Introduction

The impact of education, or what is often called intellectual capital, on economic growth is being increasingly recognized by governments around the world. One way of accumulating and enhancing intellectual capital is to strengthen and expand the tertiary education sector. The better and superior tertiary education which contributes to productivity and growth, has been demonstrated empirically (Rowley, 2003).

While severe competition has resulted in tertiary education institutions taking cognizance of the importance of student retention, the issue has not been adequately examined empirically, and understanding what drives students to continue with the existing institution has apparently not been understood sufficiently. A more effective and conceptually sound research model to measure the effect of student satisfaction on student retention, as well as how switching barriers impact student satisfaction and retention is the primary issue addressed by this research.

Self-financed Tertiary Education Sector in Hong Kong

Providing quality education has been a priority for the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) government and it has put sustained efforts and a great deal of resources for this purpose. As the case is in most other regions in the world, Hong Kong also has government funded as well as private tertiary education institutions, which are run largely on the back of self-generated revenues, mostly fees.

Programs offered by self-financed tertiary education institutions offer both sub-degree and bachelor degree programs. Sub-degree students are generally expected to continue with the same institution for degree programs, i.e., all institutions strive to ensure that their sub-degree students are sufficiently satisfied with their respective experiences that encourage them to continue. It wouldn’t be an exaggeration to say that most of the privately managed institutions focus on sub-degree students. Thus, it is important to examine whether the institutions are able to generate a sense of loyalty among their sub-degree students, which largely determines the ability to retain students.

The self-financed tertiary education sector has grown at a very fast pace in recent years and the general feeling is that the supply of tertiary education opportunities now exceeds the demand, which means excessive competition among the self-financed institutions (Wong and Wong, 2012). As a result, sub-degree students are being offered a very large variety of choices of bachelor degree courses because all institutions try to retain them to the most extent possible. The most important and the largest source of revenue for privately managed tertiary education institutions continues to be the fees their students pay. Large running expenses are required to be incurred by self-financed institutions, including salaries of teachers and supporting staff and maintenance of infrastructure and, therefore, they have to ensure continuous recruitment of new students and retention of existing students. Like most other service industries, in education, it is a lot cheaper to retain a student than to recruit a new student and therefore self-financed institutions have to devise effective strategies to retain sub-degree students on an ongoing basis.

Theoretical Background

Providing quality educational services to students and ensuring their satisfaction is absolutely imperative for survival of self-financed tertiary education institutions in the highly scenario prevailing in Hong Kong. Since acquisition of new students for bachelor and higher programs is far more expensive than retention of sub-degree students, understanding of what makes existing students continue in the same institution for higher education is crucial for the managements of these institutions. For comprehending the reasons that make students feel satisfied and continue education in the same institution, the need for identifying the key drivers, formulation of effective strategies and implementation of clearly defined action plans cannot be over-emphasized.

Traditionally, the measurement of satisfaction of customers has been viewed as the most important part of retention of customers by corporations (Alegre and Cladera, 2009; Eshghi et al., 2007; Kandampully and Suhartanto, 2000; Streukens and Ruyter, 2004). It is necessary to have a comprehensive action plan that incorporates switching barriers to ensure customer satisfaction that actually yields the desired results (Ranaweera and Prabhu, 2003). Both customer satisfaction and barriers to switching the service provider are important drivers of customer retention and they impact customer behaviour independently, as well as in tandem with each other (Lee et al., 2001; Ranaweera and Prabhu, 2003; Wong, 2005). At many times, there are customers who are apparently satisfied with the service but deep inside have a sense of dissatisfaction. In such cases, high switching barriers are able to discourage them from opting for a new service provider. The moderating effect of switching barriers, which depends on their magnitude, impacts the correlation between customer satisfaction and customer retention.

The concepts of and the correlation between customer satisfaction and customer loyalty are explained and the importance of variables that moderate the influence of individual driving factors is explained in later sections.

Students as Customers

Self-financed tertiary education institutions constitute a business segment and they do look at students as their customers. As far back as in the 1990s, students were described, by an education institution, as customers (Crawford, 1991). So, these institutions have to worry about retaining students exactly the way any service business; like a hotel or an airline; worries about retaining its customers. Therefore, like other service businesses, self-financed tertiary education institutions also need to examine various possible ways of retaining their customers and come up with suitable management and marketing strategies (Helgesen and Nesset, 2007).

Customer Satisfaction

Several previous studies have proposed customer satisfaction as a comprehensive construct for measuring efficacy of a product or service over a period of time and studying the resultant customer experience and behaviour (Fornell, 1992; Johnson and Fornell, 1991; McDougall and Levesque, 2000 Anderson et al., 1994; Oliver, 1999). Customer satisfaction has been defined as response of a consumer in terms of fulfilment of needs and to determine whether a product or service or its features provide satisfaction with the consumption. Extant research has used the customer satisfaction construct for evaluative judgment, assessment of emotional state and a combination of both. When it is evaluative judgment, researchers have viewed customer satisfaction as an overall evaluation of satisfaction and the resultant response (Czepiel et al., 1974) while customer satisfaction has also been defined as an emotional response to purchase of specific products or services, after consumption thereof (Woodruff et al., 1983). Some researchers have considered both evaluative judgment and emotional response in the construct (Miller, 1977).

Researchers in marketing field have consistently recognized customer satisfaction as an important consideration for all kinds of businesses since it implies not only retention of customers who purchase the product or service repeatedly and spurs word-of-mouth endorsements of the same but also loyalty of customers (Anderson et al., 1994).

Customer Retention

One dimension of the customer loyalty construct which was considered, conceptualized and operationalized in extant research is customer retention (Boulding et al., 1993; Zeithamel et al., 1996). Yet, it has been examined by only a few, like Crosby and Stephens (1987), Reichheld and Sasser (1990) and Rust and Zahorik (1993). In fact, customer loyalty and customer retention have been frequently used as interchangeable, which is not right. Many researchers have equated customer loyalty with customer retention because of the inadequate clarity of the two concepts. Customer retention is a concept that actually needs to be defined more clearly (Hennig-Thurau and Klee, 1997). While retention of existing customers implies the same customer buying the product or service again, which is like repeat-purchasing behavior and brand-loyalty constructs, customer retention has somewhat different connotations. Current understanding of the customer loyalty construct incorporates both behavioral and attitudinal aspects while attitudinal aspects are not included in customer retention (Jacoby and Chestnut, 1978). Besides, emphasis in customer retention is on retaining customers, with focus on strategies and actions that lead to repetitive purchases by the same customers (Hennig-Thurau and Klee, 1997). On the other hand, customer retention constitutes the propensity and probability of a customer staying with a company in the future (Ranaweera and Prabhu, 2003).

Relationship between Customer Satisfaction and Customer Retention

Undoubtedly, customer satisfaction is the most important factor that helps build long-term relationships with customers and retain them on an ongoing basis. Some have even described money spent on ensuring customer satisfaction as akin to taking out an insurance policy since inadequately satisfied customers are quite unlikely to remain loyal during such periods (Anderson and Sullivan 1993). Several published researchers have opined that customer satisfaction is absolutely necessary for the retention of existing customers and that is why satisfaction should always be the core of relational marketing approaches (Rust and Zahorik, 1993). In extant research, customer satisfaction has been largely viewed as the most important determinant of long-term loyalty of customers (Oliver, 1980; Yi, 1990). To increase the proportion of retained customers, managing satisfaction is vital (Fornell 1992). According to Cronin and Taylor (1992) and Patterson et al., (1997) satisfaction of customers has a significant impact on their repurchase intentions in case of a wide range of services. Day et al., (1988) also found client satisfaction to be unquestionably the key determinant of customer retention in professional services. Kotler (1994) said satisfaction is the key to retention.

Notwithstanding the fact that effective management of the basic construct of customer satisfaction has become a given among those examining relationship marketing (Anderson et al., 1994; Fornell, 1992; Fornell et al., 1996), there are differences about the exact correlation between satisfaction and repurchase intentions or loyalty (Brown et al., 1993; Mitall et al., 1998; Oliva et al., 1995; Oliva et al., 1992). While the correlation between customer satisfaction and repurchase intentions is considered to be symmetrical and linear by some (LaTour and Peat, 1979), implying that satisfaction directly impacts repurchase intentions (Brown et al., 1993; Mitall et al., 1998), others believe this is asymmetrical and nonlinear (Oliver and Bearden, 1995). Some like Oliver (1993) have also posited that repurchase intention or customer loyalty does not always move positively along with satisfaction. Therefore, the probability of a customer making repeat purchases is isomorphic with neither positive nor negative service experience (Feinberg et al., 1990).

Many researchers have said categorically that customer satisfaction and customer retention are not exactly the same constructs and cannot be used interchangeably (Bloemer and Kasper, 1995; Oliver, 1999). An apparently loyal customer may or may not be a satisfied customer as loyalty may be because alternative sources of products or services are not available. Thus, there is a need for firms to comprehend the finer distinctions between the two constructs of satisfaction and loyalty, in order to ensure effective retention of existing customers. There is a room for difference in opinion on similarities, or absence thereof, between the two constructs and the assumption does invite skepticism.

Satisfaction Trap

Behavior and attitude, sort of components of loyalty, have been shown to be related to customer satisfaction by several studies (Anderson and Sullivan, 1990; Boulding et al., 1993; Cronin and Taylor, 1992; Fornell, 1992; Magi and Julander 1996; Taylor and Braker 1994; Zeithamel et al., 1996). However, continuance of customer loyalty isn’t guaranteed by satisfaction alone (Jones and Sasser, 1995) because customers too face several types of constraints when choosing suppliers and therefore satisfaction is only one of the factors that determines customer loyalty or repeat purchases (Bendapudi and Berry 1997). It is true that considerable evidence has been provided by a number of researchers to show that satisfaction does influence repeat purchase behavior but the evidence so presented has explained only a part of the intention of customers to remain loyal to the product or service (Szymanski and Henard, 2001). It is now being increasingly recognized that the correlation between customer satisfaction and customer loyalty is more complex than it was originally proposed (Garbarino and Johnson, 1999; Mittal and Kamakura, 2001; Oliver, 1999). Despite evidence of the complexity of this correlation, many continue to hold an almost myopic belief and believe that customer satisfaction and service quality are sufficient to ensure customer retention (Reichheld, 1996). Obviously, firms need to shed their obsession with this rather simplistic belief and develop a better and more comprehensive understanding of various factors that drive customer retention.

If customer satisfaction is the sole driver of a business, it can lead to a situation where the product or service is being purchased simply because the minimum performance criteria are being met, for the time being. For continuous growth in share of loyal customers in the overall sales, companies need to go beyond the basic satisfaction and build relationships that incorporate features that act as constraints to switching suppliers (Bendapudi and Berry 1997). These constraints are essentially barriers that prevent customers from opting for other sources.

Switching Barriers

A switching barrier has been defined as a factor that makes it difficult and more expensive for consumers to change service or goods providers (Jones et al., 2000). The intention to switch may be because of dissatisfaction with the current supplier and the barrier may be financial, social or psychological (Fornell, 1992). Some researchers have found that the higher the switching barrier is, the more difficult it is for the customer to switch (Kim et al., 2003). High cost and difficulties involved in switching discourage customers from moving to alternative suppliers (Jones, et al., 2000). In case of retail banking, search cost, transaction costs, learning costs, loyalty discounts and emotional costs discourage customers from switching to alternate banks (Pass, 2006; Pont and McQuilken, 2005; Sengupta, et al., 1997; Va´zquez-Carrasco and Foxall, 2006). Uncertainties about the new or alternate service provider, real or perceived, also discourage switching and these include unexpected adverse consequences of switching (Dowling and Staelin, 1994).

Moderating Effects Switching Barriers on the Satisfaction-Retention Link

There is no consistent correlation between customer satisfaction and customer retention. Much depends upon the way a provider of goods or services is positioned in the market and the structure of the market the provider is operating in. For example, in a monopoly market, switching barriers have no effect on customer retention because there is no alternative supplier to switch to. Whether the customer is satisfied or semi-satisfied or dissatisfied, unless there is an available alternative, the question of switching does not arise.

Many have posited in extant literature that loyalty to suppliers develops either because the customers want to or they have to (Hirschman, 1970; Ping, 1993). When there are high switching barriers, sometimes the alternative becomes meaningless because the cost of the switch is simply too high. In such circumstances, a dissatisfied customer also becomes loyal (Gronhaug and Gilly, 1991).

Even when clients are not satisfied with the goods or services they buy, they often continue to do so because of the costs involved in case of switching to an alternative source, or the efforts required to search for an acceptable alternative, the penalties that may have to be paid for leaving the existing supplier or the loss of incentives that have been accumulated because of a long relationship and of course the risk of the new supplier not providing the expected or promised level of satisfaction. The impact of switching barriers on customer loyalty even when the satisfaction is less than what is expected has been explained by many, including Jackson (1985). Thus, successful customer retention by a firm may be attributable to either satisfaction or relatively high switching barriers. Conversely, customers can leave because of either real and substantial dissatisfaction or due to low switching barriers which do not hinder spur of the moment decisions and make it easy to change providers.

Conceptual Research Model

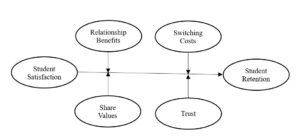

The correlation between customer satisfaction and customer retention is obviously quite intricate and complex. Switching barriers that can effectively moderate this relationship, specifically in self-financed tertiary education institutions in Hong Kong, need to be examined. Figure 1 (based on extant research) depicts the direct relationship between satisfaction and student retention and how switching barriers moderate or affect it.

Figure 1: Proposed Conceptual Research Model

Moderating Effect of Relationship Benefits

It was Bitner (1995) who conceptualized four types of benefits of maintaining the relationship with the existing supplier. Switching does not help reduce stress, simplify the daily life, help enjoy the given social support system and eliminate the need to change. Once a customer is familiar with the supplier and the service, he/she can correctly anticipate the quality of service and feel comfortable about the service provider. Therefore, the customer does not feel the stress associated with looking for an alternative and the incumbent uncertainties.

Morgan and Hunt (1994), Adidam et al., (2004) and Holdford and White (1997) found that relationship benefits do impact retention of students in public tertiary education institutions in the United States. Another researcher; Adidam et al., (2004) found that business students were continuing their relationships with their existing school because their benefits were superior in respect of quality of education, location of the institution, cost of tuition, opportunities for internship and placements and networking opportunities. The simple logic is when students reap high benefits from the relationship, they feel committed to the institution. Holdford and White (1997) also reached similar conclusions after examining the relationship between a pharmacy school and its students. Therefore, it is proposed that the first moderating effect is:

For a given level of student satisfaction, the higher is the level of perceived relationship benefits the higher is student retention.

Moderating Effect of Switching Costs

Cost of switching is one type of switching barrier (Colgate and Lang, 2001; Burnham et al., 2003; Wathne et al., 2001). Quite often, the cost is defined more in terms of perceptions of customers, rather than an actual cost since some customers may add the cost of time to be likely spent on finding an alternative also (Porter, 1980). Burnham et al., (2003) have defined three components of switching costs, procedural (cost of evaluation and cost of time and effort required therefore) costs, financial (any benefits one may lose and any fees one may have to pay to the new provider) costs and relational (any conveniences one may be enjoying with the existing provider because of the relationship, assuming the relationship which has to be built again at the new provider, for the same degree of convenience) costs.

Relationships between business schools and their students were examined by Adidam et al., (2004) and they concluded that perceived losses, financial, emotional and time likely to be incurred because of discontinuance of the relationship function as a barrier to switching in their case. These losses include monetary as well as non-monetary losses such as the loss of friendships or credits if they switch to another educational institution. The general perception is that the non-monetary losses cannot be recovered after switching to another education institution. Their overall conclusion was that switching costs do encourage commitment to the existing institutions in western public tertiary education institutions. Therefore, the second moderating effect is:

For a given level of student satisfaction, the higher the level of perceived switching costs, the higher the level of student retention.

Moderating Effect of Shared Values

In services industry, the degree of commonality between perceptions and thinking of the customer and the service provider is an important factor. When both perceive certain components of the service as important or not important or wrong or right, that leads to higher satisfaction or at least less dissatisfaction on the part of the customer. A high degree of commonality between perceptions of the two sides also helps them communicate with each other in a more effective way, thereby; avoiding or minimizing the occurrence of misunderstandings (Morgan and Hunt, 1994, p. 25; Tsai and Ghoshal, 1998; and Levin, 2004).

When the two sides agree on what constitutes appropriate behaviors, what are the right goals and what should be the effective policies, the probability of higher commitment to the relationship strengthens (Morgan and Hunt, 1994; Holdford and White, 1997; Adidam et al., 2004). Holdford and White (1997) examined the relationship between a pharmacy school and its students and found that when students believed in the same goals, ideals and codes of conduct as the schools were, they were more willing to commit to a relationship with the school. Similar findings have been reported by Adidam et al., (2004) who found that when the staff and business students have similar concerns and ideas on an issue such as workload, learning behavior and assessments, the students are relatively more committed to the relationship. Therefore, the third moderating effect is:

For a given level of student satisfaction, the higher the level of perceived shared values, the higher the level of student retention.

Moderating Effect of Trust

Several psychology, sociology and economics studies have defined trust as reliability of words and promises of either party about intents and expectations of events (Rotter, 1967; Deutsch, 1958; and Gambetta, 1988). Like many other common constructs, definition of trust too has evolved over time, after myriad interpretations (Crosby et al., 1990; Moorman et al., 1992; Morgan and Hunt, 1994). Morgan and Hunt (1994, p. 23) said “when one party has confidence in an exchange partner’s reliability and integrity” there is trust between the two. A high level of integrity and competence, consistence, fairness, honesty, responsibility, helpfulness and benevolence are different aspects and components of trust.

The Morgan and Hunt (1994), Hennig-Thurau et al., (2001), Holdford and White (1997) and Adidam et al., (2004) have presented contours of the relationship between students and educational institutions that conceptualize trust as confidence in reliability and integrity of the partner. These researchers have based their findings on personal experiences of individual students with their educational institutions and found that trust affects student retention by public tertiary education in a significant manner. Therefore, the fourth moderating effect is:

For a given level of student satisfaction, the higher the level of perceived trust, the higher the level of student retention.

Conclusions

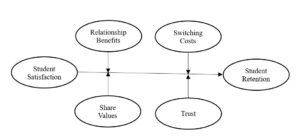

This research proposes a research model to ascertain the effects of student satisfaction on student retention, besides the moderating effect of switching barriers on the relationship. Moving beyond the traditional research on the relationship between student satisfaction and student retention, it is suggested that once students are recruited, it is logical to erect switching barriers, to retain them (Figure 2). Switching barriers of different kinds and magnitude do impact the relationship between student satisfaction and student retention. Switching barriers have different effects on individual students and therefore, on the effect of satisfaction on student retention also. Future research may collect and examine empirical evidence to support the claims of this study. Other moderating variables that operate in particular contexts may need to be incorporated. More moderators of the relationship may need to be identified.

Figure 2: Student Recruitment – Switching Barriers Strategies – Student Retention Link

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

References

- Adidam, P.T., Bingi, R.P. and Sindhav, B., 2004. Building relationships between business schools and students: an empirical investigation into student retention. Journal of College Teaching and Learning, 1(11), pp.37-48.

- Anderson, E. and Sullivan, M.W., 1993. The antecedents and consequences of customer satisfaction for firms. Marketing Science, 12(2), pp.125-145.

- Anderson, E.W., Fornell, C., and Lehmann, D.R., 1994. Customer satisfaction, market share, and profitability: findings from Sweden. Journal of Marketing, 58(3), pp.53-66.

- Anderson, J.C. and Narus J.A., 1990. A model of distributor firm and manufacturer firm working partnerships. Journal of Marketing, 54(1), pp.42-58.

- Bendapudi, N. and Berry, L., 1997. Customer’s motivations for maintaining relationships with service providers. Journal of Retailing, 73(1), pp.15-38.

- Bitner, M.J., 1995. Building service relationships: its all about promises. Journal of Academy of Marketing Science, 23(4), 246-251.

- Bloemer, J.M.M. and Kasper, H.D.P., 1995. The complex relationship between consumer satisfaction and brand loyalty. Journal of Economic Psychology, 16(2), pp. 311-329.

- Boulding, K.D., Kalbra, A., Staeling, R. and Zeithaml, V.A., 1993. A dynamic process model of service quality: from expectations to behavioral intentions. Journal of Marketing Research, 30(2), pp.7-27.

- Brown, T.J., Churchill, G.A. and Peter, J.P., 1993. Improving the measurement of service quality. Journal of Retailing, 69(1), pp.127-139.

- Burnham T.A., Frels J.K., and Mahajan V., 2003. Consumer switching costs: a typology, antecedents, and consequences. Journal of Academy of Marketing Science, 31(2), 109-126.

- Colgate, M. and Lang, B., 2001. Switching barriers in consumer market: an investigation of the financial services industry. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 18(4), pp.332-347.

- Crawford, F., 1991. Total quality management. committee of vice-chancellors and principals. London: Occasional paper.

- Cronin, J.J. and Taylor, S.A., 1992. Measuring service quality: a reexamination and extension. Journal of Marketing, 56(3), pp.55-68.

- Crosby L.A., Evans K.R. and Cowles D., 1990. Relationship quality in services selling: an interpersonal influence perspective. Journal of Marketing, 54(3), 68-81.

- Crosby, L.A. and Stephens, N., 1987. Effects of relationship marketing on satisfaction, retention, and prices in the life insurance industry. Journal of Marketing Research, 24(4), pp.404-411.

- Czepiel, J.A., Rosenberg, L.J. and Akerele, A., 1974. Perspectives on consumer satisfaction, proceedings. Chicago: American Marketing Association.

- Day, E., and Denton, L. L., and Hickner, J. A. (1988), Clients’ selection and retention criteria: some marketing implications for the small CPA firm, Journal of Professional Services Marketing, 3(4), pp. 85-91.

- Deutsch M., 1958. Trust and suspicion. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 2(4), 265-279.

- Dowling, G. and Staelin, R., 1994. A model of perceived risk and intended risk-handling activity. Journal of Consumer Research, 21(1) , pp.119-34.

- Feinberg, R.A., Widdows, R., Hirsch-Wyncott, M. and Trappey, C., 1990. Myth and reality in customer service: good and bad service sometimes leads to re-purchase. Journal of Consumer satisfaction, Dissatisfaction, and Complaining Behaviour, 3, pp.112-114.

- Fornell, C., 1992. A national customer satisfaction barometer: the Swedish experience. Journal of Marketing, 56(1), pp.1-18.

- Fornell, C.M.D., Johnson, E.W., Anderson, J.C. and Bryant, B.E., 1996. The American customer satisfaction index: nature, purpose, and findings. Journal of Marketing, 60(4), pp.7-18.

- Gambetta D., 1988. Can we trust trust? trust: making and breaking cooperative relations. New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

- Garbarino E. and Johnson M.S., 1999. The different roles of satisfaction, trust, and commitment in customer relationships. Journal of Marketing, 63(2), 70-87.

- Gronhaug, K. and Gilly, M.C., 1991. A transaction cost approach to customer dissatisfaction and complaint actions. Journal of Economic Psychology, 12(1), pp. 165-83.

- Helgesen, O and Nesset, E., 2007. What account for student’s loyalty? some field study evidence. International Journal of Educational Management, 21(2), pp.126-143.

- Hennig-Thurau T,T., Langer, M.F. and Hansen, U., 2001. Modeling and managing student loyalty. Journal of Services Research, 3(4), pp.331-344.

- Hennig-Thurau, T. and Klee, A., 1997. The impact of customer satisfaction and relationship quality on customer retention: a critical reassessment and model development. Psychology and Marketing, 14(8), pp.737-764.

- Hirschman, A.O., 1970. Exit, voice and loyalty responses to declines in firms, organizations and states. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Holdford D. and White S., 1997. Testing commitment-trust theory in relationships between pharmacy schools and students. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 61(2), 249-256.

- Jackson, B.B., 1985. Build customer relationships that last. Harvard Business Review, 12, pp.120-128.

- Jacoby, J. and Chestnut R. B., 1978. Brand loyalty measurement and management. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

- Johnson, M.D. and Fornell, C.,1991. A framework for comparing customer satisfaction across individual and product categories, Journal of Economic Psychology, 12(2), pp.267-286.

- Jones, M.A. and Suh, J., 2000. Transaction-specific satisfaction and overall satisfaction: an empirical analysis. Journal of Service Marketing, 14(2), pp.147-159.

- Kotler, P., 1994. Marketing management. analysis, planning, implementation, and control. 8th ed. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

- LaTour, S. A. and Peat, N. C. 1979. Conceptual and methodological issues in consumer satisfaction research. Advances in Consumer Research, 6, pp.431-437.

- Lee, J., Lee, J., and Feick, L. 2001. The impact of switching costs on the customer satisfaction-loyalty link: mobile phone service in France. Journal of Services Marketing, 15(1), pp.35-48.

- Levin D.Z., 2004. Perceived trustworthiness of knowledge sources: the moderating impact of relationship length. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(5), pp.1163-1171.

- Magi, A. and Julander, C.R., 1996. Perceived service quality and satisfaction in a store profit performance framework: an empirical study of Swedish grocery retailers. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 3(1), pp.33-41.

- Miller, J.A., 1977. Studying satisfaction: modifying models, eliciting expectations, posing problems and making meaningful measurements, In Hunt, H.K. (ed.) Conceptualization and Measurement of Consumer Satisfaction and Dissatisfaction, Bloomington: School of Business, Indiana University, pp.72-91.

- Mitall, V., Rose, W.T. and Baldasare, P.M., 1998. The asymmetric impact of negative and positive attribute-level performance on overall satisfaction and repurchase intentions. Journal of Marketing, 62(1), pp.33-47.

- Mittal, V. and Kamakura, W.A., 2001. Satisfaction, repurchase intent, and repurchase behavior: investigating the moderating effect of customer characteristics. Journal of Marketing Research, 38(1), pp.131-142.

- Moorman C., Zaltman G. and Deshpande R., 1992. Relationships between providers and users of marketing research: the dynamics of trust within and between organizations. Journal of Marketing Research, 29(3), 314-329.

- Morgan R.M. and Hunt, S.D., 1994. The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing, 58(3), pp.20-38.

- Oliva, T.A., Oliver, R.L. and Lan, C. M., 1992. A catastrophe model for developing service satisfaction strategies. Journal of Marketing, 56(3), pp.83-95.

- Oliver, R.L., 1993. Cognitive, affective, and attribute bases of the satisfaction response. Journal of Consumer Research, 20(3), pp.495-507.

- Oliver, R.L., 1999. Whence consumer loyalty. Journal of Marketing, 63(4), pp.33-44.

- Patterson P.G., Johnson L.W., and Spreng R.A., 1997. Modeling the determinants of customer satisfaction for business-to-business professional services. Journal of Academy of Marketing Science, 25(1), 4-17.

- Porter M.E., 1980. Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors. New York: Free Press.

- Ranaweera, C. and Prabhu, J., 2003. The influence of satisfaction, trust and switching barriers on customer retention in a continuous purchasing setting. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 14(4), pp.374-395.

- Reichheld F.F., 1996. The loyalty effect. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

- Reichheld, F.F. and Sasser, W. E., 1990. Zero defections: quality comes to services. Harvard Business Review, 68(5), pp.105-111.

- Rotter J.B., 1967. A new scale for the measurement of trust. Journal of Personality, 35(4), 651-655.

- Rust, R.T. and Zahorik, A.J., 1993. Customer satisfaction, customer retention, and market share. Journal of Retailing, 69(2), pp.193-215.

- Swan, J.E., 1988. Consumer satisfaction related to disconfirmation of expectations and product performance. Journal of Consumer Satisfaction Dissatisfaction, and Complaining Behavior, 1, pp.40-47.

- Szymanski, D.M. and Henard, D.H., 2001. Customer satisfaction: a meta-analysis of the empirical evidence. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 29(1), pp.16-35.

- Taylor, S.A. and Baker, T.L., 1994. An assessment of the relationship between service quality and customer satisfaction in the formation of consumers’ purchase intentions. Journal of Retailing, 70(2), pp.163-178.

- Tsai W. and Ghoshal S., 1998. Social capital and value creation: the role of intrafirm networks. Academy of Management Journal, 41(4), 464-476.

- Vazquez-Carrasco, R. and Foxall, G.R., 2006. Influence of personality traits on satisfaction, perception of relational benefits, and loyalty in a personal service context. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 13(3), pp.205-219.

- Wathne K.H., Biong H. and Heide J.B., 2001. Choice of supplier in embedded markets: relationship and marketing program effects. Journal of Marketing, 65(2), 54-66.

- Wong, C.B. and Wong, K.L., 2012. The moderating effect of switching barriers: online stock and derivatives trading. GSTF Business Review, 2(2), pp.245-251.

- Woodruff, R.B., Cadotte, E.R. and Jenkins, R.L., 1983. Modeling consumer satisfaction processes using experience-based norms. Journal of Marketing Research, 20(3), pp.296-304.

- Zeithaml V.A., Berry L.L. and Parasuraman A., 1996. The behavioral consequences of service quality. Journal of Marketing, 60(2), 31-46.