Introduction

Over the past decade, SWFs have become a major player in the global economic landscape with their huge assets under management (Megginson and Gao, 2020; Aggarwal and Goodell, 2018). Different definitions of SWFs were proposed, and a universal agreement about the precise meanings of SWFs does not exist yet (Park, Xu, In and Ji, 2019; Amar, Candelon, Lecourt and Xun, 2019; Akyol and Çiçen, 2017; Rozanov, 2011, etc.). The International Monetary Fund (2008) (IMF) broadly defines SWFs as “government-owned investment funds, set up for a variety of macroeconomic purposes”[1]. Nevertheless, the Sovereign Wealth Fund Institute (2020) (SWFI) defines them more specifically as: “a state-owned investment fund or entity that is commonly established from Balance of payments surpluses; official foreign currency operations; the proceeds of privatizations; governmental transfer payments; fiscal surpluses; and/or receipts resulting from resource exports. The definition of sovereign wealth fund excludes, among other things: Foreign currency reserve assets held by monetary authorities for the traditional balance of payments or monetary policy purposes; state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in the traditional sense; government-employee pension funds (funded by employee/employer contributions); or assets managed for the benefit of individuals”[2]. SWFs are widely described as a specific and unique group of international investors reflecting the massive return of state intervention in the economy after the 1980s waves of privatization. Megginson and Fotak (2015) report that, while governments privatized about $ 1.48 trillion of their assets between 2001 and 2012, they had also acquired $ 1.52 trillion of new stocks during the same period. However, despite being a state investment vehicle, SWFs follow investment strategies similar to private funds (diversified portfolio, geographic diversification, long-term investments, etc.). Specific literature has investigated the rapid growth of SWFs, the impact of their investments, the determinants of their capital allocation, their benefits, the risks they produce, etc. However, SWFs are still widely misunderstood (Bortolotti, Fotak and Loss, 2017; Dedu and Nitescu, 2014). The main purpose of this paper is to review empirical research related to SWFs. A better understanding of this phenomenon and a profile of the state of research on the subject are provided, and some suggestions for research avenues are proposed.

The Increase in Interest for Sovereign Wealth Funds

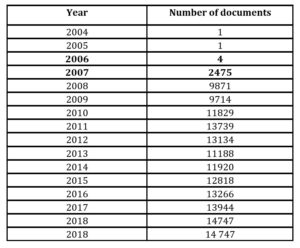

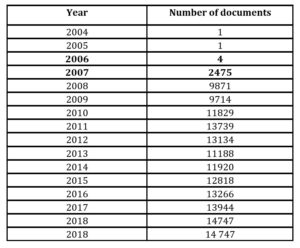

Sovereign Investors have increasingly captured attention and exerted influence in global financial markets. They are not a passing phenomenon. Truman (2007) confirms, “SWFs and similar governmental activities are here to stay.” According to Factiva’s statistics, the number of references about SWFs has increased from 4 in 2006 to 2, 475 in 2007, to 9, 871 in 2008, and has been steadily increasing in recent years (14, 703 in 2018 for example). Table 1 summarizes the number of press papers on SWFs in Factiva database between 2000 and 2018. The search was based on all sources, all authors, all subjects, and all regions and in both English and French languages.

Table 1: Number of Press Papers on SWFs

Source: author’s calculations based on Factiva data.

This rise in interest is mainly due to the rapid growth of SWFs in assets and in number (Megginson and Gao, 2020; Park et al., 2019; Boubaker, Boubakri, Grira and Guizani, 2018; Bortolotti, Fotak and Megginson, 2015; Kotter and Lel, 2011; Balin, 2008; Rozanov, 2005, among other studies). According to SWFI, the SWFs’ assets increased by 59.1% during 2008-2012[3], and today there are more than a hundred funds that manage more than 8 trillion US dollars, a very rapid growth if we consider that their size did not exceed one trillion in 2005 according to Rozanov’s (2005) estimation. Table 2 describes the largest SWFs by assets under management according to SWFI estimation data updated in July 2020 (Sovereign Wealth Fund Name, their country, The Linaburg-Maduell transparency index, their assets under management, their region, their funding sources and the year of inception).

Table 2: Sovereign Wealth Fund Rankings by Total Assets

Source: SWF Institue (Updated July 2020)

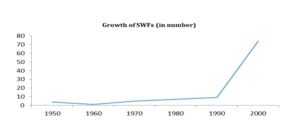

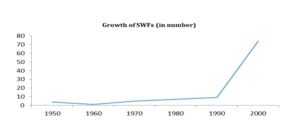

The rapid growth of SWFs is due to high oil prices and current account surpluses, specifically in the Middle East and Asia, as well as the privatization movements of national champions (Jen and Andreopoulos, 2008). In fact, China, which has the largest foreign currency reserve, has the largest non-commodity SWF (940 billion). According to Bortolotti et al. (2017), the aggregated size of all SWFs is almost twice the size of the hedge funds and triple the size of the private equity funds. In terms of numbers, more than 70% of all the existing SWFs have been established in the 2000s (see Fig 1).

Fig. 1: SWFs evolution (in number of creation)

Source: author’s calculations based on SWFI database (July 2020).

Otherwise, the increasing interest in SWFs is due to:

(1) The rise of the role of SWFs in the international financial markets particularly during and after the subprime financial crisis. SWFs were first mentioned in the financial press in early 2007 when the China Investment Corporation bought a 3 billion $US non-voting stake in the Blackstone group immediately before its IPO. The presence of SWFs in the ownership of international firms was amplified during the 2008 financial crisis when SWFs, mainly those from the Gulf countries, injected more than $ 90 billion to save several Western and American institutions from bankruptcy. According to Fernandes (2011), SWFs hold shares in almost one in five companies worldwide. Norway’s fund, the largest SWFs in the world, is present in over than 9000 companies and alone controls the equivalent of 1.4% of the global market capitalization;

(2) The governmental nature of SWFs. Despite multiple worldwide privatization waves since the 1980s, a recent research highlights the growing role of governments in the economy. SWFs are one of the most powerful arms of government. Their government nature raises fears about potential political and strategic goals with regard to their activities. For example, the confidential agreement between China and Costa Rica. According to this agreement, Costa Rica is looking to cut off its political relationship with Taiwan. In return, China pledges to provide Costa Rica with financial assistance, a free-trade agreement and support for a non-permanent seat on the UN Security Council. China’s financial assistance has been through its SWF SAFE Investment Company Limited;

(3) South-North capital transfers: The capital transmission vector is no longer north to south, but south to north. This change is due, in part, to the balance of power and reveals weaknesses in developed countries (Truman, 2008a);

(4) The lack of transparency and information disclosure of the majority of SWFs: Despite the improvement in the level of transparency of SWFs in the last few years (Megginson and Gao, 2020), several SWFs, especially those from non-democratic countries and emerging markets, still lack transparency (Bortolotti et al., 2017; Truman, 2007, Truman, 2008a, b, Kambayashi, 2007, among others); (see Linaburg-Maduell’s transparency index; table 2);

(5) The break with the traditional investment strategy (treasury bonds) and the move towards riskier and higher asset classes. Indeed, SWFs no longer hide their desire and interest to become direct shareholders in the largest Western and American companies. They invest mainly abroad and follow diversified investment strategies (listed and unlisted equity, real states, etc.). Recently, SWFs are targeting more high-tech industries (Megginson and Gao, 2020). This orientation is probably a strategic choice to facilitate the transfer of technology particularly from countries such as Singapore and South Korea.

For all these reasons, host countries remain concerned and suspicious of SWF investments. These fears were amplified by the negative image conveyed by the financial press and by politicians’ speeches who trigger the alarm against SWFs. Barak Obama, the 44th president of the United States (2008) declared, “I am concerned if these … sovereign wealth funds are motivated by more than just market considerations, and that’s obviously a possibility…”[4]. In the same context, Nicolas Sarkozy, president of France between 2007 and 2012, announced in a speech to business leaders near Annecy, eastern France, “I will not be the French president who wakes up in six months’ time to see that French industrial groups have passed into other hands”[5].

Consequences and Determinants of SWFs Activities: Analysis of Empirical Studies

The question of the implications of SWFs’s investments is highly controversial. For some, SWFs are beneficial. They have a stabilizing effect on the financial markets by following a private investment strategy in the long-term without having short-term financial liabilities. In addition, SWFs as large institutional and state investors may provide an implicit guarantee to the target firms, particularly in times of financial distress (Borisova, Fotak, Holland and Megginson, 2015). For others, SWFs pose a serious threat to the global economic stability and host country national security because their activities are politically motivated (Summers, 2007). Still, others oscillate between the two opinions, confirming the benefits of SWFs and their benign nature while recommending vigilance for their transactions (Balin, 2008; Moshirian, 2008; Mattoo and Subramanian, 2008, etc.). These concerns were mainly based on anecdotal evidence. Indeed, the specific academic research on SWFs is still limited because of their opacity and data availability problems (Fernandes, 2014; In, Park, Ji and Lee, 2013). They focused on the determinants of the investment choices of SWFs and their impact on the performance and value of the targeted firms. The results of these studies are mixed and inconsistent. This can be explained by the use of different definitions of SWFs (broadly versus restricted definition), different methodologies and different sample sizes and SWFs values. An overview of the empirical literature on SWFs’s investments is presented in the following paragraphs.

The Impact of SWFs’s Investments on the Performance of the Target Companies

The impact of SWFs’s investments on the value of the target firms were the most studied relationships in the empirical tests. In general, the research question studied in these studies is as follows: Do sovereign wealth funds as large institutional investors controlled by the state affect the value of the target firms? If yes, positively or negatively? To borrow the terminology of Truman (2010), are SWFs a threat or salvation?

SWFs as institutional investors could affect stock prices by : i) intensive purchases or sales of shares; ii) transactions motivated by non-financial objectives; iii) the exercise of a stabilizing effect; iv) increasing liquidity; v) Improving the governance of the target companies; and vi) increasing agency costs of the target firms (managerial opportunism or control costs). In sum, the studies examined the short-term and long-term effects of SWF investments on the performance of the target firms. Researchers conducted event studies to examine the impact of SWF investments on the short-term performance of the target firms. The results are mainly coherent and consistent. Studies by Bortolotti et al. (2015), Knill, Lee and Mauck (2012a), Kotter and Lel (2011), Dewenter, Han and Malatesta (2010), Sojli and Wah Tham (2011), Fotak, Bortolotti and Megginson (2008), Megginson, Bortolotti, Fotak and Miracky (2009), Bortolotti, Fotak, Megginson and Miracky (2010), Sun and Hesse (2009) and Chhaochharia and Laeven (2010) confirm that the target firms report a significant positive abnormal return as a result of SWF investment announcements. Dewenter et al. (2010) examine the impact of SWF investments and disinvestments on the value of the target firms by analyzing the cumulative abnormal returns. They report that in the short-term, the market reacts positively (negatively) to the investments (divestments) of SWFs. They add that the relationship between SWF investments and the value of firms is a function of the size of the equity investment. This confirms a trade-off between the signalling and monitoring effect and the expropriation effect by SWFs. They also find that the positive market reaction is determined by the degree of transparency of SWFs. Megginson et al. (2009) assess the financial impact of SWF investments on equity markets. By highlighting some similarities between SWFs and other international investment vehicles such as pension funds and mutual funds, these authors confirm that the market is responding positively to the announcements of SWF investments. Chhaochharia and Laeven (2010) argue that for a window of -20 to +10 days around the announcement of the acquisition of SWFs, the cumulative average abnormal return is positively significant (1.6%). Similarly, Kotter and Lel (2011) find that the average cumulative abnormal yield is in the range of 1.95%, 2.15% and 2.45% for windows from 0 to +1, from -1 to + 1 and -2 to +2 days respectively around the date of the investment. The relationship is stronger for firms with financial constraints and for the most transparent SWFs. Sun and Hesse (2009) also support a positive short-term effect of SWF investments on the abnormal returns from the target firms. These confirm that SWFs have a stabilizing effect on the stock markets. Bortolotti et al. (2015) find a positive abnormal return of publicly traded firms as a result of SWF investments, but are lower than comparable private investments (SWF equity discount). However, Beck and Fidora (2008) state that there is no effect on corporate asset prices as a result of block sales of shares by the Government Pension Fund-Global of Norway.

Otherwise, the results of the tests that examine the long-term impact of SWF investments on the value of the target firms are not consistent and are inconclusive. Park et al. (2019), Chhaochharia and Laeven (2010), Fotak et al. (2008), Megginson et al., Bortolotti et al. (2010) and Bortolotti et al. (2015) observe the abnormal negative returns during the post-investment period of SWFs. By calculating the abnormal returns, Fotak et al. (2008) find that the target firms achieve a significantly negative average return of around 41% within two years of investing. Chhaochharia and Laeven (2010) have also found a negative abnormal return in the five years following the investment. Bernstein, Lerner and Schoar (2013), for their part, conclude that the value of firms targeted by SWFs is deteriorating, especially when politicians are involved in the decision-making process. Unlike previous studies, Knill et al. (2012a) have examined the return-to-risk performance of the target firms and found that SWF investment is associated with a reduction in the compensation of risk over the five years following the acquisition. These results partly confirm the concerns about the adverse effects of SWFs on the financial markets.

In contrast, Fernandes (2011) and Fernandes (2014) conclude that the long-term performance of the target firms is improving. They confirm that, contrary to arguments, SWFs expropriate investors and pursue political objectives, the ownership of SWFs appears to contribute to the long-term value of shareholders. They added that the target firms benefit from better monitoring, better access to capital and easier access to foreign product markets. On the other hand, Dewenter et al. (2010) and Sojli and Tham (2011) find no significant effect of SWFs on the long-term performance of the target firms. Also, Kotter and Lel (2011) did not detect any significant change between the operational performance of the target companies and the control sample within three years of the date of the investment. The authors explained these results by the inefficiency of government investments, the passivity of SWFs and the likelihood that they will further entrench managers in the target companies.

These diverging results may reflect the definitional challenges of dealing with SWFs (Rozanov, 2001). The studies do not consider the same definition for SWFs. Therefore, the sample sizes, the value of SWFs, and the number and size of transactions are different. In addition, major studies consider SWFs as homogeneous entities while they are very heterogeneous. They present a different background, different sources of funding, different objectives and different structures. Indeed, according to Table 2, a disparity in the level of transparency of SWFs can be noted. Therefore, it is important to consider a common definition of SWFs and to take into consideration their high heterogeneity in the studies.

Determinants of SWFs Asset Allocation

Chhaochharia and Laeven (2010) appear to be the first to be interested in the empirical analysis of the determinants of the investment choices of SWFs. They used a multiple regression model whose dependent variable is foreign biases. The explanatory variables used represent bilateral differences and similarities between SWFs countries and the target countries, such as i) geographic proximity; ii) cultural proximity (linguistic, religious and ethnic proximity); iii) commercial proximity; iv) industrial proximity, and v) measures of the economic, financial and legal development of the host country (financial market development, judicial efficiency, risk of expropriation, accounting standards, GDP per capita). Based on a sample of 67 SWFs investments, Chhaochharia and Laeven (2010) documented that SWFs invest more in countries with which they have cultural affinities (significant positive relationship between foreign investment and ethnic, religious and linguistic proximity). This result suggests that foreign investments by SWFs seem guided by non-economic objectives that do not coincide with profit maximization. In addition, SWFs seem to be present more in the countries with which they have a commercial partnership and industrial proximity. On the one hand, this suggests that SWFs diversify their investments into industries different from domestic industries. The other variables appear to be insignificant.

On the other hand, researchers have shown that the quality of SWFs’s governance is a factor that affects their geographic diversification strategies. Indeed, the impact of industrial diversification only exists for SWFs whose governance score exceeds the median of Truman’s governance score (2008). Thus, the religious bias exists only for SWFs whose governance score is lower than the median of Truman’s governance score (2008). Kotter and Lel (2011) argue that SWFs are similar to passive institutional investors in their investment choices. Using multivariate logistic analysis, the authors show that transparent SWFs prefer to invest in large firms that perform less well and have financial difficulties. In addition, SWFs target developed countries during periods of crisis. Similarly, Fernandes (2011) finds that SWFs are more likely to target larger firms with significant external visibility. Chhaochharia and Laeven (2010) show that SWFs are attracted to strategic sectors (oil sector, for example) and to countries with strong legal institutions to mitigate concerns about politic objectives and wealth expropriation. Knill, Lee and Mauck (2012b) raise the issue of political relations in the SWFs’s asset allocation strategies. These authors find that political relations are an important factor in deciding where SWFs invest, but they are less important in determining the size of the investment. Also, SWFs prefer to invest in countries with which they have weaker political relations, which goes against the theory of foreign investment. These results confirm that the investment objectives of SWFs are not only economic. Dyck and Morse (2011) confirm that political motivations explain the investment profile of SWFs. Bernstein et al. (2013) announce that SWFs are more focused on their country of origin when politicians are more involved in the decision-making process. Ciarlone and Miceli (2014) conclude that SWFs, like the majority of rational investors, prefer to invest in countries with a stable economic environment with developed and liquid financial markets, as well as in countries whose institutions offer investors better protection of legal rights. However, SWFs seem to target countries that are most affected by economic crisis. This type of behaviour may suggest non-economic investment motives.

For Johan, Knill and Mauck (2013), SWFs act differently from other traditional institutional investors when investing in private firms. In fact, when it comes to investing in private firms, SWFs are more likely to invest in countries where the investor protection is low and the bilateral political relations between the two countries are weak. Megginson, You and Han (2013) argue that countries with developed capital markets and a high level of investor protection are more attractive for SWFs. In addition, SWFs countries with high levels of openness and economic development, but with less developed capital markets, are investing more abroad. Boubakri, Cosset and Grira (2016) compared the capital allocation of SWFs with pension funds. They showed that SWFs prefer firms that operate in strategic sectors and have high performance, and firms originating from countries with weaker legal and institutional environments and greater economic growth. Finally, Amar et al. (2019) find that SWFs prefer to invest in countries with a higher political stability.

Conclusion

This study on SWFs provides empirical evidence of the impact of their investments on the performance of their target firms and the determinants of their assets allocation. In sum, the results of the studies are generally consistent when it comes to the effect of SWF ownership in the short-term, but are divergent when it comes to the long-term effect. This indicates that the literature is still mixed and inconsistent regarding the motives (political or economic) and implications of SWF investments. Researchers have been cautious in interpreting results and confirming relationships. The authors noticed that research does not use a common definition of SWFs as a reference, which could partly explain the divergence of the results. Otherwise, studies have largely considered SWFs as homogeneous entities when they are not. SWFs present several differences such as the sources of funding, their origin, their goal for creation, their organizational structure, their degree of dependence on governments, their quality of governance, their level of transparency, etc. Further studies are needed, and it is important to vary research contexts and analytical frameworks. Some research ideas are proposed such as the impact of SWF ownership on acquisition premiums, the quality of information disclosure, the cost debt of the target firms, etc. Similarly, an empirical analysis that discusses investment choices related to the level of political connection of the target firms could also add to the understanding of the determinants of the investment choices of SWFs.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

References

- Aggarwala, R., Goodell, J.W. (2018), ‘Sovereign wealth fund governance and national culture,’ International Business Review, 27, 78-92.

- Akyol, M., and ÇİÇEN, Y. B. (2017), ‘The role of institutional factors when determining investment strategies of sovereign wealth funds in stock market,’ Turkish Economic Review, 4(3), 334–342.

- Amar, J., Candelon, B., Lecourt, C. and Xun, Z. (2019), ‘Country factors and the investment decision-making process of sovereign wealth funds,’ Economic Modelling, 80, 34-48.

- Balin, B J. (2008), ‘Sovereign Wealth Funds: A Critical Analysis,’ John Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies.

- Beck, R and Fidora, M. (2008), ‘The Impact of Sovereign Wealth Funds on Global Financial Markets,’ Intereconomics, 43(6), 349-358.

- Bernstein, S., Lerner, J., and Schoar, A. (2013), ‘The Investment Strategies of Sovereign Wealth Funds,’ The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 27(2).

- Borisova, G., Fotak, V., Holland, K., and Megginson, W. L. (2015), ‘Government Ownership and the Cost of Debt: Evidence from Government Investments in Publicly Traded Firms,’ Journal of Financial Economics, 118(1), 168-191.

- Bortolotti, B., Fotak, V., and Loss, G. (2017), ‘Taming Leviathan: Mitigating Political Interference in Sovereign Wealth Funds’ Public Equity Investments,’ BAFFI CAREFIN Centre Research Paper, 64.

- Bortolotti, B., Fotak, V., and Megginson, W. L. (2015), ‘The Sovereign Wealth Fund Discount: Evidence from Public Equity Investments,’ The Review of Financial Studies, 28(11), 2993-3035.

- Bortolotti, B., Fotak, V., Megginson, W. L., and Miracky, W. (2010), ‘Quiet Leviathans: Sovereign Wealth Fund Investment, Passivity, and The Value of The Firm,’ Unpublished working paper. University of Oklahoma and Sovereign Investment Lab.

- Boubaker, S., Boubakri, N., Grira J., and Guizani A. (2018), ‘Sovereign wealth funds and equity pricing: Evidence from implied cost of equity of publicly traded targets,’ Journal of Corporate Finance, 53, pp. 202–224.

- Boubakri, N., Cosset, J. C., and Grira, J. (2017), ‘Sovereign wealth funds investment effects on target firms’ competitors,’ Emerging Markets Review, 30, 96-112.

- Chhaochharia, V and Laeven, L. (2010), ‘The Investment Allocation of Sovereign Wealth Funds,’Centre for Economic Policy Research.

- Ciarlone, A., and Miceli, V. (2014). Are Sovereign Wealth Funds Contrarian Investors? [Retrieved May 22, 2016], : https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2550736.

- Dedu, V and Nițescu, D. C. (2014), ‘Sovereign Wealth Funds, Catalyzers for Global Financial Markets,’ Theoretical and Applied Economics, XXI (2), 7-18.

- Dewenter, K. L., Han, X., and Malatesta, P. H. (2010), ‘Firm Values and Sovereign Wealth Fund Investments,’ Journal of Financial Economics, 98(2), 256-278.

- Dyck, A and Morse, A. (2011), ‘Sovereign Wealth Fund Portfolios. In Chicago Booth Research Paper.

- Fernandes, N (2014), ‘The Impact of Sovereign Wealth Funds on Corporate Value and Performance,’ Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 26(1), 76–84.

- Fernandes, N. (2011), ‘Sovereign Wealth Funds: Investment Choices and Implications Around the World,’ [Retrieved June 18, 2014],: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1341692.

- Fotak, V., Bortolotti, B., and Megginson, W. (2008), ‘The Financial Impact of Sovereign Wealth Fund Investments in Listed Companies. [Retrieved May 26, 2012],: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/241758435_The_Financial_Impact_of_Sovereign_Wealth_Fund_Investments_in_Listed_Companies

- (2008), ‘Sovereign wealth funds –A work agenda’, IMF.

- In, F., Park, R. J., Ji, P. I., and Lee, B. S. (2013), ‘Do Sovereign Wealth Funds Stabilize Stock Markets? ,’ Asia-Pacific Journal of Financial Studies Conference.

- Jen, S., and Andreopoulos, S. (2008), ‘SWFs: Growth Tempered—US$10 Trillion by 2015,’ Morgan Stanley Research.

- Johan, S. A., Knill, A., and Mauck, N. (2013), ‘Determinants of Sovereign Wealth Fund Investment in Private Equity Vs Public Equity,’ Journal of International Business Studies, 44(2).

- Kambayashi, S (2007), ‘The World’s Most Expensive Club. The Economist.

- Knill, A. M., Lee, B. S., and Mauck, N. (2012a), ‘Sovereign Wealth Fund Investment and the Return-to-risk Performance of Target firms,’ Journal of Financial Intermediation, 21(2), 315-340.

- Knill, A., Lee, B.-S., and Mauck, N. (2012b), ‘Bilateral Political Relations and Sovereign Wealth Fund Investment,’ Journal of Corporate Finance, 18(1), 108-123.

- Kotter, J. and Lel, U. (2011), ‘Friends or Foes? Targets Election Decisions of Sovereign Wealth Funds and their Consequences,’ Journal of Financial Economics, 101,360-381.

- Mattoo, A and Subramanian, A. (2008), ‘Currency Undervaluation and Sovereign Wealth Funds: A New Role for the World Trade Organization. [Retrieved May 22, 2010], : https://www.piie.com/publications/working-papers/currency-undervaluation-and-sovereign-wealth-funds-new-role-world-trade

- Megginson, W. L., and Gao, X. (2020), ‘The State of Research on Sovereign Wealth Funds,’ Forthcoming, Global Finance Journal, 44.

- Megginson, W. L., Bortolotti, B., Fotak, V., and Miracky, W. (2009) , ‘ Sovereign Wealth Fund Investment Patterns and Performance,’ Retrieved from: http://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:fem:femwpa:2009.22.

- Megginson, W. L., You, M., & Han, L. (2013). Determinants of Sovereign Wealth Fund Cross-Border Investments. The Financial Review, 48(4), 539–572.

- Megginson, WL and Fotak, V. (2015), ‘Rise of the Fiduciary State: A Survey of Sovereign Wealth Fund Research,’ Journal of Economic Surveys, 29, 4,733–778.

- Moshirian, F (2008), ‘Sovereign Wealth Funds and Sub-Prime Credit Problems. Retrieved from: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1275226.

- Park, R.J., Xu, S., In, F. and Ji, P.I. (2019), ‘The long-term impact of sovereign wealth fund investments,’ Journal of Financial Markets, 45, 115-138.

- Rozanov, A. (2005), ‘Who Holds the Wealth of Nations? ,’ Central Banking Quarterly Journal, 15(4).

- Rozanov, A. (2011), ‘Definitional Challenges of Dealing with Sovereign Wealth Funds., ’ Asian Journal of International Law, 1, 249–265.

- Sojli, E and Tham, W. W. (2011), ‘The Impact of Foreign Government Investments: Sovereign Wealth Fund Investments in the United States,’ In N. Boubakri and J.-C. Cosset (Eds.), Institutional Investors in Global Capital Markets (pp. 207 – 243): Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Summers, L (2007), ‘Funds That Shake Capitalist Logic,’ Financial Times.

- Sun, T. & Hesse., H. (2009) , ‘ Sovereign Wealth Funds and Financial Stability—An Event Study Analysis,’ Retrieved from https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2016/12/31/Sovereign-Wealth-Funds-and-Financial-Stability-An-Event-Study-Analysis-23370.

- Truman, E M (2007), ‘Sovereign Wealth Fund Acquisitions and Other Foreign Government Investments in the United States: Assessing the Economic and National Security Implications Retrieved from: https://piie.com/publications/papers/truman1107.pdf

- Truman, E M (2008a), ‘A Blueprint for Sovereign Wealth Fund Best Practices,’ Revue d’économie financière (English ed.), 9(1), 429-451.

- Truman, E M (2008b), ‘The Rise of Sovereign Wealth Funds: Impacts on US Foreign Policy and Economic Interests. Retrieved from https://piie.com/commentary/testimonies/rise-sovereign-wealth-funds-impacts-us-foreign-policy-and-economic-interests

- Truman, E M (2010), ‘Sovereign Wealth Funds: Threat or Salvation? Peterson Institute for International Economics. ’

[1] IMF.(2008), ‘Sovereign wealth funds –A work agenda’, IMF.

[2] https://www.swfinstitute.org/research/sovereign-wealth-fund

[3] Source : http://www.swfinstitute.org/sovereign-wealth-fund/.

[4] http://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-sovereignwealth-obama-idUSN0742347120080208

[5] https://www.ft.com/content/e1f97c38-a10d-11dd-82fd-000077b07658