Introduction

Household debt is often a necessity resulting from poor budget management. Household budget management is therefore the subject of analysis by many economists (for example: Sparkes, Wood, 2021; De Vita, Luo, 2021; Bornstein, Indarte, 2022). All these authors focused on the financial management options preferred by households, and they are united by the consensus that higher-income households have a stronger propensity to save in their financial management models. Thus, the propensity to debt can be observed in low-income households. In the literature, you can find analyses and studies related to the management of financial resources in various approaches (Guiso, Haliassos, Jappelli, 2002). In large generalizations, economists focus on specific aspects of household finance: in the context of debt (Brown, Taylor, 2008), demand for financial instruments offered in a given country (Johnston et al., 2021; Kereeditse, Mpundu, 2021; Bertola, Hochguertel, 2005) or savings (Lusardi, 2000). In the literature on household finance, it is treated as a kind of subdiscipline of financial sciences (separated and according to the subjective criterion).

In the long term, household debt can distort the stability of the financial system in the economy, regardless of the level of economic development of a country. It differs in the activities of financial institutions due to the diversified package of financial instruments available to economic entities (Wiśniewska, 2016). Researchers attribute the phenomenon of household debt primarily to two factors: the occurrence of credit restrictions and changes in interest rates (Debelle, 2004). The sensitivity of household budgets to changes in these interest rates is higher in countries where there are frequent changes in the interest rate on available loans. Thanks to the availability of financial instruments with which households complement their financial resources, many countries around the world are experiencing an increase in consumption and an increase in debt (Barba, Pivetti, 2009). The level of debt is, of course, related to household finances. According to Barba and Pivetti (2009), the highest debt in relation to income can be observed in low- and middle-income households. Household debt consists of credit card funds, but a noticeable trend is also to extract capital from owned assets in the form of real estate and use them for current consumption (Canner, Dynan, Passmore, 2002). The raising of capital from trading in fixed assets (including real estate) to increase the level of spending on consumer goods and services is a significant phenomenon in the macroeconomic consequences of growing household debt (Chomsisengphet, Pennington-Cross, 2006). The main reason for the occurrence of debt in households is the desire to maintain the level of current consumption. Researchers have noticed that households, taking care to maintain the level of current consumption in order to maintain the current standard of living even at the expense of “consuming” wealth, are in debt (Toader et al., 2021; Comelli, 2021; Bolibok, Matras – Bolibok, 2018).

The researchers considered debt from different perspectives. Credit limitation will be explored, for example, Crook (2001) and Livingstone and Lunt (2005). With regard to research on the phenomenon of household debt, it can be assumed that the level of debt may be influenced by the age of the head of the household (Wałęga, 2010) or the stage of the life cycle at which it is located. During their lifetime, consumers can get into debt long-term (mortgage debt, which is usually worn for 20 to 30 years) and short-term (consumer debt, which is the amount owed on short-term and medium-term loans). Different types of household debt are associated with changing household needs throughout the life cycle.

The life cycle of the family can be treated as a process of family development, starting from the moment of marriage, birth and upbringing of children, their independence, until its dissolution, i.e., until divorce or death of one of the spouses. In determining the phases of development of a household, characteristics such as the age of the spouses or couples forming a joint relationship, the status of the marriage and the number of children and their age, are taken into account (Andersson, 2001). Depending on the phase of the household development cycle, the needs of its members change, as a result of which the volume and structure of consumption also change, especially in the field of food, clothing and home furnishings. Thus, the structure of the age of the household and what is related to it – the number of children in the family, is an important element determining the scope and intensity of the occurrence of needs, as well as the demand for specific goods and services.

The theory created by Modigliani and Brumberg (Martini, Spataro, 2022) called the Life Cycle Hypothesis is considered to be valid and fully formed. It has become the basis for research on rational expectations in the sphere of consumption. The author of this theory points out that consumer spending, saving and debt are determined by the average household income obtained in the long term.

In the life cycle hypothesis, consumption is planned throughout life. In working age, households accumulate financial resources in order to be able to take advantage of them in the post-working age and ensure an adequate standard of living. While the distribution of income is not important for consumption, in the case of creating savings and debt, it is very important. In this model, negative savings (lack of savings and occurrence of debt) appear in the initial and final period of life. Young people take out loans for current consumption, repay them when they are in middle age and accumulate savings in old age, and during retirement they use previously accumulated financial resources (Wildemauwe, Sanroman, 2022; van Bochove, Zuijderduijn, 2022).

The life cycle hypothesis clearly indicates that households shape their consumption not only on the basis of current income, but also make a decision to save and generate debt, taking into account the amount of current and future income (Crump, et al., 2022). However, the authors of the hypothesis introduce many simplifications to this model that deviate from reality. One such assumption is that there is no element of uncertainty, which means that households are able to determine life expectancy or average income. Another simplification is the assumption of full rationality of units when optimizing the budget.

By analyzing the factors influencing borrowing and/or lending, we can therefore indicate the potential determinants of household debt. The willingness of households to borrow depends on the level of disposable income of households and the purposes of borrowing. The primary reason for household debt is to smooth out consumption and investment (Cumming, Hubert, 2022; Dunn, Olsen, 2014). With the development of behavioral economics, subjective factors play an increasingly important role in the analysis of the identification of factors determining the financial behavior of households (Grzywińska-Rąpca, 2021; Nanda, Banerjee, 2021; Lee, 2021; Iramani, 2021). They are expressed as assessments of the material and financial situation.

A review of the literature indicates various factors influencing household debt levels. Demographic, economic and market factors are mentioned as the main factors. In this study, the analysis concerned subjective assessments that can be included in the group of behavioral factors. The aim of the article was to show that subjective assessments have an impact on the objective dimension of household debt. Analyses were also carried out to show that the age of the household head (which indicates different phases of the household life cycle) differentiates household behaviors in the area of debt.

Empirical Analysis

Methodology

The survey used anonymized secondary data collected by the Central Statistical Office as part of the Household Budgets survey, in which 36,166 households participated. The survey of household budgets is conducted using the representative method, which gives the opportunity to generalize, with a certain precision, the results obtained to all households in the country. In order to draw the sample, a two-stage, layered draw scheme with different probabilities of selection on the first stage was used. The units of the first-degree draw were statistical regions or teams of regions, and on the second stage household dwellings were drawn[1].

The choice of this group of households was dictated by the fact that in the group of high-income households there is little indebtedness to meet current needs (which is also shown later in this article). The survey selected those households that obtained an average equivalent income of PLN 9,000.00 and more (less than one and half the value of the national average). As a result of this selection, further analyses were carried out on 9,388 households.

In connection with the research objective: whether subjective assessments have an impact on the objective dimension of household debt, in the first stage of the survey thirteen variables (subjective assessments) were reduced to three. For the purposes of the analysis, they were defined as: the level of satisfaction of current needs (S1), debt characteristics (S2) and subjective assessments of the expected change in the financial situation (S3). At this stage of the study, factor analysis was used. According to Walesiak and Bąk (1997), the aim of factor analysis is to identify “common factors hidden in a set of variables, reducing the dimensions of variable spaces […] and the transformation of the system of variables into a qualitatively new system of main factors”.

In further analysis, regression analysis was used. This procedure made it possible to determine the relationship between subjective assessments (S1, S2 and S3) and objective household debt in the form of credit cards and loans and advances in four fractions of households (according to the age of the head of the household). Using linear regression analysis, the parameters of the equations were estimated (Table 1 and Table 2). Thanks to these parameters, the relationship between the considered variables was mapped.

Economic research taking into account subjective assessments in the financial or material situation is becoming increasingly popular in economic analyses (Grzywińska-Rapca, 2020). This is perhaps the result of interdisciplinary analyses conducted by behaviorists. Some empirical studies indicate that subjective high assessments, e.g., of the financial situation, of households, are connected with the level of income obtained. Research by Dudek (2013), Liberda et al., (2012), Kasprzyk (2016), Wołoszyn, et al. (2019) and Grzywińska-Rąpca and Grzybowska – Brzezińska (2021) indicates that satisfaction is also influenced by such factors from the group of socio-demographic factors as the age or education of the head of the household. The analyses included the following assessments:

- Assessment of the financial situation of the holding;

- Observed change in financial situation in the last 12 months;

- Which of these terms best describes the way you manage money in your household?

- Assessment of the level of satisfaction of your household’s food needs;

- Assessment of the level of satisfaction of the needs of your household regarding the purchase of clothing and footwear;

- Assessment of the level of satisfaction of your household’s health care needs (visits to doctors, medicines, etc.);

- Assessment of the level of satisfaction of your household’s needs for timely payment of housing fees;

- Assessment of the level of satisfaction of the needs of your household regarding the furnishing of the apartment with furniture and durable goods;

- Assessment of the level of satisfaction of your household’s cultural needs (purchase of cinema tickets, etc.);

- Assessment of the level of satisfaction of the needs of your household for tourism and leisure outside the place of residence holidays, etc.);

- Expected change in the financial situation in the next 12 months;

- Characteristics of household debt;

- Characteristics of the possibility of saving a household.

As a result of the reduction, three components were distinguished: (S1) assessment of the level of satisfaction of current needs, (S2) assessment of the possibility of managing savings and debt and (S3) assessment of changes in the financial situation of the farm. The median of respondents’ ratings for the variable Characteristics of household debt is that we do not have any debt. This indicates that for high-income households, debt is not a heavy burden. The median of respondents’ ratings for the variable The expected change in the financial situation over the next 12 months will remain unchanged.

Results

As quantitative variables describing the level and forms of debt of high-yield households, the following were considered: loans and credits taken out from banks by credit card, other loans and credits taken out from banks. In order to describe the phases of the household life cycle, the age fractions of the household head were distinguished: under 35 years, 35-50 years, 50-65 years and over 65 years.

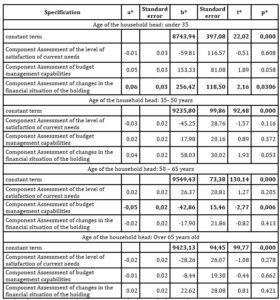

The estimated parameters of the regression equations for the variables representing the components in relation to debt in the form of loans and credits contracted with banks by credit card are presented in Table 1.

Table 1: Regression parameters for the relationship between subjective assessments of the financial situation of households and debt (loans and credit card credits)

*a – slope; b- intercept; t – t-Student statistics; p – p-value (p critical value <0,05)

Source: Own study using Statistica 13.3.

The regression carried out, taking into account the division into age fractions, allows us to conclude that in the group of households characterized by the age of less than 35 years, no statistically significant relationship was observed between the subjective assessments adopted for the analysis and the level of loans and credits taken out by credit card. A similar situation occurs in the age groups of the head of the household 50-65 years and over 65 years. In the group represented by respondents aged 35–50, a statistically significant relationship (p = 0.03) was observed between loans and credits taken out in banks by credit card and the expected change in the financial situation over the next 12 months (S3). If the expected change in the material situation of the household over the next 12 months increases by 1, then the explanatory variable will decrease by 45.44 units of the variable explained with an average error of 20.96 units of the explanatory variable, ceteris paribus. In no fraction of high-income households at the same time, a relationship was observed between the Assessment of the level of satisfaction of their household’s food needs S1 and the Characteristics of household debt (S2) and the level of loans and credits taken out by credit card.

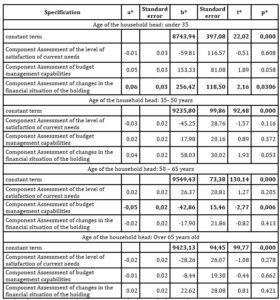

The situation is slightly different in the case of the relationship between the variables representing the components in relation to debt in the form of loans and credits taken out in banks (Table 2).

Table 2: Regression parameters for the relationship between subjective assessments of the financial situation of households and debt (loans and credits other than credit cards)

*a – slope; b- intercept; t – t-Student statistics; p – p-value (p critical value <0,05)

Source: Own study using Statistica 13.3.

In the group of households under 35 years of age, there was no statistically significant relationship between the Assessment of the level of satisfaction of current needs (S1) and the Characteristics of household debt (S2) and the level of loans and advances taken out in banks. A similar situation occurs in the age groups of the head of the household 50-65 years and over 65 years. In the group represented by respondents under the age of 35, a statistically significant relationship (p= 0.03) was observed between loans and credits taken out in banks and the expected change in the financial situation over the next 12 months (S3). If S3 increases by 1, the explanatory variable will increase by 256.42 units of the explanatory variable with an average error of 118.50 units of the explanatory variable, ceteris paribus. In the group of households whose head was characterized by an age of 35 – 50 years, no relationship was observed between S1, S2 and S3 and the level of loans and credits taken out in banks. A similar situation can be observed in the age group of the head of the household over 65 years.

At the age of 50-65 years, an association was observed at the level of significance p = 0.005 between S2 and the level of loans and credits taken out in banks. If S2 increases by 1, the explanatory variable will decrease by 42.86 units of the explanatory variable with an average error of 15.46 units of the explanatory variable, ceteris paribus. At the same time, a link was observed between S1 and S3 and the level of loans and advances taken out from banks.

Referring to the above results, it can be concluded that despite the small relationships between the variables representing the components: S1, S2 and S3, and the level of loans and advances taken out in banks, age is a factor that differentiates the described phenomenon.

Summary

Empirical studies on household debt indicate that in household debt generation behavior (current and long-term) so-called personal characteristics such as education or gender, income and the age of the household head play an important role (Campbell, 2006; Alfaro and Gallardo, 2012). Using the original data collected by the Central Statistical Office, the impact of fiscal assessments of the financial situation of households on the objective dimension of household debt was examined. The study was conducted in four fractions of the age of the household head in order to achieve the second objective of the study: does the age of the household head differentiate the behavior of households in the area of indebtedness?

The main findings were as follows: (1) a statistically significant relationship was found between subjective assessments of the material situation of households and the level of debt, and (2) differences were shown in the level of relationship between subjective assessments of the financial situation of households and the level of debt depending on the phase of the life cycle (four fractions of the age of the head of household). The obtained results indicate the fact that the research goals have been achieved.

The main author’s contribution of this article was a statistical analysis carried out on a set of data on the impact of subjective assessments of debt and material situation on the debt of high-income households, taking into account four fractions (determined on the basis of the age of the head of the household). An attempt was made to determine which of the separated fractions of households shows the greatest “sensitivity” of subjective assessments in the context of debt generation. This is important because in the era of the development of behavioral economics, subjective assessments of the material situation of households take on importance in many economic analyses. Secondly, the presented study may be a source of suggestions for financial institutions to prepare new credit instruments focused on a specific fraction of households.

Bibliography

- Alessie, R., S. Hochguertel, A. Van Soest (2000) Household portfolios in the Netherlands. Working Paper, 2000-55;

- Alfaro, R., Gallardo, N. (2012). The determinants of household debt default. Revista de Analisis Economico, vol. 27, No 1, p. 55-70.

- Andersson, B. (2001) Portfolio allocation over the life cycle: Evidence from Swedish household data. Working Paper, 2001: 4;

- Barba, A., M. Pivetti (2009) Rising household debt: Its causes and macroeconomic implications — a long-period analysis. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 33(1), 113-137.

- Bertola, G., S. Hochguertel (2005). Household debt and credit. White Paper. Luxembourg: Wealth Study Perugia Meeting.

- BOLIBOK P., A. MATRAS-BOLIBOK. (2018). “Has household debt become a substitute for incomes? An evidence from the OECD countries,”Proceedings of the 32nd International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA), ISBN: 978-0-9998551-1-9, 15-16 November 2018, Seville, Spain, p 5183-5198.

- Bornstein, G., S. Indarte (2022). The Impact of Social Insurance on Household Debt. Available at SSRN 4205719

- Brown S., K. Taylor (2008) Household debt and financial assets: evidence from Germany, Great Britain and the USA. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society), 171(3), 615-643.

- Campbell, J. (2006). Household Finance, The Journal of Finance 61(4), pp. 1553-1604.

- Canner, G., K. Dynan, W. Passmore (2002) Mortgage refinancing in 2001 and early 2002. Federal Reserve Bulletin, 88, 469;

- Chomsisengphet, S., A. Pennington-Cross (2006) Subprime refinancing: equity extraction and mortgage termination. St. Louis: Research Division Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Working Paper Series, 2006-023A. http://research.stlouisfed.org/wp/2006/2006-023.pdf.

- Comelli, M. (2021). The impact of welfare on household debt. Sociological Spectrum, 41(2), 154-176

- Crook, J. (2001) The demand for household debt in the USA: evidence from the 1995 Survey of Consumer Finance. Applied Financial Economics, 11, 83–91.

- Crump, R. K., S. Eusepi, A. Tambalotti, G. Topa. (2022). Subjective intertemporal substitution. Journal of Monetary Economics, 126, 118-133

- Cumming, F., Hubert, P. (2022). House prices, the distribution of household debt and the refinancing channel of monetary policy. Economics Letters, 110280.

- De Vita, G., Y. Luo (2021). Financialization, household debt and income inequality: Empirical evidence. International Journal of Finance & Economics, 26(2), 1917-1937;

- Debelle, G. (2004). Household debt and the macroeconomy. BIS Quarterly Review, March 2004.

- Dudek, H. (2013) Subiektywne postrzeganie sytuacji dochodowej–mikroekonometryczna analiza danych panelowych. Roczniki Kolegium Analiz Ekonomicznych, 30, 219-233.

- Dunn, L., Olsen, R. (2014). US household real net worth through the Great Recession and beyond: Have we recovered?. Economics Letters, 122(2), 272-275.

- Grzywińska-Rąpca M., (2021). Economic Welfare and Subjective Assessments of Financial Situation of European Households. European Research Studies Journal. 24 (2), s. 948-968, DOI: 10.35808/ersj/2166.

- Grzywińska-Rąpca M., Grzybowska-Brzezińska M. (2021), Savings and Investments of European Households in the Context of Their Subjective Assessments of the Financial Situation, 38th International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA), 2767-9640.

- Grzywińska-Rąpca, M. (2020), Assessment of the smilarities of Selected European Countries in terms of Socio-economic Diversity, 37th International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA), 7228-7239.

- Guiso L., M. Haliassos, T. Jappelli (red.) (2002). Household portfolios. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Iramani, R., L. Lutfi. (2021). An integrated model of financial well-being: The role of financial behavior. Accounting, 7(3), 691-700.).

- Johnston, A., G. W., Fuller, A. Regan (2021). It takes two to tango: mortgage markets, labor markets and rising household debt in Europe. Review of international political economy, 28(4), 843-873.;

- Kasprzyk, B. (2016) Subiektywne oceny dobrobytu ekonomicznego w gospodarstwach domowych w świetle modelowania dyskryminacyjnego. Ekonomista, 2, 233-250.

- Kereeditse, M. K., M. Mpundu (2021). Analysis of Household Debt in South Africa Pre-and Post-Low-Quality Asset Financial Crisis. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 11(5), 114

- Lee, S. (2021). Financial Knowledge, Overconfidence, and Financial Behaviors of Individuals (Doctoral dissertation, The Ohio State University).

- Liberda, B., M. Pęczkowski, E. Gucwa-Leśny (2012) How do we value our income from which we save? Annals of the Alexandru Ioan Cuza University-Economics, 59(2), 93-104.

- Livingstone S.M., P.K. Lunt (1992) Predicting personal debt and debt repayment: psychological, social and economic determinants. Journal of Economic Psychology, 13, 111–134.

- Lusardi, A. (2000) Explaining why so many households do not save. Chicago: Irving B. Harris Graduate School of Public Policy Studies, University of Chicago.

- Martini, A., L. Spataro,. (2022). The contribution of Carlo Casarosa on the forerunners of the life cycle hypothesis by Franco Modigliani and Richard Brumberg. International Review of Economics, 69(1), 71-101

- Nanda, A. P., R. Banerjee. (2021). Consumer’s subjective financial well‐being: A systematic review and research agenda. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 45(4), 750-776.

- Sparkes, M., J. D. Wood (2021). The political economy of household debt & the Keynesian policy paradigm. New Political Economy, 26(4), 598-615.

- Toader, D. A., G. Vintilă, Ș. C. Gherghina (2021). The impact of microeconomic and macroeconomic factors on financial structure: Evidence from United States. Journal of Economic Studies and Research, 1-10

- van Bochove, C., J. Zuijderduijn. (2022). Years of plenty, years of want? An introduction to finance and the family life cycle. The History of the Family, 1-20

- Walesiak, M., Bąk, A. (1997). Wykorzystanie analizy czynnikowej w badaniach marketingowych.

- Wałęga, G. (2010). Determinanty zadłużenia gospodarstw domowych w Polsce w świetle wybranych teorii konsumpcji. Otoczenie ekonomiczne a zachowania podmiotów rynkowych, Polskie Towarzystwo Ekonomiczne, Kraków.

- Wildemauwe, J. I. R., G. Sanroman. (2022). Household debt and debt to income: The role of business ownership. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 83, 52-68. .

- Wiśniewska, A. (2016) Determinanty nadmiernego zadłużania się polskich gospodarstw domowych. Współczesne Finanse. Teoria i Praktyka, 1, 91-100.

- Wołoszyn A., R. Głowicka-Wołoszyn, S. Świtek, M. Grzanka (2019) Wielowymiarowa subiektywna ocena materialnych warunków życia i dobrostanu w gospodarstwach domowych rolników w Polsce. Fragmenta Agronomica, 36(4), 15-26.