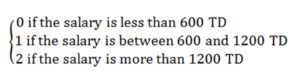

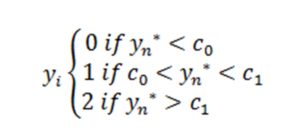

The estimated parameters indicate the impact of a one-unit change in the explanatory variables on the log of the odds ratios. The results show that the employee’s characteristics and those of the company in which they operate, the access and use of ICT at work, the e-skills and the involvement of the employee in new organizational forms are discriminating in classifying the employee in a different wage category.

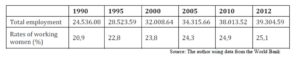

Table 4 shows that the probability of receiving high salary versus average and low salary estimated for male employees is 2.07, which means that being a man raises the probability of receiving a high salary rather than a medium and low salary by twice. In Tunisia, women’s participation in the labor market is still lower than men’s. Their incomes contribute to the household budget as a complement rather than a main income. Thus, they tend to accept lower wages than men. Using Turkish data, Calavrezo and Pelek (2011) support this idea by showing that being a man reduces the likelihood of receiving a minimum wage.

The employee’s age and experience strongly act in favor of higher remuneration. Compared to young employees, being aged between 30 and 40 years (over 40 years) increases the chance of earning a high salary vs low and average salary by 94% (3 times). Professional experience has a similar impact. Hence, an increase by one unit reduces the probability of receiving low wage by about 3% and raises the probability of earning a high salary by about 6%.

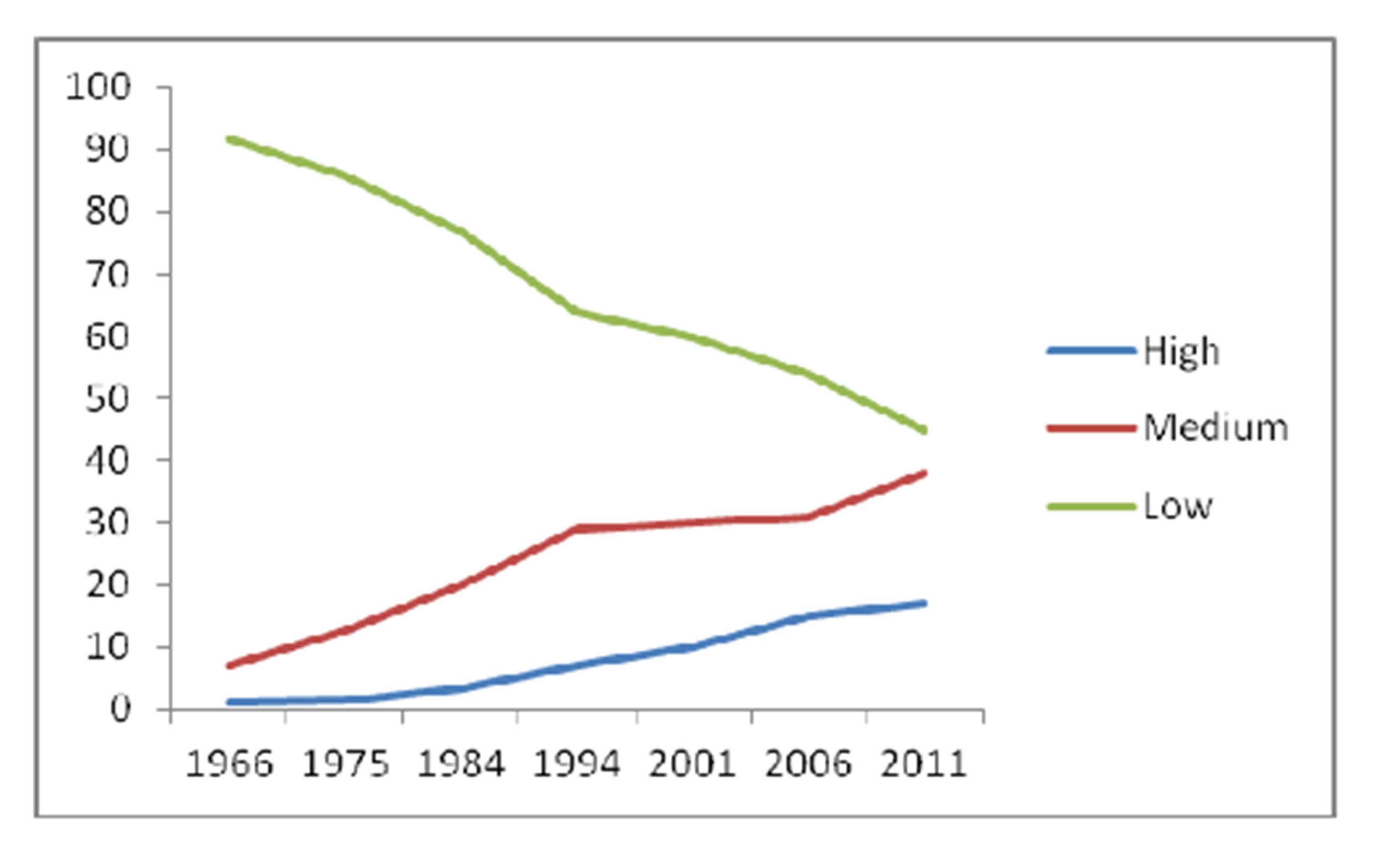

The results also show that education plays a discriminating role in wage determination. The higher educational level is, the more likely to earn high wages. In fact, compared to a high school graduate, a college graduate or post-graduate employee has respectively twice or 4 times as much chance to access a higher salary than a low and average salary. This result is consistent with the economic theory which states that the most skilled workers are better paid, which backs up the existence of a technological bias in favor of skilled workers.

Some features of the firm in which the employee works significantly affect his salary. Therefore, unlike in the administrative sector, working in industry or service sectors raises the employee’s chance of earning a higher pay. It is also clear that, compared to micro-enterprises, working in small and medium enterprises increases the odds ratio by respectively 2 and 4 times to earn a higher salary vs medium and low.

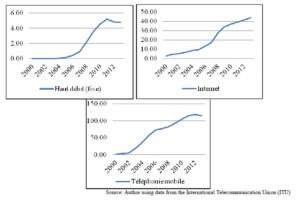

Table 4 also shows that apart from the use of intranet, which shows a highly significant positive impact, the access and intensity of using ICT at work admit no favorable significant effect on the wage development. The odds ratios of high salary versus low and medium salary estimated for the variables telephone and Internet are of about 0.8, which means that the use of the telephone or the Internet by employees at work reduces the odds by 20%. Moreover, an increase in the intensity of the computer and the Internet use (between 2 and 5 hours) reduces by 48% the chance of earning a high salary versus medium and small salary, compared with the use intensity of less than 2 hours per day. This unexpected result is essentially due to the nature of use of these technologies in the workplace and even to that of the work performed by the employee. Actually, when conducting the questionnaire, it appeared that the secretaries and office workers are those who use the phone and the computer more intensively at work whereas the Internet is generally used for leisure (Facebook, Twitter, …) and not for professional reasons. Neither experience in the use of ICT at work, nor the use of the computer (fixed and mobile) and other IT tools will have a significant effect on the evolution of wages.

However, the estimation of our model revealed a positive and significant effect of informational and strategic digital skills on the likelihood of access to high wages (3.1% and 1.7%, respectively). An increase of one unit of the employees’ information skills (strategic) improves the odds of high wages versus low and medium by 1.28 (1.15), which means an increase of the probability by 28% (15%). However, no significant effect was detected for the operational and formal skills on the wage development. This may confirm that, today, wage inequalities caused by the ICT in Tunisia are not an issue of operational and structural manipulation of the hardware and network, but rather a matter of selection, evaluation and use of digital information in a relevant way in order to act on one’s professional life.

Finally, some organizational forms have a positive and highly significant effect on the probability that the employee is classified in a pay grade. The more independent the employee is in carrying out his tasks, the higher the probability of earning a high salary will be. In fact, an increase of one unit of task flexibility improves the odds ratio estimated to reach a higher salary versus low and medium salary of 1.28, which implies an increase of the probability by 28%. Moreover, an increase by a unit of work per project raises the likelihood of having a high salary by about 10% and reduces the probability of earning a low or medium salary of about 5%. Therefore, the dissemination of ICT in the Tunisian firms created a growing need for a more flexible labor force and imposed new requirements for autonomy, self-organization and management tensions. The employee’s involvement in other organizational forms, such as teamwork, job rotation, participation in decision making and cooperation, shows no effect on the evolution of his salary. In Tunisian firms, teamwork and cooperation are often observed among employees, whereas participation in the decision making and job rotation are not quite common organizational forms.

To summarize, the fact that the educational level (1st and 2nd cycle university degree) has a positive and a highly significant effect on the probability of earning a high salary means that the wage gap between the two categories of labor (skilled and unskilled) is beginning to amplify. However, a non-significant overall effect on the access and use of ICT at work raised doubts about the origin of this bias against the less qualified. The highly significant favorable impact of digital skills on the wage development comes to remove these doubts and confirm the existence of a technological bias for the benefit of the more educated workers in Tunisia. It must be said as well that it is not the access or the intensive use of ICT at work that favors some employees compared to others regarding the pay, but it is rather the quality of using the ICT and digital skills of the employee, which accentuates the disparities. Even more, it is the ability to search, select, process and evaluate information based on specific needs and the capacity of using it to achieve specific objectives and improving its position in the company that are at the core of the problem, and not the simple manipulation of digital technology and its structures.

Conclusion

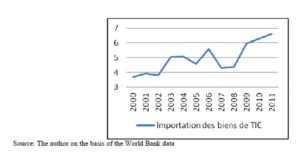

The objective of this article is to examine the impact of ICT on the intra-national inequality and particularly on the wage inequality between the different types of qualifications in a Tunisian context and based on the skill-biased Technological Change hypothesis. The starting point of this analysis is intended to provide a theoretical framework analysis for the phenomenon of the SBTC. Then, after having made some descriptive statistics about the labor market and the diffusion of ICT in Tunisia, we opted for a salary modeling approach to check the existence of a technological bias on the Tunisian labor market. The main results revealed from the estimation of a multinomial ordered logit model on 902 employees working in the industrial, administrative and service sectors are the following.

First of all, the employees’ cognitive skills are a discriminating factor in explaining wage inequality. In fact, an increase in the educational level raises the employee’s chances to access higher wage categories. In addition, greater informational and strategic digital skills entail a higher probability of reaching a higher salary. These results confirm the existence of a technological bias in favor of the better educated on the Tunisian labor market. Then, access and intensity of the ICT use in the workplace do not have a favorable significant effect on the wage development. This means that it is not only the access or intensive use of ICT at work that favors some employees instead of others regarding the wage level, but rather the quality of the ICT use and the employees’ digital skills that contribute to the worsening of inequalities. More fundamentally, it is the ability to search, select, process and evaluate information based on specific needs and capacity to use it in achieving one’s specific objectives and improve one’s position in the company that are at the heart of the problem, rather than the simple manipulation of digital technology and its structures.

Finally, some organizational forms also contribute to the deepening of the existing wage inequalities. In fact, the likelihood of earning a high versus low and medium salary is so high that the employee is independent in performing his tasks and that he works per project. However, several other types of organizations (teamwork, job rotation, participation in decision making, cooperation) have no significant effect on the evolution of wages. This reflects a weakness in the organizational work in the Tunisian firms. However, as stated by M’Henni and Methamem (2008), ICT investment will be counter-productive if it is not accompanied by organizational change. In this regard, we believe that policy makers and companies’ management should pay more attention to the work organization within firms. Moreover, we highlight the importance of establishing a training system in the field of ICT to improve the employees’ digital skills and then fight the amplification of pay inequalities that might result from the diffusion of the ICTs and work organization.

References

1. Acemoglu, 2001. Directed Technical Change. NBER Working Pape, Issue 8287.

2. Acemoglu, D., 1998. Why Do New Technologies Complement Skills? Directed Technical Change and Wage Inequality. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 113(4), pp. 1055-1089.

3. Acemoglu, D., 2007. Equilibrium bias of technology. Econometrica, 75(5), p. 1371—1409.

4. Aghion, P. & Williamson, J. C., 1998. Growth, Inequality and Globalization: Theory, History and Policy. New York and Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

5. Askenazy, P. & Gianella, C., 2000. Le paradoxe de la productivité: les changements organisationnels, facteur complémentaire à l’informatisation. Economie et Statistiques, Issue 339-340, pp. 219-242.

6. Bartel, A. P. & Sicherman, N., 1997. Technological Change and Wages: An inter-Industry analysis. NBER Working Paper, Issue 5941.

7. Bauer, T. K. & Bender, S., 2002. Technological Change, Organizational Change,. IZA Discussion Paper, Issue 570.

8. Benghozi, P.-J. & Cohendet, P., 1997. L’organisation de la Production et de la Décision face aux TIC. Dans: Rapport du Commissariat Général du Plan. s.l.:s.n.

9. Black, P., Harrison, C., Lee, C. & Marshall, B. a. W. D., 2003. Assessment for learning-putting it into practice. Maidenhead, U.K.: Open university Press.

10. Black, S. E. & Lynch, L., 2001. How to compete: the impact of workplace practices and information technology on productivity. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 83(3), pp. 434-445.

11. Boughzala, M., 2013. Youth employment and economic transition in Tunisia”. Global Economy and Development, Working Paper, Issue 57.

12. Bresnahan, T. F., Brynjolfsson, E. & Hitt, L. M., 2002. Information technology, workplace organization and the demand for skilled labor: firm-level evidence. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(1), pp. 339-376.

13. Brotcorne, P. & Valenduc, G., 2009. Les compétences numériques et les inégalités dans les usages d’Internet. Comment réduire ces inégalités?. Les Cahiers du Numérique, 5(1), pp. 45-68.

14. Bué, J., Guignon, N., Hamon-Cholet, S. & L.Vinck, 2002. Vingt ans de conditions de travail”. Données Sociales- La société française, INSEE.

15. Calavrezo, O. & Pelek, S., 2011. Qui sont les salariés payés au salaire minimum? Une analyse empirique à partir des données turques. Document de travail, Issue 139.

16. Card, D. & DiNardo, J. E., 2002. Skill-Biased Technological Change and Rising Wage Inequality: Some Problems and Puzzles. Journal of Labor Economics, 20(4).

17. Caroli, E. & Reenen, J. V., 2001. Skill biased organizational change? Evidence from a panel of british and french establishments. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116(4), pp. 1449-1492.

18. Chan, K., Zhou, X. & Pan, Z., 2014. The growth and inequality nexus: The case of China. International Review of Economics & Finance, 34(C), pp. 230-236.

19. Conte, A. & Vivarelli, M., 2007. Globalization and Employment: imported Skill Biased Technological Change in Developing Countries. IZA Discussion Paper, Issue 2797.

20. Crifo, P., 2003. La modélisation du changement organisationnel : déterminants et conséquences sur le marché du travail. Actualité Economique, 79(3), pp. 349-365.

21. Deursen, A. v. & Dijk, J. v., 2010. Measuring Internet Skills. International journal of human-computer interaction, 26(10), pp. 891-916.

22. Ghazali, M., 2009. Trade Openness and Wage Inequality Between Skilled and Unskilled Workers in Tunisia. Économie internationale, Issue 117, pp. 63-97.

23. Greenan, N., 1996. Progrès technique et changement organisationnel: leur impact sur l’emploi et les qualifications. Economie et Statistiques, Issue 298, pp. 35-44.

24. Greenan, N. & Walkowiak, E., 2005. Informatique, Organisation du travail et Interaction sociales. Economie et Statistiques, Issue 387.

25. Haan, J. d., 2003. IT and Social Inequality in the Netherlands. IT & Society, 1(4), pp. 27-45.

26. He, H. & Liu, Z., 2008. Ivestment-specific technogical change, skill accumulation, and wage inequality. Review of Economic Dynamics, 11(2), p. 314—334.

27. Henderson, D. J., Qian, J. & Wang, L., 2015. The inequality—growth plateau. Economics Letters, 128(C), pp. 17-20.

28. Howitt, P. W. & Mayer-Foulkes, D., 2002. R&D, Implementation and Stagnation: A Schumpeterian Theory of Convergence Clubs. NBER Working Paper Series, Issue 9104.

29. Iniguez-Montiel & Javier, A., 2014. Growth with Equity for the Development of Mexico: Poverty, Inequality, and Economic Growth (1992—2008). World Development, Volume 59, pp. 313-326.

30. International Monetary Fund, 2014. Redistribution, Inequality and Growth, s.l.: s.n.

31. Mincer, J. A., 1974. Schooling, Experience, and Earnings. New York: Columbia University Press for the National Bureau of Economic Research.

32. OCDE, 2014. Focus – Inégalités et croissance — décembre 2014, s.l.: s.n.

33. Quinet, A., 2000. Nouvelles technologies, nouvelle économie et nouvelles organisations. Économie et Statistique, Issue 339-340, pp. 3-14.

34. Saafi, S., 2012. Effets des Innovations Technologiques sur L’emploi Industriel: Essai D’analyse à Partir du Cas Tunisien, France: Université du Littoral-Lille Nord de France.

35. Winchester, N. & Greenaway, D., 2007. Rising wage inequality and capital skill complementarity. Journal of Policy Modeling, 29(1), p. 41—54.