Introduction

Taekwondo is a Korean martial art that has gone through many transformations. While the origins of Taekwondo can be traced back to over 2000 years, Taekwondo was developed formally into a martial art during the late 1940s and 1950s, where in 1959 the first Taekwondo governing body, the Korean Taekwondo Association (KTA), was formed (Madis, 2003). Following, in 1966, the International Taekwondo Federation (ITF) was formed, and primarily due to political reasons, a separate body, the World Taekwondo Federation (WTF) was established in 1973 (IOC, 2019; Kang and Lee 1999; Southwick, 1998). The WTF rebadged itself to World Taekwondo (WT) in 2017.

The functions of both the ITF and WT include various competitions on differing aspects of the martial art, education, establishment and maintenance of standards in the martial art and collaborating with affiliated member organizations and relevant sporting organizations, such as the International Olympic Committee, etc.

While the martial art of Taekwondo with its broad range of skills and techniques continues, sports Taekwondo has evolved into a multi-million-dollar global sport, where practitioners hone on a limited, but specific set of Taekwondo skills for competition.

The WT comprises of five continental union governing bodies. World Taekwondo Oceania, World Taekwondo Asia, World Taekwondo Africa, World Taekwondo Europe and World Taekwondo America. The WT, in total, currently comprises of 206 member countries and an excess of 70 million practitioners in the sport.

World Taekwondo held its first World Championships in Seoul, Korea in 1973, and the sport has been contested every two years since. At the first World Championships, the sport was contested by 19 nations over three days. At the last World Championships in 2017, the sport was contested by 183 nations plus 1 refugee team with a total of 945 athletes participating in the world championships conducted over a seven-day period (WTF, 2017).

Since being recognized by the International Olympic Committee in 1980 followed by its appearances at the Seoul Olympics in 1988 and Barcelona Olympics in 1992, (IOC, 2019) the sport of Taekwondo continues to evolve, such that the sport of today is quite different to that of its first Olympic appearance.

The sport became a full medal sport in the Olympics in 2000 at the Sydney Olympic Games, and has continually undergone dramatic changes to ensure safety of the athletes, and transparency and fairness in decision making through the applications of technologies – both in the athlete’s competition equipment as well as decision making technologies for the referees (Leveaux, 2012).

The international competition rules were first enacted in May 1973 and had been amended on twelve (12) occasions to February 2009 – a period of nearly 36 years. However, in the nine-year period from March 2010 to May 2019, the competition rules have been amended no less than thirteen (13) times; and during this period on four occasions the rules have changed twice in the same year (WTF, 2019). This excludes the continual variations to the interpretations and applications of the rules as well as the processes surrounding general competition, such as match management by the referees and coaches.

The sport is participated throughout the Oceania region, with 19 member countries participating in the Olympic Games, World Championships, Pacific Games and Oceania Championships. At the recent 2016 Rio Olympics, the region was represented with a full quota of athletes made up of 4 athletes from Australia, 1 from New Zealand, 2 from Papua New Guinea and 1 from Tonga. (WTF, 2016) As the sport of Taekwondo is changing dynamically, with the interpretations of competition rules varying from one major event to another, it is becoming increasingly difficult for stakeholders in the sport to keep abreast of these changes, and in the applications of these changes in competition and their implication in competition preparation.

This paper reports on an examination of the existing educational offerings and educationally related issues in the sport for both coaches and referees, with focus on the Oceania region. Through a series of interviews with relevant stakeholders in the sport, this work looks at the current and differing educational programs being conducted nationally and internationally, and presents a pathway to progress in the enhancement of educational offerings primarily within the Oceania region and subsequently improve the educational standards of the sports practitioners.

Literature Review

A key in enabling professionals to become highly effective is in the taking of professional learning opportunities (Pittaway, 2012). While this is aimed at the workplace, it would equally apply to coaches and referees in the sporting area, especially at the elite and professional levels. The “provision of practice based (e.g., workplace) experiences is now almost a universal requirement for students” to ensure the acquisition of the relevant skills on completion of a course (Higgs et al, 2012, p 101) The involvement in activities that maximize learning allows participants to grasp not only intended outcomes but also the underlying context on which the activity was based. Learning then becomes an experience and provides participants with the knowledge to perform effectively. By having participants actively involved in the learning process increases what is remembered, how well it is assimilated and how it is applied to the new situations (Maznevski, 1996). Active involvement in learning increases what is remembered, how well it is assimilated by the student and how it is applied to new situations. This is, in part, because the participants need to think about what they are doing.

Context is important in learning, and the concept of situated learning (Lave, 1996) is a key element in engaging course participants. To maximize the quality of participants’ learning outcomes, learning environments should be constructed to ensure participants are exposed to different situations and / or contexts. Through aligning learning outcomes and possible assessment tasks, it is possible to provide participants with the opportunity to demonstrate a deeper engagement with their learning in a variety of situations (Meyers & Nulty, 2009).

‘High quality’ learning outcomes result from the interplay between the learning efforts of the participants and the methods employed in the delivery (Meyers & Nulty, 2009). When participants engage with the context associated with the subject matter to be delivered, they are more likely to achieve better outcomes, keep their attention levels high and improve their understanding of the content delivered. Engaging participants in the learning process is particularly relevant when subject content is authentic and aligned to situations participants may encounter in their involvement and role(s) in the sport.

To effectively educate participants, research suggests the educational style and content must be adapted to participants of various ages, various levels of experience and potentially in some cases to address differing cultures. As such, the learning requires to accommodate the varying participant cohort. In many educational sectors, this has led to a more interactive, experiential learning approach across a wide range of disciplines such as medicine, education, business and management. For example, as improvements to higher education continue and the effectiveness experiential learning becomes more evident so does the need for innovative ways to incorporate this ‘experience’ into the classroom (Boggs et al 2007).

Effective learning requires participants to be actively involved with the learning experience and then have time to reflect on that experience. Active or experiential learning is one approach to engage participants in the learning experience and is gaining prominence through increased adoption in the classroom (Sojka & Fish, 2008). Active or experiential learning involves all participants and the learning activity corresponds in some way to the world outside the classroom. As experience suggests “not all problems have single, correct answers” (Eisner, 1992 p75-76 cited in Boggs et al, 2007) and as such the learner has control over their own learning experience.

Two well-known techniques – role play and simulation – are well suited to the active or experiential learning paradigm. A role play focuses on unstructured situations where participants improvise their role within a given boundary. In contrast, simulations are defined more precisely than role plays and include guiding principles and specific rules. However, both techniques require extensive preparation and development to ensure suitable participant learning outcomes. Both role play and simulation enable participants to put themselves in situations they have never experienced (Joyner & Young, 2006) and assist participants to see multiple perspectives of the same problem or the different issues confronting the same problem as both techniques focus on learning by doing (Doorn and Kroesen, 2013). Hence, these techniques are deemed very effective in promoting participant competencies as they provide the opportunity for rapid and timely feedback to reinforce understanding for both role players and observers (Joyner & Young, 2006).

Effective role plays and simulations can stimulate participant interest in content areas and also enable the consolidation of previous learning through ‘practical application’ of knowledge gained (De Neve & Heppner, 1997). As such, they can be thought of as ‘a continuous, interactive, dynamic teaching approach [to engage] participants in meaningful learning’ (Joyner & Young, 2006 p 229). The collaboration that takes place within an active or experiential learning environment is of benefit to all participants. For example, less experienced participants benefit from the expertise of fellow participants, while those participants who possess expertise in the area will strengthen their knowledge and skills through sharing that expertise (Murphy & Gazi, 2001).

A key element in the learning outcomes from both role play and simulation is that of reflection; where ‘reflection-on-action’ or ‘retrospective thinking’ is seen as a means of consolidating learning outcomes (Nestel & Tierne, 2007). This reflection is twofold as learners reflect ‘in’ (those with parts in the role play or simulation) and ‘on’ (those who are observers).

Research Methodology

The research methodology followed an interpretive case study approach using a phenomenological methodology to gain internal (organization) and external (course participants) perspectives of the educational program needs of the organization, and participants in the sport within the Oceania region. Phenomenological interviews were used so as to capture privileged knowledge of those who are or were involved with this research issue in relation to their differing cultures, history and experiences. The goal, by using phenomenological interviews, was to analyze, address experiential gaps, and make precise meanings of those experiences for the development of a suitable model or framework for the delivery of sports taekwondo education in the Oceania region.

A case study is an investigation of a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context providing rich contextual data obtained from an organizational setting. A single case study has the ability to increase our understanding of a particular situation (Yin, 2003). It has been argued that a single case study, while not generalizable, has the ability to provide a valuable insight into a known context (Duhan et al, 2001) and that the findings may be appropriate for someone in similar circumstances (Cousin, 2005).

Interviews

Interviews were used to provide the opportunity to draw on both the past and the present so as to extract a deeper understanding of issues compared to a simple survey type enquiry (McCracken, 1998). The use of interviews provides the investigator with the avenue to ask respondents for facts as well as gathering opinions (Earlandson, 1993).

All the participants were or had been involved in the sport in either a coaching and / or refereeing at a senior level – national through World Championship level, and the majority had been involved with the sport for more than fifteen years.

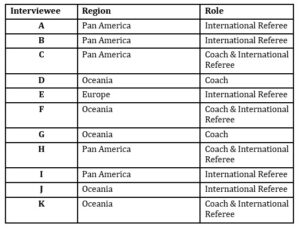

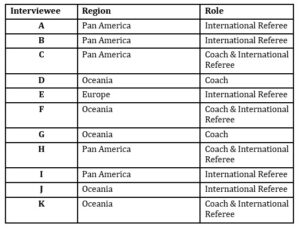

Chain sampling was used to solicit participants who are “information-rich” as Patton (1990) indicated are good examples and good interview subjects. The 11 participants (See table 1) were chosen based on the individual’s availability, and experience in the sport. This technique of purposeful sampling was employed due to the concerns in the study to maximize discovery of the problem and the heterogeneous patterns occurring with the framework of the study (Erlandson, 1993).

Table 1: Interviewees and Region

The interviews were of a semi-structured format using probing style questions. All 11 interviews were recorded using a voice recorder and then transcribed. Additional field notes were taken on the time of each interview. The majority of the interviews were of 30 to 45 minutes duration, with the one of approximately 20 minutes.

All participants in the study participated voluntarily and were informed, if they wished to do so, they were able to withdraw from the study without the need to provide reason or justification.

The project was assessed by the University of Technology Sydney Ethics committee as not being high risk and UTS ethics approval (UTS HREC ETH17-1287) was granted on 1 May 2017.

Each interview commenced with the following open question: “In relation to your Taekwondo referee (or coach) education, what is the most memorable experience you have had?”; this was then followed by further probing questions. The questions focused on experienced phenomena, and were concerned with drawing out each person’s subjective interpretation of their experiences in the sport and their recollections. The questions were open, empathetic and not leading, with the focus on encouraging the participant to explore his or her experience(s) and interpretations of the many potentially differing aspects of the phenomenon. Questions implying any expectation or considered to be leading were avoided, as Goulding (2005) suggests it is necessary that the subject’s responses and reflections are not influenced, swayed or led by the interviewer’s style. The interviews additionally explored cultural and relationship issues to provide rich, significant experiential material.

As the participants came from differing countries and cultures, it was important to conduct interviews in environments suitable to the participant. All interviews were at relevant locations to suit the interviewees at the time, e.g., attending a World Championship or other international event, with as little intrusion and disruption to the participants as possible. All participants already had considerable exposure to and been accustomed to the environments where the research was being conducted and was not foreign to them. Due to the nature of the sport and the individual’s level of participation in the sport, they were very familiar with communicating with and talking to people from other countries and cultures; and through their involvement in the sport, they could be considered as “global citizens in the sport”.

No individually identifiable data were required for this work and as such all interviews were de-identified and the transcripts sanitized to remove trace(s) of personal or organizational elements ensuring that there is no tracing back to single contributions, or identification to any of the participants. Only general themes were identified. The collected date were only used by the researcher and were not given to the organization(s).

There exists a variety of qualitative data analysis methods including content analysis, constant comparison and pattern matching. It is the intention to ensure the data collection and analysis of the data is explicit to “encourage theory development or progress current knowledge and understanding” (Shaw, 1999), and through the data analysis interpret the phenomena in the terms the interviewee places on them (Creswell & Creswell, 2017). Using an interpretivist approach, data were analyzed so as to provide a deep understanding of issues relevant to the sport’s education in the region. Emerging conclusions made from the study provided a sound understanding of the research situation and provided a grounded basis for developing theories and framework for the delivery of the education process.

Findings and Results

There were considerable references to the differences in the educational materials provided and, in the medium(s), depth in the explanation of rule interpretations, duration and extent of education sessions. This subsequently creates levels inconsistencies in rule interpretations and their application. Athletes, coaches and referees were found to have differing understandings of the application of any particular rule at a given time, and in some cases, this variation in the rule interpretation would be from one event to another, or even between referees and coaches at the same event.

While coaches and referees generally had sound, basic understandings of the actual competition rules, the real problem area lays in the deeper understandings of the competition rules, the interpretation and the application of that interpretation in a given competition. Problems were identified to stem from variations in an interpretation for a particular event, and this information not being disseminated to coaches and referees for subsequent events. In situations where a new interpretation was being made of a rule, only those attending that particular event would be aware of the new interpretation and how it was being applied. The dissemination of a new interpretation to other stakeholders is totally reliant on those who attend the event to ideally distribute the changes or updates, as no official correspondence comes from the world body.

Within the Oceania Region this is even more problematic due to the fact that not all stakeholders have access to major events due to financial constraints (personal, national and regional), various cultural issues (e.g., language, religious, educational, etc) and time commitment. In addition, many of the national bodies within the region do not have suitably experienced educators in the sport and are reliant on the regional governing body to fill in this shortfall.

Global Education Avenues – Referee and Coach Seminars

Education in the sport for coaches and referees generally falls under two categories. These being formal seminars conducted by the world governing body, the regional bodies and in some cases the relevant national body, and pre-event event training seminars for those referees who are officiating at that event and in separate coaching debriefs held immediately prior to a particular event.

Currently there is no formal requirement or syllabus provided by the world governing body to regional bodies or national associations for their referee and coach education. In general, each region, and in some cases a national body, is providing its own independently developed educational program.. As such, there exists multiple education programs with different structures and different levels of content in relation to the interpretations and with the competition rules.

It is not uncommon that at any one time there are differing interpretations ofthe same rule being delivered in educational programs across differing cohorts. Content for the regional and national programs is not provided by the world governing body. Regional and national bodies develop their own educational programs by sourcing content through interested individuals within their organization who attend international events and/or international training programs run by the world body and then pass on this information onto their regional and/or national body.

Global Education Avenues – Pre-Competition

Prior to all competitions at the international and regional levels, a referee meeting and a coach/manager debrief are conducted. The latter are often referred to as the Head of Teams Meeting.

The referee meetings, while addressing logistical issues and event management relating to the referees, also double up for pre-event education or refreshing of rules and interpretations to be applied at that particular event.

The Head of Teams meetings address matters related to the competition draw, competition logistics from the coach and athlete perspective; and provide a debrief of the rules and interpretation for the event. This is normally conducted by the referee chairperson for that event.

There is no formal pre-event education information relating toto rule interpretation for a specific competition, provided to either the coaches or referees prior to the event. Information related to rules and their interpretations are only provided at the respective Head of Team or Referee meeting immediately prior to the competition.

Global Referee and Coach Education – Competition Onsite

Educational seminars for coaches and referees vary from event to event at the international level.

Head of Team Meetings – Coaches

The Head of Teams meetings are usually attended by the Head of Team and one of the team’s coaches for each team at that competition. The Head of Teams meetings at World Championship and regional level are quite detailed and may run up to several hours. At other international events, such as Open championships, they usually run for around an hour plus, with regional championship Head of Team meetings running for an hour or two. However, at all international events sanctioned by the World Taekwondo, coaches are required to hold a current regional coach license to have access to the competition area. This accreditation is usually conducted as part of the region’s formal referee and coach education programs. At some open events the respective regional body may also run coaching license/accreditation courses which are run usually over a three-or-four-hour period. These courses are an abridged version of the formal coaching course specifically designed to enable coaches to gain their coaching license accreditation for the event.

In general, all of these follow a similar format where content is presented either as simply as a verbal presentation or verbally and supported with a PowerPoint presentation, with both providing Q and A.

Referees

The structure of the pre-event referee meeting varies from an hour briefing for an open event up to a compulsory 3-day training program prior to a major event such as World Championships or Grand Prix, etc.

At these major events and at some, but few, Open events the referee education program consists of verbal presentation supported with PowerPoint presentation, familiarization with the competition equipment, and match practice, where the referee practices hand signals and match management with simulated matches.

Generally, at Open events the Referee meetings are quite brief and consist of addressing logistical matters and a debrief over the rules and interpretations. On some occasions this is presented via PowerPoint and followed by some discussion.

Oceania Region Referee and Coach Seminars Structure

The Oceania region differs somewhat from the other regions and the world body offerings in so much that the education program for coaches and referees is conducted in one seminar to both cohorts, and offers regional accreditation for coaches and referees at the same seminar.

Coaches and Referee Seminars

The Oceania region governing body for the sport provides a standard education package for all member countries in the region. This package is designed such that coaches and referees attend the same program to ensure both groups of stakeholders are receiving the same content, whereas with some of the other regions’ coach and referee, education is conducted separately. The program is delivered by presenters certified by the World Taekwondo Oceania (WTO – regional governing body). Currently there are five presenters in the region – three in Australia, one in New Zealand and one in New Caledonia.

A member country, state or province, or a club in a member country may request for a seminar to be conducted. Once approved by the WTO, a presenter will be appointed to deliver the standard package for coaches and referees to ensure consistency of education across the region. However, issues arise due to the availability of local funding to hold seminars, availability of presenters; and there is no obligation by a country to use the regional body’s educational program. Additionally, some of the member countries in WTO have been elected to deliver their own educational program. The only commitment to using the regional program is when a coach is seeking the necessary accreditation to officiate at an event sanctioned by the world and / or regional body.

Oceania Education – Pre-Competition

At most, if not all domestic, national or regional events in the region, there is no pre-event dissemination of updated rule interpretations. Within the 19 member countries, only Australia, New Zealand and New Caledonia have international qualified referees (IR) which further limits the likelihood of stakeholders being up to date. The access to current rule interpretations is further impacted by the region’s IRs only coming from three countries and appointments to international competition are usually made by the world body without input from either the regional body or the national body, thus there is no guarantee that each of the three countries is represented at each international event. With any event, sanctioned by the world body, only international referees licensed by the world body may be appointed to officiate, and national referees cannot officiate. This limits the opportunity for national referees to gain match-time experience and attend the pre-competition referee training.

Oceania Education – Competition Onsite

The referee training and coach debrief for an event at the regional level usually consists of a joint meeting, held for approximately one hour, where at the Head of Team meeting, both referees and team officials meet for a debrief of the competition logistics and application of rule interpretations for the event. This meeting is chaired by the Competition Manager, for the matters related to the running of the competition, and the Referee Chairperson for the event, who would cover matters related to rules and their application. Due to the nature of the region, certain concessions need to be made to accommodate coaches and players while still maintaining compliance to the world body’s competition rules and regulations.

The referee would follow on from the Head of Teams meeting with a more specific session with a more in-depth discussion on rule interpretations and their applications and, at some events, a familiarisation with the competition’s electronic scoring and video review systems. These sessions are usually run over a one-to-two-hour period.

Discussion

Changes are not being disseminated to either regional or national bodies by the world governing body (WT). To acquire current information necessitates a country to either have its international referees attend a five-day education seminar, usually requiring international travel or in the hope they be appointed by the world body to officiate at a major world event and attend the event and the pre-event training. The travel and course costs, which are usually in the vicinity of three to four thousand dollars, are often borne by the individual. There is no funding from the world body and the regional and many of the national federations do not have the financial resources to support the travel. It is then necessary for this information to be disseminated to the local referee and coaching corps via some domestic process, which in most cases does not occur.

This form of unstructured information dissemination, due to the lack of processes and time, often leads to the relevant stakeholders at the domestic, national and in some cases regional levels having differing levels of currency with interpretations, understandings and applications of competition rules and regulations. This irregularity impacts not only on the competition(s), but also has considerable bearing on the game management and training of the athlete in competition and those officiating in competition.

Educational courses for referees and coaches, in general, are run infrequently. In some countries, courses may only be offered once a year, and even less with the smaller countries in the region. Due to the earlier mentioned rate of changes in competition rules and interpretations, this infrequency and lack of ability to gain up-to-date information critically disadvantages the greater majority of countries in the Oceania region.

Currently, educational programs for referees and coaches, conducted by the world and regional bodies, are delivered in a traditional classroom format employing everyday educational tools, e.g., PowerPoint presentations. The hosting by a regional or national body of an international referee course, delivered by the world body, will incur costs of upwards of twenty to thirty thousand dollars with little or no financial return to the host organization.

In additn to the delivery of course content, the coach and referee accreditation assessment processes in the regional and global offerings take little advantage, if any, of modern technologies and, with the exception of pass or fail result, do not provide any formative feedback for the individual participants. In addition to the lack of feedback, the processing of the results may take upwards of several months for the candidate to receive results. In some cases, the results are not distributed to the candidates but rather to the respective national body.

This work examines the gap in the current provision of educational offerings for Taekwondo coaches and referees in the Oceania Region. The findings highlighted three key focal areas which were found wanting in the region: Availability of skilled educators;

- Access to suitable educational programs; and

- Access to current interpretations and application of the sport’s rules and regulations.

In addition to the above, three additional factors impact on the current environment:

- Differing cultural issues within the region;

- Lack of available financial resources; and

- Organizational and infrastructure issues within the region.

The Oceania region differs considerably from the other four global regions in the sport (PanAmerican, European, African and Asian regions), which, due to differing but unique factors, significantly impacts the area of referee and coach education in the region. These factors include differing socioeconomic environments in and between the region’s countries, accessibility to technologies, cultures including religious beliefs and differing languages and dialects, educational standards, and available disposable income costs. This work will assist in the development of the sport’s educational programs to provide a more innovative program delivery, subsequently leading to an increase in the standards of officiating and coaching, and increased participation in officiating and coaching in the sport in Oceania.

Conclusion and Future Research

The role of education in the sport of Taekwondo in the Oceania Region is a complex problem. The Oceania region consists of 19 member countries with differing languages, educational backgrounds and standards, available technologies, financial access – organizationally (both with the regional body and individual country’s associations) and individually with participants. Additionally, the sport is continuing to undergo considerable changes, such that, rule modifications, interpretations and applications are being made on a frequent basis. To ensure that the sport continues to be contested at the highest levels, it is imperative that a suitable and current educational program be available to all participants in the sport.

An understanding of the issues related to the delivery of the sports education in the Oceania region is a key to enable the development of a framework for the management and delivery of an educational program using the principles of blended learning within a region of differing cultures and socioeconomic environments.

This work lays the platform for the development of an educational model based on the principles of eLearning and Blended Learning to address the needs of the sport in the Oceania Region. Such a model would be a component of a more complete educational framework which would also be expected to not only provide an educational program and structure, but also address the management of the sport’s educational program taking into consideration the various cultural issues and challenges the region provides.

While the benefits of an educational program designed using the concepts of eLearning and blended learning are apparent, the challenge is to ensure all stakeholders within the region see and accept the value and benefits of the program, and subsequently adopt the program. It appears, through the author’s earlier work, that this may be possible with the improvement of educational methods and training for end users. Such an educational program needs to be accessible across the regions.

The significance of this work is in the examination of the educational needs for taekwondo coaches, referees and other competition stakeholders within the Oceania region. Depending upon the success and uptake of the model, the model could then be applied to other sports within the region and used in other regional Taekwondo sports education programs for referees and coaches, and potentially for adoption by the world governing body – World Taekwondo.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

References

- Boggs, J.C., Mickel, A.E. & Holtom, B.C. (2007) Experiential Learning Through Interactive Drama: An Alternative to Participant Role Plays, Journal of Management Education, (31, 6), pp832-858

- Cousin, G. (2005). Case study research. Journal of geography in higher education, 29(3), 421-427.

- Creswell, J.W. and Creswell, J.D., (2017) Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage publications.

- DeNeve, K.M. & Heppner, M.J. (1997) Role Play Simulations: The Assessment of an Active Learning Technique and Comparisons with Traditional Lectures, Innovative Higher Education, (21, 3), pp231-246

- Doorn, N. & Kroesen, J.O. (2013) Using and Developing Role Plays in Teaching Aimed at Preparing for Social Responsibility, Science and Engineering Ethics, (19), pp1513–1527

- Duhan, S., Levy, M. and Powell, P. (2001) Information systems strategies in knowledged-based SMEs: the role of core competencies, European Journal of Information Systems, 10(1), pp 25-40.

- Erlandson, D.A, (1993), Doing a Naturalistic Inquiry: A Guide to Methods, Newbury Park, CA.

- Goulding, C., (2005) Grounded theory, ethnography and phenomenology: A comparative analysis of three qualitative strategies for marketing research. European journal of Marketing, 39(3/4), pp.294-308.

- Higgs, J., Barnett, R., Billett, S., Hutchings,M., Trede, F., (Eds) (2012) Practice-Based Education Perspectives and Strategies Rotterdam, The Netherlands Sense Publishing.

- (2019) [Retrieved June 16, 2019], https://www.olympic.org/taekwondo

- Joyner, B., & Young, L. (2006). Teaching medical students using role play: twelve tips for successful role plays. Medical teacher, 28(3), 225-229

- Kang, W.S. & Lee, K.M., (1999) Taegwondo hyeondaesa. Seoul:Bogyeong Munhwasa

- Lave, J. (1996) Teaching, as Learning, in Practice, Mind, Culture and Activity, 3, pp. 149-164.

- Leveaux, R. (2012). 2012 Olympic Games Decision Making Technologies for Taekwondo Competition. Communications of the IBIMA, 2012, 1.

- Madis, E. (2003). The evolution of taekwondo from Japanese karate. Martial arts in the modern world, pp 185-209.

- Maznevski, M.L. (1996) Grading Class Participation, Teaching Concerns, January, pp. 1-3.

- McCraken, G., (1988), The Long Interview, Newbury Park, CA, 1988

- Meyers, N.M. & Nulty, D.D. (2009) How to use (five) curriculum design principles to align authentic learning environments, assessment, participants’ approaches to thinking and learning outcomes, Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 34(5), pp. 565-577,

- Murphy, K.L & Gazi, Y. (2001) Role Plays, Panel Discussions and Simulations: Project-Based Learning in a Web-Based Course, Educational Media International, (38, 4), pp261-270

- Nestel, D. & Tierne, T. (2007) Role-play for medical participants learning about communication: Guidelines for maximising benefits, BMC Medical Education, (7, 3)

- Patton, M. (1990) Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods (2nd ed.). Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

- Pittaway, S.M. (2012) Participant and Staff engagement: Developing and Engagement Framework in a Faculty of Education. Australian Journal of Teaching Education, 37(4)

- Shaw, E., (1999) A guide to the qualitative research process: evidence from a small firm study. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 2(2), pp.59-70.

- Sik, K. W., & Myong, L. K. (1999). A Modern History of Taekwondo. Bokyung Moonhwasa.—42 с.

- Sojka, J.Z. & Fish, M.S.B. (2008) Brief In-Class Role Plays: An Experiential Teaching Tool Targeted to Generation Y Participants, Marketing Education Review, (18, 1), pp25-31

- Southwick, R. (1998) [Retrieved June 16, 2019] https://msu.edu/~spock/history.html

- WTF, 2016. [Retrieved June 2, 2019] http://www.worldtaekwondofederation.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/124-Qualified-for-Rio-20162016-0417.pdf

- WTF, 2017. [Retrieved 28 April 2019] http://www.worldtaekwondo.org/thomas-bach-visits-muju-for-2017-worlds-praises-taekwondo-for-globalization-and-values/

- WTF, 2019. World Taekwondo Federation Competition Rules & Interpretation, World Taekwondo Federation, Korea [Retrieved 18 August 2019] http://www.worldtaekwondo.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/WT-Competition-Rules-Interpretation-Manchester-May-15-2019.pdf

- Yin, R.K. (2003) Case Study Research: Design and Methods (3rd ed), Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA