Introduction

In the context of international accounting harmonisation, and through Regulation No. 1606/2002/EC of the European Parliament and the Council of July 19, entities in Portugal with securities admitted to trading on a regulated market have been obliged, since 1 January 2005, must prepare their consolidated financial statements (FS) under international accounting standards (NIC, in the Portuguese acronym). These standards are based on the International Accounting Standards (IAS) and International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) issued by the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) previously endorsed by the European Union (EU) under that Regulation. This also allowed extending the scope of these rules to other entities, a matter that was considered by national legislation through Decree-Law (DL) No. 35/2005 of February 17.

Thus, also the securities issuers that do not present consolidated accounts have to submit, from 2007, their individual accounts in accordance with the IAS, through Regulation No. 11/2005 of the Securities Market Commission. In addition, and as mentioned, DL No. 35/2005, subsequently revoked by DL No. 158/2009 of July 13, extended the scope of IAS, optionally, to the consolidated accounts of the non-issuer entities, as well as to the individual accounts of the entities included in the consolidation perimeter of others that adopt NIC, compulsorily or optionally.

The introduction of the Accounting Standardisation System (SNC, in the Portuguese acronym), by DL No. 158/2009, based on NIC, sought, through convergence, to include Portugal in the context of international accounting harmonization, in a more direct way than previously with the Official Accounting Plan (POC, in the Portuguese Acronym).

The first version of the POC was published in 1977 by DL 47/1977 of February 27. Subsequently, and in order to adapt the POC to the requirements of the EU Directives on the annual (individual) accounts of certain forms of society (Fourth Council Directive No 78/660/EEC of 25 July 1978), a new version of the POC was published in 1989, through DL 410/1989 of November 21, when Portugal was already part of the EU, formerly known as the European Economic Community (EEC). Other important changes followed this. Among these, two stand out.

The first concerns the introduction of DL 238/1991 of July 2, to incorporate the European Directive on Consolidated Accounts (Seventh Council Directive 83/349/EEC of June 13). The second, through the same DL 35/2005 mentioned above, incorporating Directive 2003/51/EC of the European Parliament and the Council of June 18, which is responsible, among others, for the amendment of the Fourth and Seventh Directives, and which became known as the Accounts Modernisation Directive.

Although based on NIC, the national standards provided for in the SNC, applicable to entities not covered by the requirement or by the adoption option of NIC from 2009 on, differ from this regulation which is more evident depending on the SNC regime in which such entities are included. There are different levels of standardisation within the SNC depending on the entities size: the so-called ‘general regime’, with more comprehensive requirements, and two more simplified ones for ‘small entities’ and for ‘micro-entities’.

The transposition of Directive 2013/34/EU to Portugal, following the entry into force of the SNC, was carried out through DL 98/2015. This new Directive, in turn, changed Directive 2006/43/EC of the European Parliament and the Council of May 17, on the legal review of annual and consolidated accounts, while revoking the Fourth and Seventh directives already mentioned, on annual (individual) and consolidated accounts of certain forms of society, respectively.

Therefore, and to sum up, it currently coexists in Portugal, in the light of Regulation 1606/2020 and DL 158/2009 (with the amendments given by DL 98/2015), entities that apply the NIC and entities that apply the SNC. The latter, in turn, presents different levels of application depending on the entities’ size. Initially based on NIC, the SNC was subsequently impacted by the European Directive 2013/34, which was not aligned with those standards.

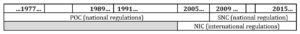

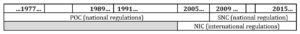

Figure 1 summarizes the historical-normative framework in Portugal from 1977, the year of entry into force of the first POC.

Issue year

National and international regulations applicable in Portugal

Fig. 1. Synthesis of the historical-normative framework in Portugal

It is possible to observe, from Figure 1, that the POC, regardless of the different changes, was in force in Portugal for about 32 years, and there was still a period of five years in which it remained in force even after the introduction of NIC. In other words, the POC (in addition to some sectoral POC) was, in general terms, the only regulation applicable to national non-financial entities for about 27 years.

The SNC, which succeeded the POC and was initially based on NIC, has been in force for about 12 years, a period already coincident, in its entirety, with the latter normative. It can be noted that NIC are applicable to national entities under Regulation 1606/2002, and related national legislation, for about 17 years.

Given this framework, this exploratory study aims to verify whether, even after 17 years of the NIC introduction in Portugal, there is still a potential cultural influence of the POC, based on textual references to linguistic concepts and expressions that only existed during more than 30 years of this standard lifetime. To this end, the most recent consolidated financial reports (2020 or 2021, when available) of the entities listed in Euronext Lisboa will be assessed, which must be prepared under NIC.

This study aims to assess the potential long-term effects of the ‘accounting culture’ sedimented in POC on the materialization of the concepts laid down in the IAS/IFRS. These effects should not be neglected by regulatory and supervisory bodies and should be the basis for discussion on the barriers to international accounting harmonisation and, consequently, to the comparability of financial reporting. As such, obtaining this evidence presents a potential contribution to the literature on the subject. It should also be noted, as an innovation brought by this study, the lack of national studies, on one hand, and the small number of international studies that used this approach of analysis on the other hand.

The paper is organized as follows. The next section has the literature review on the factors that can be implementation barriers to the IAS/IFRS, namely the influence of culture on accounting practices, with emphasis on issues related to language (especially translation) and interpretation of the concepts translated. The third section presents the materials and methods used and the results obtained, being the last one for conclusions and perspectives for future investigations.

Literature Review

The comparability of financial reporting is one of the main objectives of the international accounting harmonization (Nobes, 2013). Despite the rapid spread of IAS/IFRS, the literature points out the divergences between the so-called de jure harmonization (the standards adoption by entities from different countries) and the de facto harmonization (the effective materialization of these standards in their financial reporting).

Thus, the author argues that the analysis of the countries’ classification around accounting systems remains relevant, suggesting that, in practice, differences in financial reporting can arise from issues such as language and interpretation, local regulation and the options existing in the IAS/IFRS (Nobes, 2013).

There are several factors that the literature identifies as barriers to the introduction or implementation of IAS/IFRS, including issues regarding cultural factors in general, as a globalizing and synthesizer concept. More specifically, it is possible to identify institutional and economic factors inherent to different countries that can be individually identified, such as religion, language, and the level of countries development, which may result in lower levels of training and experience in matters related to these standards.

Silva et al. (2021) concluded, through interviews with agents of the tax authority of Brazil and Portugal, that the maintenance of cultural classification and the code-law framework in which both countries have been proposed are barriers to full de facto harmonization.

In addition to the obstacles to the implementation of IAS/IFRS in different countries, the implementation of local standards converging with these standards has also been the subject of studies. The most recent study carried out in Portugal in this matter was also based on interviews with auditors, identifying that its code-law framework creates barriers to the implementation of the SNC, as well as the existence of a dissociation between formal requirements and real practices (Fontes et al., 2021).

Belkaoui (1978), one of the pioneers in studies associating linguistics and accounting, states that accounting can be seen as a language, since it incorporates characteristics of grammar and lexicon, through symbolic representations such as debt and credit. Thus, there are terms that represent the accounting vocabulary and rules that are its syntax. From this perspective, he identified in later studies (1980, 1984), from experiments involving different groups of users, preparers or students, the absence of consensus on the meaning of certain accounting concepts, presenting arguments that corroborate a sociolinguistic perspective of analysis.

The literature review by Dowa et al. (2017), on the barriers to the implementation of IAS/IFRS, has identified incompatibilities between many of the principles laid down in these standards and the Islamic religion, in addition to the misapplication of these standards, through translation, in countries where English is not the native language. Other relevant factors included insufficient technical knowledge and experience of accountants and auditors in relation to these standards.

Faraj and El-Firjani (2014), through semi-structured interviews with internal auditors of entities listed in Libya, concluded that entities tend to consider, in the preparation of the FS, the commercial, tax or other existing laws before the adoption of the IAS/IFRS. More specifically, they also identified practical issues such as lack of training, lack of preparation or prior knowledge of accountants in this area, the absence of these subjects in the curriculum of the courses, the weak governance mechanisms, and the lack of enforcement by regulators and auditors. Additionally, they identified the difficulty of using the English language in the preparation of accounts by the majority of the participants in the study.

According to the strong structuration theory, and also based on interviews, in this case to members of the regulatory body of the accounting profession in Saudi Arabia, Almusaad (2021) identified the influence of the local context. Similarly, the translation promoted by local authorities, which did not receive comment from the IFRS Foundation, may have been impacted by the subjectivity inherent in these processes.

Through a questionnaire conducted to more than a hundred local translators, Baskerville and Evans (2012) demonstrated the diversity of views that can emerge in this process from the convictions of translators that may contain biases, even among the most experienced ones.

The difference in the development levels of the countries has also to be considered, as it can often be related to the highest or lowest proficiency in the English language. Qualitative studies involving students from English and non-English countries have identified syntax and lexicon problems that may most specifically arise (namely, Baskerville et al., 2016).

Dahlgren and Nilsson (2012), in a study in Sweden, proved that comparability can effectively be compromised in the translation process into a non-English speaking country, suggesting that mere translation is not enough when contexts and specificities are not met.

Despite the previous findings, Evans (2018) points out that the literature has not yet given due importance to problems derived from translation, not being a purely technical issue, but also of a sociocultural, subjective, and ideological order, with implications in several areas, such as regulation, research, and accounting practice.

Evans et al. (2015) stand out, on the other hand, that the ambiguity inherent in translation can contribute to accounting convergence, if properly explored in its ideological or practical aspects in the context of accounting regulation. They also identify that the disregard or underestimation of their effects may possibly be explained by the limited effects they have on stakeholders who are most culturally and economically dominant.

Considering the classification models of the accounting systems proposed by Nobes (1983), the cultural dimensions of Hofstede (1980), Hofstede et al. (2010) or Gray’s cultural values (1988), different studies assess the potential effect from the interpretation of uncertainty or probabilistic expressions present in different IAS/IFRS, including studies that include Brazil and Portugal in this analysis (Doupnik & Salter, 1993; Doupnik & Tsakumis, 2004; Doupnik & Riccio, 2006; Chand et al., 2012; Justino et al., 2015; Ayadi et al., 2020).

No studies were identified, however, using the analysis approach proposed in this exploratory study, presented in the following section.

Methodology and Results

Methodology

The present exploratory study aims to identify the potential long-term effect of the adoption of the POC for more than 30 years, materialized through an overlap of the concepts laid down in the IAS/IFRS.

This paper uses data from Euronext Lisbon, the Portuguese stock exchange, which includes an index for all entities, the PSI All-Share Index, and an index composed of the most representative entities, the PSI 20. The latter integrates more than 98% of the total market capitalization, despite contemplating less than half of the entities listed in the PSI All-Share Index (Euronext, 2021). All listed entities must prepare their FS, mandatorily, under NIC, whose Portuguese-language version is available in different European regulations responsible for the endorsement of IAS/IFRS under Regulation 1606/2002.

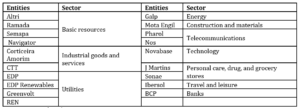

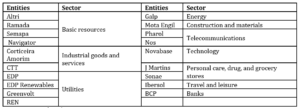

Table 1 shows the PSI 20 entities and the corresponding activity sector, based on the 4-digits (super sector) of Industry Classification Benchmark (ICB).

Table 1. Entities that make up PSI 20 and its sectors as of December 31, 2021

Source: Euronext (2021)

Source: Euronext (2021)

The most recent consolidated FS (year 2021, and six of 2020 when it was the last year available) were collected in the first half of April 2022, from the websites of the PSI 20 entities, currently composed of 19 entities. Given that EDP Renewables most recent consolidated FS are only available in English, the entity was excluded from the study. Thus, the analysis focused on 18 entities.

From the ICB, evidence will be sought, in the subsequent analysis, on different patterns of accounting practice according to the entities’ activity sector.

Results

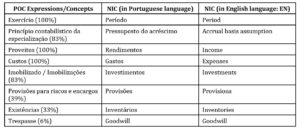

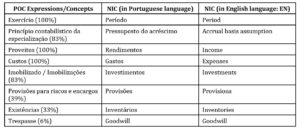

The analysis identified textual references to various concepts and linguistic expressions that only existed under POC, which were synthesized in Table 2 (in brackets, the percentage of total entities that use them).

Table 2. Principal concepts and linguistic expressions of the POC identified

(and comparison with NIC)

Although the NIC adopted the term ‘período’ (‘period’ in EN), it is observed that ‘exercício’, the Portuguese term used in POC, continues to be presented by all entities studied in different expressions. Then, the net income of the ‘exercício’, income tax of the ‘exercício’, amortisations of the ‘exercício’ or account and reports of the ‘exercício’ can be seen for those entities, instead of ‘period’.

Under NIC, the current concept of ‘pressuposto do acréscimo’ (‘accrual basis assumption’ in EN) replaced the previous concept of ‘princípio contabilístico da especialização dos exercícios’ or similar under POC, meaning ‘accounting principle of accrual basis’ in a non-literal translation in EN. It means that, besides the different designation, there is also a different framework for this concept since then: as an assumption, instead of an accounting principle. Despite that, it can be seen that the previous concept continues to be pointed out by most of these entities (only two do not do it) to justify the economic periodization of their incomes and expenses. Furthermore, their income and expenses are sometimes mentioned as ‘proveitos’ instead of ‘rendimentos’ (‘income’ in EN) and ‘custos’ instead of ‘gastos’ (‘expenses’ in EN), respectively.

Consequently, in the identification of the entities accounting policies, some excerpts can be observed very close to the POC conceptualization, such as:

- Borrowing costs are usually recognised as ‘custos’ in the income statement in accordance with the ‘princípio da especialização dos exercícios’;

- Interests are recognised in accordance with the ‘princípio da especialização dos exercícios’;

- Maintenance and repair costs are recognised as ‘custos’ as they are incurred according to the ‘princípio da especialização dos exercícios’.

There is also a combination of POC and the proper NIC terminology, particularly in the following quotes:

- ‘Rendimentos’ and ‘gastos’ are recorded in the period to which they relate, regardless of their payment or receipt, according to the principle of the ‘especialização dos exercícios’

- ‘Rendimentos’ and ‘gastos’ are recorded according to the assumption of the ‘especialização dos exercícios’, so they are recognized as they are generated, regardless of the time they are received or paid.

It is worthwhile to stress that terms such as ‘proveitos’ (instead of ‘rendimentos’) or ‘custos’ (instead of ‘gastos’), with the meaning of ‘incomes’ and ‘expenses’ in EN, respectively, are not occasional and, oppositely, can be found in the FS of all entities.

Concerning ‘proveitos’, expressions such as interest and similar ‘proveitos’, other ‘proveitos’, supplementary ‘proveitos’ or other operational ‘proveitos’ are observed. Additionally, the ‘rendimentos a reconhecer’ (‘deferred income’ in EN) are often referred to as ‘proveitos diferidos’ or ‘proveitos a reconhecer’, both with the meaning of ‘deferred income’, combining the current and old nomenclature.

Similarly, and as regards the ‘custos’, there are several references to interest and similar ‘custos’, financial ‘custos’, operational ‘custos’, deferred ‘custos’ and accrued ‘custos’.

It should also be noted that entities use, wrongly even under POC, a different terminology with the meaning of ‘rendimentos’ (‘incomes’ in EN) and ‘gastos’ (‘expenses’ in EN), in particular the terms ‘receitas’ and ‘despesas’, respectively. Below are some examples:

- ‘Receitas’ and ‘despesas’ are recorded according to the principle of the ‘especialização dos exercícios’ by which they are recognised as they are generated regardless of the time at which they are received or paid.

- ‘Receitas’ correspond to the sum of the following items: sales and rendered services; supplementary ‘proveitos’; (…); other operational ‘proveitos’; financial gains and ‘proveitos’; gains with ‘imobilizado’.

Another POC designation that maintains its influence is ‘imobilizado’ to name ‘investments’ in EN. More than 83% of the entities (15 out of 18) maintain this terminology, being the frequent use of ‘imobilizado’ assets, corporeal ‘imobilizado’ (with the meaning of ‘tangible assets’), incorporeal ‘imobilizado’ (with the meaning of ‘tangible assets’), financial ‘imobilizações’, other corporeal ‘imobilizações, work in project ‘imobilizado’, investment grants in ‘imobilizado’, advances for ‘imobilizado’ suppliers, ‘imobilizado’ suppliers or loss in ‘imobilizado’.

In this context, it also appears that, in some cases, the term ‘amortizações’ (‘amortisations’ in EN), with the global meaning of depreciations and amortisations, is incorrectly used as it has been applied for investment assets in general. Under NIC, the term ‘amortizações’/’amortisations’ is only applicable to intangible assets with definite useful life, while depreciations are applicable to tangible fixed assets or investment properties, whenever depreciable. Even when including depreciation amounts, the financial information contains phrases such as “the operational ‘custos’ do not include amortizações” or “amortizações and impairments totalize (…)’, whilst in the income statement, it is only called ‘amortizações’ or ‘amortizações’ and impairments. It was also possible to find a reference to the terminology under POC of 1977 (reintegration) when it is referred a ‘reintegração’ of ‘imobilizado’.

In the context of liabilities, it was possible to observe that, in 39% of the cases, the NIC ‘provisões’ (‘provisions in EN) continue to be designated as ‘provisões para riscos e encargos’, which corresponded to the terminology of the POC of 1989, which ceased with POC 2005. It should be noted that this is the designation which, in some cases, appears in the statement of financial position.

In entities that have ‘inventários’ (‘inventories’ in EN), it is possible to observe, in 38% of the cases, the influence of the previous terminology ‘existências’, with several references to gains in ‘existências’, regularisation of ‘existências’ or final ‘existências’. There is also a mixture of POC and NIC terminology in phrases such as “in transit inventories are segregated from other ‘existências’”.

Even though it is not part of the NIC concepts, there is one entity that continues to use the term ‘trespasse’ (instead of goodwill, in EN), being referred to as acquisition cost of ‘trespasses’ and presented the amortisation rate of ‘trespasses’.

It was not possible to verify, in any of the identified expressions/concepts, that the entities’ sector is a differentiating factor of the followed practice.

Conclusions

Being the comparability of financial reporting, one of the main objectives underlying international accounting harmonization (Nobes, 2013), the literature has discussed the factors that distinguish the adoption of IAS/IFRS (de jure harmonization) and their effective implementation in the FS (de facto harmonization) of entities from several countries.

In this context, the present exploratory study sought to identify terms and expressions that were used over more than 30 years under the previous accounting standards in force in Portugal in the consolidated FS of PSI 20 entities that, at present, must adopt the NIC, introduced 17 years ago. Thus, this analysis aimed to identify evidence of potential long-term effects of an ‘accounting culture’ that materializes through an overlap of the concepts in the IAS/IFRS.

The analysis allowed us to conclude that the application of the POC for more than three decades seems to continue to influence the FS prepared according to the NIC, since textual references to various concepts and linguistic expressions that only existed in that standard were identified. Although the NIC have adopted new terminology, expressions can be still found in the financial information of the analyzed entities, regardless of their activity sector. as the examples include the following cases: ‘proveitos’ (instead of ‘rendimentos’, ‘incomes’ in EN), ‘custos’ (instead of ‘gastos’, ‘expenses’ in EN), ‘imobilizados’ (instead of ‘investimentos’, ‘investments’ in EN), ‘princípio da especialização dos exercícios’ (instead of ‘pressuposto do acréscimo’, ‘accrual basis assumption’ in EN) or ‘provisões para riscos e encargos’ (instead of ‘provisões’, ‘provisions’ in EN),.

This evidence corroborates the most recent studies conducted in Portugal, which, although distinct in terms of their specific objectives, concluded that the code-law framework presents itself as a barrier to a de facto harmonization (Silva et al., 2021; Fontes et al., 2021), also identifying the existence of a dissociation between formal requirements and real practices (Fontes et al., 2021).

As a proposal for future research, it is suggested to carry out similar studies in other countries, namely European countries for which English is not their native language, to find if different national environments and cultures may impact the results.

References

- Almusaad, N.S. (2021). Understanding the factors that influence the IFRS adoption and translation from a Strong Structuration Theory perspective (Doctoral dissertation, University of Essex). http://repository.essex.ac.uk/31451/1/Nada%20Almusaad%20Phd%20Thesis.pdf

- Ayadi, J. E., Damak, S. and Hussainey, K. (2020). ‘The impact of conservatism and secrecy on the IFRS interpretation: the case of Tunisia and Egypt’. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting. Https://pure.port.ac.uk/ws/files/25730136/The_impact_of_Conservatism_and_Secrecy_on_the_IFRS_interpretation.pdf

- Baskerville, R. F. and Evans, L. (2012). Situating IFRS translation in the EU within speed wobbles of convergence. Available at SSRN 2028660. http://researcharchive.vuw.ac.nz/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10063/2097/paper.pdf?sequence=1

- Baskerville, R. F., Xue, Q. and Rhys, H. (2016). ‘How does the English of IFRS challenge an international student cohort? Evidence from a Chinese cohort’. Working paper series. https://www.wgtn.ac.nz/cagtr/working-papers/wp-105.pdf

- Belkaoui, A. (1978). ‘Linguistic relativity in accounting’. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 3(2), 97-104. https://doi.org/10.1016/0361-3682(78)90019-3

- Belkaoui, A. (1980). ‘The interprofessional linguistic communication of accounting concepts: an experiment in sociolinguistics’. Journal of Accounting Research, 362-374. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2490583

- Belkaoui, A. (1984). ‘A test of the linguistic relativism in accounting’. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences/Revue Canadienne des Sciences de l’Administration, 1(2), 238-255. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1936-4490.1984.tb00289.x

- Chand, P., Cummings, L. and Patel, C. (2012). ‘The effect of accounting education and national culture on accounting judgments: A comparative study of Anglo-Celtic and Chinese culture’. European Accounting Review, 21(1), 153-182. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638180.2011.591524

- Dahlgren, J. and Nilsson, S. A. (2012). ‘Can translations achieve comparability? The case of translating IFRSs into Swedish’. Accounting in Europe, 9(1), 39-59. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449480.2012.664391

- Decree-law 47 of 1977. (1977, February 7). Ministries of Economic and Finance Plan and Coordination. Diary of the Republic. Series I No. 31. https://dre.tretas.org/dre/14438/decreto-lei-47-77-de-7-de-fevereiro#anexos

- Decree-law 410 of 1989. (1989, november 21). Ministry of Finance. Diary of the Republic. Series I No. 268-supplement. https://dre.tretas.org/dre/21953/decreto-lei-410-89-de-21-de-novembro

- Decree-law 238 of 1991. (1991, July 2). Ministry of Finance and Justice. Diary of the Republic. Series I-A No. 149. https://dre.tretas.org/dre/27253/decreto-lei-238-91-de-2-de-julho

- Decree-law 35 of 2005. (2005, february 17). Ministry of Finance and Public Administration. Diary of the Republic. Series I-A No. 34. https://dre.pt/dre/detalhe/decreto-lei/35-2005-605330

- Decree-Law 158 of 2009. (2009, july 13). Ministry of Finance and Public Administration. Diary of the Republic. Series I-A No. 133. https://dre.pt/dre/detalhe/decreto-lei/158-2009-492428.

- Decree-law 98 of 2015. (2015, june 2). Ministry of Finance. Diary of the Republic. Series I-a No. 106. https://dre.pt/dre/detalhe/decreto-lei/98-2015-67356342

- Directive 660 of 1978. (1978, July 25). From the Council. Official Journal of the European Communities L 222. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PT/ALL/?uri=celex:31978L0660

- Directive 349 of 1983. (1983, June 13). From the Council. Official Journal of the European Communities L 193. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PT/TXT/?uri=celex%3A31983L0349

- Directive 51 of 2003. (2003, june 18). The European Parliament and the Council. Official Journal of the European Communities L 178. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PT/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32003L0051&from=SK

- Directive 43 of 2006. (2006, May 17). The European Parliament and the Council. Official Journal of the European Communities L 157. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PT/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32006L0043&from=BG

- Directive 34 of 2013. (1983, June 26). The European Parliament and the Council. Official Journal of the European Union L 182. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PT/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32013L0034&from=NL

- Dowa, A., Elgammi, A.M., Elhatab, A. and Mutat, H. A. (2017). ‘Main worldwide cultural obstacles on adopting international financial reporting standards (IFRS)’. International Journal of Economics and Finance, 9(2), 172. http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ijef.v9n2p172

- Doupnik, T. S. and Riccio, E. L. (2006). ‘The influence of conservatism and secrecy on the interpretation of verbal probability expressions in the Anglo and Latin cultural areas’. The International Journal of Accounting, 41(3), 237-261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intacc.2006.07.005

- Doupnik, T. S. and Salter, S.B. (1993). ‘An empirical test of a judgemental international classification of financial reporting practices’. Journal of international business studies, 24(1), 41-60. http://www.jstor.com/stable/154970

- Doupnik, T. S. and Tsakumis, G. T. (2004). ‘A critical review of tests of Gray’s theory of cultural relevance and suggestions for future research’. Journal of Accounting Literature, 23, 1. https://www.proquest.com/openview/7121061381ea2d9e37ee75a1a7404210/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=31366.

- (2021). PSI 20 Factsheet. Accessed in https://live.euronext.com/en/product/indices/PTING0200002-XLIS/market-information

- Evans, L. (2018). ‘Language, translation and accounting: towards a critical research agenda’. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-08-2017-3055

- Evans, L., Baskerville, R. and Nara, K. (2015), Colliding Worlds: Issues Relating to Language Translation in Accounting and Some Lessons from Other Disciplines. Abacus, 51:1–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/abac.12040

- Faraj, S. and El-Firjani, E. (2014). ‘Challenges facing IASs/IFRS implementation by Libyan listed companies’. Universal Journal of Accounting and Finance, 2(3), 57-63. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujaf.2014.020302

- Fontes, A. S., Rodrigues, L. L., Marques, C. and Silva, A. P. (2021). ‘Barriers to institutionalization of an IFRS-based model: perceptions of Portuguese auditors’. Meditari Accountancy Research. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEDAR-09-2020-1014

- Gray, S., J. (1988). ‘Towards a Theory of Cultural Influence on the Development of Accounting Systems Internationally’. Abacus, 24 (1), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6281.1988.tb00200.x

- Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

- Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., and Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind (3rd. ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- Justino, M. D. R., Albuquerque, F., Texeira-Quirós, J. and Marcelino, M.M. (2015). ‘The Influence of Culture and Professional Judgment on Accounting: An Analysis from the Perspective of Information Preparers in Portugal’. Journal of Education and Research in Accounting, 63-87. http://dx.doi.org/10.17524/repec.v10i1.1214

- Nobes, C. W. (1983). ‘A judgemental international classification of financial reporting practices’. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 10(1), 1-19. 1468-5957.1983.tb00409.x20161118-22012-1k9y1s9-with-cover-page-v2.pdf (d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net)

- Nobes, C. (2013). ‘The continued of survival of international differences under IFRS’. Accounting and Business Research, 43 (2), 83–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/00014788.2013.770644

- Regulation 1606 of 2002. (2002, july 19). European Parliament and the Council. Official Journal of the European Union. L 243. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PT/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32002R1606

- Regulation 11 of 2005. (2005, November 3). Securities And Exchange Commission. Diary of the Republic. Series ii No. https://dre.pt/dre/detalhe/regulamento-cmvm/11-2005-2988657

- Silva, A. P., Fontes, A. and Martins, A. (2021). ‘Perceptions regarding the implementation of International Financial Reporting Standards in Portugal and Brazil’. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation, 44, 100416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intaccaudtax.2021.100416