Introduction

In the year 1900, the global population was around 1.6 billion and experienced a significant increase to 6 billion by 2000. Recent data from 2023 show that the population has now exceeded 8 billion, highlighting rapid and continuous growth. This dramatic rise is particularly noticeable when observing the milestones within the last century: the world population reached 2 billion in the year 1927, 3 billion in 1960, 4 billion in 1975, 5 billion in 1987, 6 billion in 1999, 7 billion in 2011, and the latest milestone of 8 billion in 2023 (Worldometers, 2023). The rapidly growing global population and the increasing scarcity of resources necessitate a shift towards more sustainable management practices. This change aims to address and mitigate environmental, economic, and social factors effectively.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, the importance of the delivery sector became increasingly evident as it emerged as a highly demanded service. Platforms specialising in last-mile delivery, such as Glovo, Uber Eats, Tazz, Bee Fast, and the more recent Fan Delivery, emerged and were instrumental in this growth. These platforms, characteristic of the GIG (Gandini apud Malik, Visvizi & Skrzek-Lubasińska, 2021) economy — represent a short performance, a term coming from frequently used academic discussions to characterise the short, flexi- or project-based jobs — have not only bolstered the growth of e-commerce but also fostered an entrepreneurial mindset, primarily by collaborating with independent contractors. This trend has led to a marked increase in the establishment of new delivery companies worldwide, with notable growth in Romania. Given these developments, it is imperative to scrutinise the financial sustainability of these companies in a broader economic framework. These new business models have disrupted traditional management strategies in conventional courier companies, increasing reliance on outsourcing. This evolution places significant pressure on meeting economic Key Performance Indicators (KPIs), underscoring the need for an in-depth analysis of their financial stability in this changing environment. This examination is relevant to the delivery sector and may have implications for other industries, as the democratisation of GIG work is prevalent.

In order to assess the economic sustainability of the Romanian courier companies compared to the rest of the economy, I analysed the most relevant economic indicators reported by ANAF (the National Agency for Fiscal Administration) and collected by ListăFirme.ro website. I conducted research analysing active companies from across Romania, namely from the 41 counties, namely: Alba, Arad, Argeș, Bacău, Bihor, Bistrița-Năsăud, Botoșani, Braila, Brașov, București, Buzău, Călărași, Caraș-Severin, Cluj, Constanța, Covasna, Dâmbovița, Dolj, Galați, Giurgiu, Gorj, Harghita, Hunedoara, Ialomița, Iași, Ilfov, Maramureș, Mehedinți, Mureș, Neamț, Olt, Prahova, Sălaj, Satu Mare, Sibiu, Suceava, Teleorman, Timiș, Tulcea, Vâlcea, Vaslui and Vrancea counties, with Codes 5310 and 5320 CAEN Economic Activity Classification, covering the entire delivery market. The current research deep dives into the financial performance of the delivery companies as the Profit pillar of sustainability, putting the delivery market into the larger economy of Romania.

Romanian companies vs. delivery companies

Over the past 14 years, 2008-2021, the number of companies in Romania has continued to grow from 662.803 as registered in 2008, reaching in the year 2021 the number of 845.728, which means a difference of 182.925 companies, equal 28% increase. The only downfall was registered during the economic crisis from 2008 and 2009. This may indicate a flourishing setting for economic activities and a greater appetite for entrepreneurial activities, influenced by the increased financial education and stability, governmental facilities, start-up programmes and sometimes economic necessities to supplement the income with additional revenue apart from the salaries.

Fig 1. Evolution of the number of companies at the national level between 2008-2021

Fig 1. Evolution of the number of companies at the national level between 2008-2021

The delivery companies registered a tremendous increase in the same period, from 641 in 2008 to 4.488 in 2021, which means a substantial increase of 600%. The historic evolution registered in 2020, the year when the COVID-19 pandemic started, registering a peak of 35% increase from the previous year, 2019, only overtaken by the percentual increase registered in 2011. In 2020, 891 new delivery companies were founded, which is the second most significant difference (after the year 2011, as a percentage increase), and overtaken by 2021 registered 1.056 new companies, which represents a 31% difference from the previous year, meaning the most remarkable difference as a number from the analysed years and the third percentual increase after the year 2011 (47%), and 2020 (35%). In 2021, out of 845.728 companies, 4.488 were delivery companies, making up 0,53% of the total. This was a 31% increase from the previous year. In 2020, there were 819.356 companies in total, with 3.432 being delivery companies. This made up 0,42% of the total, a 35% increase from 2019. In 2019, out of 794.491 companies, 2.540 were delivery companies, making up 0,32% of the total. This was a 17% increase from 2018. In 2018, there were 758.477 companies in total, with 2.170 being delivery companies. This made up 0,29% of the total, an increase of 11% from 2017. In 2017, out of 732.860 companies, 1.948 were delivery companies, making up 0,27% of the total. This was a 14% increase from 2016. In 2016, there were 699.220 companies in total, with 1.704 being delivery companies. This made up 0,24% of the total, a 9% increase from 2015. In 2015, out of 680.136 companies, 1.558 were delivery companies, making up 0,23% of the total. This was an 11% increase from 2014. In 2014, there were 674.834 companies in total, with 1.407 being delivery companies. This made up 0,21% of the total, a 12% increase from 2013. In 2013, out of 662.618 companies, 1.260 were delivery companies, making up 0.19% of the total. This was a 16% increase from 2012. In 2012, there were 657.074 companies in total, with 1.082 being delivery companies. This made up 0.16% of the total, a 7% increase from 2011. In 2011, out of 652,099 companies, 1,007 were delivery companies, making up 0.15% of the total. This was a significant 47% increase from 2010. In 2010, there were 614.598 companies in total, with 684 being delivery companies. This made up 0,11% of the total, a 4% increase from 2009. In 2009, out of 631.988 companies, 659 were delivery companies, making up 0,10% of the total. This was a 3% increase from 2008. In 2008, there were 662.803 companies, with 641 being delivery companies, constituting 0,10% of the total. Following the economic crisis of 2008-2009, delivery companies experienced a period of modest growth, which continued at a gradual pace. However, 2019 marked a significant upturn in the market, triggered by the entry of the GIG delivery platform into the Romanian market, alongside a broader entrepreneurial trend fuelled by educational podcasts and TV shows in the financial domain. The years 2020 and 2021 witnessed a further increase in both the number and percentage of growth, a trend sustained even after the easing of pandemic restrictions.

Fig 2. Evolution of the number of delivery companies at the national level between 2008-2021

One can notice that while Romanian companies followed a similar growth trajectory, the surge was not as pronounced as the delivery companies, indicating a heightened interest in the delivery sector. Despite inadequate road infrastructure, the surge in delivery can be attributed to several factors. These include the prevailing economic standards, the favourable tax policies on importing second-hand vehicles coupled with lenient pollution regulations, the affordability of vehicle maintenance, the low prices of fuels, the adoption of electrical vehicles, and the widespread acceptance of the GIG economy. This growth is further propelled by the presence of international GIG players like Glovo and Uber Eats and local entities such as Tazz by eMAG, Romania’s largest e-commerce platform. Generally, delivery companies depend highly on road infrastructure, and Romania is no exception. Given the geographical structure of the territory, including mountains, heels and plain areas, the delivery companies are established in large, well-connected economic poles, around the capital city, the city with the highest economic power and the county around it, as well as the main university cities in Romania.

Therefore, most companies in delivery are established in Bucharest, namely 765, which represents 0,47% out of the total 162.330 companies established in Bucharest as the reports of the balance sheet of 2021 reveal, the capital city of Romania, followed by 273 established in Ilfov, 237 delivery companies are based in Cluj, 217 are based in Timiș and 146 in Bacău counties, 136 in Brașov, the same number as in Iași, Mureș follows with 126 delivery companies and 109 in Constanța, followed by the 108 delivery companies based in Dolj county. The delivery companies are concentrated around the economic poles of Romanian cities, the most numerous companies being situated in the South-East, North-West, West, East, Centre, East, Center, South-East and South-West, mainly depending on the infrastructure. On average, at the national level, delivery companies, as reported in 2021, represent 0,42% out of the total number of Romanian companies, varying from 0,26% in Tulcea – which has only 19 delivery companies – to 0,47% in Bucharest, where 765 delivery companies are established. For the past 13 years, the number of companies in Romania has slightly increased from one year to another, starting in 2011, from 662.827 in 2008, reaching 845.728 by the end of 2021, an increase of approximately 27,59%. The evolution varied from one year to another between –2,74% (in 2010) and +6,08% (in 2011). The major urban centres, mainly Romania’s capital and several key economic regions, serve as primary hubs for the delivery sector, with most deliveries occurring within cities rather than between them. This trend can be partly explained by Romania’s limited road infrastructure, which includes only two highways and predominantly single-lane roads connecting cities. This lack of extensive and efficient road networks makes intercity deliveries more challenging, thus concentrating delivery activities within urban areas, especially last-mile deliveries.

CAENs for delivery sector

In Romania’s economic environment, the difference between GIG businesses and traditional courier firms lies not in their basic character or specific delivery methods, but in the varieties of transportation they use. Conversely, CAEN (Classification of Activities in the National Economy) 5310 is designated for “Postal activities under universal services”, which involves delivering standard postal items like letters and postcards. Meanwhile, CAEN 5320, known as “Other postal and courier activities”, covers a broader range of services beyond traditional postal duties, including parcel delivery, courier services, and the transportation of important documents. Based on the information provided by ListăFirme.ro website with public data from ANAF (the National Agency for Fiscal Administration), in the year 2021, 4.488 active companies are operating in Romania under the two respective CAEN codes, 5310 and 5320, as their most predominant CAEN activity. Of this total, the most significant proportion of companies, comprising 52,92%, are SRLs (Limited Liability Companies). The second-largest group, representing 44,13% of the total, comprises 4.736 PFAs (Authorized Physical Persons). The remaining types of companies include 199 II (Sole Proprietorships) representing 1,85%, 89 SRL-D (Limited Liability Companies for Startups) representing 0,82%, 13 SA (Joint-Stock Companies) representing 0,12%, 13 IF (Family Enterprises) representing 0,12%, and two other types of companies representing 0,01% of the total number of delivery companies.

Fig 3. Distribution of Delivery Companies according to their type

The high percentage of LLCs in the national economy in Romania can be attributed to their favourable taxation rates. Specifically, LLCs with no employees were taxed at about 3% of their income, while those with at least one employee can sometimes enjoy a rate as low as 1% and 5% on dividends. Additionally, Authorized Physical Persons benefit from perks like immediate money withdrawal and a low taxation rate of approximately 10% of their income. The ease of registration and a straightforward accounting system further incentivise entrepreneurs to opt for this type of company. On the other hand, the limited presence of Joint-Stock Companies in Romania is due to the substantial amount required for incorporation, around 20.000 euros. Moreover, Romania’s long history of individualism, nurtured over five decades of communism, has resulted in a low-trust culture. This lack of trust has diminished cooperation and promoted individual work, further discouraging the establishment of Joint-Stock Companies.

At the national level, in 2008, the number of companies stood at 662.827. The following year, in 2009, there was a decrease of 4.65%, bringing the total to 632.033 companies. In 2010, the total number of companies dropped to 614.696, marking a decrease of 2,74%. However, in 2011, there was a significant increase of 6.08%, leading to a total of 652.104 companies. The growth continued into 2012 and 2013, although at a slower pace, with an increase of 0,76% and 0,85%, respectively, bringing the total number of companies to 657.083 and 662.635. In 2014, there was an increase of 1,84%, reaching a total of 674,834 companies. The following year, in 2015, the growth slowed down slightly, with an increase of 0,79% to 680.136 companies. In 2016, the growth picked up again with an increase of 2,81%, resulting in 699.222 companies. This growth further accelerated in 2017 with an increase of 4,81%, reaching 732.860 companies. In 2018, another increase, though slightly slower at 3,50%, brought the total to 758.477 companies. In 2019, the total number of companies grew by 4,75% to 794.491. In 2020, despite the global challenges, the growth continued at a slightly slower pace of 3,13%, leading to a total of 819.356 companies. In 2021, there was a steady increase of 3,22%, resulting in a total of 845.728 companies. This trend demonstrates the resilience and dynamism of the business sector over these years. The most tremendous increase of companies at the national level was registered in 2011 when +37.408 newly formed companies were established, followed by the second largest increase registered in 2019 when +36.014 new companies were reported, the third largest increase was in 2017 when +33.638 Romanian companies were opened. Delivery companies registered a tremendous increase in 2011 – of 47% from the previous year, reaching 1.007 and continued to grow at a flat pace until 2019, when a 35,12% increase was registered, and in 2020, the number of delivery companies continued to increase with 30,77% than the previous year, growing from 2.170 delivery companies in 2018 to 2.540 companies in 2019 and reaching 3.432 in 2020 and reaching a historical maximum of 4.488 companies in 2021, a difference of 1.056 companies.

Between 2008 and 2021, the number of delivery companies at the national level increased by 600%, a difference of 3.847, from 641 to 4.488 companies. In 2008, there were 641 delivery companies, marking an increase of 2,81% from the previous year. This growth continued into 2009, with a rise of 3,79% resulting in 659 delivery companies. The growth rate significantly surged in 2010 by 47,22%, leading to 684 delivery companies. In 2011, the number of delivery companies increased by 7,45% to 1.007, followed by another increase of 16,45% in 2012, raising the total to 1.082. The upward trend continued into 2013 and 2014, with a rise of 11,67% and 10,73%, respectively, leading to a total of 1.260 and 1.407 delivery companies. In 2015, the total number of delivery companies rose by 9,37% to 1.558. This growth rate accelerated in 2016 with an increase of 14,32%, totalling 1.704 delivery companies. The positive trend persisted in 2017 and 2018 with growth rates of 11,40% and 17,05%, respectively, bringing the total number of delivery companies to 1948 and 2.170. In 2019, there was a significant leap with a 35,12% increase in delivery companies, totalling 2.540. The growth continued into 2020, even though at a slightly slower pace of 30,77%, leading to a total of 3.432 delivery companies. In 2021, the number of delivery companies increased further to 4.488, marking a significant expansion of this sector over these years. This period reflects the resilience and dynamic nature of the Romanian business sector, especially in the delivery industry, which withstood global challenges and thrived, reaching new heights in 2021.

Within the European Union, enterprises are classified based on size criteria. Micro-enterprises are defined by their annual turnover, which does not exceed €2 million. Small enterprises with fewer than 50 employees must have an annual turnover that does not surpass €10 million. Medium-sized enterprises are those with fewer than 250 employees and an annual turnover not exceeding €50 million. Finally, large enterprises are identified by having 250 or more employees and an annual turnover that exceeds €50 million. (All Companies Fulfilling the Definition of a Micro Enterprise Are Also Small and Medium, and All Small Are Also Medium. Are These Categories Mutually Exclusive, or Should a Micro Enterprise Be Counted One Time per Each Category? | SFC Support Portal, n.d.)

According to ListăFirme.ro, on a national level, there were 374.263 enterprises with no employees and 410.382 enterprises with 1-9 employees. In the delivery sector, there were 1.632 enterprises with no employees and 1.911 enterprises with 1-9 employees, making up a significant portion of the national and delivery sectors. The delivery sector is segmented into a diverse mix of types of companies on the national level. Out of a total of 3.876 companies operating in the field of postal services and parcel delivery in Romania, the distribution by size is as follows: very large companies represent 0,04% of the total, Large Companies make 0,13%, whereas medium-sized companies only make 0,74%, the small companies comprise 6.79%, while micro-enterprises are the most of them – comprising 78.65%, most of them being subcontracted by the large players to cover certain areas in the country or outside of it.

There are only 2 very large companies, Delivery Solutions SA, also known as Same Day Courier, and Fan Courier Express SRL, located in Bucharest. There are 6 large companies in the field of postal services and parcel delivery in Romania. Compania Națională Poșta Română SA is the national postal operator, DHL International Romania SRL, FedEx Express Romania Transportation SRL, Cargus SRL, Dynamic Parcel Distribution SA and Pink Post Office SRL, located in Bucharest and Ilfov county. There are 33 medium-sized enterprises in Romania: UPS Romania SRL, situated in Otopeni, Ilfov county; GLS General Logistics Systems Romania SRL, located in Sibiu county; and Pascal SRL, based in Brasov. Inbox Marketing SRL operates in Sectorul 1, Bucharest, while Data Curier SRL is based in Focșani, Vrancea county. BW Expres SRL has its operations in Craiova, Dolj county. Rodiser Expres SRL operates out of Târgu Mureș, Mureș county. B&G Trans Company SRL is situated in Piatra Neamț, Neamț county. Courier Service Expres SRL is based in Arad, while Delizsanz SRL is headquartered in Odorheiu Secuiesc, Harghita county. Romcurier SRL operates in Aleșd, Bihor county, and Fan Life Expres SRL is located in Târgoviște, Dâmbovița county. Mindcare Express SRL has its operations in Iasi. Other companies on the list, such as Heracle Business Fun SRL, Soft Consulting SRL, Biatis Trans SRL, Dacis SRL, Smart Post Solutions SRL, Express Curier SRL, Pandoras Courier SRL, New Look Advertising SRL, Fan Distribution SRL, AC Business Invent SRL, Capriccio SRL, Alyalim Ava SRL, ACM ATM SRL, Interawb SRL, Trans Curier Express SRL, AK Post Courier Services SRL, Ovolg Logistics SRL, Smart Total Delivery SRL, CNF Curier Logistic SRL, and BMB Multifunctional SRL, are also essential players in the courier and logistics industry, each servicing different regions across Romania. Nevertheless, an overwhelming number of delivery companies are micro-enterprises, 3.530, and 305 are small.

Turnover

In 2021, the equity of Romanian companies was 1.329.206.055.028 lei, and that of courier companies was 2.127.479.827 lei, which makes approximately 0,1601% of the total. The largest segment of the Romanian companies according to their turnover categories reported in 2021 is 33,9%, which represents companies with 100.001 and 1.000.000 lei, followed by the second largest category, which represents 23,6% that reported 0 turnovers, the 3rd most prominent category is the that registered between top 10.001 and 100.000 lei, following 12% of the total companies reported in 2021 a turnover between 1.000.001 and 10.000.000 lei, only 2,1% have a turnover between 10.000.0001 and 100.000.000 lei and only 0,02% exceed 1.000.000.001 lei.

The turnover patterns among Romanian companies indicate a link between a company’s revenue and its size. These data point to a predominance of small and micro-enterprises in Romania’s business landscape, with medium-sized and large enterprises usually associated with higher turnovers being less common. This trend mirrors the broader economic structure of Romania, where smaller businesses are more prevalent. It also underscores opportunities for economic progress and expansion, especially in fostering the growth and support of medium and large enterprises.

The lowest turnover of delivery companies reported for the past 13 years was in the year 2008 – with 2.285.990.137 lei, which continued to grow from one year to another, except for the year 2010 when there was a slight decrease to 2.516.867.813 lei, reaching a maximum of 7.239.126.940 lei in the year 2021. The average turnover for the overall delivery companies during the analysed period was 3.749.881.015.

Between 2008 and 2013, the highest turnover was 886.835.536.378 lei, reported in the year 2009. An absolute historic value of 301.681.882.443.829 lei was registered in the year 2020, approximately 340 times larger than the lowest turnover in 2009. Unlike the overall market, the delivery companies did not face the same proportional growth from the previous years. For example, the difference between 2019 and 2020 turnover was 1.025.072.479 lei, approximately 19,15% from the previous year. Nevertheless, despite the national drop in value, 2021 was the best year for the delivery sector by far, the turnover increased from 6.377.998.397 lei to 7.239.126.940 lei, a difference of 861.128.543 lei representing approximately 13,49% increase.

The best performing companies from this point of view are located in the following counties: București, Ilfov – the same as in the delivery companies, whereas at the national level, the top counties are: 3) Timiș, 4) Cluj, 5) Prahova, 6) Constanța, 7) Brașov, 8) Bihor, 9) Sibiu, 10) Mureș, whereas in the delivery sector, ascends to the top 3) Sibiu, goes one position down – ranking the 4) Timiș, 5) Cluj maintains its position, 6) Prahova goes one place down in the top, 7) Bihor ranks one position above the national top, 8) Giurgiu enters the top of the delivery, 9) Brașov goes down 2 positions from the national top, whereas 10) Iași is a new entry in the delivery top performing companies, that reveal the importance of the strategic location.

In conclusion, over the span of the financial crisis from 2008-2009, delivery companies managed to expand their turnover, achieving a threefold growth over ten years (2011-2021). This surge can be attributed to the rise in the number of newly established delivery companies. The higher demand and market increase correlated with technological development and the adoption of applications. In the pandemic year, there was a significant uptick in the turnover of Romanian companies, contrasting with the delivery companies whose growth was more gradual, experiencing minor declines in a few years.

Assets

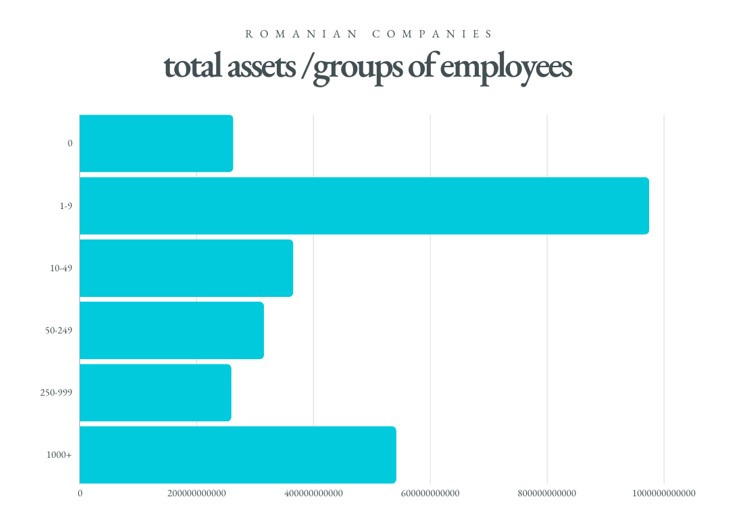

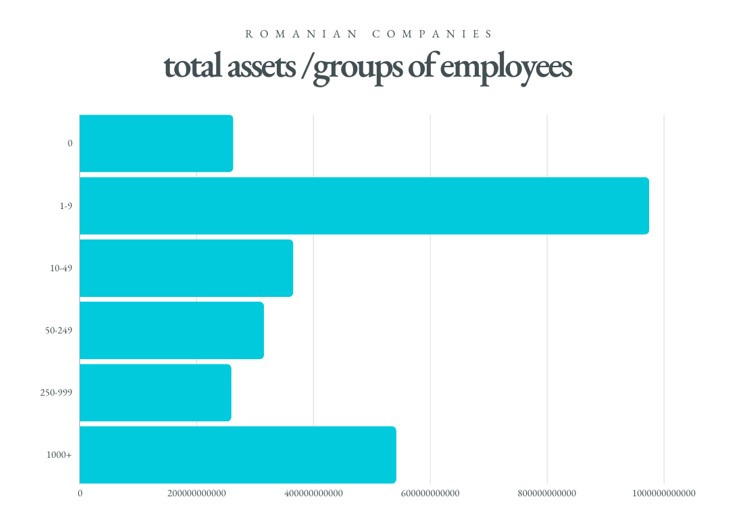

The assets of the delivery companies exhibited a proportional escalation year after year, mirroring the upward trajectory of their turnover. It is interesting to note that on the national level, smaller companies (1 to 9 employees) hold the most assets, almost double the second largest category with +1.000 or more employees, which could indicate a high asset concentration level within small enterprises. Whereas, delivery companies with 0 employees hold the most assets, slightly more than those of large companies with +1.000 employees.

Fig 4. Romanian companies’ total assets/groups of employees

Fig 5. Delivery companies’ total assets/groups of employees

Employees

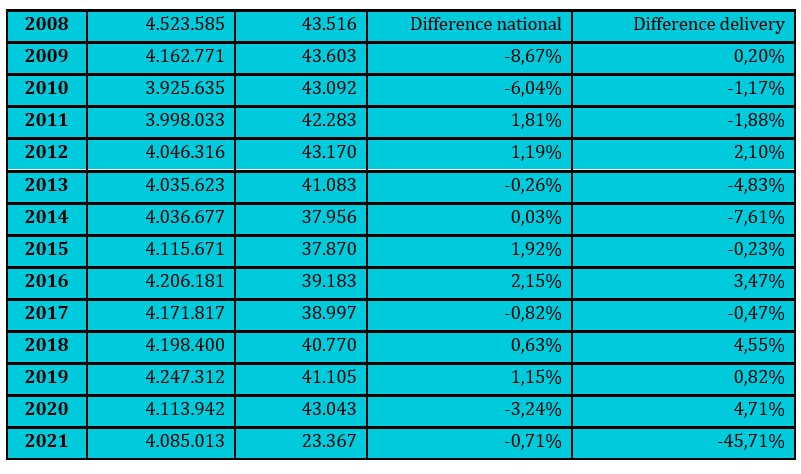

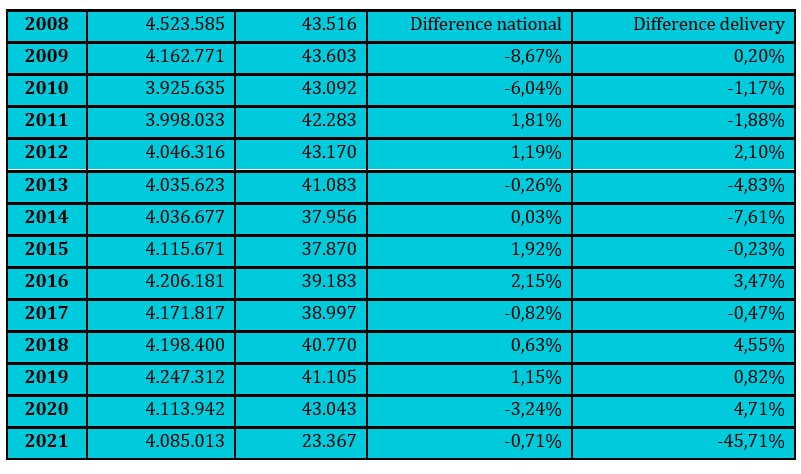

The national economy has generally maintained a stable employment count, with some fluctuations, but without a significant trend up or down. The most significant decrease happened during the global financial recession in 2009 with an 8,67% decrease from the previous year. The employment number hit its lowest point in 2010 at 3,92 million but has since generally recovered, ending at 4,09 million in 2021, slightly below the 2008 level, a difference of about half a million employees, that can be explained because of the migration of Romanians in Western European countries.

At the national level, 4.072.626 employees were reported in 2021, whereas the delivery companies employed 21.943 people in the same year. Between the years 2008 and 2021, on average, Romania has had 4.133.335 employees, whereas the delivery sector only has had an average of 39.931 employees. In 2008, the Romanian companies were working 4.523.585 employees, and their number has decreased over time. A historic drop of –8,67% was recorded in 2009 from the previous year, which continued in 2010 with –6.04%, the economic crisis year. Although the number of employees at the national level began to recover in 2011, with +1,81%, the difference was almost half a million lost jobs, and the number of employees had never reached the values of the year when the recession started in Romania. 2019 was a flourishing year, reaching a maximum number of employees after the economic crisis from 2008 – 2009; therefore, Romanian companies reported 4.247.312 employees. However, it did not last long because in 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic started, so the employees’ number dropped by -3,24%, reaching 4.113.942, a negative difference of 133.370 jobs, and the losses continued in the year to come.

The delivery sector has followed the global market trends with slight differences and particularities, and it has seen more fluctuation and a decreasing trend in later years. Like the other economic sectors, delivery registered a maximum of employees in 2008, employing 43.516 people. Since then, their number has constantly decreased over the years, reaching a historical rate in 2021, cutting in half their number, and reaching 23.367 people. In 2020, when the pandemic kicked off, unlike the general number of employees, the percentage of couriers increased by 4,71% from the previous year, already being on an ascending path, almost reaching the level of 2008 and 2009. The organic growth from one year to another has been interrupted by the jobs lost in 2021 when the restrictions rose, and the war in Ukraine started. The number of employees in the delivery sector remained stable until 2013, when it began a decline that became particularly noticeable from 2013 to 2014, with a 7,61% drop. A slight recovery was observed from 2015 to 2020, with a particularly sharp increase of 4,71% in 2020, likely linked to the rise in e-commerce and home delivery services during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, a dramatic decrease of 45.71% was recorded in 2021, indicating a significant disruption in the sector.

Table 1: Number of employees at national level vs. delivery companies

The fluctuations in employment numbers in Romania were significantly influenced by several key factors: the Global Financial Recession of 2008-2009, the migration of Romanians to Western Europe after the EU integration (2007), the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, and advancements in automation and process efficiency. Following the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a notable influx of foreign workers into Romania, particularly in the delivery sector for GIG platforms like Glovo and Tazz by eMAG. To meet the growing demand for last-mile delivery services, my research, which included interviews with solopreneurs working as couriers, revealed that individuals from countries like Bangladesh, India, and various African nations often use intermediary companies to secure employment with partner companies in the delivery sector.

In order to find out more about the sustainability of the delivery sector, I designed and distributed a survey through social media channels such as Facebook, LinkedIn, Instagram, and specifically in Facebook Groups targeting GIG delivery workers. It was also sent via email to 1.010 active delivery companies listed on ListăFirme.ro. From the 49 responses received, 36 participants (73.5%) indicated they currently work at a delivery company, while 13 respondents (26.5%) reported having previously worked at a delivery company. Glovo emerged as the most common employer among couriers, with 26 having worked there, more than double the number for the next most frequent companies, Bolt Food and Tazz, each having 10 couriers. Following closely was Food Panda, with 7 couriers, despite being acquired by Glovo in 2021. Other companies like FAN Delivery and Uber Eats, each with 3 mentions in our survey, showed fewer couriers, possibly due to Uber Eats exiting the Romanian market in 2020 and FAN Delivery being a newer entrant in 2021. Bee Fast, Bringo, and FedEx Express each had 2 couriers in our survey. The practice of multi-apping, working for multiple delivery companies, is also evident in Romania. According to the survey, 20 respondents worked for one company, 6 for two companies, 7 for three companies, and 2 had experience working with four companies.

Of the 49 respondents, 86% are men and 14% are women (only 7). The age distribution among the couriers who responded to my questionnaire is as follows: 9 couriers are between 19-25 years old, 22 couriers are between 26-35 years old, 9 couriers are between 36-45 years old, 6 couriers are between 46-55 years old, and 3 couriers are between 56-65 years old. Most respondents (70%) have a higher education, indicating a well-educated group of couriers. A smaller percentage (14%) have a medium education level, while only a very small portion (2%) have a master’s degree. Among the respondents, there are various other jobs they have in addition to delivery. These include video production, consulting in the HORECA field, counselling, insurance, previous full-time and part-time jobs, commercial work, economist, sales, teleselling, theatre, administration, architectural work, accounting, installation services, real estate, programming and 51% of the respondents mention delivery is the only source of income they have. 64% of the respondents live in a city with over 200.001 inhabitants, followed by 12% who live in cities with 100.001 – 200.000 inhabitants and only 6% live in rural areas. 20% are Entrepreneurs with employees, followed by Part-time employees at a partner company of the delivery app and Solopreneurs (entrepreneurs without employees), equally distributed – 18,4%, 16,3% represent students, Full-time employees at a partner company of the delivery app and Employees at the parent company (such as Bolt Food, Glovo, Tazz, etc.) represent 12,2% and 2% is represented by one retired person, 12% represent other types of status.

Payment is one aspect that needs improvement, couriers mention, and demand proportionally increased pay for deliveries that require long-distance and heavy weights. Some ask specifically for increasing the multiplier and setting performance bonuses that are less difficult to achieve, increasing more substantially for double orders, which are now paid 2 lei extra. The minimum order should be 10 lei, and for double orders, the minimum should be 15 lei, as they mention. Some invoke closing contracts with fleets employing illegal immigrants on $500 salaries. Couriers have voiced diverse demands for improved compensation, with some seeking higher per-delivery rates, increased kilometre rates, enhanced benefits, bonuses, or multipliers. Given that many GIG couriers work for intermediary fleets, there are calls for higher salaries, including requests for a fixed salary plus a commission on completed deliveries. Additional suggestions include hiring skilled professionals, improving the work environment, providing necessary equipment, and offering financial incentives for overtime.

Couriers are advocating for better pay, including double compensation for overtime. They also propose increased rates for multiple orders, not just minor increments like an extra 2 lei, and higher bonuses to counteract the effects of inflation. Other suggestions are guaranteed hourly earnings during slow periods, performance-based bonuses, and transparent earnings for all couriers. They recommend increasing income and bonuses based on couriers’ commitment and performance, making hard-to-reach bonuses more achievable, and providing financial rewards for working weekends. The focus is also on prioritizing employees and clients by reducing profit margins. There is a call to prevent indirect pressure on employees to work excessively long hours (up to 84 hours per week) to earn a reasonable income. Adjustments to multipliers in line with inflation and living costs are also requested. As restaurant prices and delivery fees rise, couriers argue for commensurate pay increases, highlighting the value of treating them as unique, professional, and loyal individuals, which can save costs, reduce fraud, and enhance the brand’s image in the long run. One suggestion is to increase the delivery fee to at least 10 lei per order and a minimum of 15 lei for double orders.

On the other hand, following discussions with senior executives from delivery companies, it became evident that retaining staff is a significant challenge in the delivery industry. Companies face high turnover rates, particularly among their younger employees, due to operational and logistical hurdles. The unpredictability and increasing demands of the younger workforce pose difficulties for companies striving to maintain a stable and committed team. This retention issue is exacerbated by the need to balance maintaining profitability and providing competitive salaries and benefits, which are crucial for keeping employees.

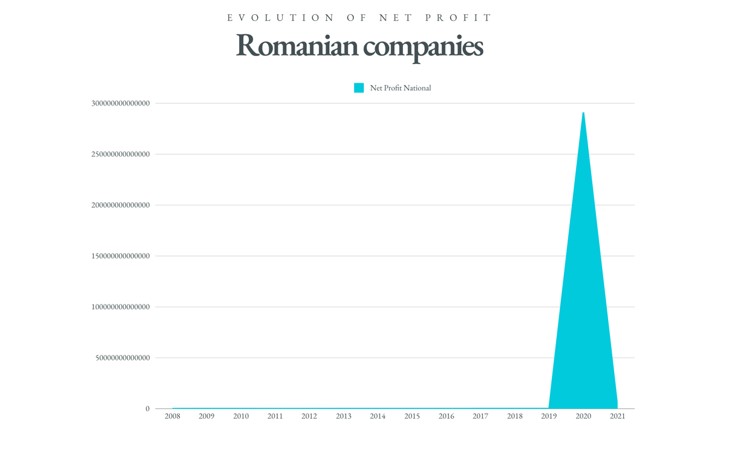

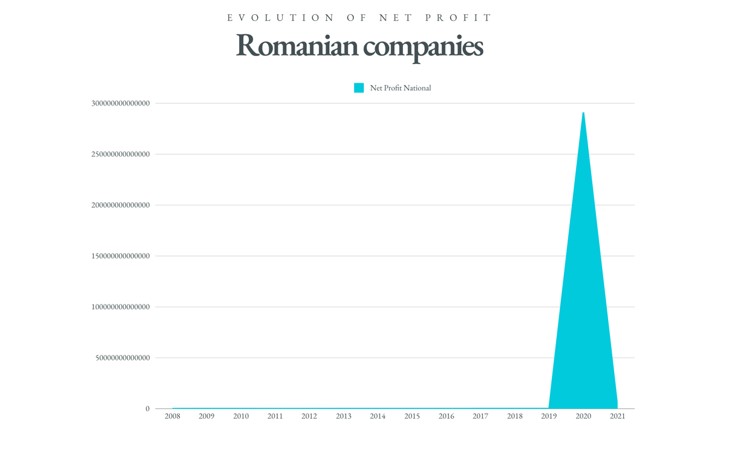

Profit

Romanian companies have reported in the year 2021 a total net profit of 199.830.667.088 lei, whereas the delivery companies made 0,31% of it, with 617.502.265 lei reported. At national level, the year with a historic profit was the pandemic year when the Romanian companies reported 291.152.213.448.858 lei, a difference of 291.015.413.358.811 from the previous year, primarily because of the high expenditure with COVID-19 related purchases such as medical services and home appliances that would help population cope with the long-stay quarantine and isolation periods. In 2021, net profit returned to the average values when 200.310.015.446 lei were reported, representing a difference of 145.214,39% decrease from 2020. Nevertheless, the values remain above the average and previous values recorded before the pandemic. Starting in 2008, the net profit was 54.660.814.733 lei. There was a slight increase in 2009 to 63.065.052.842 lei, representing an increase of approximately 15,38%. The profit dropped slightly in 2010 to 63.850.004.127 but decreased more significantly in 2011 and 2012 to 55.935.387.003 and 55.761.147.570, respectively, showing a decrease of approximately 12,43% from 2010 to 2011. However, in the year 2013, there was a slight increase in net profit to 62.192.243.948. The following year, 2014, marked a more substantial growth in profit to 69.433.207.365, representing an increase of approximately 11,63% from the previous year. The net profit consistently grew in the following years, reaching 85.131.300.779 lei in 2015, 97.003.032.606 in 2016, and 108.439.772.931 in 2017. These yearly increments represented an increase of about 18,54% from 2015 to 2016 and approximately 11,77% from 2016 to 2017. The growing trend in net profit also continued in 2018, reaching 122.119.022.992 lei. This trend significantly accelerated in 2019, with net profits jumping to 136.800.090.047, marking a growth of about 12,02% from the previous year. A historic surge in net profit was witnessed in 2020, with a total of 291.152.213.448.858 lei, when the COVID-19 pandemic started. However, the profit decreased to more normal values than before the pandemic, reaching 200.310.015.446 lei in 2021, yet a significant increase compared to 2019.

Fig 6. Evolution of net profit Romanian companies 2008-2021

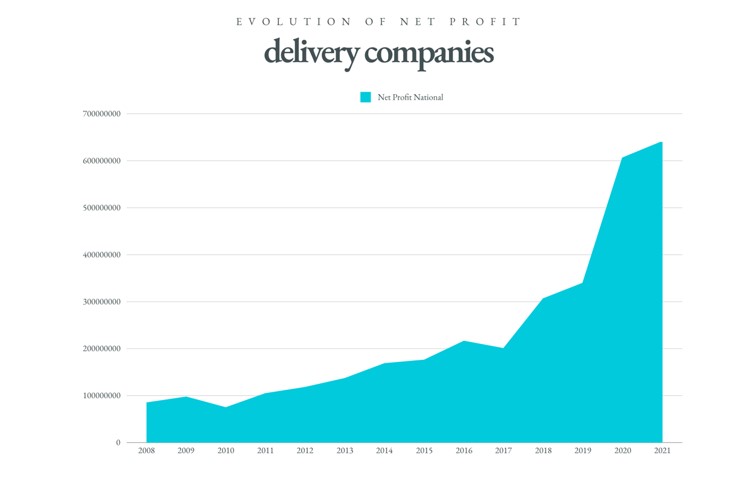

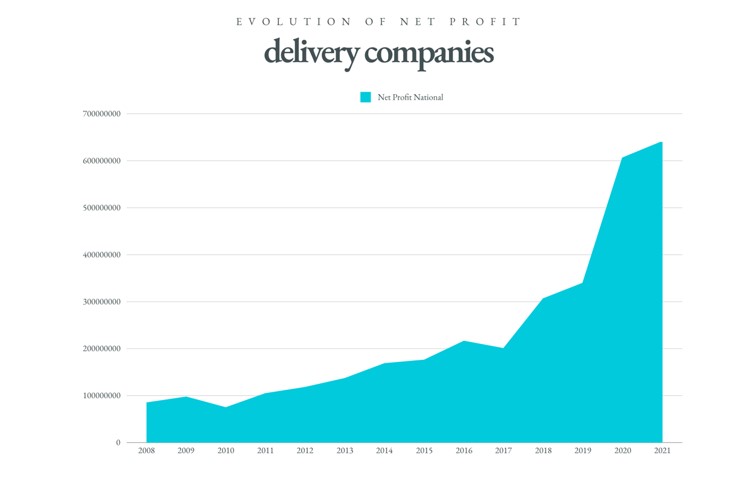

With respect to the delivery companies, over the past decades, they continued to increase their net profit, except for the years 2010 and 2017, when the numbers dropped. However, the overall values significantly increased from one year to another, reaching their peak in 2021 when a historic net profit of 640.177.353 lei was reported. The pandemic years have almost doubled the net profit of the delivery companies in Romania, from 338.690.311lei to 605.322.041 lei, an iconic value that the industry has never seen before. Between 2021, which registered a net profit of 640.177.353 lei, and 2020, which registered 605.322.041 lei, the absolute difference was 34.855.312. In 2008, the net profit of the delivery companies was 83.638.234 lei. It slightly increased in 2009 to 96.140.782, marking a jump of approximately 14,96%. However, the profit decreased to 73.332.286 in 2010, representing a substantial decrease of 23.76% from the previous year due to the economic recession from 2008 and 2009.

A positive turnaround was witnessed in 2011 when the net profit increased to 103.492.574, marking an increase of approximately 41,16% from the previous year. This upward trend continued in 2012, with the net profit reaching 116.707.731. In 2013, the net profit grew to 135.691.510, and this growth trend persisted into 2014 when the profit rose to 167.352.918 lei. This increment represents a growth of about 23,35% from 2013 to 2014. The year 2015 saw a further increase in net profit, reaching 174.755.575 lei. However, 2016 marked a substantial jump to 215.010.749, signifying a growth of approximately 23,07% from the previous year. In 2017, the net profit dropped slightly to 199.206.778 lei, but it bounced back in 2018 to 305.408.614 lei, marking a significant growth of approximately 53,34%. The growth trend was consistent in 2019, with profits rising to 338.690.311 lei. The net profit continued its upward trajectory in 2020, reaching 605.322.041 lei, which represents an unprecedented growth of approximately 78,70% from the previous year. The profit continued to grow in 2021, although at a slower pace, reaching 640.177.353 lei, representing a growth of about 5,76% from the previous year.

Fig 7. Evolution of net profit delivery companies 2008-2021

People, Planet, Profit

To delve into the sustainability of delivery companies, I conducted a comprehensive qualitative research study focusing on semi-structured interviews with managers in the delivery sector. The research aimed to evaluate how management practices within these companies align with the three pillars of sustainability: People, Planet, and Profit. This involved a detailed exploration of management functions across various dimensions. The research scrutinized various managerial functions, starting with Planning, where strategies around Recruiting, Retention, and Exit were analysed for their sustainability alignment. The Organizing function was assessed for its approach to managing CO2 emissions and optimizing business interactions. This included a review of the organizational structure and business processes. It delved into the business model, scrutinizing hourly- and task-based frameworks, and assessed the sustainability impact of different contract types, including full-time, part-time, and contractor agreements.

The research revealed that traditional delivery operations typically have centralized headquarters overseeing fleet management, route optimization, and operational efficiency. A multi-tiered staffing structure involving Headquarters, Operational, and Contractor roles was evaluated for its environmental footprint. This extended to an assessment of various resources, from natural elements like air and water to technological and human resources.

Under the Directing and Coordinating function, procedures, decision-making criteria, and coordination flows were explored, focusing on their impact on sustainability and potential improvements. The study highlighted the innovative use of AI-driven algorithms, reporting systems, and key performance indicators in assessing their effectiveness and sustainability alignment. The Budgeting aspect involved analysing staff roles across different levels and how resources, ranging from natural to technological assets like vehicles and office equipment, are allocated.

The research found that traditional employment in the delivery sector often entails a structured 9-5 work schedule, with roles and responsibilities clearly defined, contrasting with less structured environments in other countries. Drivers, for instance, face various stressors such as traffic safety, physical exertion, adapting to early starts, time pressures, and ensuring goods are delivered in optimal condition. As described by a 52-year-old veteran in the field, the planning in delivery companies involves careful consideration of numerous factors, including distance, driving hours, vehicle type, freight size, and weather conditions. Automation has become more prevalent in sorting processes, with new employees needing to learn company procedures, GPS usage, and barcode scanning. Peer support plays a vital role in this learning process, underscoring the importance of professional relationships. Finally, the research suggested that delivery sector jobs could benefit from syndicate protection, with organizations like ARTRI in Romania and various Drivers’ Unions in Europe providing support. It also highlighted the need for managerial empathy and better workload distribution to avoid service quality issues and potential accidents, which can ultimately be more costly than perceived savings from lean staffing.

One delivery company manager noted that the reliability of new hires is often inadequate and not just due to salary levels. Couriers start their day early, around 5:30 or 6 AM, with tasks split into morning deliveries and afternoon collections. Customer preferences, such as post-3 PM deliveries, require immediate route adjustments. While enhancing customer satisfaction, the “open-on-delivery” service can sometimes cause disputes. Couriers use specific codes to record non-delivery reasons, such as recipient absence or address changes. Challenging working hours, particularly early morning shifts (5 AM to 9 AM) and afternoon shifts (3:30 PM to 7:30 PM) from Monday to Friday, may contribute to this issue. Truck drivers mostly work at night, beginning their routes at 5 PM to reach destinations within a few hours. On busy days, couriers manage 50 to 100 deliveries along a single route. Business activity also sees seasonal dips, particularly from January 15th to March 15th. Following the involvement of a venture capital fund with the parent company, cost-cutting measures have been implemented, halting new hires and keeping salaries modest. Some companies, such as Cargus, now retain only their internal management and office staff, transferring fleet maintenance and staff salary costs to contractors. Contractors bear more responsibilities and financial burdens as a result. A strict organisational structure and rule enforcement within the parent company, such as safety protocol adherence and mandatory submission of employment documents before badge issuance, foster a disciplined work environment. HUB representatives oversee contractors and drivers, assigning specific routes, which clarifies couriers’ duties. Managing returns is a direct yet costly aspect of the business, with costs incurred when customers refuse parcels due to preference changes or insufficient funds. In this evolved operational landscape, delivery processes are complex and highly monitored. The use of Air Waybills (AWBs) and specialized software facilitates detailed tracking of shipments, recording instances of refused items or those logged at the hub. Enhanced surveillance, including video monitoring, is crucial as some packages may contain money. If a parcel is missing, it is typically found at the hub or marked as stolen, prompting an internal investigation based on that item’s last recorded system entry. Couriers reconcile the movement of goods at the end of each day, and any undelivered items are managed by the “ship and go” department, ensuring systematic handling and accountability.

Delivery company managers face multiple financial challenges, including per-kilometre expenses, rising fuel costs, delayed payments from contractors (up to 60 or 90 days), tire replacements, GPS systems, compliance and ISCIR (vehicle inspection) documentation, and service hour costs. These expenses strain their resources. There is a perceived inequity between foreign delivery companies, like those from Poland, and Romanian firms. Despite being under the same parent company, foreign entities reportedly receive better compensation. Frequent changes in venture capital ownership, often every five years, lead to managerial and staff shifts, disrupting project continuity. Local firms also bear branding costs, such as painting trucks white and displaying the parent company’s logo at their own expense, and face substantial penalties deducted from their billings. Operational costs include fuel expenses, impacted by workload and fluctuating prices, and mandatory insurance for business vehicles (RCA). Couriers can supplement their income with tips, although instances of unethical conduct, like misappropriation of collected cash, raise concerns about trust and integrity. The lack of legal action against such misconduct indicates a need for stronger monitoring and possibly stricter hiring practices.

Regarding equipment, traditional delivery operations usually employ standardized vehicles, which may vary in environmental efficiency. Lately, delivery companies have been transitioning to modern trucks with Euro 5 and Euro 6 standards, offering low fuel consumption, reduced CO2 emissions, and enhanced performance compared to older models. For operational efficiency, some companies have set up their own fuel stations at their headquarters, maintaining a certain level of cleanliness. Addressing environmental concerns, various municipalities and city areas impose traffic restrictions and higher fees on vehicles with high pollution levels, particularly those with Euro 4 engines or lower. Despite the environmental impact, many companies predominantly use diesel for their engine efficiency. However, they often have a diverse range of vehicle sizes to more effectively allocate orders, using a mix of trucks, vans, and standard vehicles. Delivery companies have recently experienced a significant shift in their operations, adopting advanced technologies to enhance their processes. This includes investment in cutting-edge tech like mobile point-of-sale (POS) systems and near-field communication (NFC) technology. Such advancements have led to a decline in cash-on-delivery transactions, once a popular payment method in Romania, helping to reduce the shadow economy and instances of unauthorized cash withdrawals.

Significant investments have also been directed towards acquiring electric vehicle fleets and installing „easy boxes” with SMS unlocking features in neighbourhoods. These initiatives aim to reduce the environmental impact and improve operational efficiency by cutting travel distances and promoting the use of eco-friendly electric vehicles. Cargus’s contractor company is committed to environmental responsibility by practising differentiated waste collection, separating materials like cardboard, paper, plastic, and glass. Various factors are considered in determining tariffs, including fuel consumption, load weight, price per kilometre, truck speed, terrain, road types, and the number of drivers involved. Despite this complexity, there is a noticeable lack of time for financial performance planning and forecasting. This is attributed to the need to adhere to pre-booked trips, truck schedules, and mandated rest hours, suggesting a more operational and potentially reactive approach to managing logistics and financial planning.

Interviews with top managers in the industry have highlighted a trend where the focus on profit often leads to neglecting quality and environmental standards. Large companies run programmes that protect the environment and people; however, companies operating on tight budgets tend to prioritise cost efficiency, sometimes at the expense of environmental responsibility and maintaining high-quality standards. This scenario underscores a common dilemma in the business world: the pursuit of profit can sometimes conflict with broader objectives such as environmental sustainability and upholding quality.

SAMEDAY, business model sustainability

Among the managers interviewed was a Sameday (Delivery Solutions SA) senior management member. As a key part of the eMAG group, Romania’s most extensive e-commerce marketplace, Sameday is a leading courier company that adopts a hybrid business strategy. It caters to about 90% of the online retail market in Romania and has significantly impacted the sector with its countrywide network of automated lockers, known as Easy boxes. These lockers have drastically reduced CO2 emissions by 95% compared to conventional delivery methods. Now, approximately 50% of Sameday’s deliveries are conducted through these boxes, enabling couriers to manage up to 500 parcels a day.

Sameday operates its own fleet in Bucharest and its surroundings while partnering with external regional entities for last-mile deliveries from their hubs. This method is particularly effective during high-demand periods like Black Friday and Christmas, emphasizing staff leasing for cost efficiency. These partners are regularly evaluated, gaining from Sameday’s expertise and adhering to strict operational standards, with their remuneration tied to key performance indicators like delivery quality, client interaction, and the number of complaints. The company heavily invests in training its couriers and affiliate agencies, referred to as the „smile team”, to maintain high customer service standards. Furthermore, Sameday conducts leadership and training programs across all levels to nurture a culture conducive to growth. Biannual customer surveys are conducted to guide its development strategies.

For optimizing last-mile deliveries, Sameday employs AI technology, integrating Google Maps and GPS data, enhanced by courier feedback, which allows continuous system improvement. On average, couriers handle 50-70 stops each day. The company also closely monitors delivery times, sorting and hub operations efficiency, and hygiene standards.

With a significant investment of 100 million euros in recent years, Sameday is moving towards financial breakeven. The company has embraced environmentally friendly practices, such as using entirely recycled plastic for packaging and switching to electronic contracts. Committed to reducing its carbon footprint, Sameday is exploring options for ESG reporting and has already invested in a fleet of 100 electric vehicles, with plans for further expansion. The company is also pioneering the development of an autonomous electric Easy box, aiming for a full transition to this innovative model.

Conclusions

The current research uncovers pronounced disparities in economic sustainability between delivery companies and other businesses in Romania, with notable variations across regions. The sector is divided between leading players and numerous microenterprises grappling with minimal economic performance. Despite their size, these microenterprises often achieve higher turnovers than some of the larger firms in the industry. Interviews with top executives indicate that outsourcing is a common strategy in the delivery sector, both in traditional and GIG courier companies, fueling the recent increase in the number of delivery companies. Rising demand for delivery services, coupled with fierce competition, has led to pricing challenges, pushing companies to reduce costs, frequently through the employment of foreign labour for its cost-effectiveness. The study also observes a trend among top delivery companies towards adopting environmentally sustainable practices, improving their economic performance and giving them a competitive advantage. Despite facing hurdles such as fluctuating fuel prices and the need for technological upgrades, delivery companies have demonstrated considerable flexibility and resilience. They efficiently utilize technology to enhance operational efficiency and incorporate eco-friendly methods, contributing to their overall economic sustainability. Navigating a fine line between technological progress and environmental responsibility, the delivery sector presents a unique opportunity to lessen its environmental impact while ensuring social and economic stability. These insights are crucial for policymakers, industry leaders, and the broader economic framework, providing direction on advancing sustainability within the delivery sector and developing a well-balanced economic ecosystem.

Acknowledgment

This paper was co-financed by The Bucharest University of Economic Studies during the PhD program.

References

- Elkington, J. (1997). Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business. Capstone.

- ro. (2023, October 16). Retrieved from www.membri.listafirme.ro.

- Malik, R., Visvizi, A., & Skrzek-Lubasińska, M. (2021). The GIG Economy: Current Issues, the Debate, and the New Avenues of Research. Sustainability, 13(9), 5023.

- SFC Support Portal. (n.d.). All companies fulfilling the definition of a micro enterprise are also small and medium, and all small are also medium. Are these categories mutually exclusive, or should a micro enterprise be counted one time per each category? SFC Support Portal. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/sfc/en/2014/support-ms/ent/faq/all-companies-fulfilling-definition-micro-enterprise-are-also-small-and.

- (2023). World population by year. Worldometers. Retrieved September 7, 2023, from https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/world-population-by-year/.