Introduction

Under the recent economic crisis generated by the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak, economies are inevitably facing the risk of business failure in several important economic sectors. Thus, proper fiscal decisions are required in order to prevent labour market demand from contracting

and unemployment rate from skyrocketing. Finding the most effective fiscal policy solutions to combat the economic shocks on both the business sector and the labour market and to ensure a smoother economic recovery from the pandemic effects has become a major concern worldwide.

Therefore, now more than ever, special interest should be paid to better understand the fiscal policy’s role and to study the main fiscal tools available to keep the economies on their right track to prosperity and away from the economic recession. A fiscal policy generally deals with government spending and fiscal tools to help stabilize the economy, constantly affecting the budgetary deficit. Normally, in case of a recession, the government faces large budget deficits (also called the expansionary fiscal policy), while during prosperity, it should manage budgetary surpluses (restrictive or contractionary fiscal policy).

According to Musgrave (1984), the main functions of a fiscal policy are: allocation (measuring the desirability of intervention of the state into the economy to correct market failures), distribution (having its roots in the existence of inequalities in income distribution) and stabilization (this role depends on budgetary policy).

Fiscal policies aim to reduce fluctuations and economic instability, protect consumer incomes and stimulate development (Ialomitianu et al., 2016). It is easy to predict that any state aims or should aim for a sustainable fiscal policy. Although there is no clear and unanimously accepted definition for the notion of sustainable fiscal policy, the European Commission defines public finance sustainability as: the ability of a government to sustain its current spending, tax and other policies in the long run without threatening the government’s solvency or without defaulting on some of the government’s liabilities or promised expenditures (European Commission, 2019). Molnar (2012) concluded that, if the fiscal adjustment is based more on growth than on spending tax debt, stabilization is more likely to occur, and this stabilization is sustainable.

Compared to more developed countries, developing economies tend to have a harder and usually longer period to recover from economic crises and recessions. Therefore, this paper aims to study the changes in fiscal policies in correlation with the evolutions and transformations of the labour market for a case of a developing country. In this sense, evidence for the case of Romania will be provided. Aspects concerning the national legislative framework of fiscal policies are first briefly discussed, followed by an analysis of the evolution of the labour market in correlation with the latest labour taxation measures taken to face the current COVID-19 pandemic.

This paper is organized as follows: Section 2 briefly presents the main changes in the Romanian fiscal policy over the last two decades. Section 3 studies the dynamics of the Romanian labour market. The next section discusses future perspectives of the labour market in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, while section 5 concludes the investigation.

The history of the fiscal policy in Romania

The Romanian fiscal system has undergone major changes since 2000, when a fiscal reform simplified and standardized the Romanian fiscal regime. In 2004, the new Fiscal Code came into effect and introduced important facilities and exceptions. However, in the following years, changes to the Fiscal Code favoured higher taxation (except for the introduction of a 16% income flat tax rate in 2005 for both individuals and companies). Between 2006 and 2008, there was a relaxation of the fiscal policy, even though in 2006, Romania was in the process to become a European Union state member. The main fiscal measures consisted in reducing social security contributions by 1.5 percentage points and in introducing excise duties on tobacco and alcohol.

In the first half of 2009, the government of Romania requested a loan from the International Monetary Fund in order to overcome the 2008 economic crises and to reduce the budget deficit. For this purpose, certain measures to adjust the budget expenditures were taken (in order to better collect the budget revenues and to decrease the capital expenditures to compensate for the additional current expenses and to reach the target deficit proposed for 2009 of 7.8% of the GDP). The first part of 2010 brought a number of fiscal austerity measures, some being directly related to taxation and public spending (e.g. the introduction of the Fiscal Responsibility Law, VAT rate increased from 19% to 24%, taxation of all income by 16% with no exceptions and the reduction of public sector salaries by 25%).

In the following years, a process of fiscal consolidation took place, which was partially reversed starting with 2016, as a consequence of the new Fiscal Code coming into effect. The new Fiscal Code involved an ample fiscal relaxation, simultaneously enacting some significant increases in expenses (related mostly to salaries and pensions). Between 2016 and 2018, the fiscal policy became expansionistic, a trend that was maintained in the next period. Another major fiscal measure that came into effect on January 1st 2018 was the transfer of social contributions from employers to employees (with the change of the total amount from 39.35% to 37.25%), simultaneous with lowering the tax rate for income from salaries, pensions, self-employment and copyright from 16% to 10%.

From 2006 through 2019, Romania practiced a strongly pro-cyclical fiscal policy, stimulating the economy, but in a counterproductive manner during the periods of expansion (2006-2008, 2016-2019) and slowing down during times when the economy underperformed (2010-2015). This contributed to amplifying the economic cycle’s fluctuations and accentuated the accumulated imbalances in the economy (The Fiscal Council, 2019).

Keeping in 2017, an expansionist fiscal policy under a positive production gap only contributed to maintaining the pro-cyclical fiscal policy, which made the position of public finances more vulnerable to shocks. Furthermore, considering that the level of public debt near the end of 2019 was significantly higher than in 2008 (35.2% of the GDP as opposed to 12.4%), it is difficult to imagine the existence of a fiscal space to stimulate the economy in times of recession, putting the sustainability of public debts under risk. Moreover, the miss-fitted expansionistic Romanian policy between 2016 and 2019, together with the unsuccessful attempt to follow the European and national rules, caused the European Commission to maintain its decision to place Romania under the excessive deficit procedure. This decision comes in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic with the argument that the violation of the European tax rules predates the pandemic, and is, therefore, not attributable to it.

The most important direct taxes levied through the Romanian tax system are income tax (paid by individuals at a flat rate of 10%) and real estate taxes (taxes on buildings and land collected by municipalities), while indirect taxes include value added tax (VAT) and excise duties. In 2016, the standard VAT rate was 20%. A reduced VAT rate of 9% was applied for drugs, medical prostheses, orthopaedic products, books, newspapers, magazines, hotel accommodation or similar, as well as access to cultural and historical events and institutions. A VAT rate of 5% was additionally introduced for housing provision, as part of the government social policies. In 2017, the standard VAT rate dropped to 19% and kept constant ever since. Several other changes were also made to particular products (cultural services and supply of books, newspapers, magazines, etc. – 5% rather than 9%; the 9% rate is extended to non-alcoholic food and beverages, water supply, as well as restaurant and catering services, except for alcoholic beverages).

Aside from these direct and indirect taxes, social taxes are also levied, consisting of compulsory social and health insurance contributions (social insurance, unemployment insurance, health insurance, health insurance for medical leave and indemnities, work accidents and professional disease insurance, as well as contribution for the salary payment guarantee fund). Since 2018, the social security system has undergone major reforms through which the largest part of the contribution burden was shifted to employees.

The budget revenue structure in Romania is mostly focused on indirect taxes and income from social contributions (about 82% of tax revenue). While at the European level, there is a tendency to balance between the share of direct and indirect taxes and income from social contributions. On the expenditure side of salaries in the public sector and pensions, the ratio to budget revenues has advanced at a brisk pace in 2008-2009, reaching a peak of 75.3% in 2009 (the highest share of wages and social assistance expenditures in the total budget revenues among Central and Eastern European countries). Following the implementation of the fiscal consolidation program, this share significantly dropped between 2013 and 2015, returning to an inferior level to other CEE countries. Unfortunately, since 2016, this trend was reversed amid aggressive increases of public sector wages and pensions, Romania registering once again the highest level of wages and social assistance expenditure relative to budget revenues (72.1% in 2019 – 4.4 pp over the EU average).

Thus, in 2019, the Romanian economy was in the process of losing rhythm with regard to economic growth. The main reasons for this slowing down are, on one hand, a slowdown in external demand, and, on the other hand, a contraction of the industrial production, both caused by unfavourable external evolutions (mainly because of the commercial war between the USA and China and the positioning of the world economy in a final phase of the economic cycle, after an unusually long positive course). Forecasts of moderate levels of economic growth in Romania were radically changed following the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020. This health crisis amplifies uncertainties in assessing current and future economic policies and developments. After overcoming the acute phase of this crisis, active economic policies could accelerate the return to economic coordinates as close to the previous ones as possible. However, it is possible that post-pandemic economies may radically differ from ante-pandemic economies in many aspects.

Below are some of the main fiscal measures undertaken by the Romanian Government in May 2020 in the attempt to fight the pandemic:

(1) All tax obligations with a maturity date past March 21st 2020, which are unpaid, are not classified as arrears and are not subject to interest and late payment penalties. All tax-related seizure proceedings involving seizures are suspended (both measures cease on October 25th 2020);

(2) The deadline for local tax payment has been postponed, from March 31st 2020 to June 30th 2020;

(3) Profit tax payers/quarterly advance payment for the first, second and third quarters of 2020 benefit from a 10% discount for payments made on time. The same benefit is available to income tax-payers for micro-enterprises;

(4) The requirement to pay VAT when importing medicinal products, protection equipment, and other medical devices or sanitary equipment necessary to fight the COVID-19 pandemic has been postponed;

(5) Tax-payers subject to a specific tax will not be required to pay the tax for the times they partially or completely cease their activity during the state of emergency (there is also an exemption from the payment of the specific tax for an additional 90 days period);

(6) Enforcement proceedings by notification of state claims and subsequent recovery through offers are suspended and will not recommence (unless they are established by court decisions in criminal matters), (the suspension ends on October 25th 2020);

(7) For late payments of instalments included in a schedule of instalments remaining, outstanding until October 25th 2020, no interest and penalties will be calculated in accordance with the Fiscal Procedure Code.

In order to limit the negative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the labour market, the government adopted several emergency ordinances, concerning the following (European Semester, 2020b):

(1) Covering 75% of the salary of employees who were forced to technical unemployment by companies affected by the crisis if the activity is partially or completely interrupted or reduced as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic during the state of emergency;

(2) Support is provided to employers who, between June 1st 2020 and December 31st 2020, hire permanent full time persons over the age of 50, whose employment has ceased for reasons not attributable to them, during the state of emergency. Assistance is also provided, until December 31st 2020, for the up-to-date employment of permanent contracts of young people aged between 16 and 29, who are registered as unemployed. For each person employed in the categories mentioned above, the employer will receive 50% of the employee’s wage, over a period of 12 months, but no more than 2,500 RON (500 EUR) a month.

(3) During the period of the work schedule reduction, employees affected by this measure will receive a 75% compensation from the difference between the gross basic wage provided in the individual employment contract and the gross basic wage corresponding to the hours actually worked as a result of the reduction of the work schedule;

(4) Persons who occasionally engage in unskilled activities (day labourers) will be granted an amount, from the state budget, equal to 35% of the remuneration due for a working day for a period of 3 months;

(5) Employers who have employees with individual employment contracts for a fixed period of no more than 3 months benefit from payment by the state of 41.5% of the employers’ wages, but no more than 41.5% of the average gross salary for 2020;

(6) Employers are granted a single financial support of 2,500 RON (500 EUR) for every employee who worked remotely, during the state of emergency, for a minimum of 15 working days, in order to support the purchase of technological goods and services necessary for their business;

(7) Employees caring for children under 12 years of age can benefit from days off paid by the employer with 75% of the salary (but not more than 75% of the average monthly earnings), while schools are closed as a consequence of the measures implemented by the government.

The dynamics of the labour market

Analysing the evolution of the Romanian labour market, it is noted that in the context of economic growth in recent years, labour force participation in Romania has been among the lowest values in the European Union. The labour market is generally characterized by a slight increase in labour force participation in the years following the economic crisis, as the labour force participation rate dropped to 62.9% in 2008, then rose to 68.6% in 2019. The first two quarters of 2020 (the only ones for which data are currently available) do not yet capture the effects of the health crisis we are going through. The low values registered in Romania compared to the EU can be explained by a number of factors, such as: low internal mobility, non-correlation of demand with labour supply in terms of the need for qualifications, the lack of adequate retraining with the supply of jobs, the lack of career counselling, as well as the establishment of generous social benefits that demotivate the reintegration into the labour market.

The Romanian labour market was facing low unemployment rates in the last period (3.9% in 2019), but with visible and inevitable growth trends, taking into account the current context (in the first trimester of 2020, the unemployment rate was 4.3% and rose to 5.4% in the second trimester). In terms of gender, it is observed that the unemployment rate among women remained, throughout the analysed period, below the level of the unemployment rate for men, with differences of even 2.8 pp in 2004, but decreased to 0.9 pp in 2019.

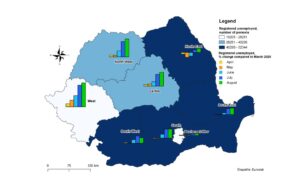

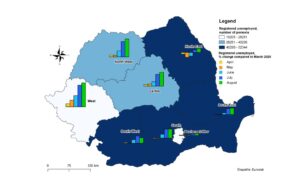

Fig. 1: Registered unemployment at regional level, 2020

Source: raw data from NIS, authors’ own calculations and representation

However, in the context of high labour migration, although the unemployment rate in Romania is below the EU average, youth unemployment is among the highest in Europe, reaching even 24% in 2014 and then declining to 16.8% in 2019. This trend, together with the fact that Romania does not yet have effective policies to stimulate the transition from school to labour market and to correlate the education system with labour market requirements, places Romania in the top 10 countries with higher unemployment rates among young people in the EU and among the last 5 countries with the lowest employment rates among young people in the EU (approximately 24.7% in 2019).

Unfortunately, this new crisis continues to affect this category of the population. If in the first quarter of 2019, the youth unemployment rate was 15.6%, in the first quarter of 2020, the unemployment rate had increased to 17.6%. It should also be noted that, depending on gender, the situation shows an interesting dynamic: if in the first years after 2000, the young female unemployment rate was 3-4 pp higher than that of the young male unemployment rate, in recent years, the situation has reversed (in 2019, the unemployment rate among young women was 1.2 pp higher than the unemployment rate among young males). It will be useful to look at how this crisis will affect young people.

Regarding the evolution of the registered unemployment on the onset of the crisis, at the regional level, increases were experienced from one month to another almost since April, the first full month with measures implemented in order to try to control the effects of the pandemic (state of emergency, with many restrictions regarding the economic activities). In comparative terms over the same month of 2019, the unemployment rate has a first strong increase in July, with increases ranging from 0 pp to 0,5 pp, with only the North-East region registering a slight decrease as compared to July 2019. The same goes if the registered unemployment rate is compared with the values of March 2020 (set as the starting point of the economic/health crisis in Romania). In August, the situation continues to deteriorate, the number of registered unemployed continues rising even more: the overall unemployment rate reaches 3.3% (compared to 2.9% in March), with almost 290 thousand registered unemployed (and even more according to the definition of unemployed from ILO – almost 480 thousands are unemployed, corresponding to an unemployment rate of 5.3%).

The most affected region so far is the West region, with 0.7 pp increase of the registered unemployment rate since March, equivalent to an increase of approximately 40% of the registered unemployed (from 13.7 thousand persons in March to 19.1 thousand persons in August). Also, the North-West region registered an increase of nearly 30% of the registered unemployed (corresponding to a 0.6 pp increase in the unemployment rate). The region around the capital seems to be the least affected, with zero or a very small increase during these months (0.1 pp in August compared to March for the unemployment rate).

From the perspective of the participation in the labour market in Romania, men were on an increasing trend in the period 2005-2019, while the participation of women in the labour market registered slight oscillations, with a maximum level of 63.6% registered in 2000 and a minimum level of 55.2% in 2008. Women’s participation in the labour market suffered a much slower recovery after the economic crisis of 2008, reaching only 58.9% in 2019, but unable to return to the level recorded in 2000, while the level registered among men in 2019 is higher than in 2000 (78% compared to 75.7%).

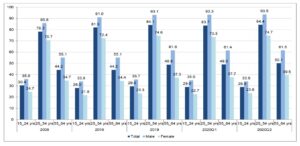

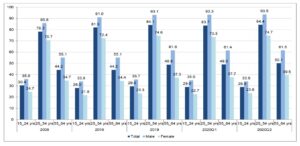

Fig 2. Labour force participation in Romania, by gender and age groups

Source: raw data from NIS and Eurostat, authors’ own calculations and representation

Regarding the evolution of the labour force participation by age groups in Romania, in the period 2000-2019, there were numerous fluctuations. The largest decrease was registered for the age group 15-24 years (11.8 pp), being more pronounced for the female population (13.7 pp compared with 10 pp for the male population). For the 55-64 age segment, there is an even more pronounced decrease among women, 10.2 pp, while the participation rate for men in the same age group increased with 3.2 pp.

The first half of 2020, for which the statistical data is available, indicates a consistent downward trend for the 15-24 age group. For the 25-54 age group, the data do not yet indicate a deterioration of the situation generated by the new health crisis, while for the 55-64 age group, the data for the first two quarters of 2020 even suggest a slight increase. However, these data should be viewed with caution, especially since the negative economic effects generated by the COVID-19 pandemic were only felt, in Romania, from the second quarter of this year.

The total employment rate (for 15-64 years) reached a minimum of 57.6% in 2005, following an upward trend in the next years, with a maximum of 65.8% in 2019. In the years following the economic crisis in 2008, the employment rate in Romania registered only a slight decrease, the period 2008-2014 being rather characterized by stagnation. However, when analysing gender differences, it is noted that while the male population maintained a steady upward trend over the period under review, the female population recorded a decline from 59% in 2000 to 56.8% in 2019.

Regarding the evolution of employment by age groups, both young people (under 25 years) and seniors (over 55 years) recorded decreases during this period: higher in the case of young people (9.3 pp) and slightly lower for those approaching retirement (4.2 pp). As for the 25-54 age group, the increase was modest, of 2.8 pp. The existing data for the first half of this year indicate a slight decrease even for this age group, from 82.2% employment in the second quarter of 2019 to 80.2% in the second quarter of 2020.

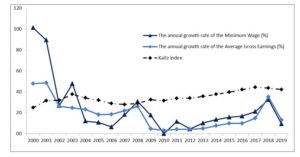

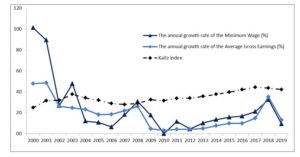

The evolution of the minimum gross wage followed an upward trend, with annual rates of oscillating growth. Similar to the evolution of the minimum wage, the average gross wage in Romania registered an upward trend, while wage inequality has declined. During 2000-2008, the annual wage growth rates were among the highest due to the economic expansion of the Romanian labour market (on average, the increase in the average gross wage was about 28% per year, while the minimum wage increased by an average of 38% per year). In real terms, until 2008, the average gross monthly earnings relative to the 2000 prices had an average annual increase of 10.6%, followed by a short period of decreasing rates on the horizon 2009-2011, and respectively a return in real terms of approximately 10.4% registered in 2015 compared to the previous year.

Fig. 3: Gross minimum wage and the Average Gross Earnings, 2000-2019

Source: raw data from NIS, authors’ own calculations and representation

In 2019, the gross minimum wage reached 2080 lei, with two distinct categories: employees in positions that require higher education receive a minimum of 2350 lei, while employees in the construction field receive a minimum wage of 3000 lei per month. The last increase of the minimum wage took place in January 2020, when it reached 2230 lei, but without affecting the other two values previously mentioned.

Following the onset of the international financial crisis in 2008, the Romanian authorities initiated a series of structural reforms, aimed at increasing labour market flexibility and improving the way the social dialogue is conducted. Consequently, in 2011, the Law on the Unemployment Insurance System and the Stimulation of Employment was amended (one important change was the termination of the allowance for the unemployed who do not participate in employment incentive programs or refuse a job suitable to their training or level of education). Also, a new Labour Code and the Law on Social Dialogue were adopted; all of them mainly aiming at regulating employment contracts and employee protection.

Future perspectives of the labour market

During the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Summit in September 2015, the world leaders adopted a set of 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The eighth goal of the 2030 Agenda advances the promotion of inclusive and sustainable economic growth, employment and decent work for all through several pillars to: increase labour productivity, decrease the informal employment, reduce the gender pay gap and reduce the unemployment rate.

Eichhorst (2017) argues that the future of employment is influenced by four main factors: globalization, technology, demographic change and labour market institutions. While globalization, technology and demographic change might be hard to control, the labour market institutions in one country have high potential to adjust to the economic context in the near future. The importance of those institutions may become even greater after this new pandemic situation; they should aim to better shape the functioning of the labour market. In order to overcome the effects of technology and globalization, together with the new developments generated by the sanitary crisis, the labour market institutions should provide different channels of adjustment (either by proposing different types of employment, different working time and wage flexibility, or/and by adapting the skill profiles to the companies’ demands).

For the case of Romania, it is more than obvious that a widespread change in the size and structure of the population already took place, together with the international large-scale movement of labour. Due to the aging population, it is expected that Romania will experience a slowdown in the growth of the workforce in the next period. Recent projections of Romania’s population by Eurostat reflect the current trends in fertility rates and net migration flows. Thus, the working age population (20-64 years) of Romania is estimated to decrease by approximately 7.5% by 2025 compared to 2019, and by another 3% between 2025 and 2030. A significant decrease should be expected in the population for most age groups less than 44 years, while for the age group (45-54 years), there might even be a slight increase in population.

According to CEDEFOP forecasting (2018), regarding the sectoral employment trends in Romania, the highest increase during the next period (2021-2030) will be in the non-marketed services sector. While among the shrinking sectors, Construction is expected to be the sector experiencing the sharpest decrease up to 2030, together with the manufacturing industry and primary sector and utilities. The economic crisis in 2008 has reduced employment in the primary sector, in construction, as well as in the manufacturing industry in the period 2008-2013. However, employment, not only in the financial services sector, but also in the distribution and transport services sector, as well as non-commercial services (especially related to the public sector), continued to increase during that period.

Regarding the occupations movement, the highest number of openings is expected not only for professionals and skilled agricultural workers, but also in legal, social and cultural professions and health professionals.

Three main areas of intervention should attract the attention of most countries (Eichhorst, 2017) including Romania: education, the regulation of labour market and active labour market policies. Regarding the education, both youth and adult formation should be considered important, and the curricula should align with the needs of the labour market. From the labour market regulation point of view, policy makers should aim to increase both labour force mobility and job security and flexibility. Attention should be also paid to forms of employment such as free-lancing or self-employment, both from the perspective of social insurance (pension, unemployment) and from the perspective of other aspects (minimum wage, work schedule). As for the active labour market policies, they can be a superior tool compared to employment protection because they target the protection of workers rather than jobs (Scarpetta, 2014).

As it becomes more and more obvious that this public health crisis is one of the worst in the last century, the world also became aware that the current economic crisis is a serious and lasting one. Moreover, it is not just an economic crisis, but also a job crisis, with many casualties in terms of unemployment and hours worked dropping sharply (OECD, 2020). Unemployment is expected to reach 10% in OECD countries by the end of 2020, up from 5.3% at year-end 2019, while jobs recovery is not expected until after 2021.

Conclusions

Labour market reforms can lead to tax costs – either directly, by changing taxes or unemployment benefits, or indirectly, using tax compensation to reduce the distributional effects of the reforms (IMF, 2014). Some labour reforms affect fiscal instruments and thus have direct budgetary implications. A clear example is the reduction of the tax burden on labour costs – the difference between the cost of labour borne by employers and the net salary of employees, due to income tax and social security contributions. Reducing the tax burden could lower labour costs and stimulate job creation, but would lead to losses in tax revenues. Active labour market policies and changes in unemployment insurance schemes can also have a direct effect on the budget. The reduction in payroll taxes has a considerable fiscal impact. IMF (2014) showed that, taking into account the effect of the business cycle and inflation on nominal budget revenues from labour tax, the reduction of the tax burden by a percentage is, on average, associated with a loss of budget revenue equal to 0.3 % of GDP.

The nature of jobs is constantly changing, with the technological progress, globalisation and ageing populations re-shaping the labour markets. Also, new organisational business models and worker preferences are contributing to the appearance of new forms of work. Moreover, the progress of the future of work is more rapid than everyone expected due to the pandemic declared by the World Health Organisation since March 2020. Specialists (OECD) argue that this economic crisis will hit the labour markets harder than the 2008 financial crisis (the hours worked fell already by 12%, compared to only 1.2 in the first months of the previous crisis).

In Romania, at the national level, the unemployment rate in 2009 was 1.1 pp higher than the unemployment rate in 2008, and increased with another 0.3 pp in the next 2 years. In the first trimester of 2020, the unemployment rate was 4.3% and rose to 5.4% in the second trimester, being already with 1.5 pp above the level registered in late 2019. The registered unemployment does not reflect this sharp increase, mainly due to the definition of the unemployed. In addition, in the months of lockdown, the unemployed were unable to actively seek jobs. It is worth mentioning the fact that the measures taken by the government in order to support labour market (workers, their families and companies) may lead to a drop in the hours worked, with the employees maintaining their jobs, instead of massive lay-offs.

Countries all over the globe reacted with unprecedented measures to contain damages and support the labour markets among other sectors. However, for the coming months and years, new and better labour market policies, along with optimal fiscal policies must be designed and implemented in accordance with the specifics of each country, taking into account the strategic objectives already proposed, such as reducing inequalities, poverty and the wage gap in societies.

Acknowledgment

Part of this work was supported by the NUCLEU Program and funded by the Romanian Ministry of Research and Innovation (Project PN 19130103).

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

References

- CEDEFOP (2018),‘Country forecasts. Romania-2018 Skills forecast’,[Online], [Retrieved October 3rd, 2020], https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/publications-and-resources/country-reports/romania-2018-skills-forecast

- Eichhorst, W. (2017), ‘Labor Markets Institutions and the Future of Work’, IZA Policy Paper,

- European Commission (2019), ‘Fiscal Sustainability Report 2018’, European Economy Institutional Paper, 094.

- European Semester (2020a), ‘Convergence Programme for 2020 Romania’[Online], [Retrieved October 3rd, 2020], https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/2019-european-semester-convergence-programme-romania_ro_0.pdf

- European Semester (2020b), ‘National Reform Programme 2020 Romania’ [Online], [Retrieved October 3rd, 2020],https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/2020-european-semester-national-reform-programme-romania_en_0.pdf

- Ialomitianu, R.G., Danu, A.L. and Bucoi, A.(2016). ‘The Effects of Fiscal Policies on the Economic Growth in Romania’,Bulletin of the Transilvania University of Brasov, 9(58).

- IMF (2014), ‘Fiscal Monitor: Back to Work: How Fiscal Policy Can Help, Chapter 2. Can fiscal policies do more for jobs?’ [Online], [Retrieved October 3rd, 2020],https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/FM/Issues/2016/12/31/Back-To-Work-How-Fiscal-Policy-Can-Help

- Molnar, M. (2012),‘Fiscal Consolidation: What factors determine the success ofconsolidation efforts?’,OECD Journal: Economic Studies, (1), 123-149.

- Musgrave, R.A., Musgrave and Peggy B. (1984),‘Public Finance in Theory and Practice’, Mc.Graw Hill Book, New York.

- Scarpetta, S. (2014),‘Employment protection’, IZA World of Labor

- ***https://home.kpmg/xx/en/home/insights/2020/04/romania-government-and-institution-measures-in-response-to-covid.html

- ***https://static.anaf.ro/static/10/Anaf/legislatie/Cod_fiscal_norme_11022020.htm

- *** http://www.consiliulfiscal.ro/RA%20CF%202019.pdf

- *** http://www.oecd.org/employment-outlook/2020/