Introduction

The world is changing due to several factors, from technological progress to active life time increase, from rushing for resources to huge gaps between the rich and the poor, from climate change to population aging, from global to national specific. All this and more so are the challenges for the world of work. One of the important problems of the global world today is the psychosocial risks that are perceived as more challenging than others, according to the Second European Survey of Enterprises on New and Emerging Risks – ESENER-2 in 2014 (EU-OSHA 2015a). Psychosocial risks and occupational/organizational stress in particular are problems studied by many specialists (Anisman 2014; Băban 1998; Bodea 2012; Cooper, and Marshall 1976; Cox, 1978; Cox and Griffiths 2010; EU-OSHA 2000; Floru 1974; Golu 1981; Holt 1982; Kalimo, Lindström, and Smith 1997; Lazarus and Folkman 1984; Spielberger 2010).The literature has defined and identified some theories and factors associated with stress (the Demand—Control theory of Karasek (1979), the Person—Environment Fit theory of French, Caplan and Van Harrison (1982), the Transactional theories of Lazarus (1990)).

Stress, whose pioneer is Hans Selye (1956) and named it for the first time in the so-called “general adaptation syndrome” and describes it as a reaction of biological organisms to stress, concerned more and more specialists over the time. Analyzed, the “general adaptation syndrome” consists of 3 phases: alarm phase, resistance phase (defense), burnout phase. Stress occurs whenever appears an outstanding imbalance between request and responsive possibilities of the body. The European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA) defines “work-related stress is experienced when the demands of the work environment exceed the workers’ ability to cope with (or control) them” (EU-OSHA 2012, p.21). In the paper National Standard Competences of Project Management Version 3.2 — Web defines stress as the” physical and psychic state of a person responding to a situation perceived as burdensome or threatening. Response to subjectively perceived stress is manifested on the level of experiencing, cognition, behavior and bodily symptoms” (Pitas et al. 2012, p.329). Stress is defined by the United Kingdom Health and Safety Executive (Health and Safety Executive UK), as a reaction of defense that people show in case of excessive pressure or other types of requirements addressed to them.

“A recent Eurobarometer survey by the European Commission found that 53% of workers believe that stress is the main safety and health risk they face in the workplace, and 27% of workers reported experiencing ‘stress, depression, anxiety’ caused or worsened by work during the last 12 months” (2014, p.5). EU-OSHA’s European Survey of Enterprises on New and Emerging Risks (ESENER) (2010) found that over 40% of employers consider psychosocial risks more difficult to manage than ‘traditional’ occupational safety and health risks (EU-OSHA 2013, p.6). In the European Union, stress affects 30% of the employees of the EU, and in Europe more than 40 million people are affected by stress due to their place of work. Because of this, preventing stress at work constitutes one of the objectives set out in The Statement of European Commission regarding the new strategy in the field of safety and health at work. According to the World Health Organization’s Convention, stress at the workplace leads to discomfort and/or physical, mental and/or social malfunctioning. Stress in the workplace is responsible for millions of working days unused each year and for millions of sick leaves. Although it is difficult to determine how and how much it contributes in generating accidents at work, it is proven that stress competes in producing many events. Although the numbers which reflect the human and monetary losses are significant, many organizations do not have the magnitude of the problem (EU-OSHA 2014). “At the national level, the cost for businesses and society is estimated to run into billions of euros” (EU-OSHA 2015b, p.5).

That is why it is very important to analyze the phenomenon from a statistical point of view and from the laws of variation point of view, to determine trends in the evolution of the phenomenon. Moreover, interdisciplinary research ensures an overview of the phenomenon and the best measure to be taken. The present work is part of broader research through which it analyses the situation in the mining and energy sector, represents a novelty in terms of study and apprehends stress as a phenomenon at all viable JIU Valley mining and Branches of Deva Electric Power Factory and Paroşeni Electric Power Factory.

Methodology and Aria of Research

The pilot study of research, which we present in this paper, was prepared on the basis of the results obtained as a result of organizational stress questionnaire interpretation, administered during the period May-June 2015 from employees at Exploatarea Miniera Lonea (E.M. Lonea), branch of the Energetic Complex Hunedoara (CEH), one of the viable mines (Bodea,et al. 2015).

Morbidity is considered to be an essential indicator of health status it is representing the phenomenon of illness in a community over a period of time (Bodea, Bozdog & Burdea 2013; Marica, Irimie & Băleanu 2015). Knowing the economic and social effects of the disease, as well as the statistical data on the prevalence of occupational diseases, diseases related to chronic diseases, the indicators of morbidity with temporary incapacity for work (ITM) E.M. Lonea was chosen for the pilot study. The choice is based on the existing situation in E.M. Lonea, which according to the index of gravity is the place with the most days of the ITM, with most illnesses and diseases related profession, has index of gravity (IG) highest tumors, tuberculosis, Musculoskeletal diseases at CEH.

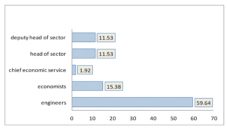

Research methodology uses questionnaire as an instrument of research. Organizational Stress Inventory questionnaire (O.S.I.) includes a battery of seven tests with corresponding assessment scale and each test has a different number of items (182 items total) adjusted to the level of understanding of the target group (Irimie et al. 2015, p.64). After collecting the applied questionnaires, processing was made on the basis of realizing a database and interpretation of the results obtained. The research area consists of 334 people, of which 77 subjects represents managerial staff (MS), quality certified by the professional risk assessment, as well as 257 subjects – execution staff , workers employed in various professions. Administered questionnaires were filled out correctly, so valid for 52 people in category MS and 103 people in the other category, the rest are partially completed questionnaires and are not valid in statistical processing. This situation is explicable through the great disadvantage of sociological inquest questionnaire based method to self-administration data collection. Category MS fits all leaders starting from the level of the mine director and up to the head of the brigade.

The Interpretation of the Results

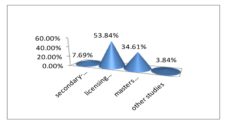

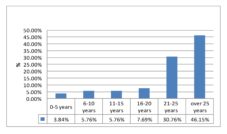

Analysis of the demographic factors has taken into account several criteria for structuring the research area: average age, sex, marital status, family supporters, number of children, level of education, seniority, seniority in the workplace, the number of hours that are required to work per week, number of hours per week worked for real, who is the person who decides to work so many hours the post office, job and the level in hierarchy. Next, presenting and commenting some of those results.

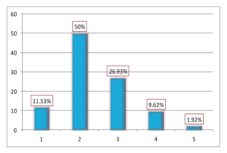

– Considering the sex of subjects, a number of 52 decision makers are divided as follows: 32 subjects (61.53%) male and 20 subjects (38.47%) female. The share of about 40% of female staff is due to the inclusion of personnel TESA within the E.M. Lonea Staff.

– The average age of MS to this unit is 44.8 years, an advanced age for mining field.

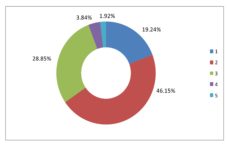

– For the employees having a partner alongside, the question arises of whether this one works. Thus, 35 subjects (67.30%) the partner is working and for the 17 subjects (32.70%) do not work, so there is one sustainer in the family.

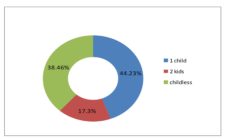

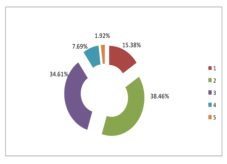

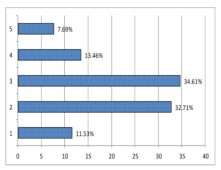

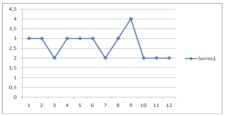

– Number of children notes that 23 subjects (44.23%) have 1 child, 9 subjects (17.30%) have 2 kids and the rest of the 20 subjects (38.46%) are childless (Figure 1).

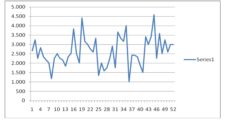

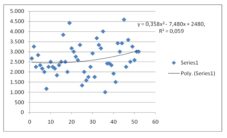

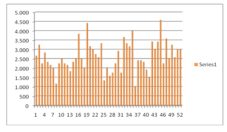

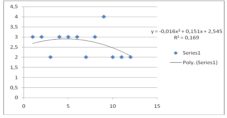

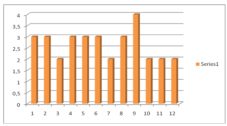

The charts reflect variation law in all the 12 items of test 1 and subject S1 from the functional matrix, for concise approach in this paper. The research was carried out using this approach for each topic deciding factor, and the whole set of subjects to describe a law of general variation. This law describes the phenomenon for the entire target group of decision makers.

To all the other chapters these mathematical approaches can be applied, quantification and determinations of the law of change of overtaken phenomenon by each chapter, an approach to determine the phenomenon for each individual subject and for the entire group of subjects also- the interviewed decision makers. It may be extended as to determine a quotient for all 7 chapters and for all subjects, and a unique variation law of the whole phenomena found in the 7 chapters for all decision makers interviewed subjects.

Conclusions

Ambiguous organizational stress is defined in certain literature through the hundreds of elaborate definitions is as a phenomenon often analyzed. In terms of organization, there are two types of stress: direct- consequence of reducing the number of considered alternatives, less systematic analysis of alternatives, confusion in decision-making; and indirect- appearance of delays, absenteeism, accidents, negative moods in terms of communication.

Our pilot research study confirmed the hypothesis of the existence of stress factors that contribute to the deterioration of the situation of the sector concerned. After analyzing in mathematical manner it was observed the continuous regression to satisfaction makers – the group that has not sought and does not have its own tools and institutional support in solving and improvement actions. The solutions can be applied on several levels. At personal level it is solved through self-knowledge, identification and awareness of the problems. Everyone can self-manage and priorities the various factors generating stress/dissatisfaction. At the organizational level appears the need to create a department, served by trained personnel, to identify, manage and improve these factors. The local community / society through coherent policies and strategies of the mining, energy, economy in general, social work, health, education, culture, must increase the quality of life of those in the mining sector and their families.

The mathematical approach presented in the paper, can be a tool, a scientific support of institutional factors in solving the problem of stress both for subjects/individual, the whole group of decision on some factor of stress or the whole phenomenon of stress work.

The trends obtained by mathematical approaches can be very useful in forecasting studies, in developing strategies and measures to prevent stress.

Acknowledgment

“This paper was co-financed from the European Social Fund, through the Sectorial Operational Program- Human Resources Development 2007-2013, project number POSDRU/1871/1.5/S/155605 entitled “Scientific excellence, knowledge and innovation through doctoral programs in priority domains”, beneficiary University of Petroșani”.

References

1. Anisman, H. (2014) An Introduction to Stress and Health, Sage Publications Ltd.

2. Băban, A. (1998) Stresul şi personalitatea, Editura Presa Universitară Clujeană, Cluj-Napoca.

3. Bodea, I. (2002). Importanţa abordării problemelor psihosociale din mediul de muncă, Program twinning RO-IB-99-CO-01 România — Suedia, Timişul de Sus, Romania.

4. Bodea, I., Bozdog, A.F. and Burdea, F. (2013), Stresul, factor de risc important pentru sănătatea şi securitatea în muncă la minele din Valea Jiului, Conference ”Jubiliară a Inspecţiei Muncii, Securitate și Sănătate în Muncă”, 21-23 Octomber 2013, Sibiu, Romania.

5. Boldea, I., Irimie, S., Filip, E. and Muntean, L. (2015), Stress Analysis of Issues in the Mining Area, Conference ”Jubiliară a Inspecţiei Muncii, Securitate și Sănătate în Muncă”, 19-21 October 2015, Timisoara, Romania

6. Cooper, C. L. and Marshall, J. (1976), ‘Occupational sources of stress: a review of the literature relating to coronary heart disease and mental ill health’, Journal of Occupational Psychology, 49, 11—28.

Publisher – Google Scholar

7. Cox, T. (1978) Stress, Macmillan, London.

8. Cox, T. and Griffiths, A. (2010), ‘Work-related stress: a theoretical perspective’, in Leka, S. and Houdmont, J. (eds), Occupational Health Psychology, Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford.

9. European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA). (2015a), European Survey of Enterprises on New and Emerging Risks (ESENER-2-2014) Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Available: <https://osha.europa.eu/en/surveys-and-statistics-osh/esener>. [1 October 2015].

10. European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA). (2015b), Healthy Workplaces Good Practice Awards 2014—2015. Managing stress and psychosocial risks at work, Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Available:

<https://osha.europa.eu/ro/tools-and-publications/publications/reports/healthy-workplaces-good-practice-awards-2014-2015

>.[1 October 2015].

11. European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA). (2014), Calculating the costs of work-related stress and psychosocial risks — A literature review, Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Available:

<https://osha.europa.eu/en/tools-and-publications/publications/literature_reviews/calculating-the-cost-of-work-related

-stress-and-psychosocial-risks>. [5 June 2015].

12. European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA). (2012), Management of psychosocial risks at work: An analysis of the findings of the European Survey of Enterprises on New and Emerging Risks (ESENER), Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Available: <https://osha.europa.eu/en/publications/reports/management-psychosocial-risks-esener/view>. [5 June 2015].

13. European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA). (2010), The European Survey of Enterprises on New and Emerging Risks (ESENER), Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Available: <https://osha.europa.eu/en/esener-enterprise-survey/enterprisesurvey-esener>. [5 June 2015].

14.European Commission 2014. Eurobarometer 398 ‘Working Conditions’. Available from: <http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/flash/fl_398_sum_en.pdf>. [7 September 2015].

15. Floru, R. (1974) Stresul psihic, Ştiinţifică Publishing, Bucharest.

16. French, J. R. P., Caplan, R. D. and Van Harrison, R. (1982) The mechanisms of job stress and strain, Wiley & Sons, New York.

17. Golu, M. (1981) Stresul psihic in Dicţionar de psihologie socială, Enciclopedică Publishing, Bucharest, pp. 235-236.

18. Health and Safety Executive UK (2009), How to tackle work-related stress. A guide for employers on making the Management Standards work, Available: <http://www.hse.gov.uk/pubns/indg430.pdf>. [8 September 2015].

19. Holt, R. (1982) ‘Occupational Stress’ in Goldberger, L. and Breznitz, S. (eds.), Handbook of stress. Theoretical and Clinical Aspects. The Free Press, New York, pp. 419-444.

20. Irimie, S., Muntean, L., Pricope, S. and Irimie, I. S. (2015), ‘Methodological aspects regarding the organizational stress analysis‘. ACTA Universitatis Cibiniensis – Technical Series. [Online]. 66 (1), 61—66, doi: 10.1515/aucts-2015-0028. [Retrieved 12 October 2015], Available: <http://www.degruyter.com/view/j/aucts.2015.66.issue-1/aucts-2015-0028/aucts-2015-0028.xml?format=INT>.

Publisher – Google Scholar

21. Kalimo, R., Lindström, K. and Smith, M. J. (1997), ‘Psychosocial approach in occupational stress’, in Salvendy, G. (ed.), Handbook of human factors and ergonomics, Wiley, New York.

22. Karasek, R. A. Jr. (1979) ‘Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: implications for job redesign’,Administrative Science Quarterly, 24, 285—308.

Publisher – Google Scholar

23. Lazarus, R. S. (1990) ‘Theory-based stress measurement’, Psychological Inquiry, 1, 3—13.

Publisher – Google Scholar

24. Lazarus, R. S. and Folkman, S. (1984) Stress, Appraisal and Coping, Springer Publishing, New York.

Google Scholar

25. Marica, L., Irimie, S. and Băleanu, V. (2015). ‘Aspects of Occupational Morbidity in the Mining Sector’, Procedia Economics and Finance, [Online]. 23, 146-151, Elsevier. ScienceDirect, doi:10.1016/S2212-5671(15)00368-8, [Retrieved August 24, 2015], Available:http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2212567115003688.

26. Pitas, J., Hajkr, J., Havlik, J., Machala, P., Motala, M., Novák, I. and Staníček, Z. (2012) National Standard Competences Of Project Management Version 3.2 — Web, ISBN 978-80-260-2325-8, Publishing Společnost pro projektové řízení, o. s., Brno.

27. Selye, H. (1956) The stress of life, McGraw-Hill, New York.

Google Scholar

28. Spielberger, C. D. (2010) Job Stress Survey. Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology. 1. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.