Introduction

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) defined Open Educational Resources (OER) as: learning materials that enable reuse and repurposing by others without permission. This allows better access to high-quality learning materials for all through a virtuous cycle of materials being developed, improved and repurposed over time and for different contexts. At the end of this chapter, the policy-maker should have developed clear conceptions of how OER can be used in the local context and have clarity on the licensing requirements (UNESCO, 2019). Those OER involve learning objects, curricula lessons, scientific or divulgation papers, books, lectures or even games among others. The Open Educational Quality Initiative (OPAL) presented a study which affirmed that: although open educational resources are high on the agenda of social and inclusion policies and supported by many stakeholders of the educational sphere, their use in higher education and adult education has not yet reached the critical threshold which is posing an obstacle to a seamless provision of high quality learning resources and practices for citizens‟ lifelong learning efforts (OPAL, 2011). Therefore, it is essential to encourage projects to help integrate OER into formal curricula at universities. This research had a main goal to develop a blended learning model in the future to boost this kind of learning-teaching processes in the Engineering Faculty at Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (FI-UNAM).

This research is developed with the support of PAPIME-UNAM program and was conceived to analyze education models, and to develop and try a Flipped Classroom in the Engineering Faculty at UNAM. This research involved developing a multimedia interactive OER, programmed in the open source framework H5P.

Methodology

The applied methodology is the Research-Action Theoretical framework. It is an interactive approach to inquire about and propose solutions to social problems, applied into education classrooms. The Research-Action method emerged in the fifties and it consists of a group discussion and a reflection about the community facing problems. According to Lewin (1946), it is an inquiry common process to find solutions for common troubles. In his revision of state of the art, Colmenares (2003) concluded that: the methodology has evolved, especially in the study of educational reality, and have become a qualitative analysis option.

Research-Action Method was used to analyze the Learning-Teaching Process imparted in the Quality Course at FI-UNAM. To analyze it, an Open Educational Resource (OER) was developed to be used to study theoretic concepts and exercises. Then, some students were asked to study online. After that, they attended an exercises session with a professor. Then, they combined online and presential sessions. At the end, to evaluate the acquired knowledge, a test was applied, and to assess the experience, students were asked to fill in a survey; collecting suggestions and opinions of the participants.

During two academic semesters, students participated in the Blended Learning Session about Acceptance Sampling for Quality. After the two experiences, the reviews and modifications to enhance the model and OER were effectuated.

The academic content elaborated in multimedia format for Quality OER, was provided by professor Octavio Estrada, a participant in this research with more than 25 years in charge of Quality classes for Engineering Students. During that time, he has developed didactic materials to read, exercise and communicate. For this project, two topics were chosen: Acceptation Sampling and Quality Assurance Systems, both subjects were adapted into multimedia format that accomplishes learning objectives from the official curricula program of FI-UNAM (2016).

The Open Educational Resource for Quality was programmed, creating interactive and multimedia materials for students that involve theory, examples and exercises. The Quality OER is compatible with Moodle, because it is the official platform at UNAM. After a programming software analysis, it was programmed in H5P (2018), a framework of open and free code.

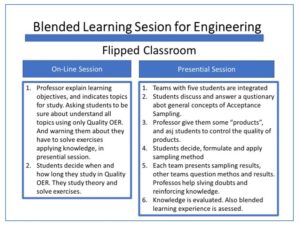

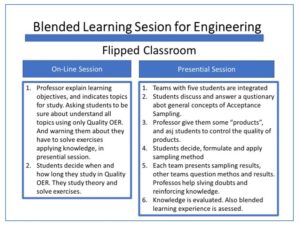

On the other hand, a Flipped Classroom session was designed. The concept is defined by Santiago and Diez (2015) as: a pedagogic model to transfer some learning tasks outside of classroom and use the liberated time and his own experiences to facilitate and potentiate another acquiring processes and practices of how to apply the knowledge. The main goal of the Flipped Classroom is understood for Canarias Government Education Counselors (2016) as: To enhance the teaching-learning process making which is divided into: simple learning tasks (observation, memorizing, resume, among others) outside the classroom, and complex learning tasks (reasoning, examining, argumentation, etc.) inside the classroom, that requires interaction among pairs and help from the professor as a facilitator. The model used two semesters (2019-I y 2019-II), with the participation of attending students in each period independently.

In each semester, each group was selected by an aleatory procedure to compose two subgroups. The first subgroup was part of a face-to-face session; while the other subgroup studied online first, then face-to face later. The participants’ profiles were:

- Bachelor students who are actually attending a Quality course from Industrial Engineering Curricula at UNAM.

- To divide each group, the numbers of the students were selected based on their order in the list: even numbers were assigned to face-to-face sessions, and odd numbers to blending learning sessions.

- As students were part of the same group and the selection was made via an aleatory sample, the composition of both subgroups was similar in profiles.

Quality Topics throughout Blended Learning

In November 2018 (2019-I semester) and March 2019 (2019-II), students enrolled into the Quality engineering course, were invited to participate and evaluate a Blended Learning experience. Students had to use the developed Quality OER and to be in a presential session to study MIL-STD-105E Standard defined by Duncan (1996), for Attributes Sampling and basic concepts about Acceptance Sampling. These topics are part of the required credits of the seventh semester of Industrial Engineering studies at FI-UNAM, and they are curricula topics of Quality.

During the 2019-I semester, 59 students were invited and participated in a Blended Learning session; while, in 2019-II semester, a total of 30 students participated. In both cases, the students were divided into sub-groups.

- Semester 2019-I, subgroup A. Composed by of 30 students (50.85%) that attended a traditional class, where the professor explained basic concepts and solved an example. The subgroup B had 29 students (49.15%) who were part of Blended Learning; beginning with on-line learning throughout Quality OER.

- Semester 2019-II, subgroup A. 15 students (50%) participated in a face-to-face session. While in blended learning, 15 students (50%) were involved. Figure 1 shows the general structure of the model and activities.

Figure1: Diagram of General Structure of Acceptance Sampling Blended Learning.

The composition of the two participant sub-groups is:

- First subgroup (2019-I semester): 25 students (42.4%) used the Quality OER installed in the institutional Platform of UNAM: Moodle (2018). Other four students were never into the platform. One student assigned to a face–to-face session went in the OER. In consequence, a total of 26 students had access into the Quality OER, one of them never uses the OER.

- Second group (2019-II semester). All the invited students were in the platform and participated (15 students).

All the sessions were conducted by professor Estrada, who is in charge of the course and the author of didactic materials. Each group, in their own semester, dedicated one hour and a half to study basic concepts about Acceptation Sampling and the Standard Norma MIL-STD-105E. Group A attended a face-to-face session, while Group B studied the same topics online, throughout Quality OER in Moodle. Both groups solved exercises in this first session. In the second session, all students were present (Group A and group B), the hour and a half were focused to solve new exercises, all about basic concepts studied during the first session. To solve the exercises, working teams were formed, encouraging the interchange of knowledge among students. In necessary cases, the professor explained concepts or procedures to remove doubts.

Results

To analyze the results, all the experiment was divided into three phases: before, during and after sessions. Before, students were invited, had an explanation about their participation tasks and the targets of the research. Each group was divided into two subgroups: one to study in a traditional face-to-face class (A) and the other group studying via blended learning (B). During the teaching-learning process, a face-to-face session was programmed for group A in the university, while, group B had their passwords to study through Quality OER in the moment and place they consider appropriate. In 2019-I, a second session to solve exercises was performed. After both sessions, a presential knowledge test for all the students was applied. Differing from 2019-II, where in the second session, all the students were at the university solving the exercises.

For the second session, all students were organized in teams according to the kind of learning processes, and the main task was to solve some exercises, discussing answers. In 2019-II, there was not a knowledge examination. After all the sessions, Blended Leaning students answered an on-line experiences survey, with the target to know their impressions, suggestions and opinions.

The survey was also applied throughout Moodle; the invitation was made with an e-mail sent to the 25 students attending the Blended Learning sessions in 2019-I and the 15 students in 2019-II. The invitation emphasized the expected contribution from the students. The students had ten days to answer, and a reminder was sent to them one day before the end of the survey. The answers were received anonymously and voluntary. From the 25 students of 2019-I semester, more than half of them (52%) answered the survey; while in 2019-II semester, 73% of the consulted group responded.

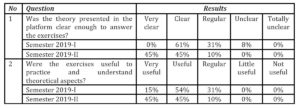

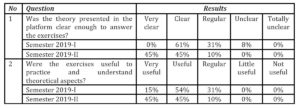

Table 1 shows students’ perceptions about the clarity and usefulness of the contents in Quality OER. All the results of 2019-I surveys were considered to enhance some aspects of Quality OER and Blended Learning model.

Table 1: Clarity and usefulness of theoretical concepts in OER. Students’ answers

The first question inquired if the theory was clear and enough to solve the exercises, 90% affirmed that it was clear or very clear. The second question was about the clarity of OER questions, in this case, almost 70% of the students said that the exercises were clear or very clear, and with modifications in 2019-II, positive answers became 90%.

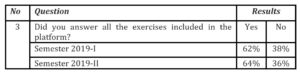

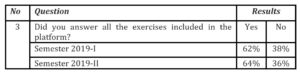

Analyzing the results, in both semesters, more than 60% of the students affirmed that they answered all the exercises of the topic MIL-STD-105E Standard for Attributes Sampling. More than 35% did not answer the question. Comparing between the two semesters, it is evident that the Students’ commitment was higher in the 2019-II group.

Table 2: Exercises in Quality OER, students’ answers

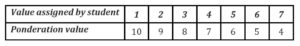

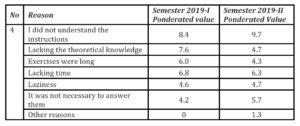

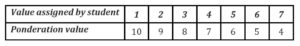

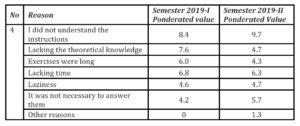

In question number 4, the reasons for not answering all the exercises were inquired. There were six choices and the possibility to add another reason. Each student was able to choose more than one answer, prioritizing them: One for the main reason and seven for the less important reason. During 2019-I, 38% of the students did not answer the question; in 2019-II, 36% were without answers. In this semester, a student did not distinguish the priorities, so his answer was discarded. To calculate the weight of the reasons, a ponderation was used as a scale as shown in table 3.

Table 3: Ponderation reasons

To calculate the weight: the value assigned for the student was multiplied for the correspondent factor as it is shown in Table 3. Then, these values were added and divided by the total number of the obtained answers (respondents). Table 4 shows the results in a scale from 10 to 0, where 10 is the most important reason and zero represents the least important.

Table 4: Reasons to not answer all the questions in OER, students’ answers

The results in table 4 indicate the main reason for not solving all the exercises which was they did not understand the instructions; in consequence, a revision of the instructions is being made. Comparing between the semesters’ values, it detected a general improvement in the other factors. Only one student wrote a different reason: I incorrectly manage my time and I dedicated little time to solve the activities.

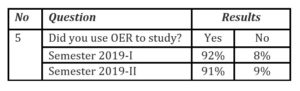

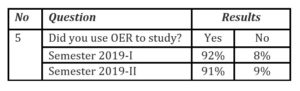

The fifth question had the target to determine if the students really used the Quality OER. In both semesters, students used the OER to study (more than 90%), as shown in table 5.

Table 5: Students use of OER

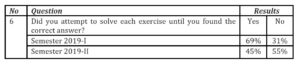

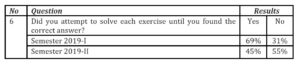

To establish the interest and interaction of the students with Quality OER, question six was included. In table 6, it can be observed that more students in 2019-I tried to solve the exercises until they found the correct answers.

Table 6: Attempts to answer the exercises in Quality OER, students’ answers

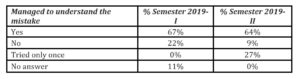

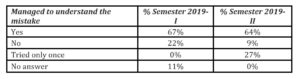

The next question was only for the students that attempted to respond to the exercises more than once; and the question was: Did you manage to understand the mistakes? In table 7, the answers reveal that, in both semesters, more than sixty percent of the students understood the correct answer.

Table 7: Understanding of mistakes while answering the exercises in Quality OER

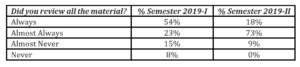

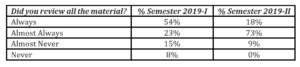

Table 8 shows the answers to the question: Did you check all the slides of Quality OER? Even the exercises’ grades in the last slide? In both groups (2019-I and 2019-II), the participants answered with: always or almost always; however, the platform registers show that nobody answered all the exercises.

Table 8: Reviewing the material on Quality OER, students’ answers

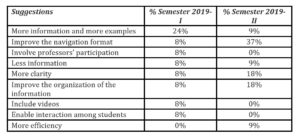

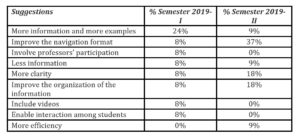

To enhance the Blended Learning Model, the students suggested more information, more examples and better Web navigation features. 46% of the students did not consider it necessary to change anything. All opinions by the groups are shown in Table 9.

Table 9: Improvements suggested by students

77% of the students of 2019-I preferred a combination between face-to-face sessions complemented with on-line studies. In addition, nobody preferred on-line study, while 23% said that they would choose traditional courses with a professor. In 2019-II group, the responses were similar. 81% of the students preferred a blended learning course, while 9% would like to preserve a professor explanation in a face-to-face class.

To end the survey, the students expressed their opinions about Quality OER and Blended Learning without restrictions. Table 10 presents the obtained opinions, in both of the surveyed groups.

Table 10: General comments about Blended Learning experiences, answers from students of 2019-I y 2019-II groups

Analysis and Discussion

A study about Blended Learning use in two engineering students’ groups at UNAM was made. The Blended Learning raised an interest among the students that showed a positive reception towards changing the study models. The Blended Learning model was proved, using Quality OER to study theoretical concepts online about Acceptance Sampling, and complimented with exercises sessions with professors. At the end, a reflection of the students’ experiences was obtained. In general terms, both groups’ answers were similar. From the students’ reflections, it can be perceived that participating in a Blended learning session encouraged them to search and use more available on-line materials, as a complementary tool of learning. About the professors’ role in classes, the students expressed that professors act as transmitters of knowledge. It is through his/her experience about how to apply knowledge in real situations and how to avoid obstacles that can be found, they offer possible solutions to face problematic situations. All these factors are usually less described in texts and study materials. Most of the students concluded that it is recommendable to use Blended Learning Systems. All the comments and suggestions have been considered to improve Quality OER and Blended Learning Model.

Conclusions

The Blended Learning Model Test was successfully applied. It was formulated for Acceptance Sampling theme. The involved topics are part of the seventh semester of bachelor Industrial Engineering studies at the Engineering Faculty of UNAM. Students from two semesters were invited: 2019-I and 2019-II; all the participants were enrolled in curricula courses. For the Blended Learning sessions, an OER about how to use the MIL-STD-105E Standard for Attributes Sampling was designed, programmed and utilized. Students groups were composed of 59 students and 24 students respectively. For each semester, the group was divided into two subgroups: First group, 30 students (50.85%) attended a traditional lesson, while 29 (49.15%) studied topics through OER, developed with educational readings and writings from the same professor. A knowledge test was also considered; however, it was not possible to apply it in both semesters, in consequence, the results are not presented.

A Blended Learning Model Pilot Test was useful to detect and adjust some aspects of the OER, for instance: make shorter exercises and add some Web navigation instructions. The class seems to be a good experience for students, because they have the opportunity to study theoretical aspects at their own rhythm, however, some potential areas concerning the OER and Blended Learning sessions were detected to enhance in the future.

In conclusion, lecture readings and writings were integrated in an interactive OER, involving theoretical and practical aspects to learn about Acceptance Sampling. A face-to-face explanation about how to solve an example with a professor answering, questions was performed. Both, OER plus face-to-face sessions constitute the first Blended Learning Model in Acceptance Sampling topics at FI-UNAM. The participants stated that they are interested in participating in Blended Learning Modality of learning, because they considered it a good way to study by themselves, reinforcing learning with a professor. The objective is to complement the obtained results with the new experiences of Blended Learning. In consequence, in the future, the Blended Learning Model would be enhanced for university students of Mexico.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by UNAM-DGAPA-PAPIME with project: PE311218.

References

- Tamara Alcántara-Concepción, Victor Lomas-Barrie, Octavio Estrada-Castillo and Aline Lozano-Moctezuma (2019). . Modelo de aula invertida: prueba piloto en la Facultad de Ingeniería de la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. ALTEC 2019 Medellín, realizado: del 30 de octubre al 1 de noviembre de 2019, en la Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana.

- Alcántara-Concepción, T. (2017), ‘University Participatory Experience building Open Education Resources’, Journal of e-Learning and Higher Education, 2018 (14).

- Area, M., Adell, J. (2009), ‘e-Learning: Enseñar y aprender en espacios virtuales’, en J. De Pablos (Coord), Tecnología Educativa, pp. 391-424, Aljibe, Málaga, España.

- Brown, J. (2011), ‘Likert items and scales of measurement?’, SHIKEN: JALT Testing & Evaluation SIG Newsletter, 15 (1), 10-14.

- Colmenares, A. (2011), ‘Investigación-acción participativa: una metodología integradora del conocimiento y la acción’, Voces y Silencios: Revista Latinoamericana de Educación, 3 (1), 102-115, ISSN: 2215-8421.

- Consejería de Educación y Universidades del Gobierno de Canarias (2016), ‘Aprendizaje invertido (Flipped classroom)’ [en línea], [retrieved: junio de 2019], http://www3.gobiernodecanarias.org/medusa/ecoescuela/pedagotic/aprendizaje-invertido-flipped-classroom/

- Duncan, A. (1996), Control de Calidad y Estadística Industrial, Alfaomega, México.

- FI-UNAM (2016), ‘Ingeniería Industrial. Mapa curricular 2016’ [en línea], [retrieved: febrero de 2018],http://www.ingenieria.unam.mx/programas_academicos/licenciatura/industrial_plan2016.php

- Glasserman, L., Rubio, M. y Ramírez, M. (2014), ‘Recursos Educativos Abiertos en la práctica docente’ [en línea], en T. d. Monterrey (Ed.), Metodología y estrategias de enseñanza, pp. 46-64, [retrieved: septiembre de 2018], http://catedra.ruv.itesm.mx/handle/987654321/833H5P (2018), ‘H5P’ [en línea], [retrieved: abril de 2018], https://h5p.org/

- Lewin, K. (1946), ‘Action research and minority problems’, Journal of Social Issues, 2 (4), 34-46.

- López, L. (2017), ‘Elementos básicos del trabajo en equipo. Curso: Trabajo en Equipo – Nivel 1’ [en línea], Centro Virtual de Aprendizaje del Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Monterrey, [retrieved: abril de 2018], http://www.centroscomunitariosdeaprendizaje.org.mx/

- Moodle (2018), Moodle (version 3.4.3) [software], Dougiamas, M., [retrieved: April 2018], https://download.moodle.org/

- Moodle-H5P (2018), H5P Plugin for Moodle (version 1.7) [software], Joubel AS, [retrieved: mayo de 2018], https://moodle.org/plugins/mod_hvp

- Mortera, F. (2010), ‘Implementación de Recursos Educativos Abiertos (REA) a través del portal TEMOA (Knowledge Hub) del Tecnológico de Monterrey, México’, Formación Universitaria, 3 (5), 9-20.

- OECD (2007), ‘Giving knowledge for free – the emergence of Open Educational Resources’, IMHE INFO, Julio 2007, pp. 1-4, [retrieved: June 2019], http://www.oecd.org/education/imhe/38947231.pdf

- OECD (2017), El conocimiento libre y los recursos educativos abiertos [en línea], Centro de Nuevas Iniciativas (Coord), Junta de Extremadura (Ed), [retrieved: junio de 2019], https://www.oecd.org/spain/42281358.pdf, ISBN: 978-84-691-8082-2.

- OPAL (2011). Beyond OERShifting Focus to Open Educational Practices. OPAL Report 2011. [retrieved: September 2018], https://www.oerknowledgecloud.org/archive/OPAL2011.pdf

- Rodríguez, N. (2011), ‘Diseños Experimentales en Educación’, Revista de Pedagogía, XXXII (91), 147-158, [retrieved: 25 septembre 2018], http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=65926549009, ISSN: 0798-9792.

- Trillo, P. (2012), ‘Recursos Educativos en Abierto: evolución y modelos’, Foro de Educación, 10 (14), 191-205.

- UNAM (2018), ‘Tu aula virtual’ [Moodle], [retrieved: noviembre de 2018], https://tuaulavirtual.educatic.unam.mx/UNESCO (1989), ‘Material didáctico escrito: Un apoyo indispensable’ [En línea], UNESCO-FNUAP, [retrieved: junio de 2019], http://biblioteca.udgvirtual.udg.mx/jspui/bitstream/123456789/1939/1/Material%20didáctico%20escrito%20un%20apoyo%20indispensable.pdf

- UNESCO (2008), Etapas hacia las sociedades del conocimiento: material de referencia para comunicadores, IPS América Latina, Montevideo, Uruguay, ISBN: 978-92-90-89-121-5

- UNESCO (2019), Guidelines on the development of open educational resources policies [Online], UNESCO and Commonwealth of Learning, France, ISBN: 978-92-3-100341-7, [retrieved: September 2018], https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000371129

- Vilchis, N. (2016), ‘Recursos Educativos Abiertos, Reseña del libro Recursos Educativos Abiertos, un medio de innovación para la educación a distancia’, Revista Mexicana de Bachillerato a Distancia, 8 (16), 156-158.