Introduction

The idea of sharing is not new; it existed since a long time. The Internet and new technologies have considerably increased the expansion of the collaborative economy (Belk, 2014). The great expansion of sharing from local participants and neighbors to unknown and distant strangers is essentially due today to ICT (Schor, 2016).

For many reasons and in different circumstances like wars, catastrophies, difficult economic situations and scarcity, the population regroups have shared the existing resources. The sharing is evolving today from a purely ideological ideal to a more business oriented model, even if the message insists on “making good” through respecting the environment, sociability, fair trade and all other criteria that should characterize the basic spirit. The literature about this phenomenon is abundant, but the conceptual analyses lack precision because this concept is still new compared to others already studied.

The sharing idea has existed for a long time in the Arab world under different forms; it covered different products and services.

Throughout history, many people and communities practiced sharing in different ways in their day-to-day lifestyle. In Lebanon for example, and because of electricity shortages, the power generating sharing business is well across a large part of the population throughout the country. Also for purely economic reasons, the sharing of transportation in Lebanon as well is very popular since many decades long before the proliferation of digital platforms.

Eventually sharing will affect new industries because this economy is spreading to activities that have been spared in the past, thus the sharing logic can integrate all economical activities. Through this strategy, a lot of money will be earned from existing and new industries, which will generate extra revenues to a large portion of the population; however, it might disrupt many sectors along with their workers. The spread of the big sharing platforms is very fast and they cover today almost all areas. Airbnb and Uber are the most well-known sharing companies; they have collected more than $12 billion raised in venture funding since 2007 (BCG, 2017). Other companies are also expanding their activity in their home market, such as Lyft in the US, Didi Chuxing in China and Ola in India.

This new type of business and the social model of exchange of goods and services are challenging our life and our society. As indicated above, sharing is not new but technology and globalization have given to this phenomenon unlimited and unbounded opportunities and potential. Sharing is considered as the normal path of our capitalist system thus we can talk today of an internationalization of the concept with a local adaptation according to different countries, communities and legislation.

Our study aims, beyond the presentation of this new economic model, to probe Lebanese consumers about their interest in this new mode of exchange, its scope and challenges. It also considers investigating the factors affecting the intention of Lebanese consumers to participate in collaborative consumption. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study assessing the perception of the sharing economy in Lebanon.

Hypothesis and Research Model

In order to understand the phenomenon of the sharing economy in Lebanon, we introduced a research model that allowed us to analyze the adoption pattern of this new economy by the consumers. Four forms of sharing are taken into account: Car sharing, Ride sharing, Accommodation sharing and Peer-to-peer financing. We worked on five hypotheses offering significance and accuracy for the choice of the sharing by Lebanese users. Economic benefit, heavy reliance on new technology, community belonging, safety and trust, and user protection, have been chosen for this study.

H1: Economic Benefit is closely related to the use of the Sharing Economy

The economic logic has always been considered as important behind the idea of sharing for both users and proprietors. The price and the cost of the service or the product for users and the economic benefit for owners are key for the adoption of this type of sharing (Lamberton & Rose, 2012). Sharing allows usage and access to different products and services at a lower cost (Sacks, 2011). Its consumption is usually considered cheaper than non-sharing and price criteria decisive for choosing sharing (Moeller & Wittkowski 2010). The competition between hotels and sharing lodging platforms like Airbnb is mainly focused on price and room availability. The impact of Airbnb on local house pricing is clear and significant (Gerdeman, 2018).

H2: Heavy reliance on new technology is closely related to the use of the Sharing Economy

We cannot dissociate the sharing economy from globalization and information and communication technology. The rapid growth of the sharing economy throughout the world is closely linked to the development of information technologies and to the World Wide Web. The usage of the Internet has enabled the development of online platforms that promote user-generated content, sharing, and collaboration (Kaplan & Haenlein, 2010). The ease with which platform customers do business is a very positive factor for a country like Lebanon where online transactions are not sufficiently developed. The fact that the major platforms have a serious reputation reassures those Lebanese users who do not trust online transactions. The big platforms make the customer experience amazing opportunities; Airbnb, for instance, offers the same human touch to the customer as when he goes to the hotel. This experience is done online, but as a user, the customer feels like interacting with someone who cares (Karam, 2016).

H3: Community belonging is closely related to the use of the Sharing Economy

Sharing platforms work on building up a specific identity and a sense of belonging among users (O’Regan, 2013). They put rules to let all participants in the sharing to have a common behavior with the platform (Hamari et al., 2015). Airbnb “community” committed to making the world a more connected and better place, one less stranger at a time, based on shared values of kindness, social and environmental consciousness, responsibility, collaboration and cohesion (Oates, 2015). Users of the sharing economy begin to adopt a specific and common vocabulary when they deal with platforms; a common virtual spirit bloomsome between members of this economy due to the creation of a sense of belonging. The sharing economy sets the human behavior as an alternative to the standard market or to the traditional companies; a human touch is visible in the relation between the platforms and their users. This human touch is characterized by some elements such as the ranking system, the comments, personal data on the service providers and the users. The Strengthening of community belonging is reinforced by the perception of being part of an open-minded group trusting themselves and sharing the same values of openness and acceptance of others. As these networks grow, sharing platforms increasingly encourage new users to align themselves with certain values, shared beliefs and cultural norms that are expressed by the language used by the platforms (Celata et al., 2017).

H4: Safety and trust is closely related to the use of the sharing economy

Trust is considered as a willingness to commit to a collaborative effort before you know how the other person will behave (Coleman, 1990). Sharing platforms put important efforts and develop formal and informal mechanisms to enforce and communicate a sense of reassurance to their “trustworthy” communities of users (Celata et al., 2017). Without a minimum trust, the sharing economy cannot go forward. The digital reputation of a system mainly based on ratings, references and feedback is likely to provide confidence and tranquility for both users and service providers (Ronzhyn, 2013). Learning from the experiences of others publicly available on the platform is considered as beneficial, helping to trust each other. The worldwide explosion of the Sharing Economy can be attributed to the improvements in the ability to get people to trust strangers, thanks to the “digital trust infrastructure” (Sundararajan, 2016). The adherence to a common set of norms and ethical principles (Bardhi & Eckhardt, 2012) among the members and the community of the platform enforces trust. The reputed platforms have created a real global brand enabling them to offer trust and confidence to their actual and potential users.

H5: User protection is closely related to norms and standards, customer protection and government regulation

The world is a safer and more reliable place because regulations exist (Sundararajan, 2016) making users and service providers feel safer, however, at the same time as a new way of doing business, the administrative mechanisms cannot be the same for companies that have been around for a long time. The lack of norms, standards, customer protection and government regulation is a real concern for users, governments and even providers. The point of view and the claims of users and consumers are very important and will lead to the adjustment of the sharing. We are witnessing today a regulatory debate all over the world where the sharing is taking place (Heimans & Timms, 2014). Because the boundaries between the personal and the professional are complicated and sometimes not clear enough (Molly & Sundararajan, 2015), all the actors feel a blurring situation that requires a new approach compatible with the vocation of this new economy.

Research Method

Instrument development and data collection

A nationally representative survey was conducted covering 673 Lebanese adults, interviewed face-to-face with an offline questionnaire developed on ISURVEY application. Participants were included in the study if they were Lebanese, had been living for at least five years from the date of the survey, and aged 18 and over. The respondents were mostly between18-24 years (n = 116), 25-45 years (n = 422), 46 years and more (n = 135). About 49% of the participants were women (n = 330) and 51% were men (n = 343). Data were collected from March 14th 2018 through April 5th 2018, by a team of 8 data collectors overseen by a supervisor.

Ethical considerations

Our study was approved by the ethics committee of the Saint Joseph University of Beirut and by the research council of the university. All participants signed the consent letter before participating in the study. Confidentiality was respected throughout the whole study.

Instrument

The survey questionnaire was developed by using measurements from a variety of academic studies that were adapted to the local context. It contained 49 questions, covering six sets of questions and socio-demographic data.

The first section contains 6 questions about the regularity of Internet use and five types of collaboration consumption, the 8 questions in the second set are related to the benefits of S.E. The third set also included 8 questions related to the potential drawbacks of S.E. 8 questions in the fourth set are related to how participants consider getting involved in S.E. As for the fifth set, it contains seven questions about reasons for not participating in S.E. or stopping using it. The sixth section gathered four questions related to environmental damage, transforming today’s threat into tomorrow’s opportunity and trust between providers and users. The last set regrouped eight socio-demographic questions. Gender, age, education level, and income were used as control variables in the research model for their importance in determining technology usage (Venkatesh et al., 2003).

The response format was standardized using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (5). The questionnaire was then translated to Arabic. Prior to the study, a pilot study was conducted with 10 persons. After this test, the formulation of few questions was modified for the ease of understanding by participants.

Data analysis and Results

Data analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics 23.0.0 for Windows and AMOS 24.0.0. In the descriptive analysis, continuous variables were processed by calculating mean and standard deviation; categorical variables by percentages. Pearson’s chi-square test, ANOVA test and Student t-test were used for bivariate analysis, and linear regression for multivariate analysis. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. This study uses Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) to analyze the data. Respondents who never heard about Sharing Economy were screened out.

Exploratory factor analysis

An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) with varimax rotation was employed using SPSS package. The respondents were asked to express the extent to which they agreed with statements representing the dependent variables. We used multiple items to assess each construct to ensure its validity and reliability.

We conducted Harman’s single-factor test using principal component analysis. The first factor accounted for only 25.34 percent of the variance. The items in the data set loaded significantly onto more than one principal component, indicating no single dominant factor (Harman, 1976).

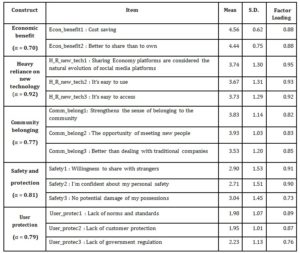

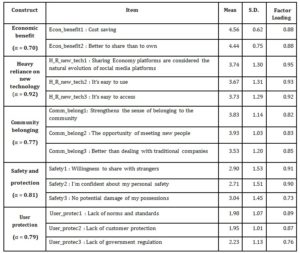

Then we examined the reliability and validity of the constructs. Internal consistency was assessed by following the guidelines from Straub et al. (2004), and Hair et al. (2010). Cronbach’s alpha and the Composite Reliability need to be above 0.70 in order to indicate sufficient reliability. Table 1 shows that all our construct obtained Cronbach’s alpha and Composite Reliability scores above the threshold of 0.70, thus supporting both convergent and discriminant validity of the scales.

Table 1: Summary of key constructs

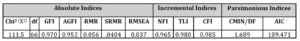

Structural Model Assessment

To answer our research question, a confirmatory factorial analysis (CFA) with AMOS was carried out to apply the widely recognized guidelines of Hair et al., 2010 and Straub et al., 2004, and to verify that both Cronbach’s alpha and Composite Reliability reached an acceptable threshold of 0.70 or higher for every individual construct (on except “No potential damage of my possessions” 0.53, “Lack of government regulation” 0.59, and “Better to share than to own” approximately 0.7).

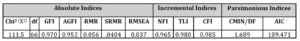

The statistical analysis confirms that the proposed theory fits well our data. The results show that the recommended ‘Absolute fit indices’ and the ‘Incremental fit indices’ provide a fundamental indication of an excellent measurement model. The listed items share only little residual variance and show good fit indexes in our GFI 0.970 AGFI 0.952, CFI 0.985, RMSEA 0.037, PCLOSE 0.965, TLI 0.980 and NFI 0.965 (Bagozzi and Yi 1988; Hu and Bentler 1999).

Figure 1: Research model

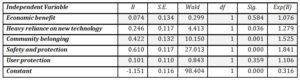

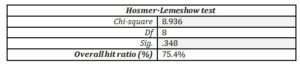

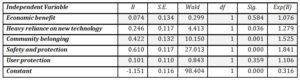

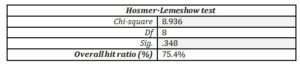

Logistic Regression

To test the suggested hypotheses, we performed a logistic regression. In general, the model fit was satisfactory as demonstrated by the test of Hosmer-Lemeshow (Chi-square greater than .05) and by the hit ratio which shows that 75.4% of the outcomes were correctly predicted by our model in table 3 (Dahlstrom et al., 2009).

The results of the regression highlight the importance of Safety and protection, along with the community belonging and the heavy reliance on new technology in the usage of sharing economy platforms. However, Economic benefit and User protection are not significant in our analysis.

Table 2: The results of the logistic regression

Table 3: The model fit

Discussion

This study and the data analysis contribute to understanding the drivers’ and consumers’ attitudes behind the use of the sharing economy in Lebanon. It is probably one of the first academic papers and analytical studies done in the Middle East area regarding this topic.

Research Implications

The sharing economy creates an enormous amount of wealth (Frenken, & Schor, 2017). Shared between platforms and providers of different services, users are benefiting from these financial and monetary transactions by saving money when it comes to using the services offered by the sharing. Economic factors are very important and are considered as a priority for adopting this economy, the highest mean of all latent variable is for the cost saving (4.56) and then for the preference to share than to own (4.44). More than 60 % of the respondents consider that the Sharing economy opens up extra income opportunities. Our results show that we are in line with the monetary motive which is common for most countries when it comes to using the sharing (Tussyadiah, 2016; Bellotti et al., 2015; Bucher, Fieseler & Lutz, 2016; Böcker & Meelen, 2016). The international economic environment in developing, emerging and developed countries pushed citizens all over the world to search for new sources of revenues; like other populations, Lebanese consumers are in this state of mind. As a touristic country and because they travel a lot, the sharing economy is suitable for the Lebanese. With increasing needs, higher expenditures and consumption, many persons feel compelled to look for additional earnings or saving money through different forms. The excess capacity of goods and services allow individuals to participate in the economic production bypassing the economic formal system. The financial and monetary factors will surely go up in Lebanon and abroad because the sharing economy has many opportunities; trillions of dollars of assets remain underutilized worldwide (Wadhwa, 2018). Under-utilization, idle capacity combined with a slow growth in the economy will expand the sharing economy and many Lebanese are aware that the sharing model will be a huge opportunity. The “shareable goods” as called by Benkler (2004) like homes and cars, offer to their owners with excess capacity and specially homes a good occasion to rent or share them. The three stakeholders of the sharing, the providers, the platforms and the users inject money in the economic system as a whole.

As mentioned earlier, the sharing strategy was practiced in Lebanon since a long time for economic reason but was limited to ride sharing due to the inefficient transportation system and to power generators because of power shortages; the economic impact was limited. Educated Lebanese people with good income are keener to participate in the sharing due to the digital awareness and accessibility to new technologies, while less educated people with low education level suffer from the digital divide. Our results show that 70 % of respondents with bachelor degree and higher are keen to use the sharing economy, 56 % of respondents between 18 and 25 and 66 % aged between 26 and 45 are enthusiasts of this economy. Contrary to what one might think and to international data, Lebanese women and men are equal when using the sharing economy. On the international level, research shows that men, younger people, highly educated and high-income persons tend to be more involved online and consequently they are engaged in this economy (Correa, 2010; Hargittai & Walejko, 2008; Schradie, 2011). The socio-demographic stratification of participation or non-participation in the sharing economy is an important element to understanding this phenomenon. There is some evidence of a ‘participation divide’ and ‘digital inequality’ in the sharing economy (Andreotti et al. 2017).

The new technology and the generalization of the use of Internet decreased the transaction cost and extended the adoption of the sharing beyond the family and the inner circle (Benkler, 2004). As a Mediterranean country where the tradition of hospitality and sharing is well developed among family and friends, our study confirms that the Lebanese people go beyond their relatives and are easily involved in the sharing with strangers. While the roots of the Sharing economy are in the United States, this booming industry reached the Lebanese consumers who participate actively in this new business model. Excess capacity, trust, economic factor and new technology are considered as the key elements of sharing.

The idea of trust is complex and difficult to define. The sharing economy is defined as ‘trust between strangers’ (Botsman & Rogers 2010). Lebanese respondents have no problem trusting strangers. In general, when it comes to renting a room or taking a ride, we noticed that the disposition of trust is the same between men and women, 64% of men respondents and 74% of women trust the sharing plan with a higher confidence rate for women. Because trust is closely related to the use of the platforms and to the reputation and sophisticated rating system adopted, Lebanese people as other citizens give their trust to the intermediary, which means that these platforms are considered as an excellent tool to develop trust. Users are not putting their trust in ‘strangers’ but in the functioning of the rating system as well as the platform and the wider platform ecosystem (Botsman & Rogers 2010); The platforms, thus act as effective information brokers (Hawlitschek, Teubner & Weinhardt 2016). In order to increase trust, the platforms go further than just the reputation or the system of rating; they facilitate the exchange between providers or owners and the users which reduces the anonymous or impersonal dimensions (Celata, Hendrickson & Sanna, 2017). The Lebanese, as users from other countries, are sensitive to the brand of the platforms like Airbnb, Uber,..….because their reputation and their way of doing business are considered as a real guarantee of trust. After covering all the Lebanese territory, we notice that the urban residents have more confidence and trust in the sharing than the rural residents, 70% of residents in Lebanese cities have confidence in this economy against 30% of the inhabitants of the rural areas. We can argue that our findings are in line with the international users because users living in dense urban areas may be more familiar with the act of trusting a stranger (Andreotti et al. 2017).

Since the basis of this new economy is the sharing, the notion of community should be very important even if the economic factors are a priority. Users or providers cannot agree to be involved without being sensitive to sharing with others and particularly with people they have never met. Strengthening the sense of belonging to the community and the opportunity of meeting new people are highly adopted by the respondents, for 67 % consider that sharing reinforces the sense of belonging in the community. They believe also that adopting the sharing economy is better than dealing with traditional companies. Our results are in line with the analysis of Celata, Hendrickson & Sanna, (2017), considering that the narratives of sociality and community are key for the marketing of the sharing platforms as tools offering radical improvements, solidarity and “meaningful” alternatives to the traditional market. The participants in this economy feel a belonging to a community which shares values of trust, adventure, modernity, and new way of dealing with unknown people, openness, and acceptance of differences and of course they consider themselves as adopting the values of the globalization leading to a flat world. Users feel comforted because the platforms help them to select the owners who share the same social criteria (Benkler, 2004). The platforms go beyond the exchange of goods and services, in fact they emphasize the ethical and social behavior by inciting the users to adhere to a common set of social norms and ethical values (Bardhi & Eckhardt, 2012). Their aim is to shift from individual exchange to a logic of community exchange as a whole (Richardson, 2015).

The Sharing economy is a new way of doing business and is considered as a new modality of economic production (Benkler, 2004). This new economy provides familiar service traditionally highly regulated (Sundararajan, 2016). Even if the sharing is self-regulated, the Lebanese users feel sensitive to the lack of norms and standards, customer protection and government regulation. Our results show that 87% of the respondents consider that the sharing economy needs a regulation from the state in order to protect at the same time workers and users. All these issues are largely debated by users and providers of Sharing all over the world. We consider that because of the innovation that this economy introduces in different markets from several fields, it will be problematic to regulate a new invention at the risk of harming this new economic model. The ‘permissionless innovation’ (Thierer, 200) can be a temporary answer to the regulation of this economy considering that experimentation with innovation should be allowed at the beginning of a new business related to a new technological model. As an innovation concept, the regulation of the sharing economy should be approached from an “innovation law perspective” taking into consideration the “experimental” nature of innovation (Ranchordàs. 2015).

Directions for Further Research or limitations

Our study has some limitations. First, whereas a sample size of 673 is acceptable, a larger sample would be preferable in order to cover more users or non-users from different segments of the Lebanese population. Second, we only analyzed four specific sharing economy services, car ride, accommodation sharing and peer-to-peer financing. We cannot limit sharing to these services though even if they are the most important. Other sharing services in other areas could be included in the study, analyzing different sharing economy platforms and the attitudes of users toward the services offered. Third, many small and medium platforms where reputation and trust might not be as important as for big and well-known platforms should be studied.

Conclusion

In this paper, we focused on Airbnb, Uber, Blablacar and Crowdfunding, as important and significant examples of the sharing economy. We worked on five-major hypotheses considered as prominent for users and determinant regarding their adoption of sharing. This new economy is slowly but surely competing with traditional businesses in several areas. The users and suppliers of the sharing all over the world enjoy the benefits this economy is providing them. The results of our study show not only the acceptance but also the enthusiasm of Lebanese respondents for the sharing. Because the tradition of sharing is deeply rooted in people’s minds, sharing in return for a monetary value is easily accepted. Our study has been extended to all regions of the country which gives it a good view of the motivations of all segments of the population. Overall, we hope that other studies will be done in the near future in the Middle East region regarding this topic in order to highlight the Sharing economy with all the benefits and probably the risks it can bring.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

References

- Andreotti, A., Anselmi, G., Eichhorn, T., Hoffmann, C.P. and Micheli, M. (2017), ‘Participation in the Sharing Economy,’ Report from the EU H2020 Research Project Ps2 Share:Participation, Privacy, and Power in the Sharing Economy. [Online], [Retrieved August 31, 2018], https://www.bi.edu/globalassets/forskning/h2020/participation-working-paper.pdf

- Bagozzi, R. P. and Yi, Y. (1988), ‘On the evaluation of structural equation models’, Journal of the academy of marketing science, 16(1), 74-94.

- Bardhi, F. and Eckhardt, G. M. (2012), ‘Access-based consumption: The case of car sharing’, Journal of consumer research, 39(4), 881-898.

- Belk, R. (2014), ‘You are what you can access: Sharing and collaborative consumption online’, Journal of business research, 67(8), 1595-1600.

- Bellotti, V., Ambard, A., Turner, D., Gossmann, C., Demková, K., and Carroll, J. M. (2015), ‘A muddle of models of motivation for using peer-to-peer economy systems’, CHI ’15 Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. 1085-1094.

- Benkler, Y. (2004), ‘Sharing nicely: ‘On shareable goods and the emergence of sharing as a modality of economic production’, Yale LJ, 114, 273-358.

- Böcker, L. and Meelen, T. (2016), ‘Sharing for people, planet or profit? Analysing motivations for intended sharing economy participation’. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 23, 28-39.

- Borel, S., Demailly, D et Massé, D. (2015), ‘L’économie collaborative, entre utopie et big business‘, Esprit, 416 : 9-18.

- Bucher, E., Fieseler, C., and Lutz, C. (2016), ‘What’s mine is yours (for a nominal fee)–Exploring the spectrum of utilitarian to altruistic motives for Internet-mediated sharing’, Computers in Human Behavior, 62, 316-326.

- Celata, F., Hendrickson, C.Y. and Sanna, V. S. (2017), ‘The sharing economy as community marketplace? Trust, reciprocity and belonging in peer-to-peer accommodation platforms’, Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 10(2), 349–363

- Correa, T. (2010), ‘The participation divide among “online experts”: Experience, skills and psychological factors as predictors of college students’ web content creation’, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 16(1), 71-92.

- Dahlstrom, R., Haugland, S. A., Nygaard, A. and Rokkan, A. I. (2009), ‘Governance structures in the hotel industry’, Journal of Business Research, 62(8), 841-847.

- Frenken, K. and Schor, J. (2017). ‘Putting the sharing economy into perspective’, Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 23, 3-10.

- Gerdeman, D. (2018), ‘The Airbnb Effect: Cheaper Rooms for Travelers, Less Revenue for Hotels’, Harvard Business School. [Online], [Retrieved August 02, 2018], https://hbswk.hbs.edu/item/the-airbnb-effect-cheaper-rooms-for-travelers-less-revenue-for-hotels?cid=wk-rss

- Hair, J. F. (2010). Black, WC, Babin, BJ and Anderson, RE (2010). Multivariate data analysis, 7.

- Hargittai, E. and Walejko, G. (2008), ‘The participation divide: Content creation and sharing in the digital age’, Information, Community and Society, 11(2), 239-256.

- Harman, H. H. (1976), Modern factor analysis. University of Chicago press.

- Hawlitschek, F., Teubner, T., Adam, M. T. P., Borchers, N. S., Moehlmann, M. and Weinhardt, C. (2016), ‘Trust in the sharing economy: An experimental framework’.

- Heimans, J. and Timms, H. (2014), ‘Understanding ‘New Power’, Harvard Business Review. [Online], [Retrieved July 31, 2018], https://hbr.org/2014/12/understanding-new-power

- Hosmer Jr, D. W., Lemeshow, S., and Sturdivant, R. X. (2013), Applied logistic regression (Vol. 398). John Wiley & Sons.

- Hu, L. T. and Bentler, P. M. (1999), ‘Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives’, Structural equation modeling: a multidisciplinary journal, 6(1), 1-55.

- Kaplan, A. M. and Haenlein, M. (2010), ‘Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of Social Media’, Business horizons, 53(1), 59-68.

- Lamberton, C. P. and Rose, R. L. (2012), ‘When is ours better than mine? A framework for understanding and altering participation in commercial sharing systems’, Journal of Marketing, 76(4), 109-125.

- Moeller, S. and Wittkowski, K. (2010), ‘The burdens of ownership: reasons for preferring renting’, Managing Service Quality: An International Journal, 20(2), 176-191.

- Karam, L.M. (2016), ‘The Role of User Experience Design in Shared Economy‘, ApiumTech. [Online], [Retrieved June 16, 2018], https://apiumtech.com/blog/user-experience-design-shared-economy/

- Cohen, M. and Sundararajan, A. (2015), ‘Self-regulation and innovation in the peer-to-peer sharing economy’, Chi. L. Rev. Dialogue, 82, 116.

- O’Regan, M. (2013), ’11 Couchsurfing through the Lens of Agential Realism: Intra-Active Construction s of Identity and Challenging the Subject–Object Dualism’, The Host Gaze in Global Tourism, 161.

- Oates, G. (2015), ‘Airbnb’s ambition to be a superbrand that defines a generation’, Skift. [Online], [Retrieved June 16, 2018], http://skift.com/2015/11/17/airbnbwants- to-be-the-superbrand-that-defines-thisgeneration/

- Ranchordás, S. (2015), ‘Innovation Experimentalism in the Age of the Sharing Economy’, Lewis & Clark Law Review. [Online], [Retrieved August 16, 2018], https://law.lclark.edu/live/files/21702-lcb194art1ranchordaspdf

- Richardson, L. (2015), ‘Performing the sharing economy’, Geoforum, 67, 121-129.

- Ronzhyn, A. (2013), ‘Online identity: constructing interpersonal trust and openness through participating in hospitality social networks’. Journal of Education Culture and Society, (1).

- Sacks, D. (2011), ‘The sharing economy’, Fast company, 155(1), 88-131.

- Schradie, J. (2011). ‘The digital production gap: The digital divide and Web 2.0 collide’, Poetics, 39(2), 145-168.

- Straub, D., Boudreau, M. C. and Gefen, D. (2004). ‘Validation guidelines for IS positivist research’, Communications of the Association for Information systems, 13(1), 24.

- Sundararajan, A. (2016) The Sharing Economy: The End of Employment and the Rise of Crowd-Based Capitalism. Mit Press.

- Thierer, A. (2016) Permissionless Innovation: The Continuing Case for Comprehensive Technological Freedom. Mercatus Center at George Mason University.

- Tussyadiah, I. P. (2016). ‘Factors of satisfaction and intention to use peer-to-peer accommodation’, International Journal of Hospitality Management, 55, 70-80.

- Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B.and Davis, F. D. (2003). ‘User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view’, MIS quarterly, 425-478.

- Wadhwa, T. (2018), ‘Why The Sharing Economy Still Hasn’t Reached Its Potential’, Forbes. [Online], [Retrieved August 24, 2018], https://www.forbes.com/sites/tarunwadhwa/2018/07/25/five-ways-to-scale-up-the-global-sharing-economy/#7f14516f2ec5

- Wallenstein, J and Shelat, U. (2017), ‘Hoping Aboard the Sharing Economy’, BCG (Boston Consulting Group) [Online], [Retrieved June 24, 2018], http://image-src.bcg.com/Images/BCG-Hopping-Aboard-the-Sharing-Economy-Aug-2017_tcm9-168558.pdf