Introduction

Individuals or entreprising entities have been levied taxes over centuries by a sovereign power. The resources were always necessary to fill in the state treasury, even deeply back to the era where they were not called taxes yet. Citizens require high quality of public services financed by the capital obtained from tax collection. Governments provide public services which companies in the market do not provide, because they are not economical for them, such as building roads, providing health care, ensuring legal system, security for the people, and education for the people. To fund public expenditures requires a lot of capital, and people would not be ready to contribute and pay for these services when they are needed, so the states impose various fees and taxes. However, there has always been unwillingness to pay taxes or various fees. Tax evasion represents a serious problem of each economy. It has a negative effect on the state budget and especially on public finances. Tax evasion is a threat to the society, the states and international organizations have been making an effort to combat negative phenomena associated with taxation, the tax evasion or tax fraud. Tax havens may be used for production activities but a more frequent use of theirs is to attract, with their tax systems especially mobil capital, e.g. bank deposits and intellectual property, insurance business and businesses where the mobil capital is crucial.

What is the reason why taxpayers are constantly looking for new ways to avoid taxation or at least to reduce the amount of tax liability? The world is full of news that big corporations do not pay taxes but people who work hard every day, their tax is immediately withheld from their salary. Many ask why this cannot be done also to big corporations. They do not consider current tax system fair. Nowadays, transparency where the money from the taxpayers goes is the highest priority.

Objectives and Methodology

The research object of the submitted paper is the concept of a tax evasion that must be tackled and combatted. The primary goal of the paper is to focus on the connotation of the basic terms related to the tax evasions, to study in details their characteristics and definitions, and to the factors influencing remarkably the occurrence of these phenomena. This scientific paper focuses on the tax evasion evolution, defining categories of the phenomena in this area sometimes resulting in tax fraud occurence. In addition, the strategies to detect potential tax evasion are highlighted to demonstrate governments’ efforts worldwide, their being keen on stopping or minimising negative consequences of tax frauds. Comparison, analysis and synthesis, and deduction as scientific methods were applied. There is no doubt that whenever business environment is analysed or evaluated, tax system of the state should not be ignored. What strategies are implemented to protect state budget before the tax losses, in the practical level, and the analysis of selected countries – Slovakia, the Czech Republic, Hungary and Bulgaria were studied and analysed and empirical results are presented covering 2 recent years 2014 and 2016. The data of this economic crime started to be collected only recently therefore, some data were obtained from the OECD database and from the research data of the auditing company PriceWatersCoopers, etc. There are no doubts about the negative impacts of tax fraud and tax evasion on the national budgets. The countries and international organizations strive to combat the tax evasion or tax fraud; these issues are the main challenges of international tax agenda worldwide. Speculative businessmen could be found everywhere. Moreover, the partial, illustrative empirical research using the information from databases of big auditing commpanies is proving the relevance of tax issues that should be solved with no deferral.

Literature Review

Tax evasion is a very old idea. The oldest evidences that confirm the existence of tax evasion are tax mutinies, which were first reported by ancient historians. The economic theory of a tax evasion is not as old as the phenomenon itself. According to Sandmo (2005), the beginning of the theoretical concept of tax evasion from the perspective of practitioners’ experience and theoreticians’ ideas can be dated to 1972. In that year, the first scientific paper about tax evasion was published, “Income Tax Evasion: A Theoretical Analysis” by Allingham and Sandmo. Tax evasion is defined by The European Commission as a phenomenon which “generally comprises illegal arrangements where tax liability is hidden or ignored, i.e. the taxpayer pays less tax than he/she is supposed to pay under the law by hiding income or information from the tax authorities”. (EC – Taxation and Customs Union, 2017). Nowadays, a large number of domestic and foreign literature exists which deals with the topic of tax evasion and tax fraud. (Hayoz and Hug, 2007), (Gravelle, 2015), (Brown, 2011), (Tooma, 2008), (Murray, 2012). According to Webley et al. (2010), it is an old, but a constantly developing issue. Beck, Lin and Ma (2014) are looking for the answer to the question: Why are companies constantly trying to avoid taxing? Other researchers are looking for new ways to reduce (Alm, 2012), (Piolatto, 2014) and measure tax evasion (Mo, 2013). There is an effort to compile different models for measuring, and analysing tax evasion by applying various factors (Spicer, 1986), (Xiao, Liu and Lai, 2014), (Seidel a Thum, 2016). Thakur (2013) describes how to detect tax evasion by shares and how to catch fraudsters. Mawejje and Okunu (2016) examine the interaction between different indicators of the current business environment and tax evasion. Li and Ma (2015) focus on the relationship between the government and tax evasion.

The term of tax evasion is often used by the public or in the academic environment, but to find its general definition is difficult. Faltová (2015) found out that the common element of all definition of tax evasion was the illegality. Aleš (2000) writes that tax evasion is a failure of tax liability. The concept of tax evasion (Boháč, 2015) can be understood as a situation in which the tax is not determined in accordance with the law. The result of mentioned situation is a difference between the amount of tax payable and the amount of tax paid. The amount of tax paid by the taxpayer is lower than the amount stated by the law. On the other hand, Lenártová (2000) defines tax evasion as a result of targeted, legal or illegal, economic behaviour of a taxpayer, which leads to the reduction or elimination of tax liability or to other economic benefit resulting from taxes.

Foreign literature uses terms of “Tax evasion” and “Tax avoidance” associated with this context. Experts characterize “tax evasion” as a type of tax fraud activities for which taxable entity can be sanctioned. The form of a sanction depends on the extent of tax reduction, the amount of tax not paid and whether or not the intention of tax elimination was demonstrated. Tax evasion can also occur based on ordinary ignorance, lack of information or negligence. The constantly changing tax laws and regulations contribute to the disruption of legal certainty and to unintentional misconduct of the taxpayer.

Tax evasion and tax avoidance

The topic of tax evasion is a very actual problem of our society. People and organizations all over the world strive to find methods for detecting and reducing tax evasions. The crucial question frequently raised is what tax evasion means and what a variety of tax evasion cases may exist. Tax evasion is characterized as the result of the economic behaviour of taxpayers, considered as a leakage of tax liability. Tax avoidance is considered as a legal tax optimization, when a taxable entity applies all legal provisions to minimize the amount of his tax liability. It is actually a tax evasion while the taxable person uses all the legal options. The taxable entity can apply all statutory exceptions, exemptions, tax reliefs, discounts, depreciation, joint taxation of husband and wife, standard or percentage expenses of income and reserves directly and intentionally settled in the legislation. Legal tax optimization can include the usage of gaps in law and regulations. (Faltová, 2015)

To tackle international tax avoidance, it is necessary to take into consideration that most double tax treaties are bilateral. A common form of abuse of treaties is “treaty shopping”. OECD defines treaty shopping as an analysis of treaty tax provision to structure an international transaction or operation to take an advantage of a particular treaty. Treaty shopping is the improper use of treaties and it may be applied to a sitution where a person, not resident in either of the treaty countries, establishes an entity in one of the treaty countries to obtain treaty benefits. Treaty shopping usually covers also the process of setting up a special purpose vehicle (100 percent-owned subsidiary) which is tax resident in one of the Contracting states. This special purpose vehicle will receive income at reduced rates of witholding tax under the targeted treaty, and then it is passed to the owner of special purpose vehicle. (Miller, 2017, p.492). For instance, Slovak company Ltd. is a resident in tax haven country Delaware that does not have a tax treaty with the country of ZZ. Complying with ZZ’s domestic law, ZZ levies a witholding tax of 25% on interest and royalty fees to non-residents, but it levies no witholding tax on interest paid to residents of DD. Following the terms of the tax treaty between ZZ and DD, if Slovak entity Ltd. invests $1 million in interest bearing securities in ZZ and earns $100,000 interest, at the time when the interest is paid, the interest will be a subject to a 25% witholding tax. It is not probable that Slovak entity Ltd. could claim double tax relief for the witholding tax in Delaware, as Delaware, being a tax haven, would not levy Slovak entity Ltd. much, if any tax.

The leak in law and regulation is, for example, the case of dividing a trading company into smaller business units makes it is possible to avoid a higher tax rate if progressive taxation is applied. “Schwarz system” is another way to achieve legal tax benefits. Schwarz system means hiring workers based on their business license instead of employment contract. (Faltová, 2015).

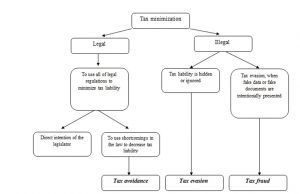

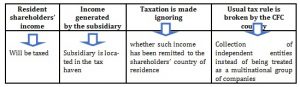

Illustration 1: The types of tax minimization

Source: Processed by the authors

On behalf of the Ministry of Finance of the Czech Republic, Krestesová and Rezek (2013) drew up a scheme which helps to explain inconsistencies in the definitions of the terms in connection with tax evasion. The scheme showed and explained the terms used only in Slovak and Czech terminology and did not take into account the definitions presented by experts around the world. The new schema prepared by the authors of this paper shows different perspectives on the definition of tax minimization. The European Commission (EC – Taxation and Customs Union, 2017) clarified the concepts of the three most important phenomena that form the basis of our topic:

- Tax Fraud – “is a form of deliberate evasion of tax which is generally punishable under criminal law. The term includes situations in which deliberately false statements are submitted or fake documents are produced”

- Tax Evasion – “generally comprises illegal arrangements where tax liability is hidden or ignored, i.e. the taxpayer pays less tax than he/she is supposed to pay under the law by hiding income or information from the tax authorities”

- Tax Avoidance – “is defined as acting within the law, sometimes at the edge of legality, to minimise or eliminate tax that would otherwise be legally owed. It often involves exploiting the strict letter of the law, loopholes and mismatches to obtain a tax advantage that was not originally intended by the legislation”.

Determinants of Tax Evasion

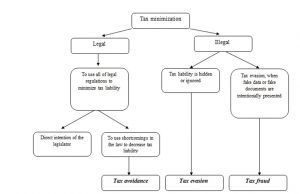

Tax evasion is the phenomenon affected by a number of different factors due to globalization. Ciupek (2015), in her publication, describes the causes of tax evasion from income tax liability, in six areas representing d(see illustration 2):

Illustration 2: Tax Evasion Determinants

Adapted from Ciupek (2015, p. 84)

Globalisation has an incredible impact on all determinants (see below) and through them it has been affecting the entrepreneurs in making decisions related to tax evasion phenomena

- Economic factors – financial and economic situation of a taxable entity, general business conditions, the amount of tax burden, the probability of the detection of tax evasion, the amount of sanctions, and business stagnation.

- Legal factors – distrust in the state and in public institutions, freedom to influence the actual status of economic events, burdensome nature of recording responsibilities, complexity and inconsistency of tax regulations.

- Social factors – exchange-related justice connected with tax payments and tax benefits, horizontal, vertical and procedural justice.

- Demographic factors – age, gender, education, and marital status.

- Mental factors – sense of nationality, patriotism, place of tax residence, attitude to legal standards.

- Moral factors – attitude to civil obligations, and attitude to taxation, ethics, religion, habit.

Lenártová (2000), in her scientific paper, also examines the determinants of tax evasion, where she lists the following group of factors: economic, legal, socio-political, tax-technical, psychological, ethical and social factors.

Both researchers Ciupek (2015) and Lenartova (2000) identified that the reason for tax evasions are financial and economic situation of the state, and the amount of tax burden levied on the sole proprietors and corporations. After the financial crisis in 2008, a lot of countries in the European Union struggled to achieve any economic growth, governments in the CEE block wanted (belonging to the developing countries or in transition towards developed contries) to attract investors and FDI to support development and economic growth also by attractive tax rates. Simple generalisation offers the idea of researching the countries that have a common historical development bacground (Austrian –Hungarian monarchy) (Czech Republik, Slovakia and Hungary were the parts of the monarchy), or they shared also a communist historical period, after the 2nd world war till 1989 and we assumed common mental and moral factors. Attitude to civil obligations and attitude to taxation for these states would be similar and we have also selected the state Bulgaria with the lowest tax rates, and another criterion of the choice that rates should be around the average of the EU (around 20%), what is sufficiently low and the enterprising community should be assumed to pay taxes and tax fraud should not be a threat for them. That was not completely in accordance with our assumption because Hungarians show the highest percentage of tax fraud and the tax rates are low, since 2016 corporate tax rate is 9%, the lowest one in the CEE.The trend in corporate tax rates has been stagnating or declining, except for Slovenia. Slovenia has the highest personal tax rates, from 41% tax rate increased to 50% and is unchanged since 2014. Slovakia has the highest corporate tax rate in our selected sample, but still the below EU average tax rate which is 21,3%.

Table 1: Development trend in tax rates in selected countries of the CEE

Legend: Slovakia* for the sole proprietors (over 34000 EUR the tax rate is 25%.)

Czech republic: an additional tax of 7% is to be paid from the income from independent activity and employment, if the total income (in case of employment) or tax base (in case of self-employment) exceeds CZK 1,438,992 (approx. EUR 56,343). The tax is paid only from the surplus.

Soures: Adapted from the resource (Income tax rates, 2018)

Tax Fraud in selected countries of the Central and Eastern Europe

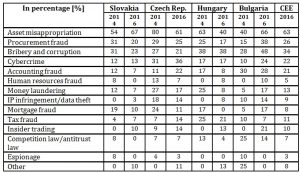

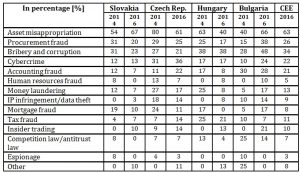

Price waterhouse Coopers examined economic crime in the countries around the world. Table 1 shows that tax fraud in the analysed countries reaches higher results than in the global environment. The number of respondents in Slovakia who had registered tax fraud in their environments in 2016 (11%) was higher by 75% than in 2014 (4%). This number in the Czech Republic is much higher than in Slovakia. According to respondents, the appearance of tax fraud in the Czech Republic from 2014 to 2016 increased by 100%. While Slovakia and the Czech Republic record an increase in the number of tax fraud cases, Hungary and Bulgaria registered a decline. In 2014, the number of respondents in Hungary who registered tax fraud in their environment during the analysed period was 25%. In 2016 it was only 21%. A decrease has also been noticed in Bulgaria, where the amount declined from 10% to 7%. In 2016, Slovakia (7%) and Bulgaria (7%) showed lower values of tax fraud appearance than the CEE average (11%), while the survey’s results in Hungary (21%) and the Czech Republic (14%) exceed the CEE average. This information started to be collected recently; the simple comparison of selected countries and the CEE is conducted with the prospects for a deeper research.

Table 2: Tax Fraud as Economic Crime: Slovakia, Czech Republic, Hungary,

Bulgaria and the CEE

Source: Own elaboration based on (PwC, 2014-2016)

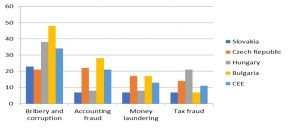

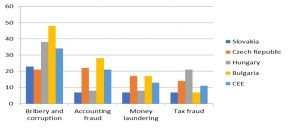

Illustration 3 compares the appearance of tax fraud and related economic crimes in Slovakia, the Czech Republic, Hungary and Bulgaria in 2014. Bribery and corruption were in the first place. In all the analysed countries, more than 25% of respondents met this type of economic crime in their business environment during the analysed period.

Illustration 3: Economic Crime in 2014

Source: Own elaboration based on (PwC, 2014b), (PwC, 2014c), (PwC, 2014d) and (PwC, 2014e)

Hungary reported much higher results as other countries – 38%. Slovakia and the Czech Republic showed the same level of accounting fraud occurance. This type of economic crime was the highest (30%) in Bulgaria. Money laundering was the most common in the Czech Republic and Hungary, while in tax fraud Hungary outran all the other analysed countries.

Illustration 4 compares the appearance of tax fraud and related economic crimes in Slovakia, the Czech Republic, Hungary and Bulgaria in 2016. Bribery and corruption were still in the first place. Slovakia and the Czech Republic had the lowest level of corruption, Hungary reported similar results as the CEE average. Bulgari’´s survey results transcend values in analysed countries. Slovakia and Hungary were on the same level in the occurrence of accounting fraud. This type of economic crime was the highest (30%) in Bulgaria, higher than the CEE average (21%). Money laundering was the most common in the Czech Republic and Bulgaria, while in tax fraud, Hungary still outran all the other analysed countries.

Illustration 4: Economic Crime in 2016

Source: Own elaboration based on (PwC, 2016 a-e)

Bribery and corruption are very frequently defined as abuses of power by people in positions of authority. They’re still going strong: it’s estimated that more than US$1 trillion is paid each year in bribes, globally, and that US$2.6 trillion is lost to corruption. That’s 5% of global GDP – and the true figure is probably even higher, (PwC, 2016). Politicians in many countries with their political scandals related to the economic crime do not motivate businesses to behave ethically, but by this, they push away honest investors who look for stability and sustainability. If politicians cover the accounting or tax fraud because they may be involved as well, the public and ethical businesses have the only chance to start fighting against these negative phenomena, and support and elect people who are moral and ethical and can really protect taxpayer’s capital resources by accepting a suitable laws and legislation. The health business environment plays an important role for entrepreneurialship and in combatting negative phenomena such as economic crime, fraud, and absence of law enforcement, etc. (Peracek, Noskova and Mucha, 2017). What steps have already been executed or strategically planned to combat; e.g. tax evasions, is explained in the following paragraph.

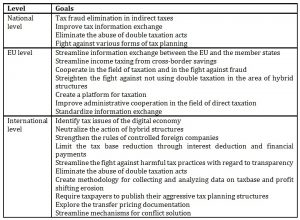

Objectives and Strategies of Combatting Tax Evasion

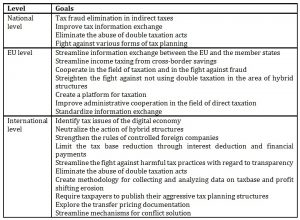

Tax evasion limits countries in the implementation of their economic policy. It also represents a problem from the justice’s perspective. Countries, states, as well as the European Union, try to combat this phenomenon, analyse its range and to accept necessary actions to detect tax evasion and reduce the leakage. The biggest problem is that the evolution of tax evasion is faster than the actual regulation of legislation. The fight against tax evasion is undoubtedly a very actual, complex and sensitive issue at the same time. The goals of this fight are the efficient tax collection with unchanged tax rates, to discourage taxpayers from illegal actions and from using tax optimalization. The fight against tax evasion involves individual states, the European Union, as well as other international organizations. It can be successful only if all states and organizations join their forces and fight together against fraudsters. Actions to combat tax evasion are implemented at three levels: national level, EU level and international level. (Huba, Sábo and Štrkolec, 2016)

Table 2: Goals of the fight against tax evasion at national, EU and international level

Source: Own elaboration based on (Huba, Sábo and Štrkolec, 2016)

States and countries worldwide have recognized the need of the taking actions to combat tax evasion. These actions can be divided into two groups. The first group is created by the actions that have developed within the decision-making process of the general courts and they have the nature of criteria. These criteria are marked as tax doctrines. The second group is characterized as actions that have been adopted under an individual legislation. General anti avoidance rule (GAAR) has been introduced as a statutory action designed for the fight against tax evasion. It is defined as a set of rules based on individual general principles existing in the national tax rules and which are modeled to combat tax evasion. GAAR is a concept in the tax code which allows the tax authorities to deny taxpayers the right to recognize tax advantage. The goal of GAAR is also to penalize actions and transactions that may create a situation of illegal tax evasion. GAAR has been introduced as a statutory action designed for the fight against tax evasion, (Sábo, 2015). Generally, strategies to detect aggressive tax planning schemes can be divided into 5 main categories:

- Disclosure and Reporting – taxpayers or third parties provide relevant information to the tax authorities. Initiatives proved to be useful for this strategy, are special reporting obligation on losses, manadatory disclosure rules, ruling and co-operative compliance programs.

- Investigations and audits – the tax administration itself seeks to detect relevant information by using its investigative powers.

- Domestic and international cooperation – strategies that seek to build on information held either by government departments or that involve co-operation with the tax administration of another country.

- Data analysis – strategies that seek to make the best use of internal tax administration information or external public data. The success of data analysis is dependant on the volume and quality of data available to the tax administration and how good they are at analysing, comparing, processing data and interpreting the information obtained to produce meaningful results.

- Other detection strategies

Participating countries that have developed business models aimed at improving tax risk management and compliance by large business taxpayers through greater cooperation in Australia, Ireland, Italy, The Netherlands, New Zealand, Spain, Sweden, The United Kingdom and the USA, (OECD, 2016).

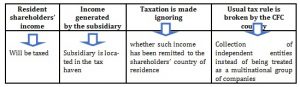

Novackova (2017) and her team studied tax havens and they state that tax havens are a big attraction for multinational companies to be utilised as international tax planning scheme, therefore, they are in the focus of government tax policy initiatives. (Milosovicova, Novackova a Wefersova, 2017). Anti-haven legislation is introduced in many countries to protect their domestic tax base. There are some means how to control abusing tax haven for this purpose: such as a) pressure from supranational bodies for example the OECD, the EU threatens tax havens by imposing economic and trade sanctions on them; b) transfer pricing rules – they do not apply to arm’s-length transactions, therefore, not all forms of haven abuse are tackled, c) company residence rules- governments have been failing over years to define adequately entity’s residence for tax purposes which caused that the tax haven abuse may be exercised, d) controlled foreign companies (CFC) legislation – the most effective method of eliminating deferral. The term “controlled foreign company” is used only in the meaning of a subsidiary resident in a country where it pays little or no tax. “Domestic shareholders of foreign companies must pay tax currently on their pro rate share of the income of the foreign company. Timing of the liability for domestic tax from the time of distribution of the foreign company’s profits to its shareholders to the time at which it is derived by the foreign company is affected by CFC legislation. This legislation aims at bringing the timing forward.” (Miller, Oats, 2016, p.567). How controlled foreign companies’ CFC legislation is applied by the national government to a resident taxpayer is explained in the following scheme

Table 3: CFC legislation

Source: processed by authors

Miller and Oats (2016) state that if the CFC legislation is applied to a resident taxpayer by a government, the tax is levied on the tax resident taxpayer as if the income had been earned by that tax payer.

25 years ago, this American company, which owns 100% owned subsidiary in Anquilla, invented a patent for the mining industry. At that time, the owners did not assume a real value of this intangibility. The US company transferred the ownership title to Anquilla subsidiary for a minimal amout of USD. After years, it has become a successful invention and it is licensed in the countries worldwide, earning the company a huge amount of royalties. The US is not able to tax the subsidiary on the royalty revenues not being resident in the USA and without any source of income in the USA. But government can impose the tax on the US company as if the US company received the royalties (which were received by the subsidiary). The company is taxed on all the income generated by this subsidiary, albeit the US company has received any dividend or interest from the Subsidiary in Anquilla. The application of CFC legislation prevents the US company to defer tax on the Anquila income until a dividend orinterest is paid by Anquilla subsidiary. Because this deferral could be even indefinite, (that means that no payment was ever given to the USA from this Anquilla’s income collected).

Figure 1: US company with 100% owned subsidiary in Cayman Islands

Source: Adapted by the authors based on the (Miller, Oats, 2016)

CFC legislation is usually focused on the resident shareholders’ passive income of the foreign subsidiary (i.e. not on the trading earnings) with the purpose of taxing it. Passive income is derived from the financial investments and these are more likely to be transferred to the foreign subsidiary where they are taxed by the lower tax rate. It is a preferential treatment to transferring operations or business. The important arguments of advocates for relocating financial investments are two crucial points: price and complicated process of relocation, which is cheaper and less complicated compared to relocating factories and labour force.

Conclusion

While state authorities are trying to find a way to capture fraud and to adapt it to the legislation, tax entities already use new legal and illegal methods to avoid paying. Countries invest a lot of effort into intercepting tax evasion and tax fraud. Nevertheless, it is almost impossible to determine their size. PwC, in its surveys, has determined the size of the part that tax fraud presents in economic crimes. Analysis contains information about tax fraud as a part of economic crime from the global perspective, in Slovakia, Hungary, the Czech Republic and Bulgaria. According to the PwC survey, the highest tax fraud in the selected countries has been measured in Hungary. This area represents a large area of future research, an opportunity to consider the reasons of the phenomenon and how to fight against it.

Governmental and public concern over the tax practises of multinational gigants led to strenghtening the fight against the tax evasions and fraud. Especially that NGOs are very active to push introduction of country by country financial reporting made by multinationals businesses (MNEs), especially disclosing earnings made and tax paid in each country where the MNEs do business. There are many aspects still not examined in this area of taxation and great opportunities for doing the research which, we all hope, will bring real successful results in combatting the tax crimes.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

References

- Aleš, J. (2000) ‘Daňový únik,’ Právo a podnikaní, 22.

- Alm, J. (2012), Designing alternative strategies to reduce tax evasion, Tax Evasion and the Shadow Economy, Pickhardt, M. and Prinz, A. (ed.) Edward Elgar Publishing, Inc., Massachusetts, USA.

- Beck, T., Lin, C. and Ma, Y. (2014), ‘Why Do Firms Evade Taxes? The Role of Information Sharing and Financial Sector Outreach,’. The Journal of Finance 69, 763-817.

- Boháč, R. (2015), Teoretické otázky českého daňového práva z hlediska daňových úniků a podvodů, Daňové právo vs. daňové podvody a daňové úniky, Babčák, V., Románová. A. and Vojníková, I. (ed.) Vol. 1. Univerzita Pavla Jozefa Šafárika v Košiciach, Košice.

- Brown, K. B. (2011), A Comparative Look at Regulation of Corporate Tax Avoidance: An Overview, A Comparative Look at Regulation of Corporate Tax Avoidance, Brown, K. B. (ed.) Springer, New York.

- Ciupek, B. (2015). Premises of the phenomenon of income tax evasion, Daňové právo vs. daňové podvody a daňové úniky, Babčák, V., Románová. A. and Vojníková, I. (ed.) Vol. 1. Univerzita Pavla Jozefa Šafárika v Košiciach, Košice:

- Faltová, Š. (2015), Daňový únik, Daňové právo vs. daňové podvody a daňové úniky, Babčák, V., Románová. A. and Vojníková, I. (ed.) Vol. 1. Univerzita Pavla Jozefa Šafárika v Košiciach, Košice.

- Gravelle, J.. G. (2015), ‘Tax Havens: International Tax Avoidance and Evasion,’ [Online], [Retrieved January 1, 2017], https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R40623.pdf

- Hayoz, N. and Hug, S., (ed.). (2007) Tax evasion, Trust and state capacities, Peter Lang AG, Germany.

- Huba, P., Sabo, J. and Štrkolec, M. (2016), Medzinárodné daňové úniky a metódy ich predchádzania, Univerzita Pavla Jozefa Šafárika v Košiciach, Košice.

- Kajanová, J. (2015), ‘Vývoj priamych daní na Slovensku’, Maneko, 2015,VII (1), 17-26.

- Krestesová, M. and Rezek, V. (2013), ‘Daňové nedoplatky a daňové úniky,’ [Online], [Retrieved January 2, 2017], http://www.mfcr.cz/assets/cs/media/2013-10_Danove-nedoplatky-a-danove-uniky.pdf

- Lenártová, G. (2000), ‘Faktory vzniku daňových únikov’. Ekonomické rozhľady, 243.

- Li, L. and Ma, G. (2015), ‘Government Size and Tax Evasion: Evidence from China,’ Pacific Economic Review, 20 (2), 346-364.

- Mawejje, J. a Okumu, I. M. (2016), ‘Tax Evasion and the Business Environment in Uganda,’ South African Journal of Economics 84 (3), 440-460.

- Miller, A. and Oats, L. (2016) Principles of International Taxation, 5th ed. Bloomsburry publishing, West Sussex, UK.

- Milosovicova P., Novackova D., and Wefersova. J. (2017) Medzinarodne ekonomicke pravo. 1. vyd. – Praha : Wolters Kluwer, Czech Republic, S.282

- Mo, P. L. L. (2003) Tax Avoidance and Anti-Avoidance Measures in Major Developing Economies, Praeger Publishers, USA.

- Murray, R. (2012), Tax Avoidance, Sweet&Maxwell, London, UK.

- Ölvecká, V. (2016). The analysis of tax licence consequences on global business environment. Glo-balization and Its Socio-Economic Consequences: International Scientific Conference: University of Žilina, 2016 (vol 4), pp. 1604-1612, [Online], [Retrieved March 1, 2017] http://ke.uniza.sk/sites/default/files/content_files/proceedings_part_iv.pdf

- Sabo, J. (2015), GAAR (všeobecné pravidlo predchádzania daňovým únikom) v právnom poriadku SR, Daňové právo vs. daňové podvody a daňové úniky, Babčák, V., Románová. A. and Vojníková, I. (ed.) Vol. 2. Univerzita Pavla Jozefa Šafárika v Košiciach, Košice.

- Sandmo, A. (2005) ‘The Theory of Tax Evasion: A Retrospective View,’ National Tax Journal, 58 (4), 643-663.

- Peráček, T., Nosková, M. and Mucha, B. (2017) Selected issues of Slovak business environment, Economic and social development-“Managerial issues in modern business” (Book of Proceedings) Varazdin: Varazdin development and entrepreneurship agency, pp. 254-259.

- Thakur, P. K. (2013) Tax Evasion Through Shares, Prashant Kumar Thakur at Smashwords, Kolkata.

- Tooma, R. A. (2008) Legislating Against Tax Avoidance, IBFD, The Netherlands.

- Webley, P., et al. (2010) Tax Evasion: An Experimental Approach, Cambridge University Press, New York, USA.

- EC – Taxation and Customs Union. (2017) ‘The fight against tax fraud and tax evasion – Time to get the missing part back’. [Online], [Retrieved January 9, 2017], https://ec.europa.eu/taxation_customs/fight-against-tax-fraud-tax-evasion/missing-part_en

- Income Tax rate 1995-2016. Trading Economies. online.[Online], [Retrieved March 16, 2016]. Available at: http://www.tradingeconomics.com/denmark/indicators