Introduction

Based on the high-ceilinged unemployment rate in Nigeria, self employment and small enterprise initiatives are presently one of the country’s national agenda, in the expectation that they will provide unconventional means of profitable engagement. The contest for this is not just only to deal with the already sizeable unemployed graduates, but also of creating a space for the new entrants into the labour force. Crucial to this situation is the fact that the training and education which students of higher institutions of learning receive has not been fully successful in equipping them with desirable skills and competencies required for job creation and self employment (Madumere-obike, 2006, Amaewhule, 2007 and Nwangwu, 2007). The realization of this critical fact lie behind the directive of the Federal Government to all tertiary education regulatory agencies to establish necessary mechanisms for the introduction, development and sustenance of entrepreneurial culture among Nigerian youths and since the education offered by a university mostly influences the career selection of students, universities can be seen as potential sources of future entrepreneurs.

Entrepreneurship is a contemporary concept and is at present recognized as an emerging field of interest globally; it has captured the attention of scholars and policy makers in the last decades. The main rationale of this concern is the growing need for entrepreneurs who can accelerate economic development through generating new ideas and converting them into profitable ventures. Entrepreneurial activities are not only the incubators of technological innovation; they provide employment opportunity and increase competitiveness also (Zahra, 1999). Since the support of entrepreneurship is crucial to stimulate growth in “a growth-conscious economy. In such a learning process, both policy makers and scholars should focus on the question of why some people opt for an entrepreneurial career and others do not.

There has been growing interest in undertaking and increasing actions to promote and support the idea of entrepreneurship as an attractive alternative to wage employment among students around the globe. Despite these efforts, Hisrich and Peters (2002) stated that many students do not consider entrepreneurship as a career and that very few will start a business immediately after graduation .Given the importance of new business start-ups to the economy; this poses a serious problem to the society. The role of students in promoting entrepreneurship remains largely unstudied. Hence, this study aims to fill the gap by investigating the entrepreneurial intention of university students, particularly in the light of some contextual factors like entrepreneurial education access and informal networks of family and friends that may aid business start up.

Also, Past studies has shown that some of the factors responsible for this lack of consideration includes but are not limited to the following: fear of business failure, inaccessibility to start up capital, inadequate infrastructure, lack of enabling environment to mention a few. The effect of these factors on entrepreneurial intention of university students is worth investigating. Lastly, Gorman, Hanlon and King (1997) reviewed series of the literature in entrepreneurship education confirming that preliminary evidence suggests entrepreneurial attributes can be influenced through entrepreneurship education however stated that a stronger empirical focus was required in future research.

Specifically, there is a strong global drive towards encouraging students to pursue entrepreneurship, yet there is much less research on graduate entrepreneurship compared to the existence of a large body of research about entrepreneurship in general (Nabi and Holden 2008). A major source of concern has been the failure to see relatively high levels of apparent intent to start up amongst students (Ward and Wong, 2004, Wu and Wu 2008), and it remains a crucial research question.

Therefore, investigating what factors determine the entrepreneurial intent is a crucial issue in entrepreneurship research. A central question that arose was what factors determined entrepreneurial intent among university students. The objective of this paper is to examine the degree of relationship between entrepreneurial intention of university students and;

Perceived educational support informal network of the students

Literature Review

Conceptual Framework

Concept of Entrepreneurship and its Significance

Thomas & Norman (2008) found that an entrepreneur is one who creates a new business in the face of risk and uncertainty for the purpose of achieving profit and growth by identifying significant opportunities and assembling the necessary resources to capitalize on them. Johnson (2001) described that today the entrepreneur is an innovator or developer who recognizes and seizes opportunities, converts those opportunities into workable or marketable ideas, adds value through time, effort, money or skills, assumes the risks of the competitive marketplace to implement these ideas and realizes the rewards from these efforts.

According to Duygulu (2008) the term “entrepreneur” has often been applied to the founder of a new business, or a person “who started a new business where was there was none before”. Entrepreneurship can be found in the literature describing business processes. Boxill (2003) described the term entrepreneurship comes from the French verb ‘entreprendeur’ and the German word ‘unternehmen’, both of which literally means ‘undertake’. Thus, the entrepreneur is an undertaker someone who undertakes to make things happen, and does. As a generic term, entrepreneurship has been used in a variety of contexts and it covers a broad range of interchangeable meanings and situations.

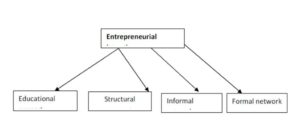

Contextual influences are broadly defined as those factors which pertain to one’s environment or an individual’s interplay with the external environment. It is an extended range of cultural, social, economical, political and technological factors that surrounds a person. According to Bird (1988), intentionality can be defined as a state of mind directing a person’s attention, experience and action towards a specific goal or a path to achieve something. It can also be said to be a state of mind when people wish to create new firm or a new value driver inside an existing organization. In this research work, entrepreneurial intention was narrowed down to the intention to start up a firm or be self-employed.

Also network consists of a series of formal and informal ties between the central actor and other actors in a circle of acquaintances and represents channels through which entrepreneurs get access to the necessary resources for business start-up, growth and success (Kristiansen, 2003). The informal networks consist of all the direct, face-to-face contacts the entrepreneur has including friends, family, close business associates, former teachers and all possible information channels between individuals, a personal network of relationships or alliances, which entrepreneurs develop between them and others in their society and formal network refers to banks, entrepreneurial consulting agencies, law firms, insurance companies, cooperatives, trade association and society of graduated students. Consultants and insurance companies

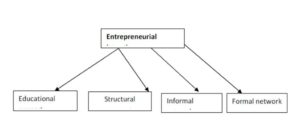

Figure 1: Conceptual Framework of the Effect of Contextual Factors on Entrepreneurial Intention

The Role of Education in Entrepreneurial Intentions

The first dimension of the model is educational support. It is obvious that professional education in universities is an efficient way of obtaining necessary knowledge about entrepreneurship. Therefore, academic institutions might have critical roles in the encouragement of young people to choose an entrepreneurial career. However, they are sometimes accused of being too academic and encouraging entrepreneurship insufficiently (Gibb 2003; Gibb 1996; Gibb, 1993). In order to overcome this insufficiency, most universities have offered entrepreneurship courses or programs at the undergraduate and graduate levels. In the literature, some studies analyse how these entrepreneurial interests of universities affect entrepreneurial inclination of students. The study of Gorman, Hanlon and King (1997) showed that entrepreneurial attributes can be positively influenced by educational programmes. In their study, Kolvereid and Moen (1997) also indicated a link between education in entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial behavior. Similarly, the study of Galloway and Brown (2002) analysed the impact of entrepreneurship electives and found that the return on investment in the entrepreneurship education might be long-term rather than immediate. It is clear that an effective education on entrepreneurship can be a factor to push people towards an entrepreneurial career (Henderson and Robertson, 2000).If a university provides adequate knowledge and inspiration for entrepreneurship, the possibility of choosing an entrepreneurial career might increase among young people. It is obvious that this result confirms the key role of education in the development of entrepreneurial intention.

Entrepreneurial Intention

It has been established that an individual’s intention to become an entrepreneur is the best predictor of his /her actually engaging in entrepreneurship in the future (Delmer & Davidson 2000, Kruger, Reilly and Carsrud, 2000), rather than trait and demographic approaches. Hence research in the field of entrepreneurship is based upon intention models, since entrepreneurial action is actually planned behavior (Krueger et al.2000). Fishbein and Ajzen (1975) operationalised intention as the likelihood to act. Two intention models emerge as dominant in this study and they are Ajzen’s (1987) Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) and Social Cognitive Theory (SCT), originally referred to as Social Learning Theory (Bandura, 1977).

According to Garavan and O’Cinneide (1994), the different stories of successful entrepreneurs stimulate the debate on the famous paradigm of “the entrepreneurs are made or born”. Obviously, it is difficult to ignore the possible impacts of genetics or personality traits. As it is discussed in the next section, the literature provides many studies, which suggest the impacts of these factors. However, in the social sciences, it is a more accurate way to explain every phenomenon with taking into account the interactions of various factors, rather than considering the impact of a single factor. Therefore, even if genetics or personality traits have some impacts on entrepreneurial inclination, it might be better to consider the impact of some contextual factors…”

According to Leonard (1984), owner-managers acknowledge the significance of networks: Networks can be defined ‘as the composite of the relationships in which small firms are embedded, which serve to link or connect small firms to the environments in which they exist and conduct their businesses’ (Shaw and Conway, 2000).

Entrepreneurial Intention Among University Students

Uduak and Aniefiok 2011 in their previous research have shown that there is a significant relationship between entrepreneurship education and career intention. For example, a study by Kolvereid and Moen (1997) has shown that students with a major in entrepreneurship have a higher intention to engage as entrepreneurs and are likely to initiate business. Another study by Noel (2001) confirmed that students who graduated in entrepreneurship reached higher scores in entrepreneurial intention and entrepreneurial self-efficacy than students who graduated in other disciplines. Similarly, Varela and Jimenez (2001) study has shown that there is a correlation between a university’s investment in the promotion of entrepreneurship and the percentage of students becoming entrepreneurs. Additional research by Autio, Keeley, Klofsten, Parker and Hay (2001) found that entrepreneurship education creates a positive image for the entrepreneurs and contributes to the choice of entrepreneurship as a professional alternative by graduates. Wilson, Kickul and Marlino (2007) found that, entrepreneurship education could also increase student’s interest in entrepreneurship as a career.

Theoretical Framework

Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB)

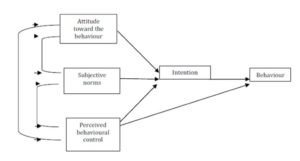

This study is situated within an existing theory-the theory of planned Behaviour- that provided the necessary guide and framework in conducting the study. The Theory of Planned Behaviour (Ajzen, 1991), was derived from the Theory of Reasoned Action (Fishbein and Ajzen, 1975), which states that behavioural intentions are formed by one’s attitude toward that behaviour and one’s subjective norms – (i.e.influence by significant others – e.g. parents, peers, role models). In turn, both attitudes and subjective norm are influenced by evaluations, beliefs, and motivation formed through one’s unique individual environments. Theory of Planned Behaviour, assumes that most human behaviour results from an individual’s intent to perform that behaviour and their ability to make conscious choices and decisions in doing so (volitional control). The Theory of Planned Behaviour (Ajzen, 1991) presents intention dependent upon three factors: (1) the individual’s attitude toward the behaviour (do I want to do it?), (2) subjective norm (do other people want me to do it?), and (3) perceived behavioural control (do I perceive I am able to do it and have the resources to do it?). The third factor, perceived behavioural control is assumed to capture non motivational factors that influence behaviour. Combined, these three factors represent an individual’s actual control over behaviour and are usually found to be accurate predictors of behavioural intentions; in turn intentions are able to account for a substantial proportion of variance in behaviour (Ajzen, 1991).

Source: Ajzen, (1991)

Figure 2 : (TPB) The Theory of Planned Behaviour (Ajzen, 1991)

In the model in Figure 1, intention is shown as the immediate antecedent of behaviour, however in reality we know that not all intentions are ultimately carried out. In some cases an individual may not be able to follow through with the desired behaviour due to external factors, despite having the intention to do so.

Methodology

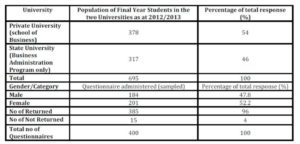

For the purpose of this research, the population of the study comprised of university students. The scope of this study is Lagos and Ogun state in Nigeria due to the large number of universities in the two states. Final year students of a public university in Lagos State and a private university in ogun state were selected as population in which samples were drawn.

The contextual factors considered in the study were limited to both the educational support and informal networks.

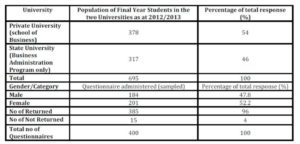

A sample size of four hundred (400) students out of the six hundred and ninety five (695) students population of the selected universities constituted the sample size of the study using Yamane (1974) as sited by Osuala (1982). The reliability test of the instrument was conducted using test re-test reliability approach which yielded r = 0.69 and internal consistency was measured by Cronbach Alpha of 0.885. See the distribution table below

Table: 1 Distribution of respondents and response rate

Source : Field Survey 2012

Data analysis and Hypothesis Testing

Table 2: The Descriptive statistics of Contextual Factors and Entrepreneurial Intention

Source: Field Survey 2012

Hypothesis

Ho1: There is no significant relationship between entrepreneurial intention of university students and perceived educational support

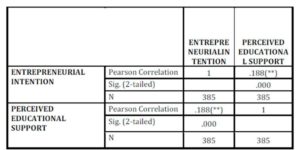

Correlations

** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

The correlation table above shows a Pearson figure of .188 and N figure of 385 as regards significant relationship in respect to perceived educational support and entrepreneurial intention of university students. The significance level below 0.01 implies a statistical confidence of above 99%. This implies that there is a positive and significant relationship between perceived educational support and entrepreneurial intention of university students. Thus, the decision would be to reject the null hypothesis (H0).

Hypothesis 2

Ho2: Informal network have no significant effect on entrepreneurial intention of university students.

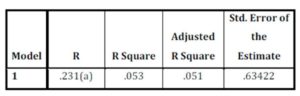

Model Summary

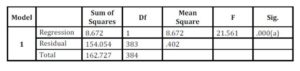

ANOVA(b)

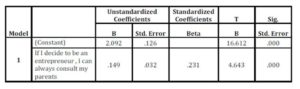

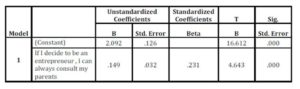

Coefficients(a)

a Predictors: (Constant), INFORMAL NETWORK

b Dependent Variable: ENTREPRENEURIAL INTENTION

The ANOVA table shows the Fcal 21.561 at 0.0001 significance level The coefficient table above shows the simple model that expresses how informal network affects entrepreneurial intention of university students. This means that for every 100% change in ENTREPRENEURIAL INTENTION, informal network contributed 14.9%. Thus, the decision would be to reject the null hypothesis (H0).

Discussion on Findings

The result of hypothesis one which confirms that there is a significant relationship between entrepreneurial intention of university students and perceived educational support agrees with the submission of Uduak and Aniefiok (2011). They concluded in their study that educational support does influence entrepreneurial intention. It can also be related to the study of Noel (2001) with the conclusion that if university provides adequate knowledge and inspiration for entrepreneurship the possibility of choosing an entrepreneurial career might increase among students; thus confirming the key role of education in the development of entrepreneurial intention. Entrepreneurial programmes raise attitudes and behaviour capable of provoking entrepreneurial intention among university students. Similarly the results of the study conducted by Bassey and Olu (2008) reveals that knowledge and skills are major influencing factors in students’ entrepreneurial intentions. Clearly, the university as an institution of learning plays a vital role in determining entrepreneurial inclination and action among students.

The result of the second hypothesis which concludes that informal networks have significant effect on entrepreneurial intention of university students and informal networks can be related to the result of Greve and Salaff (2003) that family is an important factor in the career choice of university students. This outcome is also supported in Raijman (2001) where he examined the role of social networks; in which individuals are embedded in predicting entrepreneurial intent. His results confirmed that having close relatives who are entrepreneurs increased the willingness to be self- employed.

It can be summarized and deduced from this study that following applies to University students in Nigeria:

i. There is a high level of entrepreneurial intentions among university students.

ii. The university as an educational institute has a great impact on a student’s decision to go into self employment.

iii. Informal networks (friends, families, relatives and course mates) play a significant role in influencing a student’s entrepreneurial intentions

Conclusion and Recommendations

In this study, it has been established that contextual factors does have an effect on the entrepreneurial intention of university students in Ogun State. The first factor is the educational support that indicates mainly a supportive university environment shows that if a university provides adequate knowledge and inspiration for entrepreneurship, the possibility of choosing an entrepreneurial career might increase among students. This finding confirms the key role of education in the development of entrepreneurial intention. In the light of current study, it can be said that entrepreneurship can be fostered as a result of the learning process.

The second factor which also emerged very significant is the informal network. Social ties are significant for a person more so a university student. Since people are more integrated into the society; family, relatives, friends and course mates will most likely influence a career selection decision in a young person.

Based on the findings of the study, the following recommendations were made:

Universities

Universities are advised to;

i. Create an entrepreneurship center in the university where creative enterprising ideas can be developed and nurtured; provision of necessary knowledge about entrepreneurship can be made available and development of entrepreneurial skills are encouraged.

ii. A web site should also be created where students can have access to education, consulting and informational services.

iii. Establish entrepreneurship mentoring programmes which will connect new entrepreneur students to experienced entrepreneurs inside and outside the university.

Informal network

Parents, friends and relations should endeavour to give appropriate moral, professional and financial supports to youths with entrepreneurial intentions.

Government

The paper also recommended that government should provide necessary support for quality teaching of entrepreneurship in Nigerian Universities as well as providing enabling environment for entrepreneurial practices.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

References

1. Ajzen, I. (1987). “Attitudes, traits, and actions: Dispositional prediction of behavior in personality and social psychology”, Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Vol. 20, pp.1-63.

Google Scholar

2. Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behaviour. Organisational Behaviour and Human Decision Processes, Vol. 50, pp 179-211.

3. Amaewhule, W. A. (2007). Education, the world of work and the challenge of change: In search of intervention strategies. Inaugural lecture series No. 23; River State University of Science and Technology, Nkpolu Port Harcourt.

4. Autio, E., Keeley, R., Klofsten, M., Parker, G., Hay, M. (2001) Entrepreneurial intent among students in Scandinavia and the USA, Enterprise and Innovation Management Studies.

Publisher – Google Scholar

5. Bandura, A. (1977), “Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change”, Psychological Review, Vol. 84 No. 2, pp. 191-215.

Google Scholar

6. Bassey, U. U. & Olu D. (2008). Tertiary Education and Graduate Self-Employment Potentials in Nigeria. Journal of the World Universities Forum, 1(3), 131 – 42.

7. Baumol, W. J. (1993) Entrepreneurship, Management, and the Structure of Payoffs, Cambridge: The MIT Press.

8. Bird, B. (1988) Implementing entrepreneurial ideas: the case for intention, Academy of Management Review, 13, 3, 442-453.

Publisher – Google Scholar

9. Boxill, I. (2003). Unearthing Black Entrepreneurship in the Caribbean: Exploringthe Culture and MSE sectors. Equal Opportunities International Vol. 22,No 1.

Publisher – Google Scholar

10. Delmar, F. and P. Davidson (2000), Where do they come from? Prevalence and characteristics of nascent entrepreneurs, Entrepreneurship and regional development 12, 1-23.

Publisher – Google Scholar

11. Duygulu, E. (2008). Institutional Profiles and Entrepreneurship Orientation: A case of Turkish Graduate Students, Dokuz Eylul University.

Google Scholar

12. Fishbein, Martin and Icek Ajzen (1975), Beliefs, Attitudes, Intentions and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research, (Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley).

Google Scholar

13. Galloway, L., & Brown, W. (2002). Entrepreneurship education at university: a driver in the creation of high growth firms? Education + Training, Vol. 44 (8/9), 398-405

Google Scholar

14. Garavan, T. N. and O’Cinneide, B. (1994). Entrepreneurship Education and Training Programmes: A Review and Evaluation – Part 1. Journal of European Industrial Training 18(8), 3-12.

Publisher – Google Scholar

15. Gelard P. & Saleh, E. K. (2011). Impact of some contextual factors on entrepreneurial intentions of university students. Journal of Business management, 5(26) 10707 – 10717

16. Gibb, A. A. (1993). The enterprise culture and education: understanding enterprise education and its links with small business, entrepreneurship and wider educational goals. International Small Business Journal, Vol. 6 No. 3, 11-34.

Publisher – Google Scholar

17. Gibb, A. A. (1996). Entrepreneurship and small business management: can we afford to neglect them in the twenty-first century business school? British Academy of Management. Vol. 7, 309- 321.

Publisher – Google Scholar

18. Gibb, A.A. (2002) ‘ In pursuit of a new ‘enterprise’ and ‘entrepreneurship paradigm for learning: creative destruction, new values, new ways of doing things and new combinations of knowledge’ International Journal of Management Reviews Vol.4 No. 3 pp. 213-233

Publisher – Google Scholar

19. Gorman, G., Hanlon, D., and King, W. (1997) Some research perspectives on entrepreneurship education, enterprise education, and education for small business management: A ten year literature review, International Small Business Journal, 15, 3, 56-77.

Publisher – Google Scholar

20. Henderson, R. & Robertson, M. (2000). Who wants to be an entrepreneur? Young adult attitudes to entrepreneurship as a career. Career Development International, Vol. 5 No. 6, 279-87.

Publisher – Google Scholar

21. Hisrich, R. and Peters, M. (2002) Entrepreneurship (5th ed.). McGraw-Hill. NY.

Google Scholar

22. Johnson, D. (2001). What is innovation and entrepreneurship? Lessons for larger organisations. Industrial and Commercial Training, 33, 135-140.

Publisher – Google Scholar

23. Kolvereid, L. & Moen, O. (1997). Entrepreneurship among business graduates: Does a major in

Entrepreneurship make a difference? Journal of European Industrial Training, 21 (4), 154.

Google Scholar

24. Krueger, N., Reilly, M., and Carsrud, A. (2000) Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, 15, 5-6, 411-432.

Publisher – Google Scholar

25. Leonard-Barton, D. (1984) Interpersonal Communication Patterns Among Swedish and Boston-Area Entrepreneurs, Research Policy, 13:2, pp. 101-114.

Publisher – Google Scholar

26. Madumere-Obike, C. U. (2000). Reposition Education for Employment: Implications for educational management. Multidisciplinary Journal of Research Development (MIKJORED); 7(3) 43-52.

27. Nabi, G & Holden, R. (2008). Graduate entrepreneurship: Intentions, education and training. Education and Training, Vol. 50, No. 7, pp 545-551

Publisher – Google Scholar

28. Noel, T.W (2001) “Effects of Entrepreneurial Education on Intent to Open a Business’’ Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research, Babson Conference Proceedings, www.babson.edu/entrep/fer

29. Nwangwu I. O. (2007). Entrepreneurship in education. Concept and constraints. African Journal of Education and Developmental Studies 4(1), 196 – 207.

30. Osuala E.C. (1982). Introduction to Research Methodology. Onitsha: Africa Fep Publishers Limited.

31. Shaw, E. and Conway, S. (2000), ‘Chapter 21 Networking and the Small Firm’, in Carter, S and Jones-Evans, D. eds, Enterprise and Small Business: Principles, Practice and Policy, Essex:Pearson Education, p.p 367-383.

32. Uduak and Aniefiok (2011) Entrepreneurship Education and Career Intentions of Tertiary Education Students in Akwa Ibom and Cross River States, Nigeria- www.ccsenet.org/ies International Education Studies Vol. 4, No. 1; February 2011

Google Scholar

33. Varela, R. & Jimenez, J. E. (2001). The effect of entrepreneurship education in the Universities of Cali. Frontiers of entrepreneurship research, Babson Conference proceedings.

34. Wilson, F., Kickul, J., & Marlino, D. (2007). Gender, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and entrepreneurial career intentions: Implications for entrepreneurship education. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 31(3), 387-406.

Google Scholar

35. Wu, S. and Wu, L. (2008), “The impact of higher education on entrepreneurial intentions of kuniversity students in China”, Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 15 (4) 752- 774

Publisher – Google Scholar

36. Zahra S. (1999) The Changing Rules of Global Competitiveness in the 21st century: Academy of

Management Executive, 1999. – No.13. – pp. 36 – 42.

Google Scholar