Agency for Quality Assurance in Higher Education aims to promote development of standards and standard-based activities improving communication and collaboration at national and international level and creating facilities for developing cooperation in the sphere of scientific, technological and economic activity. Standardization process may be interpreted as a manifestation of the growing need for a global society, for order and accuracy, and the claim that the concepts of truth and honesty are included in Assurance Quality’s purposes.

Quality standards, while continuing to meet the minimum requirements regarding the quality of education are a collection of clear guidelines, concerning the characteristics and components of quality systems, ensuring certainty for users, Audits carried out in several Romanian universities provide me the possibility of observing some confusions on the definition and, especially, the interpretation of the philosophy of quality and, by default, different views about the creation of the organization applying this philosophy . The current legislative context rewards universities that conform to standards, whether this compliance is just bureaucratic, formal, at the expense of supporting endogenous development of a strategic quality approach.

The need for this approach is imposed by sufficient standards in certain circumstances, and caps limit creativity and performance (see Fig. 2)

Fig. 2: Capping performance by standardizing

Source: the author

Quality standards refer only to provide minimal real needs of beneficiaries. In addition, considering the inherent difficulties in adapting the standards to specific activities due to insufficient training of changes imposed by adoption, we conclude that the support role of the improvement process that standards should have is, on the contrary, perceived as a barrier to continuous improvement.

The analysis of Fig. 2 revels critical to quality approach. For starters, the results that fall within the present guidelines, despite having deficiencies, are considered more likely to meet the demands of an educational services customer. In fact, customer satisfaction level is relative because he has to bear the costs of poor quality, deficiencies, human or system errors whose amplitude does not exceed the predetermined limit, (Min.). Over all other considerations, this is a matter of ethics.

Secondly, standardization is setting a quality level that has the effect of capping performance. Achieving quality levels set for the achievement of accreditation can generate a state of complacency, dangerous in terms of achieving the mission of the university, meeting the demands of the clients that are also group members of a changing society.

Homogenization is another vulnerability of the system, which is manifested both at the university’s mission of procedures and internal quality assurance mechanisms and other internal regulations (the university’s ethics for example) and in the organization of studies and processes teaching and learning (the university’s operational area). Universities tend to copy the emerging organizational models developed by universities with a tradition and reputation, thereby decreasing uncertainty about the recognition and accreditation.

Quality Barometer-2011 reproduces the results of some surveys conducted by questionnaire in the three main groups of clients: students, academics and beneficiaries. None of these are significantly satisfied about the quality of university education in Romania, though, as we have shown above, the general picture for higher education is positive.

Although it seems to be a paradoxical situation, it is understandable considering that, on one hand, the down slope of the society’s trust in the Romanian university system, and, on the other hand, it’s increase, so that in 2011, only 4% of teachers considered that over ¾ of all students with whom they work are good, 15% specified that the good are between half and three quarters of all students. 33% say that good students are less than half, and the relative majority of teachers (46%) indicate a share of good students, lesser than a quarter of the total

Focusing on results expresses the need for the creation of a strategic vision of the expected finality, vision which exceeds the orders of the organization and which takes into consideration, on one hand the fruition of the positive influences from external factors, and on the other hand reduction (elimination) of threats coming from them. Such an approach would lead to ease tensions that currently exist in the Romanian system:” Employers shall adopt a relatively neutral position, there also an important gap between the current levels of skills necessary for graduates in the minds of employers.

The employer’s perception is of a large gap between the current level of skills and the required ones. Most employers prefer graduates who have worked either part-time (40%) or full-time (26%) during college, only 7 % of employees would prefer those who have not had a job during college. On the other hand, employers prefer master graduates, and if it comes to license graduates, they prefer the pre-Bologna ones (valuing both cases, longer duration of studies it is desirable). Also, state universities are preferred to private ones.

The Concept of Diversification

Throughout the last 15 years, the development of higher education in Romania knew a strong tendency towards uniformity, which affected both the state and the private universities. Certain processes in the field of higher education attempted the diminishing of the differences between the state and private higher education institutions, as well as between the new or old, small or large, theoretical or strongly specialized institutions. Although the initial conditions were different and the differentiation was most times mentioned explicitly within the policies or institutional goals, such as the example of the private universities, which present themselves as an alternative to the state education, the state higher education institutions adopted similar structures, procedures and practices. (Adrian Miroiu, Liviu Andreescu, 2010)

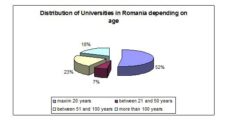

According to the quality barometer issued by ARACIS in year 2010, more than half of the Romanian universities are not more than 20 years old. From the viewpoint of tradition or age, the higher education system in Romania represents a combination of young higher education institutions, with an age not higher than 20 years and “tradition” institutions with a functioning period ranging between 50 and more than 100 years. Figure 3 presents a distribution of the higher education institutions in Romania, depending on their age. As can be seen, more than half are young universities (52%), while 41% are of “tradition”, by tradition understanding, on the one hand, universities with age over 100 years (18%) and, on the other hand, universities with age comprised between 50 and 100 years (23%) – a great part of this category being established a little after 1848, following different processes of institutional differentiation (The condition of the quality of higher education in Romania. “Quality barometer – 2010”, The Romanian Agency for Quality Assurance in Higher Education, Bucharest, 2010, p. 37-38).

Still, when we consider other indicators, we notice a high degree of institutional uniformity. The problem of the standardization process caused two types of consequences, the first being represented by the intense competition in which the Romanian universities are engaged, in order to obtain financial resources, to increase the number of students and the didactic staff, which introduced the idea of aligning the universities to the common legitimizing standards and practices, in order to be considered organizations offering valuable services. Thus, the general impression is that of the compulsory character of uniformity, for the purpose of legitimizing and identifying them among the traditional and renowned universities.

The second consequence is represented by the inhibition of the creative solutions by the uniform practices, as well as by the offering of inadequate answers to the external requirements specific to present society. In other words, this process has weakened the organizational performance of the higher education system.

The institutional uniformity was created following the emergence of three mechanisms. The first such mechanism, that of mimicry, generated a tendency of imitating renowned universities by universities with a lower legitimacy degree, this fact being emphasized by their adaptation of the organizational structures to pre-existing patterns or by elaborating new study programs, similar to those of the prestigious universities.

The normative mechanisms represent another cause of institutional uniformity, which treats the issue of access to the position of member of the teaching staff. The process developed a new tendency of taking over the actions of the old, renowned universities, and implementing them within the new ones. The most important mechanism which led to the problem of uniformity is the coercive one, the constraints that characterize this mechanism emerging as a result of the strict regulations issued by the Romanian state on the grounds of the simplification principle.

Fig. 3: Distribution of universities in Romania, depending on age

Source: Based on data provided by Quality barometer-2010.

As one may observe, the increase of the efficiency and performance of the Romanian universities is necessary, and the mechanisms required to reach this purpose are represented by the increase of differentiation of institutional practices, to the detriment of uniformity. The problem we are facing, however, is that of identifying by the universities of the correct means for increasing their determination to use incentives according to the differentiation.

The concept of entrepreneurial university is based on the idea of diversity in higher education and represents a new goal of the future public policies. The arguments in favour of institutional diversity are based on the idea of increasing organizational performances, due to the fact that the organizations are considered to have the qualities necessary for surviving in a society of continuously increasing complexity. Still, the objective of institutional diversity is not always a suitable goal for all fields, existing cases when the uniform treatment is to be preferred to the detriment of diversity (Higher Education Founding Council for England, “Diversity in higher education: HEFCE policy statement”, 2000, available at http://www.hefce.ac.uk/pubs/HEFCE/2000/00_33.htm;)

For instance, in the problem of quality assurance in the educational programs, it is necessary to establish a minimal quality standard, and in the problem of subsidizing policies is considered necessary the observance of a balance between distinct objectives such as institutional diversity, institutional viability, as well as the correctness of the different institutional typologies. Also, in case of public responsibility, the higher education institutions must not be the object of institutional diversity, being considered responsible for the manner in which they spend public money, but also having the freedom to spend them in different legitimate ways, in order to reach their purposes.

The Instruments of Diversification

The changes in the external environment of the higher education institutions may have a non-institutional character, the students’ life-style and values may be altered, the number of students may vary, such as the “customers” of universities may change (for example, universities can focus more on developing life-long learning, more precisely, on more elderly persons). These external changes may require prompt answers from the higher education institutions, as they can also lead to a certain differentiation, independent of the institutional context in which universities are classified (Adrian Miroiu, Liviu Andreescu, op.cit., p. 96, apud Cf. M.S. Kraats, E.J. Zajac, “Exploring the limits of the new institutionalism: The causes and consequences of illegitimate organizational change”, American Sociological review, 61, 1996, pp. 812-836)

The most important differentiation mechanisms are the institutional ones, such as changing the rules, the regulations for governing the actions of higher education institutions, as well as the newly established special practices.

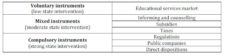

The basic typology of the instruments that can be used for achieving the institutional diversification of universities takes over the pattern of the public policies instruments, presented in the previous chapters, namely the division in three main categories (see Fig. 4).

These are voluntary instruments, which presuppose the low intervention of the state, having as example the market of educational services, mixed instruments, characterized by the moderate state intervention, by means of its components, subsidies, taxes and information and counselling, as well as the compulsory instruments by means of which the state peacefully imposes its intervention in a strong way, composed of regulations, public companies and direct dispositions (M. Howlett, M. Ramesh,1995)

Table1: Basic typology of the instruments used for the institutional diversification of the universities

Source: Adaptation after Adrian Miroiu, Liviu Andreescu, “Quality Assurance Review for Higher Education – Goals and Instruments of Diversification in Higher education”, ARACIS, Bucharest, September 2010, p. 97

The state must support public higher education institutions, especially with respect to the financial financing, since it is able to use its importance in order to influence and even constraint the institutions towards reaching the differentiation objective.

Transformation by Quality strategic approach –a possible scenario of transition from homogeneity to diversity in Higher education

Quality Concept

Scenario building is based by a holistic approach of Quality concept in sense given by “Robert Pirsig” Quality is the fundamental creative force in the universe stimulating everything, from atoms to combine to make molecules, to what causes animals to evolve and incorporate ever greater levels of Quality. …..everything (including mind, ideas and matter) is a product and a result of Quality! Quality therefore is not just diversity-friendly, it creates diversity! (Robert Pirsig the Metaphysics of Quality cited by Rob Carmichael in Creativity and Diversity: Challenges for quality assurance beyond 2010 ‘Zen, Motorcycle Maintenance, and the Metaphysics of Quality’, p.3)

These means that Quality lies in the dynamic “Now” moment that we sense anything during the instantaneous present, whit a short delay we give this impression a static form by describing it as an emotion, a thing, a word, etc.

These „static forms‟, if they have enough good or bad quality associations, are given names and ideas about them are interchanged with other people, building the base of knowledge for a culture. Quality then according to Pirsig is fundamentally a continuing dialogue between our personal (internally-referenced, subjective, and creative) values and beliefs, and a publicly-accepted (i.e. objective, externally verifiable, predictable) construction of reality. From how Robert Pirsig defines quality is evident that being excellent in what we do, and being „fit-for-purpose‟ mean essentially the same thing.

Thus, according to Pirsig, the internal (creative/diversity) and external (predictable/standardizing) dimensions of quality, rather than being at opposite poles, fuse into a more holistic concept of Quality.

Quality Strategic Approach and Diversity in Higher Education

Such an approach is closely related by a deeply understanding of the dynamic of the economic condition, respectively on the one hand, and the increasing acceptance of risk and uncertainty such an attitude of thinking should stimulate the progress and , on the other hand, redefining the future of HEIs in terms of new realities.

From the perspective of this work, success of Quality strategic approach is directly link to identify all stakeholders and called into question how values achieved in HEI is distributed between client groups: students, employers, purchasers of HE services, and the wider community.

Widening the circle of interests inside and outside the university, while dividing and grouping the entities inside of this space are challenges which management of university should assume. In addition, determining the relations established with each of the client groups allow identification the university mission and objectives hierarchy. Diversity within institutions depends largely on the determination of individual universities and colleges to take the initiative in identifying and building a mission for themselves which will best meet the disparate needs of the students, employers, and other partners they are seeking to serve.

Philosophy governing the strategic approach initiated for to achieve these objectives tends to create new paradigms, also contributed to the crystallization a new type of thinking and behaviour characteristic of Quality Strategic Management.

Integrating of Quality Strategic Management in university management is facing with major difficulties which arise, in particular, from the obligation of giving up the traditional management scheme. According our own estimations, the introduction of this new philosophy attempts failed because of inability to align with new requirements.

The creation of a context to initiate the quality strategic approach has revealed the fact that a structural change is necessary in HEI. The premise we based the approaching on this organizational transformation is that integrating the strategy of Quality in general strategy of the university is a complex process, in which the management have to take account of the consequences on the organization itself. From this view, the strategic demarche of Quality is formulated according to a macro vision about the university and consists in the ability of orchestrating simultaneous transformations of each system in the university.

According to our theory, integrating the strategy of quality in the general strategy of the organization is materialized in a complex transformation, oriented of four dimensions (see fig. 5): (1) Redefining the potential of the organization. (2) Reorganization the organization. (3) Revitalization the portfolio of the organization. (4) Reviving the mentality of members of the organization. (L.G.Popescu, 2007)

Fig. 4: Transformation of the organization by Quality strategic approach

Source: the author

The optimistic scenario in this transformation is that the organizations can “revive” and not in a paternalist manner, but through the development and assumption of new responsibilities as part as new social contracts.

In this new framework, the traditional relationship, purely legal customer/client-provider of education is replaced by a relationship of cooperation and creative collaboration between the main actors in higher education system.

We can see the result of this deep change determined by the principles on which the new type of relationship develops; from the traditional type where the clients c (students and employees) was “stopped at the gate of the university” to the new one where he becomes co -participant throughout the new quality cycle: co-design, co-decision, co-produce and co-evaluation.

Achievement means giving up old paradigms and acceptance of some innovative approaches in which client-groups are, at the same time, co-participants in the innovation of the higher education system they benefit from.. Such a transformation by integration of Quality strategic approach is meant to set up a space of diversity as benchmarks set by J. Taylor “A diverse higher education sector is one with the capacity to meet the varying needs and aspirations of those it serves: students, employers, purchasers of HE services, Those needs and aspirations are becoming increasingly varied, most obviously in the expectations, abilities and circumstances of students as participation in higher education gets progressively wider, but also in the understanding of how higher education can contribute to the economic, social and cultural development of the nation.

In this sense, diversity of HE provision is not an end in itself. It is a means of securing the best fit with the needs and wishes of stakeholders, both current and future.

Diversity is valuable to the extent that it helps to improve that fit. It should develop and expand to keep pace with changing circumstances, and should itself help to shape and raise aspirations and expectations. “(J. Taylor, 2003)

Consequently, the enforcement of such complex changes means revitalizing a sector which is able to move from the homogeneity to diversity.

Unfortunately, the Romanian higher education system is not designed foster institutional diversity, to reward innovation and encourage social entrepreneurship, but rather a pattern of favouring one academic development, generalizing quality standard conditions for a quantity growing service users, consequently, the general view of students is that the university is not an institution to generate senses or provide directions. Thus, “students appear to be alone and insecure in the face of uncertainty in relation to the type of training they receive in the university” (Quality Barometer-2010, p.22)

Conclusions

In conclusion, as it represents an important step in customer satisfaction, standardization must be entered into a global effort to integrate the quality strategic approach into global strategic approach of the university.

Conditionality between the quality standards and strategic approach derives from the fact that no matter how powerful it would be, the standard alone can not stimulate creativity, motivation and mobilization of human resources, the key factors for a truly diversified educational offer which is modeled on the needs of the students, and also on the needs of the other two groups of customers: employees and academics.

The model of strategic quality approach will not only eliminate the danger„homogeneous practices which have been inhibiting creative solutions and, conversely, have encouraged responses that do not always represent an adequate answer to external demands. In other words, the process has weakened organizational performance, but it involves creating internal organizational system that supports responds more flexibly to signals from society; leads to a more accessible higher education; it provides students with a larger range of options, and lets HEIs capitalize on their strengths in order to meet the needs and abilities of the students.

Institutionalizing the strategic quality approach allows different universities to decide which part research should play in their mission, and to identify areas where they will seek to demonstrate research strength in the periodic research assessments. Strategic quality approach expresses a differentiation and adaptation driven by demand from environment, and from this perspective we are able to examine a variety of strategic organization behaviors for example, whether a higher education institution anticipates or reacts to discontinuities in the environment. The management of this kind of university is able “to work today for tomorrow.” In this context, the managerial approach has a twofold focus: (a) to solve current problems and (2) to anticipate problems that will face.

By contrast, in the freeze universities, there are positioned managers who “just look carefully where they go, but never at the sky.” They are only interested in the present, but completely ignore the future. Such managerial behavior demonstrates lack of strategic vision, and, obviously, the lack of performance.

In this new context a high degree of flexibility and adaptability of higher education systems gives the opportunity to meet societal demands in real time, demands which are in constant change. To outline of a new entrepreneurial management context based on results first means the necessity to create new models of inter-relations development between and within institutions. Secondly, there is an imperative demand for structural changes within the universities, in order to maximize efficiency (so that they become compatible with flexible structures – network type) and increase the capability in decision-making through involvement of students/customers and representative interest groups for communities.

References

Guskin, A. (1994) Part II: Restructuring the Role of the Faculty, Change 26, no.5: 16-25.;

Publisher – Google Scholar

Gilles, P. (1994) New Patterns of Governance, Kenneth Press, Ottawa;

Harvey L. (2000) New Realities: The Relationship between Higher Education and Employment, Tertiary Education and Management;

Publisher – Google Scholar

Harvey, L., Knight, P.T. (1996), Transforming Higher Education, Buckingham: Society for Research into Higher Education (SRHE) and Open University Press;

Harvey, L., Moon, S., Geall, V. Graduates (1997), Organizational Change and Students’ Attributes, Birmingham: Centre for Research into Quality (CRQ) and Association of Graduate Recruiters (AGR);

Miroiu, A., Andreescu, L. (2010), Goals and Instruments of Diversification in Higher Education, 2010, Quality Assurance Review, Volumr.2, No.2;

Morgan, G. (1989) Creative Organization Theory, Newbury park, California, Sage Publication;

Pollitt, C., Bouckaert, G., Loffler, E. (2006), Making Quality Sustainable: Co-Design, Co-Decide, Co-Produce, and Co-Evaluate, Report of The 4QC Conference, Tampere;

Politt C., and Bouckaert, G. (1995), Quality Improvement in European Public Services, SAGE Publication Ltd. London;

Popescu, L.G., (2012) Strategic Responsiveness and Market Repositioning in Higher Education, LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing GmbH & Co., Saarbrücken, Germany,

Popescu, L.G, et. al. (2012), Strategic Approach of Total Quality and their Effects on the Public Organization, in Total Quality Management, InTech – Open Access Publisher

Popescu, L.G (2007) The innovation of the Public services by Quality Strategic Approach, Transylvanian Review of Administrative Science, nr. 20(E), pp. 63-80.

Lomas, L. (2007) Zen, motorcycle maintenance and quality in higher education , Quality Assurance in Education, Volume 15 No 4, pp. 402-412;

Publisher – Google Scholar

Pirsig, Robert M. (1974) Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance – An Inquiry into Values, Boadly Head, UK. in Woodhouse, David, Introduction to Quality Assurance, 2009, AUQA;

Scott, P. (1995) The Meanings of Mass Higher Education. Buckingham: Society for Research into Higher Education (SRHE) and Open University Press;

Stein, F.R. (1999) The next phase of Total Quality Management, Marcel Dekker Inc., New York,

Quality Barometer-2010, Romanian Agency for Quality in Higher Education;

Taylor, J. (2003) Institutional Diversity in UK Higher Education: Policy and Outcomes Since the End of the Binary Divide – Higher Education Quarterly, – Wiley Online Library;

Vught, Frans van , (2009) The EU Innovation Agenda, Challenges for European Higher

Education and Research, Journal for Higher Education Management and Policy, Vol. 21/2