Introduction

Change or transformation activities have found their way onto managers’ regular agendas. Change is driven by the globalization trend, the importance of ethical and social responsibility, the higher speed of responsiveness, the digital workspace and diversity (Daft, 2007). In some situations, these trends change the fundamentals of an industry, which dramatically influences organizations’ business models. This type of change is often called ‘disruptive’ (Christensen, 2006).

The discipline of Change Management or Change Leadership has been intensively developed through professional publications for several decades. These publications provide a lot of recommendations on successful change. For example, Kotter, 1996 emphasizes eight steps to drive change toward its goals starting with planning the activity (sense of urgency, teaming, vision and strategy developing), preparing the organization for change (communication of the change, empowering people) and capitalizing on success (quick wins, supporting another change, anchoring the change results in culture).

Unfortunately, in spite of the recommendation on successful change, a range of change activities still fail. Many authors state that the failure rate is about 70 per cent (e. g., Kotter, 2008). IBM’s comprehensive study on the success of change (IBM, 2008) reports a 59 per cent failure rate. They indicate the major causes consist of a combination of factors: an insufficient understanding of the organization’s current landscape or the impacts of change on the organization, the change team lacks the necessary capabilities, or the change is not supported enough by the organization.

In my previous research, I focused on the utilization of Enterprise Architecture, Organizational Complexity and the Resource-based View in the planning stage of a change (Hladik, 2012). This framework helps us to better understand the key drivers of the change and the major resources of the organization that can be impacted by the change. The framework enriches the change planning procedure and therefore it can prevent the potential troubles caused by the incomplete change method.

Enterprise Architecture’s purpose is to support change activities. It provides a procedure (also called ‘process’) of how to manage a change from the planning stage to its execution (for example, Architecture Development Method or ADM by The Open Group, 2009), as well as an approach to understand, analyze and (re)design the organization’s landscape (architecture layers). On basis of my observation, Enterprise Architecture’s standard approach does not include the social and human aspects of the organization, which are critical in order for any change to succeed (Luecke, 2003).

Regarding the social and human aspects, the question is: what exactly is important for a successful change? Organization theory (for example Daft, 2007) accentuates the significance of the organization culture that is defined as the underlying set of key values, beliefs, understandings, and norms shared by employees. Though it is often difficult to analyze and manage the organization’s cultural elements, for example it helps to understand the organization’s readiness for change or major influencing sources (that can support or defend against the change). I see this as an opportunity to better understand the organization in the planning stage of the change.

The framework to support a successful change within an organization outlined in this paper is based on two Enterprise Architecture principles: the process of change planning and execution (for example ADM by The Open Group described above), and the layered view of the organization (e. g. business-, application-, technology architecture defined by Lankhorst, 2009). Business architecture describes business functions, services, processes and the other elements of a real organization. My contribution extends Enterprise Architecture to include the social and human view (as influencing sources), which should be understood and mapped into business architecture’s standard views. The combination of these two methods will help to manage the change more effectively (i. e. utilize or engage the right people, properly address suitable messages, identify the human-related risks). The objective of this paper is to introduce this framework and list the reasons for its existence and further development.

How Should Change Be Managed?

Change Management is one of the major managerial theory topics and has been broadly studied, researched and documented. In this paper, Change Management is used in the context of whole organizational change. Kotter, 1996, distinguishes between Change Management and Change Leadership. Change Management is defined as the utilization of basic structures and tools to control any organizational change effort. On the other hand, he understands Change Leadership as the driving forces, visions and processes that fuel a large-scale transformation. Based on my findings above, I consider both to be critical for a successful change. Therefore, in this paper the term ‘Change Management’ will include all the important aspects of the change, including the social and human aspects.

I analyzed Change Management resources to identify the key success factors, the recommended methods and the best practice, which should prevent a change from failing. For example, Kotter outlined the following eight critical success factors: establishing a sense of urgency, creating a guiding coalition, developing a vision and strategy, communicating the change vision, empowering employees for broad-based action, generating short-term wins, consolidating gains and producing more change, and anchoring new approaches in the culture. A similar view of the ‘seven steps’ to a successful change was defined by Beer and Eisenstat (Luecke, 2003).

Luecke summarized a number of books and articles about Change Management authored by Beer, Spector, Eisenstat, Nohria and Kotter. His expert recommendation depends on the type of change and can be focused on an economic matter (called ‘Theory E’) or an organizational capabilities matter (called ‘Theory O’). The whole recommendation is made up of six factors: goals, leadership, focus, process, a reward system and the use of consultants. Luecke emphasizes the importance of the social and human factors that are critical for any organizational change. He especially emphasizes a need to identify ‘the resisters’ and utilize ‘the change agents’. The resisters are individuals or groups of individuals who refuse the change or are not able to adapt to the change. On the opposite side, the change agents support the change, are members of the organization (i. e. employees) and are recognized by the others as good leaders.

In my observation, I identified three critical areas that are composed of the resources quoted above that should be addressed during the change, and will be used further in my work:

- Understanding the Situation: understanding the current organization landscape, the change vision and goals, and the change impacts on the organization itself.

- The Change Team: a skilled, experienced and equipped change team; by ‘equipped’ I mean possessing all the necessary tools and methods required by the practice of Change Management.

- Support from the Organization: including management’s commitment to execute the change as well as the readiness of the organization to absorb the change.

How Has Change Been Managed in Reality?

Many Change Management resources mention that the organization absorbs changes with troubles, specifically with a change failure rate of about 70 per cent (Kotter, 2008). Even though it is debatable how much and what kind of change failure occurs more than another (for example, Hughes, 2011). IBM’s Institute for Business Value conducted a comprehensive study on Change Management (IBM, 2008) providing reliable results. They surveyed 1,500 people representing various organizations around the globe. This study shows that 41 per cent of changes met their objectives and therefore, were marked as successful. Unfortunately, another 44 per cent did not meet either their time, budget or quality goals, and the last 15 per cent did not meet any goal or were stopped.

It also confirms a significant gap between the most successful organizations (20 per cent failure rate) and the others. These organizations performed their change activities according to plan in 80 per cent of cases, which means they were twice as good as the rest. The top five barriers to change, as identified by respondents, were: changing mindsets and attitudes, the organization’s culture, underestimated complexity, a shortage of resources, and a lack of commitment from senior management.

The IBM study proposes four important areas of focus to succeed in change (called the ‘change diamond’): real insights (realistic understanding of the change’s challenges and complexities, followed by the actions associated with them), proven methods (the use of a systematic approach, focused on outcomes and aligned with formal project management methods), better skills (proper senior management support, dedicated change managers and an empowered change team), and a suitable investment (the allocation of a reasonable budget, an understanding of possible scenarios and their returns on the investment).

Another interesting point of this study is related to the Change Management method. 87 per cent of respondents said that formal methods are needed, but only 24 per cent of them confirmed that they had used some formal methods in the change activity.

This IBM study fully confirms the Change Management theory’s recommendation described in the previous chapter. The study’s change diamond encouragement also proves my three critical areas of successful change (‘real insight’ as well as ‘suitable investment’ are covered by understanding the landscape; ‘solid methods’ are a part of the change team, and ‘better skills’ are connected to both support by the organization and the change team).

To conclude my study on Change Management resources, I can state that both Change Management theory and research on real organizational change confirm the same or similar causes of change failure as well as the same recommendations for their prevention. They prove that the social and human factors of the organization and change are really critical for change success. I believe it acts as a reasonable justification of the change management framework I am going to introduce in this paper.

Enterprise Architecture’s View on Change Management

The nature of the Enterprise Architecture method is to support organizational change (for example, see the definition of the purpose of Enterprise Architecture by The Open Group, 2009). The process of Enterprise Architecture development starts with understanding an organization’s strategy and strategic goals, as well as the organization’s current landscape impacted by the strategy. Then based on the strategy, the target situation is designed and a road map of the change is defined. This is a suitable method how to manage the change.

Unfortunately, Enterprise Architecture methods usually only address an organization itself without including the social and human dimension of the organization. They use a layered view of the organization, fragmented into business-, application- and technology- architecture (or layer). Both application and technology architectures are related to information technology systems. Business architecture describes business functions, services, processes and the other elements of a real organization (Lankhorst, 2009, or The Open Group, 2009). All these business architecture views practically exclude the social and human aspects of the organization.

A similar situation exists with the Federal Enterprise Architecture framework (FEA) (US Federal Government Office, 2007) that is developed for the US administration’s organizations. FEA provides more specific methods than TOGAF, especially in change planning and organization performance measurement. However, the social and human components of the organization are also missing.

In order to fully comprehend the change management framework that I present in this paper, it is important to understand how Enterprise Architecture methods suggest addressing the business architecture layer that would be enriched by the social and human dimension. TOGAF recommends starting with a business footprint diagram describing the links between business goals, organizational units, business functions, and services. It suggests the usage of other modeling techniques as well. Lankhorst, 2009 presents the ArchiMate method introducing a two-way approach to modeling the business architecture: business structure concepts (i. e. a business actor, a role, collaboration, an object, etc.), and business behavior concepts (i. e. a business service, a process, a function, an interaction, etc.).

The mapping between the social and human dimension and business architecture’s standard views should be implemented on the levels of business goals, organizational units (or structure), and eventually business functions. I recommend mapping these elements with at least the readiness of the organization to change, the change’s influencing sources, and the communication strategy.

The Specific Characteristics of an Organization and Its Change

It is always difficult or impossible to develop a method without a reasonable understanding of the subject which the method is focused on. Therefore, I studied the Organization Theory to better understand organizations, their types, structures, behaviour and other aspects. Daft, 2008 defines an organization as follows: organizations are social entities that are goal-directed, designed as deliberately structured and coordinated activity systems, and are linked to the external environment. Additionally, this definition is similar to System Theory’s definitions of the organization (for example Jakson, 2003).

Daft defines the structural and conceptual types of organization design dimensions. The conceptual dimensions include: formalization (how structured the organization is, managed by formal rules, etc.), specialization (from a division of labour point of view), the hierarchy of authority, centralization (where decisions are made in the hierarchy), professionalism, personnel ratios (for example, the ratio of indirect to direct labor employees). The contextual dimensions are: the size of the organization, technology, the environment, the organization’s goals and strategy, and the organization’s culture (see explanation above).

Some of these dimensions are recognized by the Enterprise Architecture approach, the business architecture view (for example: goals and strategy, the size of the organization, technology, specifically the environment, and hierarchy-related dimensions). On the other hand, the social and human dimensions are not included (organization culture and the other conceptual dimensions, relevant from the organization’s ability to change its point of view).

Daft emphasizes five elements which are necessary for organizational change: ideas (the organization’s internal ability to identify opportunities to change), need (the confirmation of an idea from a business perspective), adoption (mainly the support of the change), implementation (performing change activities), resources (people who are generating the ideas, supporting or performing the change).

The Organization Theory (here represented by Daft, 2008) complements my idea on how to align standard Enterprise Architecture’s techniques with the social and human aspects of the organization. The key contribution of Organization Theory is organization culture, which covers almost all the human-related recommendations by the Change Management theory and practice.

The Change Management Framework

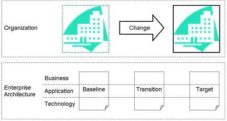

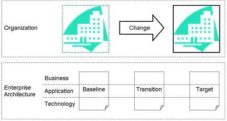

Change management framework’s foundation comes from the standard approaches of Enterprise Architecture, Enterprise Architecture’s process (e. g. ADM by The Open Group) and the layered view of the organization. Enterprise Architecture’s process supports the understanding of the organization’s current landscape (baseline architecture) and the changed landscape in the future (target architecture). In case of a large change, it is recommended to progress in steps (or phases) that are defined by partially changed architectures (transition architecture). Baseline-, transition-, and target architecture all describe the organization by using a layered view: business-, application-, and technology architecture. For the purpose of this paper, it is important to focus on the business architecture that relates to the social and human dimension of the organization. The framework’s foundation is illustrated in fig. 1, using TOGAF’s specifics. It can be adapted to Enterprise Architecture methods’ specifics as well.

Fig 1. Enterprise Architecture Process as the Foundation of the Change Management Framework (Source: Author)

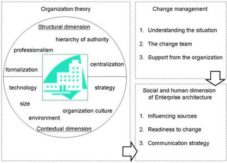

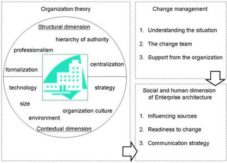

The important social and human aspects for successful change are identified based on the three critical areas specified above (understanding the organization, the change team, support from the organization), and organization theory (for example Daft, 2007). I suggest extending the business architecture view by focusing on the following social and human aspects (see fig. 2):

- Influencing Sources: the identification of the resisters and supporters of the change; these can be people as well as the setting or culture of the organization. Between the human supporters, it is recommended to nominate the change agents (see definition above).

- Readiness to Change: a systematic analysis of the organization’s ability to adapt itself to the change; it includes both the human as well as the structural aspects of the organization (for example, the identification of critical human resources that can be affected by the change), and provides information for transformation planning.

- Communication Strategy: the plan and governance of communicating the change inside and outside the organization.

During change planning and defining business architecture according to Enterprise Architecture, these social and human aspects become a part of the analysis because of their interconnection.

For example, changes in the organization’s structure or a business function’s sourcing are closely influenced by people. Therefore, analyzing such human aspects changes can prevent specific risks related to the influencing sources, help to design the right transformation plan, etc.

Fig 2. Identification of the Social and Human Aspects of Change Management Framework (Source: Author)

Conclusion and Further Research

Organizations have to adapt to survive in their markets due to trends influencing their business environment. Unfortunately, they face significant difficulties when approaching the changes, as 60 to 70 per cent of the change activities fail. On the other hand, the theory and practice of Change Management provides a thorough explanation of the troubles’ causes as well as recommendations for successful change.

In my research, I focus on supporting change by utilizing Enterprise Architecture methods. Though these methods provide a reasonable approach to Change Management, I have found that there is a gap between these methods and the recommendations for successful change in the social and human dimension of the change. Therefore, I suggest an extension of Enterprise Architecture methods to include this dimension and incorporate it into the business architecture view.

With this paper, I provide arguments explaining why social and human aspects are critical in the successful change of organizations, and introduce the utilization of these aspects in Enterprise Architecture methods as an extension of the business architecture. I believe this approach can help an organization to manage changes toward their strategic goals. In my future work, I will design a related extension of business architecture’s modeling techniques and prove the whole framework through practical use.

Acknowledgment

This paper describes the outcome of research that has been accomplished as part of a research program funded by the Grant Agency of the Czech Republic (grant no. P403-10-0303).

References

Christensen, C. M. (2006). ‘The Innovator’s Dilemma,’ New York, Harper Collins Publishers, ISBN: 978-0-06-052199-8.

Daft, R. L. (2007). Organization Theory and Design, Mason, Thomson South-Western, ISBN: 0-324-40542-1.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Dooley, K. (2002). ‘Organizational Complexity,’ In Warner, M. (ed), International Encyclopedia of Business and Management. London, Thomson Learning.

Google Scholar

Doz, Y. & Kosonen, M. (2011). ‘Fast Strategy. How Strategic Agility Will Help You Stay Ahead of the Game,’ Prague, Management Press, ISBN: 978-80-7261-227-7.

Hladik, M. (2012). ‘Application of Enterprise Architecture Supported by Organization Complexity and Resource-based View,’ Instanbul, 18th IBIMA Conference, ISBN 978-0-9821489-7-6.

Hoogervorst, J. A. P. (2004). “Enterprise Architecture: Enabling Integration, Agility and Change,” International Journal of Cooperative Information Systems (World Scientific), ISSN: 0218-8430.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Hughes, M. (2011). “Do 70 Per Cent of all Organizational Change Initiatives Really Fail?,” Journal of Change Management, ISSN: 1469-7017.

Publisher – Google Scholar

IBM Corporation (2008). “Making Change Work,” [Online], [Retrieved September, 2011], http://www-935.ibm.com/services/us/gbs/bus/pdf/gbe03100-usen-03-making-change-work.pdf.

Publisher

Jakson, M. C. (2003). Systems Thinking: Creative Holism for Managers, Chichester, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN: 0-470-84522-8.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Kaplan, R. S. & Norton, D. P. (2006). Alignment: Using the Balanced Scorecard to Create Corporate Synergies, Prague, Management Press, ISBN: 80-7261-155-0.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Kotter, J. P. (1996). Leading Change, Boston, Harvard Business School Press, ISBN: 0-87584-747-1.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Kotter, J. P. (2008). A Sense of Urgency, Boston, Harvard Business School Press, ISBN: 978-1422179710.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Lankhorst, M. (2009). “Enterprise Architecture at Work: Modelling, Communication and Analysis,” Dordrecht, Springer,ISBN: 3642013090.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Luecke, R. (2003). Managing Change and Transition, Boston, Harvard Business School Press, ISBN: 978-1422131770.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Ross, J. W., Weill, P. & Robertson, D. C. (2006). “Enterprise Architecture as Strategy: Creating a Foundation for Business Execution,” Boston, Harvard Business School Press, ISBN: 1-59139-839-8.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Schwandt, A. (2009). Measuring Organizational Complexity and its Impact on Organizational Performance – A Comprehensive Conceptual Model and Empirical Study, A Doctoral Thesis, Berlin.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Steger, U., Wolfgang, A. & Maznevski, M. (2007). Managing Complexity in Global Organizations, Chichester, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN: 978-0-470-51072-8.

Publisher – Google Scholar

The Open Group (2009). “TOGAF Version 9,” [Online], [Retrieved September, 2011],https://www2.opengroup.org/ogsys/jsp/publications/mainPage.jsp, ISBN:978-90-8753-230-7.

Publisher

US Federal Government Office (2007). “FEA Practice Guide ‘Value to the Mission,” [Online], [Retrieved September, 2011], http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/assets/fea_docs/FEA_Practice_Guidance_Nov_2007.pdf.

Publisher

Van den Berg, M. & van Steenbergen, M. (2006). Building an Enterprise Architecture Practice: Tools, Tips, Best Practices, Ready-to-Use Insights, Dordrecht, Springer, ISBN: 1402056052.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Winter, R. & Fischer, R. (2006). “Essential Layers, Artifacts, and Dependencies of Enterprise Architecture,” The 10th IEEE International Enterprise Distributed Object Computing Conference, ISBN: 0-7695-2743-4, 2006, Hong Kong, China.

Publisher – Google Scholar