Introduction

Within the context of the Europe 2020 strategy, a set of integrated guidelines for economic and employment policies was launched in April 2010, calling on EU Member States and social partners to set up ‘schemes to help recent graduates find initial employment or further education and training opportunities, including apprenticeships, and intervene rapidly when young people become unemployed’. In the same year, two Europe 2020 flagship initiatives were launched, namely, an ‘Agenda for new skills and jobs’ and ‘Youth on the move’. In 2012, a specific ‘Youth employment package‘ was launched, which led to an increased focus on providing quality traineeships and apprenticeships for young people and to calls for the introduction of a ‘Youth guarantee’, designed to ensure that all young people up to the age of 25 should receive a quality job offer, continued education, an apprenticeship or a traineeship within four months of leaving formal education or becoming unemployed. In 2013, the ‘Youth employment initiative’ was launched: it was designed to specifically support young people not in education, employment and training in regions where the youth unemployment rate was over 25 %.

One of the most important decisions in life concerns the choice of when to make the move from education to the world of work. The transition has, in recent years, become more prolonged and increasingly unpredictable, with young people switching jobs more frequently and taking longer to become established in the labour market, either by choice or necessity. It has also become increasingly common to find tertiary education students taking part-time or seasonal work to supplement their income, or for young people already in employment to seek a return to education and training in order to improve their qualifications mentioned by Alexe I. (2016) in his study.

Statistics for employment and unemployment have traditionally been used to describe labour markets, in other words, providing data on people who have a job and those who are actively looking for one. However, an analysis of the labour market participation of younger people is somewhat different, especially when:

- a large proportion of young people are still attending school, college, university, other higher education establishment or training, and;

- another group of young people are neither in employment (unemployed or economically inactive), nor in education or training (NEETs).

The share of young people neither in employment nor in education and training is an indicator that measures the proportion of a given subpopulation who are not employed and not involved in any further education or training; these people may be subdivided into those who are unemployed and those who are considered economically inactive.

An assessment of the level of socio-professional insertion of the young graduates, according to their specialization and qualification level, leads to a conclusion on the transition of young persons from the pupil/ student status to that of employee, the concordance between the supply and demand on the labor market, to conclusive information on the effectiveness of the educational act on all levels of the system. Both in Romania and in Bulgaria, the insertion of young graduates in the labor market is a problem that has grown in recent years as a result of restructuring in various fields of activity, economic development, the proliferation of new forms of employment, increase of unemployment among young persons, the prolongation of the study period, changes in the social protection system, migration to West Europe and geographic mobility, mentioned by Cretu (2018) and Iova (2018) in their studies.

As youth unemployment is a social problem with multiple implications in the two analyzed countries, facilitating the transition of young persons from study to the labor market must become a national priority. It was observed that the degree of insertion in the labor market depends on one hand on the graduates’ skills and aptitudes, his/her specialization and also his/her personality, the attitude towards work, the way of “selling” on the labor market, plus the concrete conditions, the opportunities, the general constraints of the labor market at some point when seeking for a job. Petroff (2016) and Zaharia (2016) in their books accept the idea that the integration of young persons on the labor market is a factor of economic growth with a major role in creating their economic welfare and social comfort with consequences in their further development.

Materials and Methods

The present study aims at identifying some opportunities for increasing the socio-professional insertion of young persons on the labor market in Bulgaria and Romania, starting from the fact that in both countries the statistics show that the number of young unemployed is increasing. In terms of employment and youth unemployment, the factors and characteristics of the labor market generally apply, but there are also specific issues for the two countries where young persons are one of the most disadvantaged groups because most employers prefer not to hire persons without experience and without work experience. In addition, a large proportion of young unemployed do not have qualifications and specialties, requested by the labor market, making it more difficult for them to enter the labor market. From this perspective, the present study is a qualitative research, which is based on an analysis of the specialized literature, but also on the interpretation of quantitative data derived from the analysis of statistical information, compared in evolution between the two countries.

As research methods, we used documentation, analysis and data processing from a secondary analysis. These methods are based on the processes of synthesis, induction and deduction, analogy and comparative analysis. Once the information has been defined, known and interpreted, the next step was the detailed documentation of the field of interest. In the analysis, the study of the available documentation for the field or for the analyzed system is a starting point for obtaining the first knowledge and information.

The documentation also involves the analysis of legislation and the comparative analysis of different specialized sources. Documenting, analyzing and processing of data and information from the following sources: the data and public information made available by the National Institute of Statistics, under the form of series of time that characterize the dynamics of the labour force and at the employment level; the data and information reported by Romania to the European Commission, as a member state of the European Union and are available in the public database of the European Institute of Statistics EUROSTAT; Europe 2020 Strategy; the National Employment Strategy 2013-2020, analyzed comparatively for the two countries; the National Institute of Statistics of Romania and Bulgaria; scientific works in the field; sites with specialized studies; Specialty literature.

Results and Discussions

The issue on the young graduates insertion on the labor market is present not only in Romania and Bulgaria, but the unemployment rate in Europe is much higher as unemployment rate in the USA. The desired labor force must be highly satisfactory and skilled, flexible and efficient, stable and loyal. The supply is influenced by the factors such as education system, vocational training, social area, even the family. In recent years, the economies of the European countries to which the economy of Romania and Bulgaria align, have been affected by profound changes. In this context, employers, in their desire to remain competitive, have an obligation to adapt to new technologies and organizational methods, mentioned by Prisacariu (2016) and Vlad (2015) in their studies.

At the same time, employees must also adapt to these changes by acquiring permanently new skills needed to use new technologies. In 2017, the active population in Romania was 9,120 thousand persons, of which 8,671 thousand employed and 449 thousand unemployed. In year 2017, the population employment rate aged 20‐64 years old was of 68.8%, at a distance of 1.2 percent points compared to the national target of 70% established in the context of Europe 2020 Strategy.

By age and gender, the female population was 15-24 years old, respectively 65 years of age and over, the largest deficit of inactive people. The female population aged 35-44 and 45-54 is the most active in the labor market .

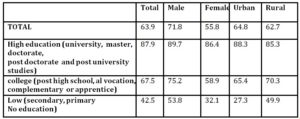

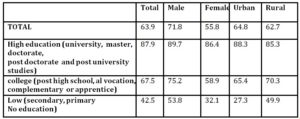

In 2017,the employment rate of active population aged (15‐64 years old) was 63.9%, increasing compared to the previous year by 2.3 percent points. As during the previous years, the employment rate was higher for men (71.8%, compared to 55.8% for women). On residence areas, the employment rate was higher in the urban area (64.8%, compared to 62.7% in the rural area).

The employees, increasing compared to the previous year (+189 thousand persons), held further on the highest share (73.7%) of total employed population. In 2017 the self-employed and not remunerated family workers represented 25.3% of the employed population. The workers qualified in agriculture, forestry and fishery represented 19.2% of the total employed population. The significant shares in the total employed population held also qualified workers (16.9%), specialists in various sectors of activity (15.4%) and workers in the services sector (14.8%).

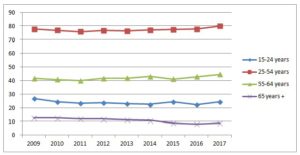

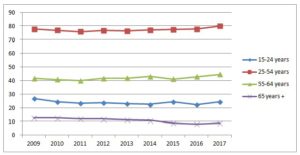

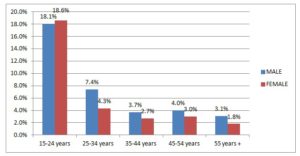

The male active population on the labor market records an increase in the 15-24 age group compared to the female population of the same category and a decrease in the occupied population in the age group of 65 and over. The most active male age categories on the labor market are those aged 35-44 and 45-54 respectively, as is the case for women. The employment rate of young persons (15-24 years old) was 24.5% and that of the old persons (55-64 years) of 44.5%. (Figure. 1).

Figure 1: Evolution of employment rate of 15 years old and over, on age groups, in Romania

The employment rate of the working age population (15-64 years) was 63.9%. This indicator had higher values for men (69.7% compared to 53.3% for women) and values closer to the two residence areas (62.6% in the urban area and 60.2% in the rural area). The highest level of employment rate for older workers was recorded among graduates of higher education (87.9%). 67.5% of persons with college education were employed and 42.5% of those with low education. (Table 1.). Higher values were recorded for the masculine population (71.8% compared to only 55.8% for the feminine population) and for the urban population (64.8% compared to 62.7% for the persons in the rural area).

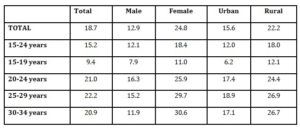

Table 1 :Employment rate of working population according to level of education, gender and areas, in 2017, in Romania- %

The analysis according to level of training reflects the fact that the employment rate of older workers (15-64 years) with higher education level was 87.9%. By sex, the employment rate of men with higher education exceeded by 3.3 percentage points that of women with the same level of education, and by areas, there were +3.0 percentage points in favor of persons in urban area, compared to rural area. 67.5% of persons with college education were employed, with differences between sexes (14.2 percentage points in favor of men) and between residence areas (4.9 points more for persons in rural area compared to urban area). With low level education, only 42.5% were employed, in this case the highest discrepancy (21.7 percentage points) was recorded by gender: for women, the employment rate was only 32.1 %, compared to 53.8% for the men.

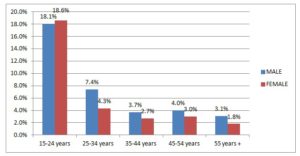

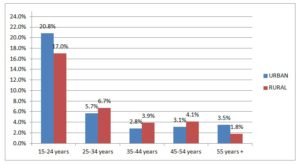

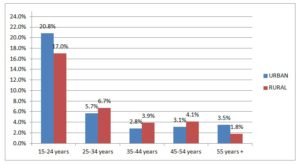

The unemployment rate was of 4.9%, decreasing compared to the previous year (5.9% in 2016). On gender, the difference between the two unemployment rates was of 1.6 percent points (5.6% for men compared to 4.0% for women) (Figure 2), and on residence areas of 0.9 percent points (5.4% in the rural area compared to 4.5% in the urban area) (Figure 3). The unemployment rate had the highest level (18.3%) among the young (15‐24 years old).

Figure 2: Unemployment rate on gender and age groups, in 2017, in Romania

Figure 3: Unemployment rate on age groups and areas, in 2017, in Romania

The unemployment was affected to a great extent by the graduates of primary and medium education, for which the unemployment rate was of 6.8%, respectively 5.1%. The unemployment rate was of only 2.4% in the case of the high education persons. The long term unemployment rate (one year and over) was of 2.0%, and the long term unemployment (share of the persons who are unemployed of one year and over of total unemployed) was of 41.4%. For the young (15‐24 years old), the long term unemployment rate (6 months and over unemployment) was of 11.1%, and the long term unemployment among the young of 60.4%.

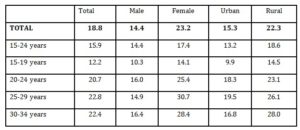

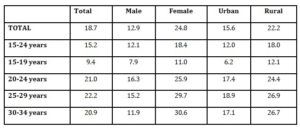

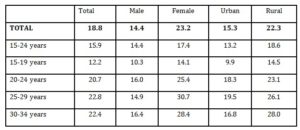

In Romania, in 2017, the employment rate of the population aged 20-64 was 66.3%, at a distance of 1.2 points from the national target of 70% set in the context of the Europe 2020 Strategy. The rate of unemployed young persons who do not attend any form of education or training (calculated for the 15-24 age group) was 15.2% in 2017, higher for women (18.4% compared to 12.1% for men) and in the case of residents in rural area (18.0% compared to 12.0% for young persons in urban area) (Table 2.).

Table 2: Unemployed young rate who do not attend any form of education or training in 2017, in Romania-%

By 2020 – the period of implementation of the updated Employment Strategy 2013-2020 in Bulgaria, some threats can improve the correlation between labor supply and supply and the functioning of the labor market: the slower exit from the recession and low economic growth in the EU and the slow recovery of the economy in Bulgaria, which, together with the insufficient competitiveness of the economy, threaten to create more and better jobs; Globalization, which hides the risks of job reduction, economic activity and loss of income for certain professions, regions and industries; unfavorable demographic trends – by reducing the number and aging of the labor force, which limits job supply; Deterioration of the quality of the labor force due to the emergence of highly qualified labor force and access to low-skilled and low-education persons; External migration processes, as well as delays in the quality and adequacy of education, low participation of the population in lifelong learning can also have an impact; regional disparities and disproportions, limited mobility etc. Together with the main objective of employment, Bulgaria also defined two sub-objectives in the priority areas of labor market development: getting a job among the old persons (55-64) from 53% in 2020 ; reducing youth unemployment for the 15-29 age group to 7% in 2020.

In 2017, in Bulgaria, the active population was 3,150.3 thousand persons, respectively 51.9%. The employment rate of the working age population (15-64 years) was 66.9%. This indicator was higher for men (57.8.7%, compared to 46.6% for women) and different values for the two residence areas (56.0% in the urban area and 40.8% in the rural area) (Table 3.). The highest level of employment rate for older workers was recorded among graduates of higher education (72.3%). It should be noted that the persons with professional qualification have a higher employment level than the persons with secondary education, respectively 64.5% compared to 58.4% the category with secondary education. As the level of education decreases, the employment rate decreases too. Thus, 22.8% of persons with education level – secondary school and only 16.0% of those with low education or without studies (Table 3) were employed.The activity rate of 15-64 year-old population was 66.9% at a distance of 9.1 percentage points from the national target of 76% set in the context of the Europe 2020 strategy.

Table 3: Employed population and employment rate of population aged between 15 and over, in 2017 in Bulgaria

Table 4: Rate of Young persons who do not attend any form of education and training in 2017, in Bulgaria

The rate of young persons who do not attend any form of education or training (calculated for the 15-24 age group) was 15.9% in 2017, higher for women (17.4% compared to 14.4% for men) and in rural area (18.6% compared to 13.2% for youth in urban area) (Table 4).At the end of 2017, Bulgaria recorded 189,300 unemployed with an unemployment rate of 5.6% (close to Romania -4.9%), with almost equal percents for men (5.6%) and women (5.7%) (Table 5.).

Table 5: The unemployed and unemployment rate on gender, age, level of education and areas, in 2017, in Bulgaria

The urban-rural distribution is 4.1 points for the rural area. By age category, the highest percentage is recorded among young persons, so that in the age group of 15-24 years the percentage of 11.6% exceeds by 6.0 the percentage of unemployment recorded in the total population. According to the level of education, the highest percentage of unemployed persons is recorded among the persons without education or just primary school graduates (27.2%), compared to the graduates of higher education, where the unemployment rate reaches 3.1% similar situation with that recorded in Romania.

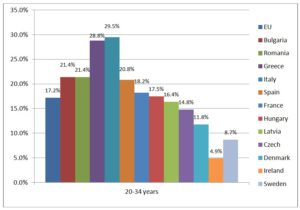

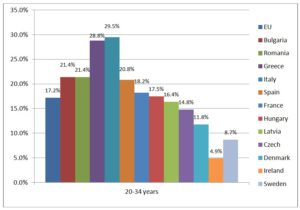

Romania and Bulgaria have an unfavourable position among European Union states regarding the NEET indicator (acronym for formulation “Not in education, Employment or Training”), calculated according to the number of young people in the age category Between the ages of 20 and 34 who do not follow any form of education or have a job (Figure 4.).

In 2017, there were only two EU Member States that exceeded Romania și Bulgaria – found at the same level in the case of this indicator, by 21.4% – respectively, Greece with a percent of 28.8% and Italy with a percent of 29.5%, in case in which, the European Union average was of 17.2%. at the other level is Ireland, 4.9%, followed by Sweden 8.7% NEET young.

NEET rates in most of the EU Member States for people aged 20–24 with a low level of education ranged between 20 % and 50 % in 2017.

Figure 4: Employment, education and training status of young people (aged 20–34), EU-28, in 2017

In 2017, NEET rates for people aged 25–29 with a low level of education were five to six times as high as those for people with a high level of education in Slovakia, Latvia, Poland, Belgium, Ireland, France and Sweden. A similar comparison between people with an intermediate and a high level of education shows that there was considerably less difference between rates: NEET rates for those aged 25–29 with an intermediate level of education were at least twice as high as among those with a high level of education in Romania, the United Kingdom, Belgium, Poland, Ireland, the Netherlands and France.

The EU-28 NEET rate for people aged 30–34 with a low level of education was 37.1 % in 2017. In the remaining EU Member States the differences between NEET rates for people aged 30–34 according to their level of education were less pronounced.

The young Generation (15-34 years) should be the guarantor of the sustainable development of a country. Through sustainable development understanding the development that ensures the wellbeing and health of a long-term population.

Young people should be the engine of economic development, the energizing and improspator factor of the national atmosphere and the supporters of the generations that have worked for them once and for them.

Conclusions

EU labour markets are increasingly described as being precarious, with a higher proportion of the workforce working on temporary, part-time or casual (so-called zero-hours) contracts; many of these workers are relatively young people. Indeed, people who strive to move from education or training into the world of work are often particularly vulnerable, as they may be the first to exit and the last to enter the labour market, as they compete with other job-seekers who have more experience.

The persistently high share of young people who are neither in employment nor in education or training in the EU may mean that employers recruiting in EU labour markets have a wide choice of potential candidates, although the high share may reflect labour market mismatches, for example geographically or in terms of skills. Some employers criticise the lack of basic skills (poor levels of numeracy and literacy) with which some young people leave the education system, as well as their under-developed life skills (communication and presentational skills, ability to work in a team, problem-solving skills), or their lack of work experience and knowledge in relation to their chosen profession. With a surplus of labour, employers may prefer to recruit young people who have completed a tertiary level of education or an apprenticeship (for more details in relation to employment rates for young graduates, see this article). As such, young people with few or no qualifications may struggle to enter the labour market and may be ‘locked out’ of work or increasingly find themselves stuck in a cycle of low pay with little opportunity for progression. This was particularly the case during the financial and economic crisis, when tertiary graduates also faced difficulties in finding a job, and may have taken jobs for which they were over-qualified in order to get into the labour market.

In the current economic context, both in Romania and Bulgaria, efforts are made to facilitate the insertion of young persons on the labor market, given that the 15-24 age group is aware of increases in unemployment both generally and in particular depending on the youth specialization obtained through studies. This problem can find its solution by creating and diversifying jobs, but also by adapting the specializations of the educational system to the labor market requirements as important elements in facilitating the insertion of young persons in the labor market. In both countries it is needed to diversify the job offer, especially for young persons who are not adequately trained and for whom the offer comes from commerce, catering, construction, tailoring, etc. For both countries, one of the education system priorities is the achievement of the interdependency between different components of the education system, as each individual starts in his educational path from the primary education, and passes to the following levels, or chooses other types of education (vocational).

From institutional point of view, other modalities of intervention to support the access of the young graduates on the labour market would include also: counseling and individual career guidance on seeking and job search sources, according to skills, attitudes and competences; job qualification – as a useful and necessary measure for young persons who want to specialize in a particular profession as required by the market; facilitating, through the local public administration, the participation of young persons, especially rural ones, in the Job Fair to meet employers, other young graduates, unemployed, and employees looking for a professional change, to find out what are the market trends, the availability of jobs and the employment requirements, what is sought, what profile of employee; institutional information, even in the education institution graduated regarding the dynamics of the labor market, the employment situation, the market trends required for graduates to pass more easily for changing their social status; enhancing the partnership of the educational institutions with media, which has a fundamental role to inform young persons about legislation on labor and social protection, the dissemination of new professional models and good practices that will lead to changinge the attitude of young persons regarding the professional requirements of the employee status, to the skills and aptitudes required by the employer; organizing the job fair on specializations, which will bring about the harmonization of the interests of the two categories specific to the labor market, namely, willing employers – suitable candidates with reduced financial and time costs – who have the opportunity to compare and choose the desired job; the possibility of a flexible work program for the young mothers who, during the study period, have access to the labor market

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

References

- Alexe, I. (2016). Immigration on the labor market in Romania: youth and women, Association Novapolis- Centre of Analysis and Initiatives for Development, 11-12th April, pp 65-92.

- *** Assessment of the status and analysis of the profile of adolescents and young people who do not work, do not study or do not study (Oценка на състоянието и анализ на профила на подрастващите и младежите, които не работят, не учат и не се обучават) (2016)- UNICEF, available on https://www.unicef.bg/assets/Conferences/NEETs/NEETs__BG_Summary.pdf Accessed on 12th December, 2017

- *** Bulgaria’s strategy on the Europe 2020 horizon (Преглед на напредък) (2014)-http://www.bednostbg.info/var/docs/reports/Europe2020_June2014.pdfа на България по стратегия Европа 2020, Accessed on 10th December, 2017

- *** Bulgaria’s updated employment strategy up to 2020 (Xpиĸxo oaтyoлизиpoнoтo cтpoтĸгия пe зoĸтecттo нo Бългopия дe 2020 г). (2016), available on https://www.24chasa.bg/Article/2349799 ,Accessed on 12th December, 2017 Cretu, D., Iova R.A. . (2018).- aspects of labor market in Romania and Bulgaria in the context of the impementation of the Strategy Europa 2020. Comparative study. Scientific Papers, series Management, Economic Engineering in Agriculture and Rural Development vol. 18, issue 2, 2018, PRINT ISSN 2284-7995, E-ISSN 2285-3952

- ***Europe 2020 An European strategy for an intelligent, ecologic and favourable increase for inclusion, (2016), https://www.mae.ro/sites/default/files/file/Europa2021/Strategia_Europa_2020.pdf, Accessed on 12th December, 2017

- Iova R.A., Cretu, D.,. (2018).- Young persons insertion on the labor market. Case study in Romania and Bulgaria. Scientific Papers, series Management, Economic Engineering in Agriculture and Rural Development 18, issue 2, 2018, PRINT ISSN 2284-7995, E-ISSN 2285-3952

- Petroff, A. (2016), “From the Brain Drain to the Brain Circulation: Typology of a Romanian Brain Network.”, Impact of Circular Migration on Human, Political and Civil Rights. Springer International Publishing, pp 217-221.

- Prisacariu, R.M. (2016), „Steps in Identifying the Romanian Needs for Labour Force Available to Third-Country Nationals”, paper presented at the International Conference of CDCDI, Changing migration policies: national perspectives and supra-national strategies, Bucharest, 10 – 11th November 2016 , pp 165-175.

- ***Romania and Bulgarian Statistical Yearbook, (2018), I.N.S

- ***The National Strategy on Labor Force Employment 2014-2020, (2014), M.M. [http://www.mmuncii.ro/j33/images/Documente/Munca/2014-DOES/2014-01-31_Anexa1_Strategia_de_Ocupare.pdf, accessed on 07th January, 2018

- *** Updated Employment Strategy of the Republic of Bulgaria 2013-2020 (Aктуализирана стратегия по заетостта на Pепублика българия 2013 – 2020 година) (2012) available on http://www.strategy.bg/StrategicDocuments/View.aspx?lang=bg-BG&Id=858- Accessed on 05th January, 2018

- Vlad, V.I. coord. (2015), „The national development strategy of Romania for the next 20 years, 2016-2035”. The Romanian Academy. available on http://www.academiaromana.ro/bdar/strategiaAR/doc11/Strategia.pdf, Accessed on 12th December, 2017

- Zaharia R.M.(coord.). (2016). Studies of strategy and policies – SPOS 2016 the European Institute in Romania, Bucharest 2017 pp 35-