Introduction

The tourism sector is one of the most important economic sectors, both for the developed countries and developing countries. This sector has features such as globalization of tourism market, mobility of tourists and abundance of information. Also, all these features characterize an information society.

Tourists could be from all nations, social classes, and professions. The tourism sector is diverse, because the size of the companies that make up this sector ranges from micro, medium, to global companies (Buhalis & Jun, 2011).

Tourism is acknowledged to be very information intensive. Tourists need information before going on a trip to help them plan and choose between options, and also increasingly need information during the trip as the trend towards more independent travel increases. But for this it is necessary that the information be available and the tourism professionals with the capabilities to solve the problems.

Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) have been transforming tourism globally. The ICT driven re-engineering has gradually generated a new paradigm-shift, altering the industry structure and developing a whole range of opportunities and threats.

The introduction and increased proliferation of technologies has had a significant impact on many industries, especially the tourism sector (Ukpabi & Karjaluoto, 2016); (Morais, et al., 2016). Technological advancements have impacted and disrupted all tourism organizations (Sigala, 2018). The increased awareness and use of innovative technologies, have changed travel behaviours, revolutionizing the way in which tourists search for information, make decisions (Wang, et al., 2016), purchase tourism products and services, find and explore reviews (Ukpabi & Karjaluoto, 2016). In addition, Sigala (2018) identified tourism technologies have had an impact on the way tourists select, evaluate, pay, share and experience tourism.

People are a critical dimension within the successful delivery of tourism services. ‘‘The story of successful tourism enterprises is one that is largely about people – how they are recruited, how they are managed, how they are trained and educated, how they are valued and rewarded, and how they are supported through a process of continuous learning and career development’’ (Fáilte, 2005).

This paper aims to analyze the relevance given by the various Portuguese and Spanish institutions of higher education to ICT in their Tourism degrees. The analysis carried out was done in degree courses operating in the school year 2018/2019, in Portuguese and Spanish universities and polytechnics, public and private. It was made a comparison to a study carried out in the school year 2012/2013 (Morais, et al., 2013) in order to see the evolution.

Tourism Education and ICT

The adoption and diffusion of educational technologies that leverage ICT and the Internet has provided an unprecedented opportunity for improving higher education around the world (Davis & Wong, 2007). Educational technologies must become more popular among developing nations which seek economic improvement (Khasawneh, et al., 2011). In fact, the educational technology is becoming more universal at an increasing rate as most firms recognize the needs to prepare the ICT professionals for the global environment (Margavio, et al., 2005).

People are critical assets within the tourism industry for sustaining and enhancing competitiveness and quality. The involvement of the training and education sectors to industry is vital. Good management in service organizations and tourism enterprises certainly qualify as strategic success factors of the industry (Heskett, et al., 2008).

Higher education drives and is driven by globalization. Higher education institutions train the highly skilled workforce and contribute to the research base and innovation capacity that increasingly determines competitiveness in a knowledge-based global economy. With their central role in cross-cultural encounters, Higher education institutions foster mutual understanding and helps to build global networks for the future. At the same time, cross-border flows of ideas, students, faculty and financing, coupled with developments in information and communication technologies, as well as the emergence of new players, are changing the environment for higher education. Globalization implies both increased collaboration and competition between countries and institutions on a global scale (OCDE, 2009).

In all the discussion forums of tourism jobs, Informatics and use of Information Technology appears as one of the most desirable skills for the future professional. Ramos et al (2009) argue that competitiveness and exploitation of the tourism industry increasingly depends on the ability of professionals and managers to take advantage of the emerging ICT to increase competitive benefits, since ICT allows adding value by facilitating the differentiation of the tourism product and increasing efficiency.

One of the fundamental challenges facing tourism professionals is the need for continuous adaptation to changes, due to the dynamism of the sector (Pilar, 2007). It is through the training of human resources in the tourism industry, especially in ICT, which improves their ability to adapt and consequently is increased flexibility and interactivity productive processes which result to be increasingly complex, due to the competitiveness and globalization currently existing (Buhalis & Law, 2008). The improvement in the training of professionals will greatly increase both the quality of services provided to customers, and the level of quality of information provided to customers.

At the present moment, the basic objective is the formation of a quality specialist in the field of tourism, able to adapt quickly to the environment changes, ready for practical activity, able to use modern technologies, to find flexible and optimal solutions, to identify influences of the external environment on the company’s work and be able to forecast the demand (Lungu, 2017). We agree with this and also that without training in ICT these goals will be difficult to achieve.

Joaquim Majó (2004) does, for some time, highly relevant considerations regarding higher education in Tourism and particularly on ICT.

Even before the Bologna process, there were authors who argued that degrees in tourism beyond the pure ICT content should contain other topics, such as: Information Systems; Database Systems; Use of CRS (Central Reservation System) and GDS (Global Distribution System); Systems to promote tourism (multimedia environments); Telematics networks: Internet (both as a source of information as a means of promotion and marketing through web pages); Local networks, use of intranets and extranets; Analysis of the main management programs of tourist companies (both at the front-office and back-office); Geographic Information Systems.

(Buhalis, 1998) and (Majó, 2004) argue that this type of training should cover between 15-30% of the dedication of the student.

People are often a critical dimension within the successful tourism service businesses. The history of successful businesses in the tourism sector resides above all about people, how they are recruited, how they are managed, trained, educated, the way they are valued and rewarded and how they will be supported through a process (Fáilte, 2005); (Baum, 2007).

The impact of ICT on tourism has altered the way tourist services are accessed and consumed. Thanks to increasingly ubiquitous and innovative ICT, new channels have been created for consumers (Liburd & Christensen, 2013). This new reality has made it much more demanding for tourism professionals to master the use of these new tools. Preparing students for trainings in the area of higher education tourism is, in our view, more and more important, as ICT innovation has increasingly technologically strengthened the profile of travelers. Projects such as INNOTUR and the use of Web 2.0 technologies are an example of a concern to prepare students, from training in the area of higher education tourism, to an increasingly global and technologically demanding work reality (Morais, et al., 2018).

Methodology

The nature of the objectives led to a methodology of quantitative research, descriptive and interpretative eminently possible that characterizes the object of study. The study focused on the analysis of ICT training courses in tourism, because we believe ICT, especially in the context of the Bologna process, as basilar course units in curriculum structure, and are fundamental to the development and innovation of tourism.

The research of the courses for this study was based on the website of the Directorate General of Higher Education (http://www.dges.gov.pt/) in the case of Portugal and the State Department of Education for Spain (http://www.mecd.gob.es). We considered only the courses that had “Tourism” or “Tourist” in their name or derived (e.g. “ecotourism”, “touristic”). After collecting the courses available in the academic year 2018/2019, the remaining data were obtained through the consultation of the information available on the websites of the different institutions. For each tourism course, we considered the course units with a name and/or content (the latter not always available) that suggested references to ICT, like “information systems”, “computer”, “technology”, “electronic”, “digital”, among others. We did not consider non-ICT related course units that, eventually, could promote the development of students’ ICT skills by indirect means, since the available data don’t allow inferring that.

It was also made a comparison with a similar study developed in 2012/2013.

Analysis of Data Obtained

From the analysis, it was found that in the Portuguese higher education 50 degrees in tourism (in 2012/2013 there were 39), with 16 different designations (in 2012/2013 there were 10), distributed by 36 higher education institutions (15 on Private Higher Education and 21 on Public Higher Education). In 2012/2013, of the 39 degrees, 3 were after working hours and the remaining 36 had normal arrangements. In 2018/2019, of the 50 degrees, 6 are after working hours.

When data from the Spanish higher education was analyzed, it was verified that there are 73 degrees in the area of tourism (in 2012/2013 there were 67), with 10 different designations, distributed by 50 Higher Education institutions. The term “Tourism” is predominantly utilized (there are 62 degrees with that designation). When the education subsystem in Spain was analyzed, it was found that 61 degrees are on the Public subsystem and 12 degrees are on the Private subsystem (in 2012/2013 there were 53 on the Public subsystem and 14 were on the Private subsystem).

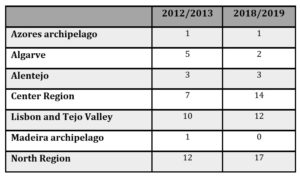

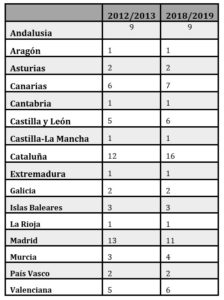

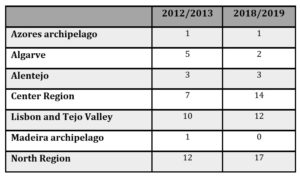

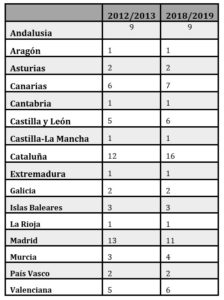

The geographical distribution of courses by NUTS II, to Portugal, and communities, to Spain, are represented in Table 1 and Table 2, respectively.

We can verify that in Spain the changes were not significant. In Portugal, there was an increase of degrees in the North region and in the Center region.

Table 1: Degrees distribution in Portugal, by NUTS II

Table 2: Degrees distribution in Spain, by communities

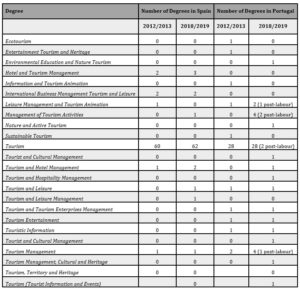

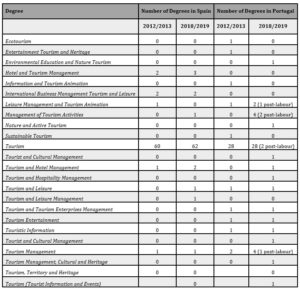

Table 3 shows the different designations and number of respective degrees, for the school year 2012/2013 and 2018/2019 both for Spain and for Portugal.

It is interesting to note that Portugal, despite having fewer degrees, has more different designations. However, in both countries the predominant designation is “tourism”, as it would be expected. In both countries there is a higher concentration of degrees in areas where the population is more abundant.

Table 3: Number of degrees in Tourism scientific area (2012/2013 and 2018/2019)

In the Portuguese case, it has been verified that in a relatively short space of time there have been significant changes, particularly in degrees whose designation is not only “Tourism”, which proves that it is a dynamic area, and intends to respond to a market that has come growing.

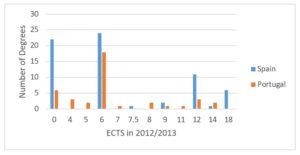

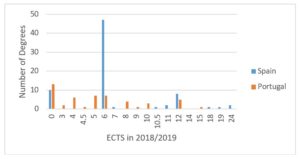

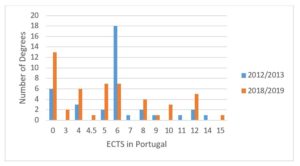

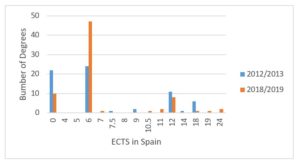

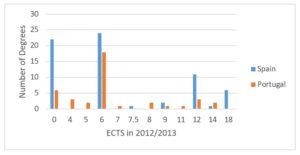

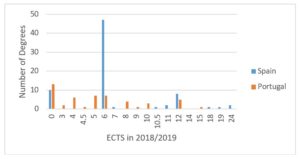

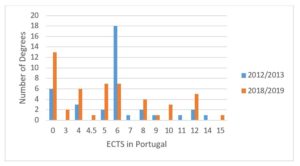

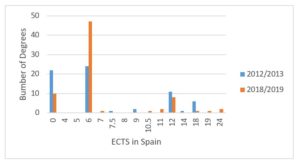

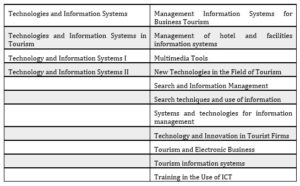

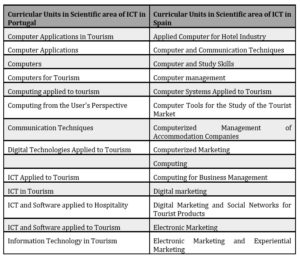

Figures 1, 2, 3 and 4 show the number of ECTS (European Credit Transfer System) in the ICT area, and the number of degrees with the corresponding ECTS in Portugal and Spain for the school year 2012/2013 and 2018/2019.

Figure 1: Comparison of Number of ECTS by Degree in Portugal and Spain (2012/2013)

Figure 2: Comparison of Number of ECTS by Degree in Portugal and Spain (2018/2019)

Figure 3: Evolution of Number of ECTS by Degree in Portugal between 2012/2013 and 2018/2019

Figure 4: Evolution of Number of ECTS by Degree in Spain between 2012/2013 and 2018/2019

In 2012/2013, Spain had 22 degrees without any curricular unit of the ICT area, while Portugal had only 6. This trend has reversed in 2018/2019. Spain has reduced the number of degrees without ICT curricular units to 10, while Portugal has increased this number to 13. With 6 ECTS, Portugal had 18 degrees in 2012/2013, also decreasing this number to 7. In contrast, Spain had 23 degrees with 6 ECTS, increasing this value to 47. There is a positive trend in the adoption of curricular units of the ICT area in Spain, while in Portugal the number of ECTS in the area of ICT in the degrees of the Tourism area has been decreasing.

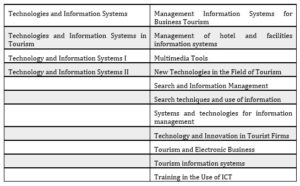

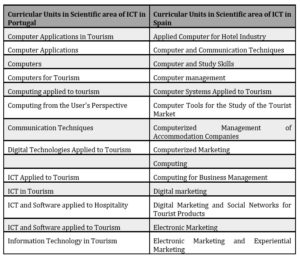

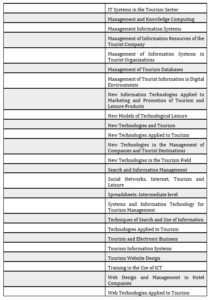

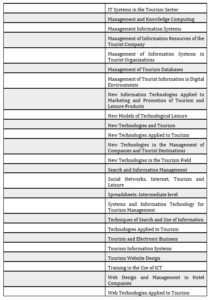

Tables 4 and 5 show the curricular units of the ICT area existing in the school years 2012/2013 and 2018/2019 for the two countries.

Table 4: Curricular Units in scientific area of ICT in 2012/2013

Table 5: Curricular Units in scientific area of ICT in 2018/2019

It was verified that in Spain there were significant changes in the curricula with regard to ICT, and there was a concern with emerging issues in technology, namely in terms of digital promotion, digital marketing, Web, Internet and Social Networks. In Portugal, there were no major changes in curricula since 2012/2013.

Institutions have their study plans available on their websites; however, when someone intends to analyze the detailed contents of the program curricular units that are part of the curriculum, in many cases the institutions do not have that information available. It was a problem detected in the analysis carried out in 2012/2013 and after six years this failure persists.

From the information we were able to collect from the institutional websites we could verify that, as expected, there is a great diversity of ICT contents in the courses, with different subjects addressed and with different levels of specialization. For example, there are courses with 18 ECTS of ICT curricular units, of which 12 are exclusively for Geographic Information Systems, while in other courses with the same name (Tourism) that topic does not even seem to deserve a topic on the syllabus.

Some of the most frequent topics are related to the main management programs of tourist companies, like Central Reservation System (CRS), Global Distribution System (GDS) and Property Management Systems (PMS), as well as topics related to e-commerce and e-business.

Curiously, smartphones, being an essential tool of today tourists, it is worthy to mention that mobile systems and technologies are not one of the most referenced topics.

Table 6 shows an overview of the ICT related topics found in the analysed tourism curses. The data are shown without any particular order and some of the topics are only mentioned in a few courses while others are more frequent.

Table 6: ICT related topics in tourism courses

Discussion and Conclusions

This paper shows values related to ICT, and the weight that the curricular units of ICT have in the plans for undergraduate studies in the tourism sector in the Iberian Peninsula (Portugal and Spain), and concluded that on average, curricular units of ICT have an insignificant representation of the ECTS in Tourism degrees, and not 15% – 30% as some authors argue that it should be (Buhalis, 1998; Majó, 2004).

The maximum number of ECTS in Portugal was 14 in 2012/2013 and 15 in 2018/2019 (around 8%). In Spain in 2012/2013 it was 18 and 24 in 2018/2019. However, they are isolated cases and still far below desirable.

In most cases, the courses have a curricular unit in the ICT area, where practically address office tools. In 2012/2013, some courses do not have any curricular unit of ICT area (6 in Portugal and 22 in Spain, which corresponds to 15% and 33%, respectively, of the courses). In the hope that the data for the 2018/2019 school year would be more prosperous with regard to ICT, we have seen that in Portugal the situation has not improved and it has also worsened. There were 13 degrees without any curricular unit of the ICT area, which corresponds to 26% of the total of degrees. Spain had 22 degrees without any UC for the school year 2012/2013 from the ICT area and decreased to 10 in 2018/2019, although the number of degrees has increased.

Increasingly, ICT plays a critical role for the competitiveness of tourism organizations and destinations becoming a key factor (Bethapudi, 2013). “A profession, no less than a craft, is shaped by its tools” (Farkhondehzadeh , et al., 2013). When we find that the evolution of the tourism industry has been principally on the ICT, in our opinion, the courses should be redesigned in order to enhance professionals with more and better skills in ICT. According to Adeyinka-Ojo (2018), ICT skills are among the necessary skills to improve graduate employability. Also, Kim et. al (2017) refer that specific competencies of the work indicate the student’s ability to apply and use information in a specific context and their knowledge about ICT. This emphasizes the need to align the graduated ICT know-how with the increasing technology wave that is flowing into the tourism industry.

With ICT, it is possible to reduce the direct costs of operation, as well as to increase the flexibility, interactivity, efficiency, productivity and competitiveness of organizations, and this situation is valid both for companies and for tourist destinations. The advantages that ICT have brought to the area of Tourism are widely recognized. To train professionals in the area of Tourism with skills and abilities in the field of ICT, it seems to us urgent. However, due to the analysis of the degree programs in this area, we found that many institutions are not training professionals with these skills. This will conduct to ICT less prepared tourism-professionals, that will embrace the tourism industry, which is very demanding in the use of ICT and, in our opinion, even worst, will tendentiously lead to professionals less capable to create value through innovation in a very information demanding market, where the target (i.e. tourists) are requiring for new tools and innovative approaches in the before, during and after their trips process.

Most of the courses do not prepare their students in order to acquire skills in the area of Geographic Information Systems, Multimedia, Augmented Reality, Digital Marketing, Social Networks, among others, especially in Portugal. In Spain, emerging themes in the ICT area, began to be addressed in the degrees analyzed in the school year 2018/2019.

Given to the recent, and expectable continuous, introduction of ICT on tourism industry, tourism related courses must improve their curricula on ICT skills. This can be achieved changing the current mandatory ICT curricular unities, increasing the optional ones related to ICT and even increasing the seminars dedicated to ICT and how they can boost graduated capabilities to improve organizations through their ability to manage information as organizational critical success factor.

Acknowledgements

UNIAG, R&D unit funded by the FCT – Portuguese Foundation for the Development of Science and Technology, Ministry of Science, Technology and Higher Education. UIDB/04752/2020.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

References

- Adeyinka-Ojo, S., 2018. A strategic framework for analysing employability skills deficits in rural hospitality and tourism destinations. Tourism Management Perspectives, Volume 27, pp. 47-54.

- Baum, T., 2007. Human resources in tourism: Still waiting for change. Tourism Management, 1384-1399.

- Bethapudi, A., 2013. The Role of ICT in Tourism Industry. JOURNAL OF APPLIED ECONOMICS AND BUSINESS, Volume 1 (4), pp. 67-79.

- Buhalis, D., 1998. Information Technologies in tourism: Implications for the tourism curriculum. Istanbul, s.n.

- Buhalis, D. & Jun, S., 2011. International centre for tourism and hospitality. [Online]

Available at: http://www.goodfellowpublishers.com/free_files/fileEtourism.pdf

[Accessed 9 12 2015].

- Buhalis, D. & Law, R., 2008. Progress in information technology and tourism management: 20 years on and 10 years after the Internet—The state of eTourism research. Tourism Management, Volume 29, p. 609–623.

- Davis, R. & Wong, D., 2007. Conceptualizing and Measuring the Optimal Experience of the eLearning Environment. Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education, 5(1), pp. 95-126.

- Fáilte, I., 2005. A human resource development strategy for Irish Tourism. Dublin, Fáilte Ireland.

- Farkhondehzadeh , A., Reza Robat Karim;, M., Roshanfekr, M. & Azizi, J., 2013. E-Tourism: The role of ICT in tourism industry. European Online Journal of Natural and Social Sciences.

- Heskett, J. L., Sasser, W. E. & Wheeler, J., 2008. Ownership Quotient: Putting the Service Profit Chain to Work for Unbeatable Competitive Advantage. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

- Khasawneh, A., Khasawneh, M., Bsoul, M. & Idwan, S., 2011. Models for Using Internet Technology to Support Flexible E-Learning. J. Management in Education.

- Kim, N., Park, J. & Choi, J.-J., 2017. Perceptual differences in core competencies between tourism industry practitioners and students using Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP). Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education, Volume 20.

- Liburd, J. J. & Christensen, I.-M. F., 2013. Using web 2.0 in higher tourism education. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education, 12(1), pp. 99-108.

- Lungu, E., 2017. THE TRAINING OF PROFESSIONAL SKILLS IN STUDENTS FROM TOURISM DOMAIN. Series IX: Sciences of Human Kinetics, 10(59), pp. 89-95.

- Majó, J., 2004. Las Tecnologías de la Información y las Comunicaciones. Malaga, TuriTec 2004.

- Margavio, T., Hignite, M., Moses, D. & Margavio, G., 2005. Multicultural Effectiveness Assessment of students in IS Courses. Journal of Information Systems Education, 16(4), pp. 421-428.

- Morais, E. P., Cunha, C. R. & Gomes, J. P., 2013. The information and Communication Technologies in Tourism Degree Courses: the Reality of Portugal and Spain. Journal of e-Learning and Higher Education, Volume 2013.

- Morais, E. P., Cunha, C. R. & Gomes, J. P., 2018. The information and communication technologies in tourism degree courses — The Portuguese evolution. Caceres, AISTI, pp. 1-6.

- Morais, E. P., Cunha, C. R., Sousa, J. P. & Santos, A., 2016. Information and communication technologies in tourism: challenges and trends.. Milan, IBIMA, pp. 1381-1388.

- OCDE, 2009. Higher Education to 2030, Volume 2: Globalisation, l.: OCDE.

- Pilar, M. L., 2007. Posibilidades profesionales de los Diplomados de Turismo. Cuadernos de Turismo, Volume 20, pp. 131-151.

- Ramos, C., Rodrigues, P. & Perna, F., 2009. Sistemas e Tecnologias de Informação no Sector Turístico. Revista Turismo & Desenvolvimento, Volume 12, pp. 21-32.

- Sigala, M., 2018. New technologies in tourism: From multi-disciplinary to anti-disciplinary advances and trajectories. Tourism Management Perspectives, Volume 25, pp. 151-155.

- Ukpabi, D. C. & Karjaluoto, H., 2016. ‘Consumers’ acceptance of information and communications technology in tourism: A review. Telematics and Informatics, 618-644.

- Wang, D., Xiang, Z. & Fesenmaier, D. R., 2016. Smartphone use in everyday life and travel. Journal of Travel Research, Volume 55 (1), pp. 52-63.

- Xiang, Z., 2018. From digitization to the age of acceleration: On information technology and tourism. Tourism Management Perspectives, Volume 25, pp. 147-150.