Introduction

The precariat is the latest conceptualization of social class. Scholars have generally defined precariat as a state of vulnerability in daily life (see Standing, 2011; Butler, 2004). This notion about precarity has evolved into two distinctive perspectives. The first is approaching precarity as a form of social class, which examines the experience of people who suffered by precarity because of their position within the production process. The precariat is a working class which is placed right under the proletariat social class. The main characteristic of its member is that they work in a job with nonpermanent employment status and does not provide enough compensation for their well-being (Lee, 2016; Standing and Jandric, 2014; Davis and Kim, 2015). The second approach sees precariat as a social condition, which refers to a state of vulnerability and uncertainty that can be temporary or permanent and influence people’s emotion and behavior on their daily life (Han, 2018; Allison, 2012; Lloyd, 2009). However, the discussion of precarity that is associated with employment in state own institutions tends to be ignored. Several studies on this topic are usually associated with cases relating to nonpermanent employment status.

This article argues that the public sector has started to contribute to the growth of the precariat working class. All this time, employment in state own institutions are considered as an example of a job that provides stable employment status and financially prosperous. Therefore, working as a civil servant is considered as an achievement which guarantees a place in an established middle-class social stratification. However, there are emerging tendencies that more flexible employment characteristics are featuring on several types of employment in the public sector (Standing, 2011: 50; Tjandraningsih, 2016). As one of the examples, the Indonesian government recruits nonpermanent staff to fill vacancies in the state institutions, such as ministerial offices and public schools.

Jakarta provincial education office has issued Decree No. 1259 of 2017 that regulates the appointment of teachers and educational staff of public schools in Jakarta as employees under the Individual Employment Contract (IEC). IEC employees have an annual working contract with the provincial government which can be renewed annually based on certain considerations and recommendations from the principal of the school where the employee works. The enactment of this regulation marks the official beginning of a flexible job system in public schools under the provincial government of Jakarta.

The Decree is an example of public sector reform program known as the new public management (Verger et al, 2016: 8). State government and its bureaucracy has taken the path of liberalization, and step in the development process in order to nurture it in ways that will speed that process up (Wylde, 2017; Shahrukh and Jens, 2011). For the provincial government, the decree is a way to achieve two objectives. First, it can work as a solution to appease the demands of nonpermanent teachers who always request to be promoted as a permanent teacher in public schools. Second, the regulation is necessary as a part of the provincial budget efficiency. On the other hand, this regulation makes the discussion on precariat become more relevant. By this decree, the provincial government deliberately provides nonpermanent employment, which drives the growth of precariat class.

This article aims to enrich the study in the sociology of work, especially for the teaching profession. There are many facets of teacher profession, yet most of the study about the teacher is focusing on its professional feature, such as teachers productivity (Ahmadi, 2018), or teaching methods and teachers work management (Surachman 2017). Other studies also focus on teaching as a meaningful occupation that has the ability to provide self-esteem and sense of identity (Klimenko and Posukhova, 2018; Jenkins, 2017). However, those studies have yet put enough attention to the consequences of teacher’s employment status on an individual’s position in social stratification, and how nonpermanent employment status influences the well-being of teachers’ life. This article aims to cover these shortcoming studies of teaching profession.

A survey has been conducted to reveal how IEC teachers’ years of service influence their perception on the precarious side of their job. The survey involves 50 IEC teachers from 10 different junior high schools in the Ciracas District, East Jakarta, Indonesia. The result of this survey serves as the basis of arguments in this article.

Literature Review

Work and job are two different concepts in sociology. Working is more than being productive or doing something. It is actually a form of social relation which involves creative thinking, activity, and compensation. This work is sociologically defined as an activity to produce things that makes the actors receive reward equally with their endeavor (Grint and Nixon, 2015: 7). This definition of work has two empirical implications in terms of how people perceive work. Some people see work as an instrumental means to gain something that is valuable for them. This point of view put working as one of many other ways to build purchasing power. Others see that work has a substantial meaning which helps them to acquire self-esteem. This kind of work must have high intrinsic values in terms of specialty, creativity, and collective goal (Grint and Nixon, 2015 : 297).

However, acquiring a suitable job is not easy for everyone. Employees with a nonpermanent contract in the public sector are starting to grow. All this time, the public sector that are organized under the state, are perceived as the final frontier of employment source that provides stable jobs (Standing, 2011). However, this perception is not relevant anymore, since the state has started to apply more flexible employment management as part of a new public management strategy (Verger et al, 2016; Tjandraningsih, 2016; Wylde, 2017). This change is inevitable along with a more integrated global economy, which forces each country to organize their state budget as effectively and efficiently as possible. One of the consequences of this agenda is the enactment of flexible governmental employees management in every level of bureaucracies, including the state own educational institutions.

The implementation of nonpermanent employments in the Indonesian educational sector has been going on for a long time. This applies to both public and private schools, which are recruiting teachers and educational staff as nonpermanent employees. However, it is only recently that such practices are formalized by governmental regulation. This new phenomenon confirms the concern that the public sector is no longer immune to flexible work system (Standing 2011, Grint and Nixon, 2015; Tjandraningsih, 2016).

The study of a teaching profession in Indonesia mostly discusses a teacher as a professional work that is based on knowledge. It requires relatively high skills in terms of mastery of knowledge, and teaching skills (Ahmadi, 2018). As part of its professional acknowledgment, it is mandatory by law No 14 year 2005 about Teacher and Lecturer that each teacher should join the teacher certification program. Since the enactment of the law, certified teachers have become part of the indicators of the national educational quality. However, nonpermanent teachers have a small opportunity to enroll in the certification program. It is forbidden by law for teachers and educational staff to join the certification program if their employment contract is provided by the school principal. Only those with an employment contract that is provided by the government or a Foundation chairman can enroll in the teacher certification program (Surachman, 2016). Therefore, technically, only permanent teachers and educational staff can be professionally certified, while the nonpermanent teachers and educational staff are left behind.

Nevertheless, the existing studies on teaching profession do not draw enough attention to the differences between permanent and nonpermanent teachers. Nonperament teacher is a new global phenomenon. The number of people working as nonpermanent teachers has reach 350.000, which most of them are working in non-English speaking countries. Their presence in these schools are unchecked, monitored, or accounted in a single system. Previous studies suggest that most of them work in international schools, and they are teaching the middle-class offspring. In China, they become the new middle class (Bunnel, 2015; Poole, 2019). However, there are only a few studies that examine how this phenomenon could bring a negative impact in the future.

Several studies about teaching profession from several countries are focusing on the privilege of a teacher. In Australia, there is a study that examines teaching as a profession which provides self-esteem amidst its financial or other form of material compensations. Work also has psychological functions as a means of self-actualization (Jenkins et al, 2017; Allison, 2012). Similar to this study in Russia, there is also a study which concludes that teaching is a meaningful profession which provides identity basis and social status for its bearers (Klimenko and Posukhova, 2018). In Indonesia, teachers are called with the unsung heroes, since they work to educate the society without expecting the reward. Therefore, teachers have an esteemed position in society, especially the ones with strong social engagement (Arham and Suyanto, 2016). Meanwhile in Indonesia, existing studies on the consequences of teacher’s employment status are usually focusing on the association between employment status professionalism features of a teacher, such as the influence of workload between permanent teacher and nonpermanent teacher with their compensations and benefits (Setiawan and Budiningsih, 2014; Suprastowo, 2013).

The continuity of nonpermanent employment for teachers cannot be separated from the needs of the teaching staff. The proportion of nonpermanent teachers are around 30 percent of the total population of teachers nationwide. Through this amount of numbers, they influence several educational statistical indicators, including student and teacher ratio, permanent teacher and nonpermanent teacher ratio, and certified teacher and noncertified teacher ratio. Nonpermanent employees also have significant roles in school. Every school is trying to maintain the ideal number of those three statistical indicators. Besides, the school also has to maintain the workload of every teacher, since it is mandatory by law No 14 year 2005 that every teacher must fulfill their duty without exceeding the limit of 40 hours in a week. To achieve a balanced workload for teachers, recruiting nonpermanent teacher is always a common practice to fill the shortage of teachers (Setiawan and Budiningsih, 2014).

Despite being the most practical solution, hiring teachers with nonpermanent employment contract is problematic. Nonpermanent teachers are prone to experience precarious condition due to low compensation and uncertain career. This article will demonstrate how teachers with Individual Employment Contract (IEC) are experiencing precarity in all of their years of service.

Method

The survey data was obtained through printed questionnaires. There are 50 nonpermanent teachers who were involved as respondents, they work in 10 different Public Junior High Schools in Ciracas District, East Jakarta. The respondents give their response to the questions by filling the suitable option that represents their opinion by themselves.

The printed questionnaire consists of 50 questions. One question is to confirm the respondent’s years of service as nonpermanent teacher. The other 49 questions are grouped in seven precarious work dimensions. All the seven dimensions are based on the work of (Guy Standing) in his book (The Precariat Class) (Standing, 2011), which are: labor market security, employment security, job security, work security, skill reproduction security, income security, and representation security.

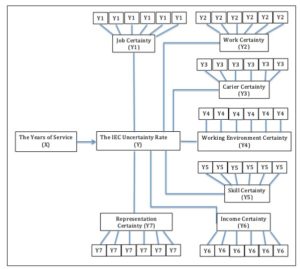

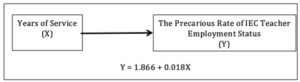

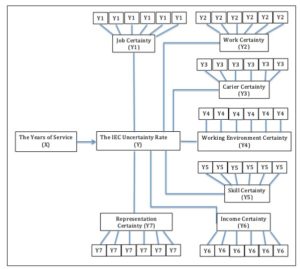

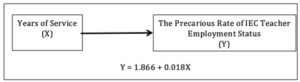

All collected data are analyzed using PSPP; an open statistical source computer program. The data analysis includes both descriptive and inferential analysis. The first step in the data analysis is synthesizing all data in every seven dimensions. Those dimensions then combine together to form the precarity of the IEC teachers’ variable, which serves as the dependent variable. The final step is measuring the regression analysis between the years of service with the IEC teachers’ perceptions. The framework of this research is depicted in figure 1.

Figure 1: Research Framework

Findings

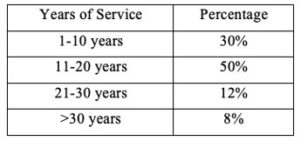

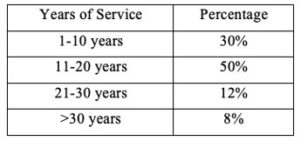

The independent variable in this research is the IEC teachers’ years of service. This variable is divided into four different groups. The first group is teachers with years of service between 1 to 10 years. The second group is teachers with 11 to 20 years of service. The third group is teachers with 21 to 30 years of service. The fourth group is teachers who have been working for more than 30 years. The proportion between all four groups are 30%, 50%, 12%, and 8% respectively, as depicted in chart 1.

Chart 1: Respondents’ Year of Service

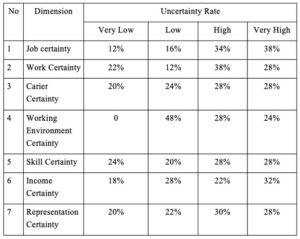

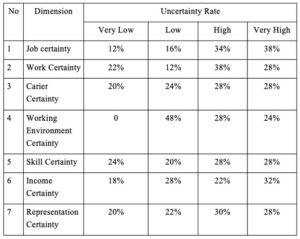

The dependent variable in this research is the precarious rate of the IEC Teachers employment status. The IEC teachers who are involved as respondents have different experiences among them. However, in general, all of them perceived several uncertainties in every dimensions of precarious work. The synthesis result of all items from each dimension is shown in table 2.

Table 2: The rate of uncertainty in seven dimensions of precarious features in the IEC teacher employment status

Most of the respondents perceived that their employment opportunity is highly uncertain. Their perception is actually similar with most of the workforce at the current time, who also think that it is getting tougher to land a job that is worth keeping. It is important to mention that all the respondents were paid teachers before they were promoted as the IEC teachers. They voluntarily accept their employment as paid teachers, even though they realized that their employment status granted them low financial compensation without other kinds of benefits.

Apparently, most of the respondents has difficulties to join associations that can represent their interests. The proportion of respondents who think that their representation is highly uncertain is 30 %, while those who think that their representation is very highly uncertain is 18%. This finding indicates that most of the respondents needs a group who can speak for them. The precarity that they suffer is hindering them to organize themselves, because their time is mostly spent at work.

From all of the seven dimensions, only working environment certainty is positively appreciated by most of the respondent. There are two main reasons for this. First, all of IEC teachers are familiar with their working environment. Only those who already became nonpermanent school staff can enroll in the IEC employment test. The second reason is that the nature of a teacher’s work is harmless. However, as a nonpermanent employee, IEC teacher has a low bargaining position in front of his school administrators and colleagues. These situations explain why none of the respondents perceived the uncertainty rate of their working environment is very low.

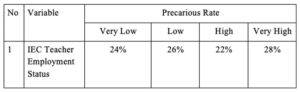

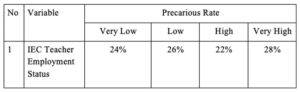

Table 3: The Precarious Rate of IEC Teacher Employment Status

The precarious rate of IEC Teacher employment status variable is the synthesis of all the seven precarious work dimensions. Based on the analysis, the highest proportion shows that most of the respondents perceived that their employment status is very highly uncertain. However, the values of each proportion are actually close to each other. Therefore, the result of the analysis can also be interpreted that several IEC teachers are satisfied with their job. Even though they experience the precarity features of their job, they can adapt to those situations. This finding is similar to what was already mentioned by Clara Han that precarity is a social feature on daily basis (Han, 2018). Employees who are in precarious condition can find a way to adapt and maintain their well-being. One of the ways is by working a side job to earn additional income, or simply work harder to demonstrate a good performance so that their employer grant them contract renewal.

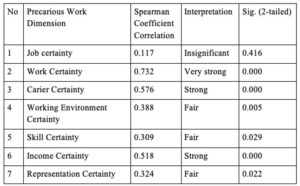

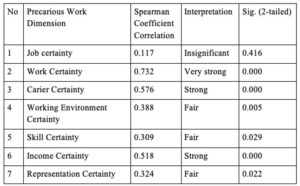

The Spearman coefficient correlation values of each dimension reflect the strength correlation between each dimension with the precarious rate of IEC employment variable. Among all seven variable dimensions, only job opportunity dimension has insignificant correlation coefficient value. While the other six dimensions have significant correlation values, as depicted in table 4.

Table 4: Spearman Coefficient Correlation Between Precarious Work

Dimensions and The Precarious Rate of IEC Teachers Employment Contract

The continuity of employment is a prominent aspect for a labor’s confident to plan their future. This aspect is represented in the employment contract. In the case of IEC teachers, their employment contract is more than just an agreement. Their contracts are issued by the provincial government which upgrades the employment status in their workplace. When their status was paid employees, they were actually at the bottom of the employee’s stratification. With the IEC employment contract, their status is raised beyond the paid employees. However, it does not change the fact that their job continuity is uncertain.

The second improvement of IEC teachers in comparison with the paid teachers is in the amount of their salary. The IEC teachers received a significant boost in their paycheck than before when their employment status was paid teachers. They now enjoy a paycheck that is equal to the official Provincial Minimum Salary. However, there is no additional benefit such as insurance and pensions. This makes the compensation received by the IEC teachers actually less than enough. In 2019, the paycheck received by each IEC teacher per month is 3.940.973 Indonesian Rupiah that is equal to 280 USD. That amount of money is barely enough to finance a life for a married couple. Their income uncertainty is also influenced by nonfinancial factors. They feel that their payment scheme is not fair, because it does not consider the nature of the job and the workload. Every IEC employee received the same amount of salary, whatever their job description is, whether they work as a teacher, an administration staff, or as a gardener. IEC teachers also received less salary than permanent teachers, even though IEC teachers sometimes have more workload than permanent teachers.

The next precarious side of IEC employment that are captured in the survey is the lack of career development in their job. IEC employment does not support career development. It is an employment contract with a specific job description that is mentioned in the employment contract (Jakarta Provincial Educational Office, 2017). This feature of their employment closes the possibility for them to work in a schools’ structural position.

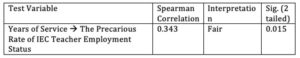

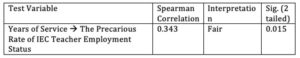

After both dependent and independent variables are established, the next step of the analysis is testing this research hypothesis. The correlation between the two variables is tested with spearman correlation, and the result is shown in table 5. The correlation between the two variables are considered as fairly correlated. This means that there is a possible influence of IEC teachers’ years of service to their perception of the IEC employment status. A regression analysis is used to clarify the possibility.

Table 5: Spearman Correlation between Independent and Dependent Variable

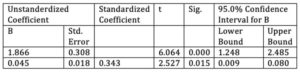

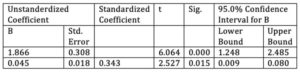

The result of regression analysis clarifies the positive influence of the years of service to the precarious rate of IEC teachers’ employment status. Based on the result, a regression model between the two variables constructed as Y = 1.866 + 0.045X, which can be interpreted that the longer IEC teachers years of service, the more their perception on the precarious features of their employment status is slightly increased.

Table 6: Regression Analysis on the influence of Years of Service to

The Precarious Rate of IEC Teacher Employment Status

Figure 2: Regression Model

The regression analysis in this research confirms that IEC employment status does not improve employees work certainty. Even though it is considered as an upgrade of employment status, the compensation and continuity are not enough to build confidence for the future. The uncertainty perception is slightly rising from time to time since the respondents feel that the compensation from their work is barely enough to provide for their life.

Discussion

The precariat working class has a place under the proletariat class in social stratification (Lee, 2016; Standing, 2011). This working class is struggling in the middle of a flexible job market which offers less permanent employment opportunity than the non-permanent one. The precariat has to coopt with the job that they have by spending more time to secure their income. This feature of precariat working class is similar to Karl Marx’s identification of the lumpenproletariat which refers to people/workers who are in a precarious situation for working in the periphery of the production chain (Han, 2018). They do not have class consciousness since they never hold a job for a long period of time, which also hinders them to be involved in any form of association because they do not have any luxury of time other than for work to provide their families.

The IEC teaching is a kind of employment that has some features of precarious work. Even though it is a knowledge-based work, the employment status gives the worker less compensation that is not equal to the specialty that is required for the job. The employment status is also not permanent, which adds a vulnerability aspect to the job. Not only because the period of the employment contract is relatively short, only for one year, but the employee does not also have any support to defend themselves if the administration in their workplace decides not to renew their contracts. These two features of IEC employment status make the job have a similarity with the job in the informal sector where the compensation is low and the continuity is uncertain (Lee, 2016). The two precarious features of IEC employment have put the IEC teachers in a complex situation to fulfill their duty because they also suffer from the precarity condition.

The regression model confirms the influence of the IEC teachers’ years of service to how they perceived the precarious side of IEC employment status. This finding provides a basis to argue that precarity condition is an ongoing situation which is caused by the weakening support of a job to provide a good life. The unintended result of the IEC employment policy is causing informalization of non-permanent employment in the public sector. The informalization in IEC employment status is identified in three aspects. The first aspect is the compensation for the job that does not correlate with the workload. All IEC employees receive the same amount of salary each month no matter what their educational background, work experience, and job descriptions are. IEC teachers who work in the class and outside the class, such as when they examine the student’s homework, are paid with the same amount as other IEC employees who are responsible to maintain the school garden. The second aspect is the uncertainty on the continuity of employment. This is probably the main aspect that concerns IEC teachers. Even though their employment contract is very likely to be renewed every year, they do not have direct influence on the decision-making process. They are also unable to defend themselves if the school administration decides not to give the contract renewal recommendation to the provincial educational office. The third aspect is the relatively low compensation. There is a high probability that the amount of salary is completely used to provide the basic needs so that the teachers do not have any share for saving.

To alleviate the alienation of nonpermanent teachers from their career, the school could provide them with training and other means that facilitate the teachers to improve their competency. Professional training provided by the schools or government would help teachers that are required to be creative, critical, and able to collaborate with the students and their colleague (Walkland, 2017). Even though nonpermanent teachers do not have a career path, however, they would appreciate their work according to the level of involvement in their workplace.

This survey also provides an empirical stand to argue that precarity should be interpreted as a social condition. The respondent’s profession is considered as meaningful and has a high esteem in society. Therefore, even though the teacher perceived that they are experiencing similar precarious feature with industrial labor, the IEC teacher does not consider themselves as a part of the proletariat class. The terminology of industrial labor is associated with semi-skilled and routine job. On the contrary, the teaching is a knowledge-based occupation. Even though their employment status is non-permanent, they have the creativity to coopt with the disadvantages of their employment status. Therefore, their precarity situation is considered to be temporary.

Conclusion

IEC teacher employment status is problematic. Working as a teacher gives a sense of high esteem for teachers. However, their employment status has similar features with the informal job, which is depicted in the uncertainty of their compensation, employment continuity, and their future life. The practical solution to coopt with their precarity conditions are generating additional income. Such a strategy shows that the IEC teachers are eager to alleviate their vulnerability, including sacrificing their productivity as a teacher.

The precarity that is suffered by the IEC teachers also provides an argument to interpret the concept of precariat as a type of social condition. This argument is based on the survey finding, which concludes that most of the respondents perceived that they are lacking group representation. Their main interest to build a good life force them to use most of their time searching for additional income. They do not have enough time to organize themselves through a dedicated group or association. As the result, the IEC teachers does not have class consciousness, which is the drive to initiate class struggle.

The regression model that is constructed in this research confirms the influence of years of service to IEC teachers’ precarity perception on their employment status. This finding is a base argument for future studies on the impact of Individual Employment Contract to employeesˊ productivity and schools performance.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

References

- Allison, A. (2012) ‘Ordinary refugees: social precarity and soul in 21st century Japan,’ Anthropological Quarterly, 85 (2), 345-370

- Arham, N and Suyanto, T. (2016) ‘Makna profesi guru honorer di yayasan pendidikan pondok pesantren Al-Muniroh kecamatan Ujung Pangkah Kebupaten Gresik,’ Kajian Moral dan Kewarganegaraan. 02 (03), 547-561

- Grint, K and Nixon, D (2015) The sociology of Work, Polity Press, USA.

- Han, C. (2018). ‘Precarity, precariousness, and vulnerability,’ The Annual Review of Anthropology, 47, 331-43

- Jenkins, K., Charteris, J. Tyrrell, B., Michelle, and Jones, M. (2017) ‘Emotions and casual teachers: implications of the precariat for initial teacher education,’ Australian Journal of Teacher Education. 42 (12.10) 162-179

- John W Cresswell (2003) Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mix Methods Approaches, Second Edition, Sage Publication

- Keith Grint dan Darren Nixon, (2015) The Sociology of Work, Polity Cambridge

- Klimenko, L, and Posukhova, O. (2018) ‘School teachers’ professional identity in the context of the precariatization of social and labor relations in large russian cities,’ Voprosy Obrazovaniya, 3, 8-35

- Lee, CK. (2016) ‘Precarization or empowerment? reflection on recent labor unrest in China,’ The Journal of Asian Studies, 75 (2) 317-333

- Lloyd, M.S. (2009) Towards a cultural politics of vulnerability: precarious lives and ungrievable deaths, Judith Butler’s Precarious Politics: Critical Encounters, Carver, T., and Chambers, S.A.(eds), Routledge, London.

- Poole, A. (2019). Internationalised school teachers experiences of Precarity as part of the global middle class in china: Towards resilience capital. The Asia – Pacific Education Researcher, , 1-9. doi:http://remote-lib.ui.ac.id:2068/10.1007/s40299-019-00472-2

- Setiawan, H., and Budiningsih, T.E. (2014) ‘Psychological well-being pada guru honorer sekolah dasar di kecamatan wonotunggal kabupaten batang,’ Educational Psychology Journal, 3 (1), 8-13

- Shahrukh, R., and Jens, C. (2011) Towards New Developmentalism Market as Means rather than master, Taylor & Francis e-Library. London and New York

- Standing, G. (2011) The Precariat The New Dangerous Class, Bloomsbury, New York.

- Standing, Guy (2014) ‘The precariate and class struggle (o precariado e a luta de classes),’ Revista Critica de Ciencias Sociais, 103, May 2014, 9-24

- Suprastowo, (2013) ‘Kajian tentang tingkat ketidakhadiran guru sekolah dasar dan dampaknya terhadap siswa (teacher absenteeism study on primary school and its impact on student)’ available : https://jurnaldikbud.kemdikbud.go.id/index.php/jpnk/article/viewFile/106/103

- Suhandani, D, and Julia. (2014) ‘Identifikasi kompetensi guru sebagai cerminan profesionalisme tenaga pendidik di kabupaten sumedang (kajian pada kompetensi pedagogik),’ Jurnal Mimbar Sekolah Dasar, 1 (2), 128-141, Available: upi.edu/index.php/mimbar/article/download/874/608

- Surachman, E. (2016) Manajemen Pendidikan-Tenaga Kependidikan, Laboratorium Sosiologi UNJ, Jakarta.

- Tjandraningsih, I. (2016) ‘State-sponsored precarious work in Indonesia,’ SAGE Publication American Behavioral Scientist, 57 (4), 403-419

- Tristan Bunnell (2015): Teachers in international schools: a global educational ‘precariat’?, Globalisation, Societies and Education, Routledge DOI:, retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2015.1068163

- Verger, A, Fontdevila, C, and Zancajo, A. (2016) The Privatization of Education: a political economy of global education reform, Teachers College, Columbia University.

- Walkland, T. A. (2017). “Something to just hold on to”: Occasional teaching and collaborative inquiry in precarious times (Order No. 10623153). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (1992423976). Retrieved from https://remote-lib.ui.ac.id:2076/docview/1992423976?accountid=17242

- Wylde, C. (2017), Emerging Markets and the State Developmentalism in the 21 st Century, Palgrave Macmillan, London.