Introduction

The architecture of Polish pension system

In 1999 Poland introduced radical systemic (paradigmatic) pension reform based on a switch from defined benefit public mono-pillar to defined contribution multi-pillar system with a mandatory funded element (Chłoń, Góra, Rutkowski 1999). However, the unfinished legislation process and fiscal pressure led to substantial changes in the reform plan. The mandatory funded pillar was substantially reduced, then it has become voluntary for new employees and finally, it will be terminated. Political risk affected mandatory pension funds. As the voluntary occupational and individual elements of the system have not developed well, the new workplace pension plans based on auto-enrollment (PPKs) have been introduced since mid-2019.

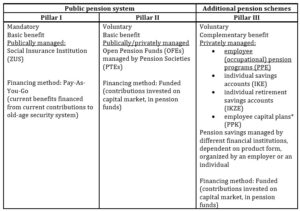

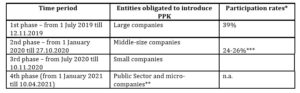

After many, sometimes contradictory changes introduced in the last two decades, the structure of the Polish pension system can be presented as follows (see table 1):

Table 1: The current structure of the Polish pension system

Note: *Employee capital plans (PPKs) are quasi-obligatory, obligatory for employers and voluntary for employees (opt-out option).

Source: Author’s own elaboration.

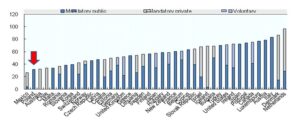

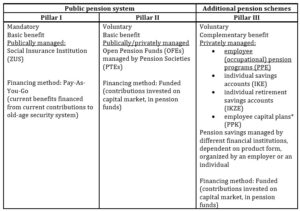

The need to develop additional pension systems — including occupational schemes — is beyond dispute. Due to the demographic aging of the population in economically developed countries (including Poland), the level of financial security offered by the public pension system has been falling systematically. In Poland, a significant reduction in the net replacement rate (the value of the pension entitlement relative to individual earnings taking account of taxes and contributions paid both on earnings when working and on pensions during retirement) is expected to go down from approx. 55% in 2017 to only approx. 34-39% in 2050 (cf. Fig. 1), while the net replacement rate for OECD countries in the mid-21st century is going to be at the level of 62-63% (OECD 2017)2.

Fig 1. Projected net replacement rate in 2050

Note: Data regarding Poland has been additionally marked with an arrow.

Source: Own study.

Under these conditions, the development of additional pension schemes is essential. However, the development of additional, voluntary pension schemes has been very weak and far from satisfying the needs. Despite the introduction of various tax incentives, only a small group of Poles has participated in the additional pension savings programs. In 2018, the participation rate in voluntary occupational schemes – the Employee Pension Plans (PPE) which have existed since 1999 was only 2% of labor force, in Individual Pension Accounts (IKE) – existing since 2004 – only 5,8%, and in Individual Pension Savings Accounts (IKZE), which have operated since 2012, only 2,6% of the working-age population (Polish Financial Supervision authority 2019). In the view of the ineffectiveness of traditional tax incentives and very poor development of additional pension savings, a new solution has been introduced – a new type of occupational pension scheme with automatic enrolment: PPKs.

Characteristics of the PPKs

PPKs remain mandatory programs for employers and voluntary for employees (an opt-out option). The design of Polish employee capital plans is based on behavioral incentives (so called “nudges” in the terminology of Richard Thaler), such as automatic features, default options, simple information and choice, as well as financial incentives. The authors of the legal and economical regulations of PPKs followed the example of programs with automatic enrollment, which have been introduced in other countries (including New Zealand and Great Britain), where the level of participation in company pension programs has been significantly increasing.

According to the initial declarations of the authors of this new scheme, the plan was to achieve one of the main goals of the Strategy of Responsible Development of February 2016 – i.e. increase the level of domestic savings and build domestic capital, which is needed for increasing investments and supporting economic growth. But as the concept started taking shape legally, much more attention was devoted to its role in supplementing the employee’s future security at old age in the face of expected decrease in replacement rates for the public pension system (Błaszczyk 2020). The authors of the PPK concept (representing mainly the Ministry of Finance and Polish Enterprise Fund – PFR) assumed that it would be a universal system that would cover the majority of employees. Initially very optimistic official predictions assumed even 70% participation rate, then they were revised to slightly over 50%.

Pursuant to the applicable law3, PPKs have been introduced gradually – since 1 July 2019 in enterprises employing at least 250 people4, in other companies since 1 January 2020 (employing a minimum of 50 people)5 and as of 1 July 2020 (employing at least 20 people), while as of January 1, 2021 – in the remaining entities, including the public financial sector.

According to the assumptions of the Act, PPKs are created and maintained for systematic saving by their participants to be paid after they reach the age of 60 (Article 3 of the Act). It is to be a universal and voluntary long-term saving system, available to all employees who are subject to compulsory retirement and disability insurance. The subjective scope of the act remains wide. It includes (Article 2, paragraph 1, point 18) not only individuals working under an employment contract but also other categories of the employed:

- persons who are at least 18 years old, performing outwork,

- members of agricultural production cooperatives and agricultural circle cooperatives,

- persons who are at least 18 years of age, carrying out work under an agency contract or a mandate contract,

- members of supervisory boards who are subject to compulsory retirement and disability pension insurance on the territory of the Republic of Poland.

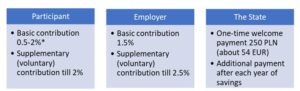

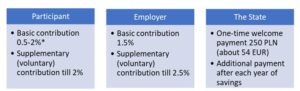

A more thorough analysis of the PPK’s Act indicates that this is not a fully voluntary system, but a quasi-mandatory one (obligatory for employers, voluntary for employees). The employer is required to enroll employees aged 18-55 in the program. An employee who has worked for at least 3 months is automatically enrolled by their employer in the program, with an option of resigning (automatic enrollment with an opt-out option). PPK uses the mechanism of automatic enrollment of employees (more precisely: of employed persons) to the program, proven in other countries, using mechanisms identified in behavioral economics (tendency to maintain the status quo, choice architecture, default options, aversion to losses). In contrast to employee pension schemes (PPE) existing in Poland, where the basic contribution is paid by the employer, the employee may or may not pay any additional contribution, as contributions to the PPK account will come from the following three sources: the employer, the employee and the state (cf. fig. 2).

Fig. 2. The financing mechanism of the employee capital plans (PPKs) – contributions

of employer, employee and the State

Note: Pursuant to the provisions of the Act of October 4, 2018 on employee capital plans, persons whose remuneration from various sources does not exceed 1.2 times the minimum remuneration, may declare in a given month, when their remuneration does not exceed this amount, a lower than 2.0% contribution to PPK from the following month.

Source: Author’s own elaboration.

In accordance to the applicable law6, the PPK’s were introduced gradually. The process started in July 2019 in enterprises employing at least 250 people7. In several successive stages, the new pension institution reached smaller companies. From January 2020, the PPK’s was introduced in companies employing at least 50 people8, from July 2020 – at least 20 people, and finally from January 2021 – the remaining entities, including the public finance sector ones.

Literature Review

The review of the literature used in this article refers to publications regarding two problem areas:

- the legitimacy and effects of using behavioral incentives (“nudges”) in pension systems (especially in occupational pension schemes with automatic enrollment);

- and preliminary assessments of the implementation of the employee capital plans (PPKs) in Poland.

In recent years, the successive waves of pension reforms have tended to move in the direction of individualized accounts and / or defined contribution contracts. These changes have opened up more opportunities for participants in pension systems to make choices. It was rightly noticed that in this way the principles of Milton Friedman, who cherished the idea that people should be free to choose, have been implemented (van Dalen and Henkens, 2017).

But more freedom of choice means that people bear the risks and consequences of their investment decisions. Unfortunately, only in economic theory individuals can make investment decisions that would enable them to optimize their future pensions. Investing requires knowledge, willpower and self-control to exercise choice. Individuals with limited cognitive abilities and limited willpower will not always act in their own best interests. As noted by Foster (2017), certain behavioral barriers make it difficult for people to save for retirement. These are in particular: myopia, cynicism and inertia. These behavioral barriers, the so-called biases, “refer to systemic, and most often unconscious, deviations from a strict economic model of rationality that many people exhibit in the face of (economic) decisions” (Lefevre and Chapman, 2017). They can be categorized according to the drivers of the decision that is affected: preferences, beliefs and decision-making process. Present bias or hyperbolic discounting belongs to the main behavioral biases affecting participation in voluntary funded pension schemes. People “respond to urges for immediate gratification in overvaluing the present over future” (Financial Conduct Authority 2013), which can lead to self-control problems (especially – procrastination, postponing decisions on additional retirement savings).

It can be inferred from this that when designing the shape of the pension system, one should take into account strategies that, on the one hand, encourage favorable behavior, and, on the other hand, halt unfavorable behavior.

In discussions about both the benefits and disadvantages of expanding the choice of pension system participants, the findings of behavioral economics have become a very important turning point. The breakthrough in this respect turned out to be the approach developed by R.Thaler and C.R. Sunstein, advocating the ideas of libertine paternalism (Thaler and Sunstein, 2003; Sunstein and Thaler, 2003). According to their findings, beneficial changes in behavior can be achieved through minimally invasive policies that prompt people to make the right decisions. To this end, the “architecture of choice”, that is, the design of the environment in which the choices are made is crucial. Thaler and Sunstein popularized the concept of nudge, which implies positive reinforcement and indirect suggestion as ways of influencing behavior and decision-making by groups or individuals (Thaler and Sunstein, 2008). They found that nudging can have the desired effect on the choices made by individuals by designing default options.

The particular importance of the default option has been noticed, inter alia, in the field of accumulating retirement savings (Madrian and Shea, 2001; Choi et al. 2004; Thaler and Benartzi, 2004; Kahneman 2012). The earliest of these studies was carried out by Madrian and Shea (2001) and found that automatic enrollment increased the participation rate in a 401 (k) savings plan from 49% to 86%. According to Kahneman (2012), one of the strategies that can help people make better decisions is to change the standard (default) opt-in (join plan) to opt-out (leave the plan). However, particularly valuable studies on the use of default options in the retirement area were proposed by Thaler and Benartzi (2004). In the article “Save More Tomorrow” they presented a four-point program to increase retirement savings. These studies proved relevant for the Pension Protection Act passed by the 2006 US Congress, which encouraged firms to implement the automatic enrollment and automatic escalation in 401(k) retirement savings plans. Benartzi and Thaler (2013) estimated, that about 4.1 million people in the US were enrolled in some kind of automatic escalation plan by 2011 and that this had increased annual savings by $7.6 billion by 2013. Nowadays, there is much more empirical evidence that changing the default choices is an effective way to improve savings decisions (Butt, Donald, Foster, Thorp, Warren, 2018; Nishiyama, Smetters, 2014).

The positive impact of behavioral stimuli on the development of complementary pension systems seems to be confirmed by the experiences of countries such as Germany, New Zealand, Great Britain, which have been successfully increasing the level of participation for several years. However, the richest empirical research, indicating the positive effects of introducing the automatic enrolment, was conducted in the US (Madrian, Shea, 2001; Choi et al., 2004, 2006; Mitchell, Utkus, 2004; Thaler, Benartzi, 2004; Benartzi, Thaler, 2007; Beshears et al., 2011). Promising results have also been confirmed by recent studies conducted in British companies (Cribb, Emmerson, 2016; Wood et al., 2017). The results of introducing automatic registration to date have encouraged other countries to start to introduce or plan similar changes in their pension systems within the next few years. This group includes: Denmark, Georgia, Ireland, Lithuania, Thailand, and Poland (Sullivan, 2019).

Also, authors of reports prepared for international organizations have stressed the importance of implementation of behavioral economics. Policies aiming to increase participation in voluntary funded pension schemes should address the issues posed by behavioral biases or low levels of financial knowledge (OECD Pension Outlook 2018).

The possibilities of the use of behavioral incentives to stimulate the development of retirement savings have also been examined in the Polish literature, especially in the context of pension economics (Sieczkowski 2015, Szczepański 2017, Pieńkowska-Kamieniecka 2017, Jedynak 2019, Bednarczyk 2018) and social security law (Balcerowski, Prusik, A. 2018).

The literature on the effects of implementing the PPKs has not been too extensive so far. Initial assessments are based mainly on qualitative research (expert interviews, document analysis, in-depth literature analysis). This trend is represented by the works of Błaszczyk (2020), who investigated the main determinants of implementing PPKs from the point of view of different stakeholders (employers, employees, regulators).

The results of own empirical surveys have been presented in research reports presenting the results of investigation of the role of PPKs in HRM (Szczepański, Kołodziejczyk 2020) and the performance of financial institutions which manage assets of PPKs (Dawidowicz 2020).

Methodology and Results Discussion

The article presents results of own survey conducted in large companies (employing at least 250 people) in the Wielkopolska Region (Western Poland) which introduced PPKs for their employees in the second half of 2019, the survey conducted by KPMG in the whole country also in 2019 (KPMG 2019), as well as the results of statistical analysis of the level of participation in the employee capital plans from July 2019 till March 2021 prepared by Instytut Emerytalny (Pension Institute) in Warsaw.

The results of own research were used to verify the following hypotheses:

H1: Only minority of employers are interested in using PPKs in their HRM strategy (as a long term incentive, the benefit increasing the level of loyalty to the employer).

H2: There is no statistically significant difference in the respondents’ replies regarding use of PPK for HRM, depending on ownership structure (Polish or foreign capital) of the company.

H3: The implementation of employee capital plans will significantly increase additional retirement savings in Poland.

H4: The use of behavioral incentives will guarantee its success, which may be measured by over 50% participation rate and universal character of the program.

The survey was conducted in August and September 2019. The research sample included 50 respondents representing 50 enterprises out of 64 large companies from the region of Greater Poland. All entities employed at least 250 people each. 20% of investigated companies belonged to foreign investors, 80% to Polish owners. The respondents belonged to HRM or Finance Department managers, responsible for PPKs implementation.

An Intentional method of selecting a research sample was used (only companies which were obliged to create PPK9). The method of data collection involved CATI, a quantitative research in the form of telephone interviews supported by computer registration of replies. To achieve confidence level of 95%, the required sample size was 44 and this requirement was met. The margin of error was 1.5 p.p. for an incidence of 5%.

In order to broaden the knowledge about PPK development prospects in the context of HRM, the following research question was formulated:

- Do employers anticipate paying out an additional pension contribution (above the statutory minimum)?

According to legal regulations, such additional contributions could be awarded to employees with longer service record or – in agreement with employee representation – be distributed according to other, non-discriminatory criteria.

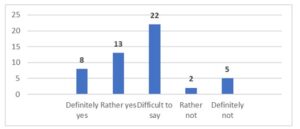

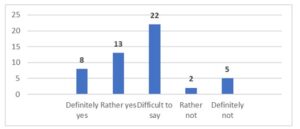

Fig. 3. Incorporation of PPK into the realization of long-term goals of HRM

Source: Author’s own study.

16% of respondents declared that they had definitely decided to incorporate PPK in their HRM strategy, but only 3 respondents (6% of the sample) made a decision to pay more than obligatory 1.5% contributions to PPK.

Although the prospects for the development of PPK are ambiguous, a clear position expressed by almost all respondents (49 responses, i.e. 98% of all enterprises) is a good sign that the introduction of PPK will not entail a reduction of existing employee benefits.

To verify the H2 hypothesis, the correlation between ownership structure and replies regarding the use of PPK for HRM policy has been tested (with Chi-Square test) and no statistical significance has been found.

These results correspond with other survey results conducted by KPMG. The survey was conducted in Poland in August 2019, with the use of CATI method on a sample of 120 medium and large companies employing over 50 people.

The results of both surveys allowed for positive verification of the H1 and H2 hypotheses.

To verify H3 and H4 hypotheses, the results of research conducted by Instytut Emerytalny (Pension Institute) in Warsaw and statistical data obtained from PFR Portal PPK10 were used.

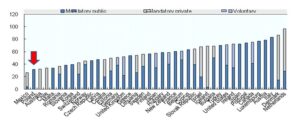

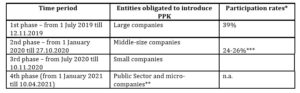

Table 2: Participation rates in the PPKs – from 2019 till 2021

Notes:

*Percentage share in the PPK of employees who remained in the program after automatic enrolment (did not use the opt-out option).

** Micro companies – companies that hire till 10 employees.

*** Data for companies which hire 50+ and 20+ employees, estimated in December 2020.

Source: Own study based on Instytut Emerytalny (2020a), Instytut Emerytalny (2020b), PFR Portal PPK (2021).

According to the PFR’s (Polish Development Fund) summary, the implementation of PPK in small, large and medium-sized companies remains at 30.4% level of employee participation. Thus, 1.7 million Poles have become convinced by the program. The legislator’s assumptions accounted for 75% of institutions providing PPK and assumed a minimum of 60% participation rate.

It is worth noting that 32000 companies, so far covered by the law, have not implemented the program effectively. These are mainly entities employing from 20 to 49 employees. This translates into the overall performance of the program. The employment by companies from the first three stages remains at 7.4 million (BeInsured 2021).

The results of statistical analyses show that so far the level of participation in the PPK – both in large enterprises and in the SME sector – is lower than the expectations that accompanied the implementation of this program. The level of participation is lower than 50%. It is too early to assess the effects of implementing PPK in the public sector.

Considering that in 2018, only about 400 000 people belonged to occupational pension programs (PPE), the result of the implementation of the PPK is the participation of new 1.7M employees in company pension systems in Poland.

It can be stated, that the H3 hypothesis has been positively verified.

When the actual level of participation in PPK so far (till March 2021) has been about 40%, it means that after or even before automatic enrollment 60% of employees decided to withdraw from the program (opt-out).

Thus, the H4 hypothesis has failed in relation to groups of employees automatically in the PPKs in 2019-2020. However, it is too early to evaluate the success of the program, until public sector and micro-enterprise employees are enrolled in the employee capital plans (which will take place by the end of May 2021). Nevertheless, the application of behavioral incentives in PPKs has turned out to be insufficient to ensure universal participation.

In addition to the previously indicated low level of interest in PPKs as a new HRM instrument on the part of employers, there are many other factors that have caused lower than expected effects of the program, including the lack of trust in the pension system on the part of employees. It can be assumed that this lack of trust results mainly from the negative experience with the nationalization of half of the assets accumulated in open pension funds (OFEs) in 2014 and the announcement of the complete liquidation of OFEs in 2021. Although the Act on PPKs guarantees their private character, there are widespread concerns that also retirement savings from PPKs could be nationalized in the future. However, a detailed understanding of the opinions and attitudes of various employee groups towards PPK requires further in-depth empirical research.

Conclusions

The lack of wider interest of employers in using PPK in the HRM strategy means that most of them treat the new program as a legally imposed obligation and an additional cost, and not as an opportunity to enrich the incentive system for employees and stimulate the development of human capital in a company. It can be stated – on the example of the current effects of the implementation of new employee capital plans in Poland – that the use of behavioral incentives (such choice architecture – automatic enrollment into the program, automatic enrollment into life-cycle funds in PPKs, simplifications etc.) does not guarantee the success of such a retirement savings program. It turns out that the actual level of participation in employee capital plans with automatic enrollment is influenced also by other factors, especially the low level of trust in the pension system on the part of employees. The explanation of this low level of confidence in pension system in Poland requires further empirical research. It can be assumed that one of the main factors contributing to this phenomenon were frequent changes in the public pension system, which often went in the opposite direction (e.g. the introduction of the second funded pillar in the public pension system in 1999, its gradual reduction in 2011 and 2014 and expected complete decommissioning in 2021).

Nevertheless, it can already be concluded that, thanks to the implementation of the PPKs, it was possible to increase the participation in additional pension schemes in Poland, also to a lesser extent than initially expected. It is too early for the final assessment of the new employee capital plans. It will be possible in the longer term, at least after the first decade of its operation.

Endnotes

[1] In 2018, 995.7 thousand individual retirement accounts (IKE) accounted for 5.8% of the total employed (KNF 2019, own calculations), and 730.4 this. in case of IKZE, i.e. approx. 4.3% of the employed (KNF 2019, own calculations).

2 This applies to the so called full-career average earners who, in the entire period of their professional careers pay contributions to the pension system (in insurance systems) or pay taxes (public pension systems financed by supply, e.g. in Denmark). Individuals who do not belong to this group and for various reasons experience pauses in their professional careers (unemployment, sickness, family care, etc.) will receive even lower pension benefits.

3 Act of October 4, 2018 on employee capital plans, Journal of Laws from 2018, item 2215 late as amended, effective as of January 1, 2019.

4 According to official data, as of January 1, 2019, the number of entities employing at least 250 people nationwide amounted to 4335 (Central Statistical Office 2019) and those entities were required to create PPK as the first.

5 Implementation deadlines for the employers from the second phase of PPK were changed in the Act of so-called Anti-Crisis Shield from 31 March 2020 (due to COVID 19 pandemic). The new binding terms for employers who employed at least 50 people on 30 June 2019 are: October 27, 2020 – for the conclusion of a PPK management contract and November 10, 2020 – for the conclusion of a contract running PPK.

6 Act of October 4, 2018 on employee capital plans, Journal of Laws from 2018, item 2215 late as amended, effective as of January 1, 2019.

7 According to official data, as of January 1, 2019, the number of entities employing at least 250 people nationwide amounted to 4335 (Central Statistical Office 2019) and those entities were required to create PPK as the first.

8 Implementation deadlines for the employers from the second phase of PPK have been changed in the Act of so-called Anti-Crisis Shield from 31 March 2020 (due to COVID 19 pandemic). The new binding terms for employers who employed at least 50 people on 30 June 2019 are: October 27, 2020 – for the conclusion of a PPK management contract and November 10, 2020 – for the conclusion of a contract running PPK.

9 Companies which run another occupational pension scheme in 2019: employee pension plan (PPE) with basic contribution 3.5% of gross salary (contribution paid by employer) were not obliged to create PPK.

10 PFR Portal PPK is a State institution responsible (together with Komisja Nadzoru Finansowego – Polish Financial Supervision Authority) for institutional and legal supervision of PPKs and financial institutions managing the assets of PPKs.

Acknowledgments

The publication of the research presented above was financially supported thanks to the Poznan University of Technology. The results of an empirical study on the implementation of the new occupational pension schemes (PPKs) in the Wielkopolska Region in Poland, presented in this article, are based on study which was conducted as a part the Project No. 11/143/SBAD/0614, financing of the research funding of Faculty of Management Engineering of Poznan University of Technology. Project Manager: Marek Szczepanski. Contractors: Tomasz Brzęczek, Andżelika Libertowska, Krzysztof Kołodziejczyk, Elżbieta Świtalska, and Maciej Szczepankiewicz.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

References

- Balcerowski, M., Prusik, A. (2018), ‘Wybrane aspekty prawne Pracowniczych Planów Kapitałowych’, Instytut Emerytalny. [Online], [Retrieved April 28, 2018], http://www.instytutemerytalny.pl/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Wybrane-aspekty-prawne-PPK-15-marca-2018.pdf.

- Bednarczyk, T. (2018), ‘Stymulowanie oszczędności emerytalnych na przykładzie KiwiSaver’, Annales Universitatis Mariae Curie-Skłodowska, 52 (1), 19-27, http://dx.doi.org/10.17951/h.2018.52.1.19.

- Benartzi, S. and Thaler, R.H. (2013), ‘Behavioral Economics and the Retirement Savings Crises’, Science, 339, 1152-1153, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1231320.

- Benartzi, S. and Thaler, R.H. (2007), ‘Heuristics and Biases in Retirement Savings Behavior’, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21 (3) 81–104, http://dx.doi.org/10.1257/jep.21.3.81.

- BeInsured (2021), PPK. Co się udało, jak będzie wyglądać ostatnia prosta wdrażania programu (cz. 2), BeInsured [Online], [Retrieved March 4, 2021], http://www.beinsured.pl/artykuly/ppk-co-sie-udalo-jak-bedzie-wygladac-ostatnia-prosta-wdrozenia-programu-cz-ii,8311.html.

- Beshears, J., Choi, J.J., Laibson, D., and Madrian, B.C. (2011), ‘Behavioral Economics Perspectives on Public Sector Pension Plans’, Journal of Pension Economics and Finance, 10 (2), 315–336, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474747211000114.

- Błaszczyk, B. (2020), ‘The Story of the Open Pension Funds and Employee Capital Plans in Poland. Will it Success this Time?’ CASE Working Papers, 13 (137), 1-56. https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3586519.

- Butt, A., Donald, M.S., Foster, F.D., Thorp, S. and Warren, G.J. (2018), ‘One Size Fits All? Tailoring Retirement Plan Defaults’, Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 145, 546–566, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2017.11.022.

- Chłoń, A., Góra M. and Rutkowski M. (1999), ‘Shaping Pension Reform in Poland: Security Through Diversity’, Social Protection Discussion Paper, 9923, World Bank, Washington.

- Choi, J., Laibson, D., Madrian, B. and Metrick, A. (2006), ‘Saving for Retirement on the Path of Least Resistance’, in: McCaffery, J. Slemrod (eds.), Behavioral Public Finance: Toward a New Agenda, 304–351, Russell Sage Foundation, New York.

- Choi, J., Laibson, D. and Madrian, B.C. (2004), ‘Plan Design and 401(K) Savings Outcomes’, National Tax Journal, 57 (2), 275-298, http://dx.doi.org/10.17310/ntj.2004.2.07.

- Cribb, J. and C. Emmerson (2016), ‘What Happens When Employers are Obliged to Nudge? Automatic enrolment and pension saving in the UK’, IFS Working Papers W16/19, http://dx.doi.org/10.1920/wp.ifs.2016.1619.

- van Dalen, H. and Henkens, K. (2018), ‘Do People Really Want Freedom of Choice? Assessing preferences of pension holders’, Social Policy and Administration, 52 (7), 1379-1395, http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/spol.12388.

- Foster, L. (2017), ‘Young People and Attitudes towards Pension Planning’, Social Policy and Society, 16 (1), 65–80, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746415000627.

- Dawidowicz, D. (2020), ‘An Initial Assessment of Employee Capital Plans’, Research Papers of Wrocław University of Economics and Business, 64 (7), 5-17, https://doi.org/10.15611/pn.2020.7.01.

- Instytut Emerytalny (2020a), ‘PPE i PPK w III kwartale 2020 roku (podmioty, aktywa, uczestnicy), Warszawa.

- Instytut Emerytalny (2020b), ‘Poziom partycypacji w Pracowniczych Planach Kapitałowych w IV kwartale 2020 roku, Warszawa.

- Jedynak, T. (2019), ‘How to Effectively Encourage Poles to Save for Retirement? The Use of Achievements of Behavioural Economics in the Construction of Employee Capital Plans’, Problemy Polityki Społecznej, 45, 33-46, http://dx.doi.org/10.31971/16401808.45.2.2019.2.

- Kahneman, D. (2011), ‘Thinking, Fast and Slow’, Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- KPMG (2019), ‘Pracownicze Plany Kapitałowe. wyzwania firm związane z wdrażaniem PPK’, KPMG.pl [Online], [Retrieved January 28, 2020], https://home.kpmg/pl/pl/home/insights/2019/10/raport-pracownicze-plany-kapitalowe-wyzwania-firm-zwiazane-z-wdrazaniem-ppk.html.

- Madrian, B. and Shea, D. (2001), ‘The Power of Suggestion: Inertia in 401(k) Participation and Savings Behavior’, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116 (4), 1149-1187, https://doi.org/10.1162/003355301753265543.

- Mitchell, O. and Utkus, S. (2004), ‘Pension Design and Structure. New Lessons from Behavioral Finance’, Oxford University Press, New York.

- Nishiyama, S. and Smetters, K. (2014), ‘Financing Old Age Dependency’, Annual Review of Economics, 6 (1), 53–76, http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev-economics-080213-041304.

- OECD (2018), ‘OECD Pensions Outlook 2018’, OECD Publishing, Brussels, https://doi.org/10.1787/pens_outlook-2018-en.

- PFR Portal PPK (2021), ‘Dla pracodawcy’, PFR Portal PPK [Online], [Retrieved March 4, 2021], https://www.mojeppk.pl/dla-pracodawcy.html.

- Pieńkowska-Kamieniecka, S. and Ostrowska-Dankiewicz, A. (2013), ‘Dopłaty do dobrowolnych oszczędności emerytalnych – ocena skuteczności rozwiązań na przykładzie Niemiec i Nowej Zelandii’, Wiadomości Ubezpieczeniowe, 3, 119-133.

- Sieczkowski, W. (2015), ‘The Application of Behavioural Finance to Enhance Voluntary Retirement Savings – Are the Solutions Universal Around the World?’, Acta Universitatis Lodziensis. Folia Oeconomica, 310 (1), 141-153, https://doi.org/10.18778/0208-6021.310.11.

- Sunstein, C. and R. Thaler, R.H. (2003), ‘Libertarian Paternalism Is Not an Oxymoron’, University of Chicago Law Review, 70, 1159-99.

- Szczepański, M. (2017). Badanie możliwości wykorzystania ekonomii behawioralnej w reformowaniu systemów emerytalnych. Finanse, Rynki Finansowe, Ubezpieczenia, 89 (5), 423-433.

- Szczepański, M., Kołodziejczyk, K. (2020). The Initial Stage of the Implementation of Employee Capital Plans in Greater Poland from the Perspective of Human Resource Management: A Research Report. Human Resource Management / Zarządzanie Zasobami Ludzkimi, 134-135 (3-4), 75-96, http://dx.doi.org/10.5604/01.3001.0014.1674.

- Thaler, R.H. and Benartzi, S. (2004), Save More Tomorrow: Using Behavioral Economics to Increase Employee Saving, Journal of Political Economy, 112, S164-S187, https://doi.org/10.1086/380085.

- Thaler, R.H. and Sunstein, C.R. (2008), Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness, Yale University Press, New York, 320.

- Thaler, R.H. and Sunstein, C.R. (2003), Libertarian Paternalism, American Economic Review, 93 (2), 175-179.

- Wood, A., Downer, K., Hulme, A. and Phillips, R. (2017), Automatic Enrolment: Qualitative Research with Small and Micro Employers, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/automatic-enrolment-qualitative-research-with-small-and-micro-employers.