Introduction

The relationship between personality and career success has stimulated a great deal of speculation. Career success is a way for individuals to fulfil their need for achievement and power because it improves people’s quantity and quality of life. Research on career success not only benefits individuals but also organizations because employee personal success will eventually translate into organizational success (Judge, Higgin, Thoresen, & Barricj, 1999). Scholars note that employees may remain committed productive members of an organization as long as they believe that the organization helps them achieve positive career experiences, or intrinsic career success (Gaertner & Nollen, 1989; Igbaria, 1991; Lee & Maurer, 1997). Career paths have become increasingly ambiguous and individuals must take responsibility for managing their own careers as organizations face more complex and challenging business landscapes (Hall, 1996; Hall & Mirvis, 1995).

Career choices reflect a person’s self-perception regarding his or her abilities, values and personality along with assessments of how these individual aspects fit the particular occupation. Researchers have only recently begun to understand the role of personality in career success (e.g., Howard & Bary, 1994; Judge, Higgins, Thoresen & Barrick, 1999; Seibert, Crant, & Kraimer, 1999). Thus this comprises a serious gap in literature because personality is found to be important in many other related domains of organizational behaviour. Judge et al. (1999) summarized a large set of previously collected personality ratings based on a comprehensive personality framework (the Five-Factor model of personality; Goldberg, 1990) and examined their relationship to career success. Following the suggestion by Osipow and Fitzgerald (1996), examining the interaction between personality and career outcomes is intuitively appealing to researchers. Given the dearth of studies on career success within the Malaysian context, it seems reasonable to extend previous research on careers by examining the unique contribution of the Big Five dimensions of personality to career success among Malaysian managers.

In shifting to a knowledge-based economy, Malaysia’s main responsibility lays in the development of its human capital (Halimah, 2004). Managers in public and service sectors are experiencing substantial transformation in organizations via organizational as well as career changes affecting long-term relationship and psychological contract between organizations and employees. This study focused on the Malaysian hotel industry due to several reasons. First, the Malaysian hotel industry has undergone drastic changes during the last five years, with regard to its external environment, largely due to the greater extent of volatility in the environment and the increasing level of uncertainties in the world’s economy. To date, the services sector, of which hotel is one of its component, has been a major player in the growth of the Malaysian economy, contributing approximately 50 percent to the nation’s real GDP. Second, the hotel industry is one of the most promising service-oriented industries in Malaysia. There has been numerous contributions of the hotel sector to the national economy including : providing employment opportunities, providing alternatives and added income for rural population, supporting the growth of secondary activities such as material and equipment suppliers, and complementing the expansion of both domestic and inbound tourism. It is worth considering how personality traits might have an effect on the careers of hotel managers since that personality can lead to numerous work-relevant outcomes.

Most companies are interested in determining which employees are likely to progress within their organization since succession planning has become a common practice in many firms (Garman & Glawe, 2004). Given the importance of career success and the significant role played by the hotel industry in Malaysia, investigating the relationship between personality traits and hotel managers’ career success is considered worthy.

Literature Review

Career Success

In the early 20th century, career has been synonymously referred to as occupation. In the 1950s and 1960s, career was viewed by relating occupation to individual’s life. Super, Tiedman and Borrow (1961) defines career as the sequence of occupations, jobs and positions in the life of an individual. Leisure was later suggested by McDaniels (1965) to be integrated to give career definition a broader perspective. In the 1970s and 1980s, the concept of career was continuously defined in a broader perspective. For instance, the National Vocational Guidance Association (NVGA) in 1973 defined career as a ‘time-extended working out of a purposeful life pattern through work undertaken by the individual’. Career started to be viewed in a broader sense that incorporates almost all life activities, across individual’s lifespan, and was no longer seen occupational in manner.

The evolution of career theory has thus posed a similar effect on the definitions of career success. When the construct of career success was introduced in the year 1937 by Hughes and the Chicago School of Sociology during the 1930s, early psychological career development theories focused on more active role of organizations in determining an individual’s career success. Career success was defined rather objectively by focusing on the more visible aspects of an individual’s career circumstances, such as profession, work role, salary, type of work, career progression and status or prestige associated with a position, level or hierarchy (Van Maanen, 1977). It is being measured in terms of society’s evaluation of achievement with reference to extrinsic measures such as salary, managerial level and number of promotions (Melamed, 1996; Whitely, Dougherty and Dreher, 1994).

In the early 1970s, the definition of career success began to incorporate the aspect of subjectivity. Judge et al. (1995) defined career success as the positive psychological outcomes or achievements one has accumulated as a result of experiences over the span of a working life. Lau and Shaffer (1999) viewed career success as a means to fulfil a person’s needs and desires through achievements, accomplishment and power acquisition (Lau & Shaffer, 1999). Seibert, Kraimer and Liden (2001) defined career success as the accumulated positive work and psychological outcomes resulting from one’s work experiences. Traditionally, research in career success was concerned with measuring success based on a person’s progression in a profession, hierarchical level in an organization and/or promotions (Kirchmeyer, 1998). More recently, researchers (Judge et al. 1995; Melamed, 1996; Nabi, 1999; Sagas & Cunningham, 2004) have begun to measure career success from both an extrinsic (objective) and intrinsic (subjective) perspective which links individuals and organizations for which they work.

Extrinsic success is relatively objective and observable, and typically consists of highly visible outcomes such as pay and ascendancy (Jaskolka, Beyer, & Trice, 1985). Research confirms the idea that extrinsic and intrinsic career success can be assessed as relatively independent outcomes since they are only moderately correlated (Bray & Howard, 1980; Judge & Bretz, 1994). Judge et al. (1995) defined extrinsic success in terms of salary and number of promotions. The objective career is publicly accessible and is concerned with social role and official position. Writers who see career success from this perspective view it in structural terms (Wilensky, 1961) and emphasize people’s propensity to organize status differences (Nicholson, 1998). Objective career success reflects shared social understanding rather than distinctive individual understanding.

Conversely, intrinsic success is defined as an individual’s subjective reactions to his or her own career, and is most commonly operationalized as career or job satisfaction (Gattiker & Larwood, 1988; Judge et al., 1995).In terms of intrinsic success, it appears that job satisfaction is the most relevant aspect. Individuals who are dissatisfied with many aspects of their current jobs are unlikely to consider their careers, at least at present, particularly successful. Thus, consistent with previous career success research (Judge & Bretz, 1994), job satisfaction is considered the most relevant aspect of career success. Subjective career success can be measured in terms of individual’s feelings of success with reference to intrinsic indices such as perceptions of career accomplishments and future prospects (Aryee et al., 1994). It is now believed that an individual who is objectively successful by being highly-paid, promoted or empowered with supervision authority may still be unhappy. This is due to the fact that individual’s perspective on success is actually affected by life situations such as family commitments, dual income and health (Gunz and Heslin, 2005).

Personality Traits

A person’s personal characteristics mainly describe and predict his/her behaviour, not behavioural changes or development. The systemic classification of personal characteristics suggested by McDougall (1932) asserts that personality consists of five factors: intellect, character, temperament, disposition and temper. Furthermore, Cattell (1943) proposes a more complicated classification with 16 main factors and 8 secondary factors. In their analysis of Cattell’s approach, Tupes and Christal (1961) find that five factors (extroversion, neuroticism [emotional stability], agreeableness, conscientiousness, and culture) explain the classification, and their proposed factors match McDougall’s views. The meta-analysis by Barrick and Mount (1991) confirmed the existence of five dimensions that most researchers continue to use today: neuroticism (emotional stability), extroversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness.

Judge et al. (1999) summarized a large set of previously collected personality ratings according to a comprehensive personality framework (the Five-Factor model of personality; Goldberg, 1990) and examined their relationship to extrinsic career success (a composite measure of salary and occupational status) and the proxy for intrinsic career success is job satisfaction. Personality has been conceptualized from a variety of theoretical perspectives, and at various levels of abstraction or breadth (John, Hampson, & Goldberg, 1991; McAdams, 1995). Each of these levels has made unique contributions to our understanding of individual differences in behaviour and experience. However, the number of personality traits, and scales designed to measure them, escalated with no end in sight (Goldberg, 1971).

The Big Five Inventory (BFI) is a 44-item personality instrument designed to measure the big five personality factors: extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness to experience. The items are not equally spread across these factors. Extraversion and neuroticism are indicated by eight items each, agreeableness and conscientiousness are indicated by nine items each and openness to experience is measured with ten items. Given the high degree of consensus regarding the structure of the personality domain that has emerged among personality researchers during the past decades (Mount & Barrick, 1995), it seems reasonable to extend previous research on careers by examining the unique contribution of the Big Five dimensions of personality to career success. Indeed, in their review of personality and vocational behaviour research, Tokar et al. (1998) highlighted the need to examine personality in relation to career progression and encouraged the use of the Big Five personality factor structure in this endeavour.

Neuroticism indicates adjustment versus emotional stability. Individuals who are rated high on neuroticism are characterized by high levels of anxiety, hostility, depression, and self-consciousness. Neuroticism is the most pervasive trait across personality measures and it is prominent in nearly every measure of personality. Neuroticism leads to at least two related tendencies; one dealing with anxiety (instability and stress proneness), the other addressing one’s well being (personal insecurity and depression). Thus, neuroticism refers generally to a lack of positive psychological adjustment and emotional stability.

Typically, extraversion is thought to consist of sociability. High levels of extraversion indicate sociability, warmth, assertiveness and activity; whereas individuals low on extraversion may be described as reserved, sober, aloof, task-oriented and introverted. However, extraversion is a broad construct that also includes other factors. According toWatson and Clark (1997), extraverts are more sociable, but are also described as being more active and impulsive, less dysphoric, and as less introspective and self-preoccupied than introverts (p. 769). Thus, extraverts tend to be socially oriented (outgoing and gregarious), but also are dominant, ambitious and active (adventuresome and assertive). Extraversion is related to the experience of positive emotions, and extraverts are more likely to take on leadership roles and to have a greater number of close friends (Watson & Clark, 1997).

Openness to experience is defined in terms of curiosity and the tendency for seeking and appreciating new experiences and novel ideas (Seibert & Kraimer 2001). Openness to experience is characterized by intellectance (philosophical and intellectual) and unconventionality (imaginative, autonomous, and nonconforming). Individuals who score low on openness are characterized as conventional, inartistic and narrow in interests.

Agreeableness is one’s interpersonal orientation, ranging from soft-hearted, good-natured, trusting and gullible at one extreme to cynical, rude, suspicious and manipulative at the other (Seibert & Kraimer, 2001). Agreeable persons are cooperative (trusting of others and caring) as well as likeable (good natured, cheerful and gentle).

Finally, conscientiousness indicates an individual’s degree of organization, persistence and motivation in goal-directed behaviour. Achievement-orientation and dependability or conformity have been found to be primary facets of conscientiousness (Hogan & Ones, 1997).

Conscientiousness, which has emerged as the Big Five construct most consistently related to performance across jobs (Barrick & Mount, 1991; Salgado, 1997), is manifested in three related facets :achievement-orientation (hardworking and persistent), dependability (responsible and careful) and orderliness (planful and organized). Thus, conscientiousness is related to an individual’s degree of self-control as well as the need for achievement, order and persistence (Costa, McCrae, & Dye, 1991). As one examines these hallmarks of conscientiousness, it is not surprising that the construct is a valid predictor of success at work.

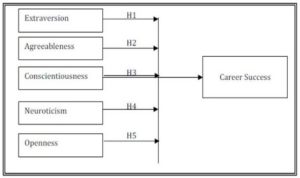

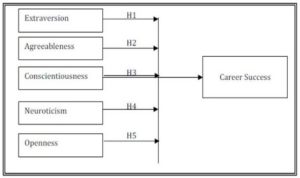

Drawing from the above mentioned literature, this study postulates that personality traits influence career success. Figure 1 below shows the proposed research framework.

Research Framework

Figure 1: Framework for Personality Traits towards Career Success

Hypotheses

Traits used to describe extraversion include being sociable, outgoing, assertive, talkative and active (Barrick & Mount, 1991). Individuals possessing a high level of extraversion are predisposed to have both positive affect and cognitions. They are optimistic about the future, less susceptible to distraction and less affected by competition than introverts (Eysenck, 1981). Extraversion is characterized by ambition reflecting individual differences in mastery seeking and perseverance (Clark & Watson, 1991).

Hypothesis 1: Extraversion is positively related to career success.

Agreeableness traits are similar to being imperturbable, a characteristic of those who are high in agreeableness (McCrae & Costa, 1987). Characteristics of individuals who are low in agreeableness, such as being competitive and interested in proving their abilities, are traits that may parallel those of a performance approach towards their career success. Organ and Lingl (1995), Judge, Heller and Mount (2002) and Azalea, Omar and Mastor (2009) concluded that agreeableness is modestly positively correlated with career success. Therefore, this study hypothesed that:

Hypothesis 2: Agreeableness is negatively related to career success.

Conscientiousness is a general personality trait commonly characterized as careful, thorough, responsible, organized, self-disciplined and scrupulous at one end, to irresponsible, disorganized, undisciplined and unscrupulous at the other end (McCrae & Costa, 1987). Conscientiousness also incorporates other characteristics such as being hardworking, persevering and achievement-oriented (Barrick & Mount, 1991). According to Barrick, Mount, and Strauss (1993), conscientiousness may be the most important trait-motivation variable in the work domain. Meta- analytic evidence has found conscientiousness to be one of the best predictors of job performance (Barrick & Mount, 1991).

Hypothesis 3: Conscientiousness is positively related to extrinsic career success.

Common traits associated with neuroticism include being anxious, worried, depressed, angry and insecure (McCrae & Costa, 1987) Furthermore, Elliot and Thrash (2002) found that neuroticism is related to career success. Theory and evidence suggest a negative relationship between neuroticism and job satisfaction; the opposite is true with respect to extraversion.

Hypothesis 4: Neuroticism is negatively related to career success.

Characteristics used to describe openness to experience include imaginative, sensitive, intellectual, and curious at one end of the continuum, and insensitive, narrow and simple at the other end (McCrae & Costa, 1987). Individuals with a high level of openness to experience appreciate variety and intellectual stimulation and are better at grasping new ideas (Costa & McCrae, 1988). These individuals generally have more favourable attitudes toward learning experiences (Barrick & Mount, 1991).

Hypothesis 5: Openness to experience is positively related to career success.

Methodology

The research sample comprised of managers working in hotels located in two northern states in Malaysia, which comprised of Penang and Kedah. Respondents comprised of managers working from various managerial grades starting from the lower management to general manager of each department. Specifically, data were collected from a sample of male and female managers working in hotels of Penang and Pulau Langkawi, Kedah. This is because Penang and Pulau Langkawi, Kedah have flourished tremendously over the past decade as tourism destinations. Respondents are identified using purposive sampling.

Respondents were asked to respond to self-administered questionnaire comprising of three sections: subjective career success, personality traits, and socio-demographic details. In this study, subjective career success reflects a manager’s perceptions of his/her career success, which was measured using 8 items taken and modified from Greenhaus et al.’s (1990) and Turban and Dougherty’s (1994) measures. This scale has been reported to have good internal reliabilities of .83 in previous studies. Three of the items were negatively-worded and had to be reverse-coded to prevent common response bias. Respondents were asked to indicate on a 5-point scale of (1) never to (5) always, the extent of their agreement or disagreement on how each of the given statements relates to them. A sample item includes, “I am satisfied with the progress I have made toward meeting my overall career goals.” An average of all the items would be computed to arrive at the career satisfaction score. A higher score would suggest higher level of career satisfaction.

Personality traits were measured using a 44-items Big Five Inventory scale (BFI; John et al., 1991; John & Srivastava, 1999) covering five broad traits – Neuroticism, Extraversion, Openness, Agreeableness, and Conscientiousness. Respondents were asked to indicate on a 5-point scale of (1) never to (5) always, the extent of agreement or disagreement on how each of the given statements relate to them.

Socio-demographic variables such as age, gender, marital status, educational attainment and work as well as organizational tenure were also collected and analyzed.

Results

Response and Profile of Respondents

Out of 200 questionnaires distributed, 90 questionnaires were received and only 83 were usable for data analysis, representing a response rate of 41.5%. The sample profile of the respondents is shown in Table 1.

As depicted in Table 1, 53% of the respondents were males whilst the remaining 47% were females. In terms of age, 48.1% of the respondents were in the 31 to 40 years age group. In terms of education, 46.9% of the respondents were diploma and degree holders. About 35% of the sample have more than 10 years of work experience.

Table 1: Profile of the Respondents

Descriptive Statistics and Cronbach’s Alpha

Cronbach’s alpha is an index of reliability associated with the variation accounted for by the true score of the “underlying construct.” The “underlying construct” is the hypothetical variable that is being measured (Sekaran, 1999). Alpha coefficient ranges in value from 0 to 1 and may be used to describe the reliability of factors extracted from dichotomous and/or multi-point formatted questionnaires or scales. The higher the score, the more reliable the scale is.

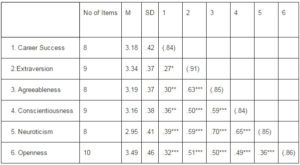

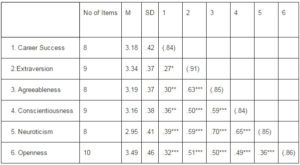

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics, Cronbach’s Alpha, and zero-order correlation between career success and dimensions of personality.

Table 2: Descriptive Statistics, Cronbach’s Alpha and Zero-order Correlation of Career Success

Note. N=83; *p<.05; **p<.01; ***p<.001; Diagonal entries indicate Cronbach’s alpha coefficients.

As shown in Table 2, the highest Cronbach’s value is reported for extraversion at .91, followed by Openess at .86. As for the other dimensions, the Cronbach’s value is between .84 to .85. Since the Cronbach alpha for all the six items are above .8, the internal consistency reliability of these measures can be considered to be good (Sekaran, 1999).

Test of Hypotheses

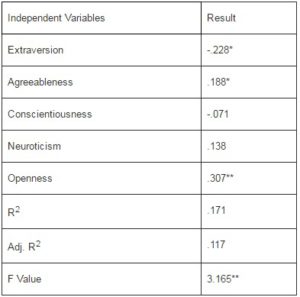

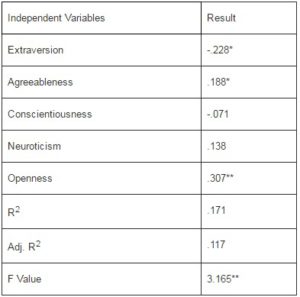

The hypotheses were tested using the multiple regression analysis (Baron & Kenny, 1986). The results of the regression analysis is depicted in Table 3.

Table 3: Regression Analysis Results

Note. N = 83, *p<0.1, **p<.0.05, ***p<.001

Note. N = 83, *p<0.1, **p<.0.05, ***p<.001

As shown in Table 3, when all personality traits were entered into the regression analysis, the coefficient of determination (R2) is 0.171, indicating that 17.1% of career satisfaction is explained by the managers’ personality traits. From the five personality traits, extraversion (ß = -.228), agreeableness (ß = .188) and openness (ß = .307) were found to be significantly related to career success. Unlike agreeableness and openness, which are positively related to career satisfaction, extraversion has a negative effect on career satisfaction. On the other hand, the other two remaining personality traits (conscientiousness and neuroticism) were found to be unrelated to career satisfaction. In summary, results from this study were divided. Extraversion which normally has a positive relationship with career satisfaction, as mentioned in many previous literatures, was found to be negatively related to career satisfaction.

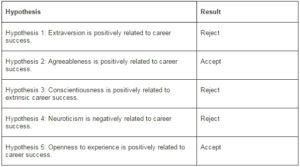

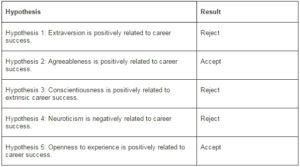

Table 4 shows the summary of hypotheses.

Summary of Hypotheses

Table 4 – Summary of Hypotheses

Results and Discussion

Generally, managers understand that to enter the global arena and to be successful in their careers, they need to create a working environment that will match the personality, needs and motivations of their employees so that their employees will be satisfied and willing to walk the extra mile for the company’s mission rather than their own self interest. It is because, once the employees are comfortable at their working place, then only they are willing to involved with knowledge sharing which will ultimately lead to a productive work place (Chen, Meindl & Hui, 2000). Unfortunately, it is not an easy task to encourage the sharing principle. In the same article, the authors (Chen, Meindl, and Hui (2000) mention that knowledge locked in the human mind requires a different approach to not only unlock it but also to stimulate its growth.

A study by Judge et al. (1999) reported that personality appears to be most relevant to career success. Judge et al. (1999) noted that extraversion has a positive relationship with career success. However, in this study, extraversion was found to be negatively related to career satisfaction. This contradictory finding may be due to the background of the sampled managers. Given that the majority of the respondents were relatively young, (between the ages of 31 – 40 years) and have more than 10 years of working experience, they fall under the category of Generation X, i.e. workforce with different work ethics and culture. According to Shultz (2000), this generation entered the workforce expecting to be sole proprietors based on their own skills and abilities in performing tasks rather than wanting to use their personality to achieve career satisfaction.

Another interesting finding is the lack of relationship between two personality traits (conscientiousness and neuroticism) with career success. Despite evidences highlighting these two dimensions as significant contributors to career success, this study records a non-significant relationship. Barrack and Mount (1991) and McCrae and Costa (1991) were among the researchers who concluded that conscientiousness has a close link with one’s career and life success. Howard and Bray (1994) and Jones and Whitimore (1995) also arrived at the same conclusion albeit using a different population. In previous studies, neuroticism has been discovered to have a negative relationship with career success. However, in the present study, these two dimensions were not significant predictors of career success. This contradictory result may be rationalized from the perspective of the demographic profile of our sampled managers.

In addition, our finding on the effect of agreeableness on career success is consistent with those of prior studies. Agreeableness refers to a tendency to being sympathetic and eager to help others. The nature of these traits such as trust, straightforwardness, altruism, compliance, modest and tender-mindedness are actually an asset for those working in the hotel industry. When we match these facets with the job description of the managers, we can easily understand why the relationship is positive and significant toward career success among the hotel managers. Since they are in the service industry, facing the customer is part of their routine job.

Similarly, openness to experience has been argued to be positively related to career success. Our findings concurred with those of previous researchers. For instance, a study by Gunkel and Schlaegel, Langella and Peluchette (2010) in Germany revealed that openness to experience have a positive and significant relationship with career success.

As with any study, this study is not free from limitations. Our respondents were only confined to hotel managers located in two states in northern Malaysia. Hence, our findings may not be generalized to other occupational groups and other industries.

In conclusion, the hotel industry has become very competitive and employers must realize that their competitive advantage is closely tied to their human resources. Apart from investing in marketing and promotion, management has to ensure that their human capital is performing at their level best. Whilst career success might be the objective of the employees, career success will ultimately lead to higher quality human capital resulting in greater productivity. Drawing from the results, it is best for employing organizations to understand their employees via their personalities.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

References

Abdul Wahat, N. W. (2011). “Towards Developing a Theoretical Framework on Career Success of People with Disabilities,” Asian Social Science, Vol 7, No 3; March 2011.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Aryee, S., Chay, Y. W. & Tan. H. H (1994). “An Examination of Antecedents of Subjective Career Success among a Managerial Sample in Singapore,” Human Relations, 4(5), 487-509.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Awang, K. W., Ishak, N. K. , Radzi, S. M. & Taha, A. Z. (2008). “Environmental Variables and Performances: Evidence from the Hotel Industry in Malaysia,” Int. Journal of Economics and Management 2 (1): 59-79

Publisher – Google Scholar

Azalea, A., Omar, F. & Mastor, K. A. (2009). “The Role of Individual Differences in Job Satisfaction among Indonesians and Malaysians,” European Journal of Social Sciences 9, 496 – 511.

Publisher

Barrick, M. R. & Mount, M. K. (1991). “The Big Five Personality Dimensions and Job Performance: a Meta-Analysis,” Personnel Psychology, 44, 1 – 26.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Barrick, M. R., Mount, M. K. & Strauss, J. P. (1993). “Conscientiousness and Performance of Sales Representatives: Test of the Mediation Effects of Goal Setting,” Journal of Applied Psychology, 78, 715–722.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Boudreau, J. W., Boswell, W. R. & Judge, T. A. (2001). “Effects of Personality in Executive Career Success in the United States and Europe,” Journal of Vocational Behavior, 58, 53-81.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Bretz, Jr. R. D. & Judge, T. A. (1994). “Person-Organisation Fit and the Theory of Work Adjustment: Implications for Satisfaction, Tenure, and Career Success,” Journal of Vocational Behaviour, 58, 53-81.

Publisher

Chenevert, D. & Tremblay, M. (2002). “Managerial Career Success in Canadian Organizations; is Gender a Determinant?,” The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 13(6), 920-941

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Doverspike, D. , Taylor, M. A., Shultz, K. S. & McKay, P. F. (2000). “Responding to the Challenge of a Changing Workforce : Recruiting Non-Traditional Demographic Groups,” Academia.Edu.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Elliot, A. J., & Church, M. A. (1997). “A Hierarchical Model of Approach and Avoidance Achievement Motivation.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72, 218–232.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Elliot, A. J. & Thrash, T. M. (2002). “Approach-Avoidance Motivation in Personality Approach and Avoidance Temperaments and Goals,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(5), 804–818.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Eysenck, H. J. (1981). ‘Learning, Memory, and Personality,’ In H. J. Eysenck (Ed.), a Model for Personality. New York: Springer-Verlag.

Google Scholar

Furnham, A. (1992). ‘Personality at Work: the Role of Individual Differences in the Workplace,’ London: Routledge.

Google Scholar

Gattiker, U. E. & Larwood, L. (1988). “Predictors for Managers’ Career Mobility, Success and Satisfaction,” Human Relations, 41, 569-591.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Gattiker, U. E. & Larwood, L. (1989). “Career Success, Mobility and Extrinsic Satisfaction of Corporate Managers,” Social Science Journal, 26, 75-92.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Goldberg, L. R. (1990). “An Alternative Description of Personality: the Big-Five Factor Structure,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59, 1216 – 1229.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Greenhaus, J. H. & Callanan, G. A. (1994). ‘Career Management,’ The Dryden Press, Fort Worth, TX.

Google Scholar

Guthrie, J. P., Coate, J. & Schwoerer, C. E. (1998). “Career Management Strategies: the Role of Personality,” Journal of Managerial Psychology, Vol.13, Pp. 371-386

Publisher – Google Scholar

Howard, A. & Bray, D. W. (1994). ‘Managerial Lives in Transition,’ Unpublished Manuscript. Yale University.

Hwa, A. C. (2004). ‘Organizational Experiences and Employment Outcomes: The Impact of Subordinate Disability,’, Universiti Sains Malaysia

John, O. P. & S. Srivastava (1999). The Big Five Trait Taxonomy: History, Measurement and Theoretical Perspective. The Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research (2nd Ed)

Publisher – Google Scholar

Judge, T. A., Heller, D. & Mount, M. K. (2002). “Five-Factor Model of Personality and Job Satisfaction: a Meta-Analysis,” Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(3), 530-541.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Judge, T. A., iggins, C. A., Thoresen, C. J. & Barrick, M. R. (1999). “The Big Five Personality Traits, General Mental Ability and Career Success Across the Life Span,” Personnel Psychology 52, 621 – 652.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Judge, T. A. & Ilies, R. (2002). “Relationship of Personality to Performance Motivation: a Meta-Analytic Review,” Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 797 – 807.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Judge, T. A. & Kammeyer-Mueller, J. D. (2007). “Personality and Career Success,” University of Florida, Gainesviller

Publisher – Google Scholar

Jones, R. G. & Whitmore, M. D. (1995). “Evaluating Developmental Assessment Centers as Interventions,” Personnel Psychology, 26, 337 – 388.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Liao, C.-S. & Lee, C.-W. (2009). “An Empirical Study of Employee Job Involvement and Personality Traits: the Case of Taiwan,” Int. Journal of Economics and Management 3(1): 22 – 36

Publisher – Google Scholar

Mccrae, R. R. & Costa, P. T. (1987). “Validation of the Five-Factor Model of Personality Across Instruments and Observers,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(1), 81–90.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Mccrae, R. R. & Costa, P. T. (1991). “Adding Liebe und Arbeit: The Full Five Factor Model and Well-Being,” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 17, 232.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Mccrae, R. R. & Costa, P. T. (1999). “A Five-Factor Theory of Personality,” in L. A. Pervin & O. P. Johns (Eds.), Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research. New York, NY: Guildford Press.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Nabi, G. R. (1999). “An Investigation into the Differential Profile of Predictors of Objective and Subjective Career Success,” Career Development International . 4(4), 212-224.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Organ, D. W. & Lingl, A. (1995). “Personality, Satisfaction and Organizational Citizenship Behavior,” Journal of Social Psychology, 135, 339-350

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Petway, K. T. (2010). “Applying Adaptive Methods and Classical Scale Reduction Techniques to Data from the Big Five Inventory,”

Publisher – Google Scholar

Rasdi, R. M., Ismail, M., Uli, J. & Noah, S. M. (2009). “Career Aspirations and Career Success among Managers in the Malaysia Public Sector,” Journal of International Studies, Issues 9

Publisher – Google Scholar

Seibert, S. E. & Kraimer, M. L. (2001). “The Five-Factor Model of Personality and Career Success,” Journal of Vocational Behavior 58, 1-21

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Sekaran, U. (1992). Research Methods for Business: A Skill Building Approach, 2nd Ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Turban, D. B. & Doherty, T. W. (1994). “Role of Protégé Personality in Receipt of Mentoring and Career Success,” Academy of Management Journal 37, 3, Pp. 688-702.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Wayne, S. J., Liden, R. C., Kraimer, M. L. & Graf, I. K. (1999). “The Role of Human Capital, Motivation and Supervisor Sponsorship in Predicting Career Success,” Journal of Organizational Behaviour , 20(5), 577-595.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Zweig, D. & J. Webster (2002). ‘What are We Measuring? an Examination of the Relationship Between the Big-Five Personality Traits, Goal Orientation and Performance Intentions,’ Personality and Individual Differences 36 (2004), 1693- 1708.