Introduction

Distance learning is not a new phenomenon in the 21st century, but it functioned quite differently in the 2020-2021 academic year. Due to the unpredictable dynamics of the COVID-19 pandemic, most educational institutions have switched to distance learning, using online educational platforms. This resulted in the necessity to examine the students’ perspective, to check their level of satisfaction with distance learning in changed circumstances (when distance learning became a basic form of education, instead of being complementary to traditional learning).

Gnieznienska Szkola Wyzsza Milenium, like other universities in the world, had to face this challenge, and so did lecturers and students. The context of building relationships with students has completely changed – it moved from the university to homes. Non-verbal messages, especially from students, have been kept to a minimum. Everyone had to adapt to very big changes, so it is worth analyzing the effects. It was also a huge organizational challenge, consisting in launching access to the platform, which was designed to enable effective teaching, not just communication. First of all, the role of the lecturers was very important, as they had to become guides on the platform they were only just getting to know. It turned out that not only didactic skills are crucial here, but also technical. The students’ skills were also important. For this reason, one of the key factors analyzed were the competences of students related to distance learning. However, competences alone will not ensure full success in distance learning if students do not have adequate resources, which was also the subject of this study. It was assumed that all the above-mentioned factors could be strongly correlated with students’ satisfaction with distance learning. In research on student satisfaction conducted in various countries, many factors influencing satisfaction with distance learning were identified, including: preparation for learning – including student competences, student involvement – primarily in terms of resources, organization of learning by lecturers and relations between students and lecturers, as well as relations in the group of students (Dziuban et al. 2015, Longo et al. 2016, Nguyen et al. 2019, Green et al. 2015, Owston et al. 2013). In a study by a Vietnamese team, the overall quality of distance learning was positively related to student satisfaction, which in turn positively influenced their loyalty (Nguyen et al. 2019).

For universities competing for students, as is the case with Polish non-public universities, students’ satisfaction with the education process is crucial, not only because of the effectiveness of the teaching process, but also because of the perception of the university by potential candidates for studies. In this perspective, the identification and conscious creation of factors determining satisfaction become the core of managing the university. The conducted study aimed to indicate the commendations regarding the effective work of universities in these new circumstances, especially because of the uncertainty of returning to the pre-pandemic teaching channels and methods.

Distance learning

Distance learning has a long tradition. Teaching using correspondence education, television, magazines, has become a forced necessity especially in low-population density countries. An equally important reason for the introduction of distance learning was the lack of access to formal and non-formal education institutions in far-off places. The increase of the technical capabilities of data transmission allows, in many countries, fortifying a lack of access to educational institutions with e-learning platforms (Tomczyk 2020).

In the literature, distance learning is most often described as a method that uses indirect contact instead of direct contact between the learner and the teacher (Juszczyk 2002). Distance learning is thus defined as learning activities in formal, informal or non-formal areas that are supported by information and communication technologies to reduce distances, both physical and mental, and to increase interactivity and communication between learners and educators (Bozkurt 2019). In many countries, however, distance learning is perceived (apart from crisis situations, such as the COVID-19 pandemic period) as one of the complementary teaching methods.

Satisfaction

Satisfaction is a feeling of delight or frustration caused by the difference between expectations and reality (Ahmad et al. 2021). Satisfaction with distance learning is an important issue under scrutiny in the times of the pandemic, providing information on, inter alia, the quality of distance learning (Zhou, Zhang 2021). Various methods of measuring the level of satisfaction are used in the research. One of the proposals is to create an index based on the answers of students who were to respond to 4 statements: I am very satisfied with university services; University met my expectations; University fulfilled my aspirations; University met my needs (Parahoo et al. 2016). Another very popular solution is the study of the level of satisfaction “with something” by asking whether someone would recommend that “something” to others (Selhorst et al. 2017; Eom, Ashill 2016; Sinclaire 2012) or by asking directly to what extent the respondent is satisfied with “something” (Eom, Ashill 2016; Dziuban et al. 2015; Alqurashi 2019). Building an index based on direct questions about satisfaction with particular aspects of the research subject and the questions about general satisfaction with the subject of the research was also used (Wei, Choi 2020). Research on the level of student satisfaction was conducted already during the COVID-19 pandemic by, among others: Fatani from Saudi Arabia (Fatani 2020) and the Chinese team: Ho, Cheong, Weldon (Ho et al. 2021).

Hypothesis Development

Preparation for learning (competences) of the students

H1: There is a positive correlation between students’ competences related to preparation for distance learning and their satisfaction with distance learning.

In 2016, Longo, Gunz, Curtis and Farsides (Longo et al. 2016), based on a scale developed in 2001 (Deci et al. 2001) and an adapted version of Sheldon and Hilpert’s research (2012), conducted research on psychological needs and satisfaction associated with better well-being related to studying and work. Referring to the existing basic theory of needs, the authors confirmed that satisfying them can promote well-being and, at the same time, frustrate them when one or all of them are unsatisfied. The article also includes competences among the analyzed factors. Among the competences related to distance learning, the following are of fundamental importance: knowledge of the educational platform within which the classes are conducted, the ability to use electronic library resources and the ability to work in the programs used during classes (Word, Excel). Moreover, it has been shown that deficiency in the above-mentioned skills can significantly reduce the level of satisfaction with distance learning (Aristovnik et al. 2020). Other authors emphasized also the relationship between preparation for learning, understood as familiarization with applications required in class, and student satisfaction (Ho et al. 2021).

Student involvement in terms of resources (including time)

H2: There is a positive correlation between students’ involvement in terms of resources and their satisfaction with distance learning.

Studies on the level of satisfaction with distance learning were conducted also before the pandemic. The authors investigated the possible relationship between satisfaction with distance learning and the theory of psychological contracts (Dziuban et al. 2015). The results of these studies identified three basic components of satisfaction, including broadly understood commitment (also in terms of resources). The research from 2020 (Fatani 2020) examined, e.g., access to technology (one of the determinants of students’ involvement in terms of resources) as a factor that may determine the level of student satisfaction with distance learning. The results of research conducted in Indonesia regarding distance learning showed that student involvement in terms of resources is important for their satisfaction. The above-mentioned article confirmed the hypothesis that students’ involvement has a positive impact on their satisfaction (Muzammil et al. 2020). The authors cited, inter alia, research from 2016 (Gray, DiLoreto, 2016), which included similar analysis conducted also before the pandemic. Therefore, students should not only have access to the necessary resources (including library and software), but also have the time needed to participate in classes and remote meetings with students preparing joint projects.

Martin and Bolliger (2018) also confirmed that involvement is critical to students’ learning and satisfaction in the process of acquiring knowledge.

Brazilian research suggests that improving system quality (access to a good Internet connection, communication software and specialized software tools) has a positive effect on satisfaction with distance learning (Cidral et al. 2018).

The aforementioned Chinese research team also showed that resource availability and students’ involvement over time are important in predicting the satisfaction of distance learners. In this case, factors such as: access to specialized software at home, access to library resources, time to participate in remote classes, time for meetings in student groups, were taken into account (Ho et al. 2021).

The basic prerequisites for the successful use of new technologies in distance education should be, among others: individualization of the learning process (and thus access to the necessary tools, software at home) and enabling learners to look for their own path – learning at their own pace and within their own learning style, consolidation of the independent use of educational resources and continuous development (Plebanska, 2020).

Influence of lecturers on satisfaction with distance learning

H3: There is a positive correlation between lecturers’ organization of distance learning and students’ satisfaction with distance learning.

H4: There is a positive correlation between the relationship with lecturers and students’ satisfaction with distance learning.

The presence and role of lecturers was emphasized by many authors both in the works before and during the pandemic (e.g., Van Wart et al. 2020; Sun et al. 2008; Green et al. 2015), who indicated the importance of emotional support provided by lecturers, feedback and course structure (So, Brush, 2008; Eom et al. 2006; Parahoo et al. 2016). Organization of education is a very important aspect that may affect the satisfaction of students with distance learning (Lee, Rha, 2009); its significant impact has been demonstrated by Sharma et al. (2020). Palmer and Holt (2009) pointed to the great importance of students’ understanding of what is expected of them. One of the considerations in previous distance learning satisfaction surveys was whether students feel motivated (Pena 2010, Eom, Ahill 2016). The importance of communication and interaction with lecturers was analyzed by Bray et al. (2008), Kuo et al. (2013). The most basic form of interaction is providing feedback to students after completing a specific task (Shea et al. 2002). Feedback should be translated into evaluation (Dykman, Davis 2008) and being regular (Kuh 2003). In the research conducted by Holsapple and Lee-Post (2006) on feedback provided to students during on-line learning, feedback was considered an element of the quality of services, and its features such as promptness, responsiveness, fairness, competency, and availability, were indicated. Other authors emphasize the active presence of lecturers in discussion forums, asking questions and conducting asynchronous discussions as an important type of interaction with students (Nandi, Hamilton, Harland 2012). In another study, the authors confirmed a statistically significant relationship between the interactions of lecturers and students and the level of satisfaction of the latter (Sebastianelli et. al., 2015).

Relations with students and satisfaction with distance learning

H5: There is a positive correlation between relations with students and students’ satisfaction with distance learning.

When analyzing the satisfaction with distance learning, many researchers also took into account the relationships with students (Owston et al 2013; Reisinger, Walker 2021). The importance of interactions not only with lecturers but with students and their influence on student engagement is already obvious among researchers of this subject (Astin 1993). Sher (2009) and Strang (2011) showed a strong positive relationship between student interactions and their level of satisfaction with on-line learning, who also indicated the impact of these interactions on students’ achievements.

Conditions for distance learning

H6: There is a positive correlation between the conditions for distance learning and students’ satisfaction with distance learning.

Korean authors focused on the relationship between the conditions for distance learning and students’ satisfaction with this form of learning. They noted that there are some positive features of distance learning in a crisis like the COVID-19, such as: comfortable learning environment and efficient use of time, while network instability and reduced concentration (e.g., caused by the presence of other household members) turned out to be the causes of students’ complaints, and thus lowered their sense of satisfaction with on-line classes (Shim, Lee 2020). Research at one of the British universities also noted that the determinant of perceived satisfaction with distance learning is quality of the technical system – a good-quality computer and the Internet (Al-Fraihat et al. 2020). Yawson and Yamoah (2020) also drew attention to the scientific community, although they also distinguished gender and age differences as variables differentiating the level of students’ satisfaction with distance learning.

Differentiation in the level of dependence of variables for the 1st, 2nd and 3rd year of first-cycle studies

All hypotheses were formulated accordingly:

H7A: The difference between the highest and the lowest level of correlation between students’ competences related to preparation for distance learning

(V1) and their satisfaction with distance learning (S) for individual years of first-cycle studies is at least 0.2.

H7B: The difference between the highest and the lowest level of correlation between V2 and S for individual years of first-cycle studies is at least 0.2.

H7C: … V3 and S …

H7D: … V4 and S …

H7E: … V5 and S …

H7F: … V6 and S…

The level of students’ satisfaction with distance learning, depending on the year of study, was investigated by Polish authors (Brzozka et al. 2021). They distinguished several factors affecting satisfaction and analyzed the differences in the mean of answers to questions depending on the year of study. It turned out that there was a large discrepancy between the responses of first-year students and older students. The authors concluded that such large differences result from the fact that first-year students did not have a comparison with the traditional examination session. These students also saw no problem with contacting the lecturers and rated the lecturers’ preparation to conducting on-line classes the highest, compared to the assessment of students from the four consecutive years. Also, in the study by the Chilean team, the authors noticed differences between the responses of first-year students and higher-year students (Pérez-Villalobos et al. 2021). First-year students were more satisfied with distance learning than their older peers. The same was the case in the Vietnamese (Dinh, Nguyen 2020) and Indonesian (Amir et al 2020) studies. Researchers in the USA also focused on similar dependencies in their research (Cole et al. 2014, Liu, Haque 2017), each time analyzing the year of study (in the second case also age) in comparison with individual factors influencing the level of learners’ satisfaction.

Study Design

The survey was conducted among students of Gniezno College Milenium on June 2-21, 2021, using the online survey technique, which was caused by the pandemic situation in Poland. We also decided that the request to fill in the questionnaire distributed in this way will most likely be answered by students who efficiently use the Internet for learning and, above all, who are sensitive to the stimuli transmitted through this channel. We pretested the questionnaire using a small sample of management and pedagogy students who had studied at Gniezno College Milenium at least 4 months. In order to improve clearness, some items were rephrased or cut out. Aiming to reduce the potential for any halo effects, a few items were negatively worded, and the order of presentation was randomized. Similar procedure was used by Sebastianelli (2015). The survey questionnaire included indicators for each of the studied variables. The questions could be answered on a 5-point scale – from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5).

Measures

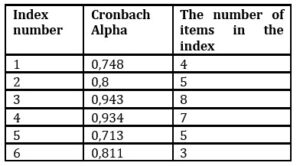

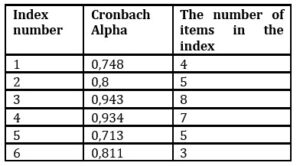

The following statement was chosen to measure the level of satisfaction with distance learning: “I can recommend Gniezno College Milenium to my friends”. The use of similar statements is made by, inter alia, Kotler and Keller (2011). From 3 to 8 statements were used to measure the following variables: 1. Students’ competences related to the preparation for distance learning at Gniezno College Milenium (Variable 1 – V1);2. Involvement of Gniezno College Milenium students on the basis of resources (V2);3. Organizing distance learning by Gniezno College Milenium lecturers (V3);4. Relations with the lecturers of Gniezno College Milenium (V4);5. Relations with Gniezno College Milenium students (V5);6. Conditions for distance learning (V6). The items assessing the abovementioned areas (1-3, 5, 6) were adapted from Ho (et al. 2021) and adjusted to the context of non-public higher education institutions, and items assessing relationship with teacher were adapted from Cayanus and Martin (2008) and adjusted as well. Following the reliability analysis, indices were built from these statements. All the Cronbach Alpha indices ranged from 0.713 to 0.943. Detailed information on the value of the Cronbach Alpha coefficient for indices is included in Appendix 2. In order to investigate the relationship between the index variables and the level of satisfaction, the Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient test was performed. Spearman’s rank correlation test coefficient in the range 0-0.3 means negligible correlation, while in the range 0.3-0.5 low positive correlation, and the correlation in the range 0,5-0,7 means moderate positive correlation, in the range 0,7-0,9 high positive, above 0,9 very high positive (Mohammad et al. 2019).

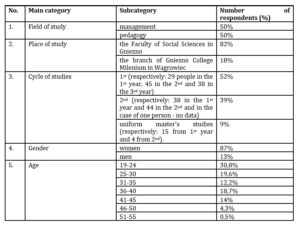

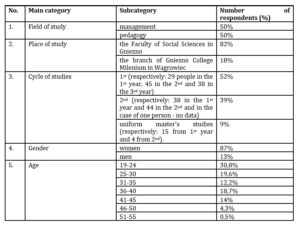

Sample

The developed questionnaire was distributed to all Gniezno College Milenium students (506 people). Ultimately, 214 returns were obtained. The results of the conducted research showed that we are dealing with a homogeneous group of respondents. An attempt was made to find differences in the level of satisfaction for gender, age, field of study, faculty, year of study. No statistically significant differences were found in the level of satisfaction for any of the above-mentioned characteristics, except for the year of study. The detailed information about the sample is included in Appendix 3.

Results

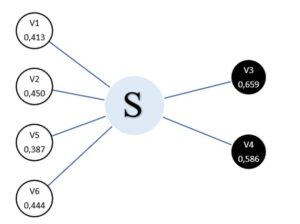

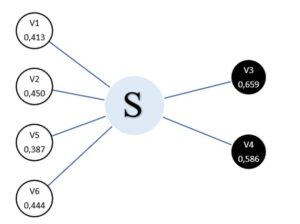

Factors correlating with satisfaction with distance learning

After conducting the Spearman’s rank correlation test to verify the hypotheses, it was found that there are no grounds to reject any of the six hypotheses. Moreover, a high relationship was found between the variables of the H3 and H4 hypotheses, and therefore there is a moderate positive correlation between lecturers’ organization of distance learning and students’ satisfaction with distance learning (rS = 0.659) and there is a moderate positive correlation between relations with lecturers and students’ satisfaction with distance learning (rS=0,586).

For the other four hypotheses, the correlation is low positive.

Statements (items) included in the above-mentioned variables and the level of their correlation with the variable – satisfaction with distance learning are included in Appendix 1.

The results of the analysis are presented graphically below (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Factors correlating with satisfaction with distance learning

S – satisfaction; V(variable)1 – students’ competences related to preparation for distance learning; V2 – involvement in terms of resources; V3 – organizing distance learning by lecturers; V4 – relations with lecturers; V5 – relations with students; V6 – conditions for distance learning.

Source: Authors’ own preparation based on their own research, N=214.

Satisfaction with distance learning is most strongly correlated with two factors related to lecturers, i.e. the organization of distance learning by lecturers and relations with lecturers, the analysis of which will be discussed later in the article.

It is also worth noting that each of the other analyzed factors (student competences, student involvement in terms of resources, relations with other students, conditions for distance learning) is correlated with the satisfaction with distance learning at a low positive level. (rS>0,3).

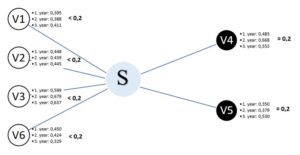

Year of studies as a moderating variable

According to the authors and referring to the previously mentioned sources, the year of study may be the key moderating variable for the dependencies analyzed in this article (H1-H6).

Students of each year of studies had significantly different experiences with distance learning. First-year students studied in a traditional way (within the facilities of the university) for the first 2 meetings (2 weekends), they spent the remaining time of their studies in the first year studying remotely. Second-year students studied the first semester within the facilities of the university and studied remotely for the next 3 semesters. 3rd year students had the longest full-time study experience, as much as 3 semesters and the same number of semesters students studied remotely. According to the authors and based on the previous above-mentioned research, this is a strong basis for formulating further hypotheses.

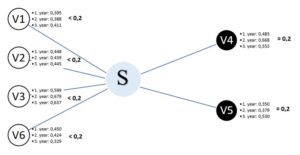

Therefore, the 7A-7F hypotheses were formulated. In order to verify them, the value of the Spearman’s rank correlation index (rS) was compared for the relationship between distance learning satisfaction and the variables V1-V6 for the 1st, 2nd and 3rd year of first-cycle studies. Second-cycle students were excluded from this analysis because their previous experience of studying at first-cycle studies at various universities could have an uncontrolled impact on their responses.

The results of the analysis are presented below.

Hypothesis 7A should be rejected – The difference between the highest and the lowest level of correlation between students’ competences related to preparation for distance learning and their satisfaction with distance learning for individual years of first-cycle studies is lower than 0,2. Similarly, hypotheses 7B, 7C and 7F should be rejected. There are no grounds to reject 7D hypothesis – The difference between the highest and the lowest level of correlation between relations with lecturers and students’ satisfaction with distance learning for individual years of first-cycle studies is about 0,2.

Similarly, there are no grounds to reject 7E hypothesis.

Detailed results are presented on Figure 2.

Figure 2: Factors correlating with satisfaction with distance learning for the 1st, 2nd and 3rd year of first-cycle studies

The meaning of the symbols is the same as for Figure 1.

Source: Authors’ own preparation based on their own research, N=214.

It is worth noting that for the V4 and V5 variables, i.e., the 7D and 7E hypotheses, the difference was the largest and amounted to approximately 0.2. Both variables concerned the relationship, one – with lecturers, the other – with students. This confirms the importance of the relationship in the context of assessing the level of satisfaction with distance learning, taking into account the year of study. Distance learning, compared to learning within the facilities of the university, offers completely different possibilities of building them.

For the remaining variables, the difference between the highest and the lowest correlation did not exceed 0.2, so the year of study was not of great importance in these cases.

Conclusions And Recommendations

Despite the crisis, the students indicated a high level of satisfaction with distance learning. A similar situation was also observed by the researchers cited above in other countries, e.g., in Vietnam (Dinh, Nguyen 2020) and Indonesia (Amir et al. 2020).

Our research showed that there is a high positive correlation between the relations of students with lecturers and their satisfaction with distance learning, while the correlation between the relations of students with their colleagues and satisfaction with distance learning is average and the lowest of all. The pandemic can be perceived as crisis situation and as such prompts us to maintain strong relationships with people with more experience (turn to authority) (Pérez-Villalobos et al. 2021).

In the era of the COVID-19 and distance learning at Gniezno College Milenium, students define their satisfaction with the education process primarily in relation to the lecturer. This is true both at the level of the organization of classes (H3) and in relation to the (virtual) relationship that is created between the lecturer and the student (H4). This means that it should be determined how to consciously build virtual relations between the lecturer and the student, valuable from the perspective of the didactic process and the image of the university.

These undoubtedly differ significantly from those carried out within the framework of full-time education.

In order to understand this difference and establish the key variables defining the relationship in question, it is worth using Goffman’s (1959) dramaturgical analysis. It is possible to identify the most important differences between distance learning and classroom learning, which will determine the nature of the lecturer-student relationship.

In this context, it is worth looking at the basic factors determining the nature of the subject relationship in both types of education and indicating the most important differences determining the relationship between the lecturer and the student, so that one can consciously influence them and thus create the desired level of satisfaction with the student-lecturer relationship as part of distance learning.

The first is space, in the dramatic perspective – the stage. In the case of full-time education, it is a lecture hall, the spatial organization of which makes it easier to assume the role of an actor (lecturer) and viewer (audience, i.e., students). The lecturer who enters the room is immediately physically distant from the students, often goes up the platform, or even the rostrum, which emphasize his social role, but which must not be forgotten, first of all facilitate his “performance”. Distance learning is also associated with the specific location of the lecturer, which is most often visible to all participants, and, similarly to stationary learning, gives the floor, indicates the people who are to answer the question.

The key change is related to the “audience”. In classroom teaching, it is a rather collective actor (a group of students) embedded in the common space of the room. In distance learning, it is difficult for students to present such a common “spectacle”, much more often, stimulated by the lecturer, they face him, alone. Nevertheless, the situation is to some extent to their advantage since their individual “performance” is embedded in the home space – this should provide a sense of comfort, convenience, and be the basis for self-confidence and self-esteem and the actor (student) can direct a stage on which he plays his spectacle.

The resource that a student in classroom classes has at his disposal is himself/herself. In the online classes, the impression he/she wants to get depends on a larger group of factors like: the space of the house visible on the viewers’ screens, and resources – the quality of the Internet connection, the performance of the equipment he uses (H2). Digital competences (H1) are also of great importance here, which may decide not so much about the success of a performance staged by a student, but even about whether it will be staged at all (in the surveyed group there are still many people who, for various reasons, are not able to effectively use their hardware resources or link parameters). Thus, effective control of a greater number of variables that determine the success of a student’s “spectacle” is difficult; it becomes more understandable why the respondents so strongly emphasized the importance of the relationship with the lecturer. Possible disruptions, such as a child suddenly appearing on the lap of a parent-student, noises coming from the apartment or house – which were not organized with virtual classes in mind (H6), often require new reactions from the lecturer, unheard of in classroom education. This “entrance” to the students’ houses, but also to the lecturer’s house, reduces the anonymity of the student-lecturer relationship, and possible disturbances during the “performance” expose equipment, competence, spatial deficits, or even in the area of relations with other members of the household, which gives the individual character to the relationship in question. In distance learning, the relationship with students is of a great importance for both – the student presenting his own thoughts and for the lecturers looking for confirmation of understanding of the presented content.

Distance learning is more like a face-to-face relationship set in a private space; it is richer by personal context, less anonymous, less dependent on colleagues (H5). These factors lead to the conclusion that the relationship with the lecturer in distance learning is of a different nature than in the pre-pandemic times, but surprisingly, it is also richer in terms of content, and thus, as confirmed by research, more important in terms of satisfaction.

The conducted study confirmed the important role of lecturers in building student satisfaction with distance learning, both in the area of organizing distance learning and building relationships with students. Therefore, these are the key variables that universities should focus on. The teaching context, which has changed so much, forces the use of completely new teaching methods, engaging students, conducting group work and class discussions. On the other hand, the relationships built with the lecturers gain significance. Thus, new types of training for teachers including all aforementioned factors should be introduced. In addition, when introducing e-learning, it is worth paying attention to the availability of resources necessary for students – analyzing especially before introducing new tools, e.g., software with high hardware requirements.

Limitations And Future Research

Although 42% of Gniezno College Milenium students were surveyed using the online survey technique, we did not manage to avoid its limitations – we probably reached people sensitive to stimuli coming from the Internet. The study was not carried out with a representative method. Nevertheless, we believe that the conclusions related to distance learning should be taken into account by universities’ authorities. In the future, it is planned to deepen this research by enriching it with new variables and adding lecturers’ perspective.

References

- Ahmad S. Ch., Batool A., Naz S., Qayyum A. (2021), ‘Path Analysis of Customer Satisfaction about Quality Education in Pakistan Universities’, IlkogretimOnline – Elementary Education Online; Vol 20 (Issue 5): 729: 728-743, [Online], [Retrieved July 7, 2021], http://ilkogretim-online.org; doi: 10.17051/ilkonline.2021.05.77.

- Al-FraihatD, Joy M, Masa’deh R, Sinclair J. (2020), ‘Evaluating E-learning Systems Success: An Empirical Study’, Computer Human Behaviour 102: 67–86. [Online], [Retrieved July 7, 2021], https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.08.004

- Alqurashi (2019), ‘Predicting student satisfaction and perceived learning within online learning environments’, Distance Education, VOL. 40, NO. 1, 133–148. [Online], [Retrieved July 7, 2021], https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2018.1553562.

- Amir LR, Tanti I, Maharani DA, Julia V, SulijayaB, Puspitawati (2020), ‘Student perspective of classroom and distance learning during COVID-19 pandemic in the undergraduate dental study program Universitas Indonesia’, BMC Medical Education, 20: 392. pmid:33121488. [Online], [Retrieved July 30, 2021], https://bmcmededuc.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12909-020-02312-0

- Aristovnik, KeržičD. Ravšelj D, Tomaževič N., Umek L. (2020), ‘Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Life of Higher Education Students: A Global Perspective’, Sustainability. 12(20): 8438. [Online], [Retrieved July 7, 2021], https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208438

- Bozkurt A. (2019), From distance education to open and distance learning: a holistic evaluation of history, definitions, and theories. In: Sisman-Ugur S, EskişehirKG, editors. Handbook of research on learning in the age of transhumanism. IGI Global: Turkey.

- Bray, E., Aoki, K, & Dlugosh, L. (2008),’Predictors of learning satisfaction in Japanese online distance learners’, The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 9(3), 1-21.

- Brzozka A., Pekala N., Pokusa A., Pyzik N., Sobol , KaczmarczykK., Nalepa A. (2021), Satysfakcja studentow ze zdalnego nauczania w trakcie pandemii COVID-19: badanie empiryczne studentow Wydzialu Nauk Spolecznych Uniwersytetu Slaskiego w Katowicach, Katowice: Towarzystwo Inicjatyw Naukowych.

- Cayanus L., Martin M. M. (2008), ‘Teacher Self-Disclosure: Amount, Relevance, and Negativity’, Communication Quaterly,Vol. 56, No. 3, August. 332: 325-341. [Online], [Retrieved July 7, 2021], DOI: 10.1080/01463370802241492.

- Cidral A., Oliveira T., Di Felice M., Aparicio M. (2018), ‘E-learning success determinants: Brazilian empirical study’, ComputerEducation 122: 273–290. [Online], [Retrieved July 7, 2021], https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2017.12.001

- Cole, M. T., Shelley, D. J., & Swartz, L. B. (2014), ‘Online instruction, e-learning, and student satisfaction: A three yearsstudy’, The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 15(6). [Online], [Retrieved July 7, 2021], https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v15i6.1748

- Deci, E. L., Ryan, R. M., Gagné, M., Leone, D. R., Usunov, J., & Kornazheva, B. P. (2001), ‘Need satisfaction, motivation, and well-being in the work organizations of a former eastern bloc country: A cross-cultural study of self-determination’, Personalityand Social Psychology Bulletin, 27(8), 930-942.

- Dinh LP, Nguyen T. (2020), ‘Pandemic, social distancing, and social work education: students’ satisfaction with online education in Vietnam’, SocialWork Education; 00(00), 1–10. [Online], [Retrieved July 30, 2021], https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02615479.2020.1823365

- Dykman, C. A., & Davis, C. K. (2008b), ‘Online education forum – Part three: A quality online educational experience’, Journal of Information Systems Education, 19, 281–290.

- Dziuban C., Moskal P., Thompson J., Kramer L., De Cantis, Hermsdorfer A. (2015), Student satisfaction with online learning: is it a psychological contract? Online Learn.;19(2):2

- Eom S. B., Ashill (2016), ‘The Determinants of Students’ Perceived Learning Outcomes and Satisfaction in University Online Education: An Update’, Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education, Volume 14 Number 2, 185-214.

- Eom, S. B., Wen, H. J., Ashill, N. (2006), ‘The determinants of students’ perceived learning outcomes and satisfaction in university online education: An empirical investigation’, Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education, 4(2), 215-235.

- Fatani (2020), Student satisfaction with videoconferencing teaching quality during the COVID-19 pandemic, BMC Medical Education., 20(1):396. [Online], [Retrieved July 7, 2021], https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02310-2 PMID:33129295

- Goffman, E. (1959), Presentation of self in everyday life. Garden City, N.Y., Doubleday.

- Gray, J. A., DiLoreto, M. (2016), ‘The effects of student engagement, student satisfaction, and perceived learning in online learning environments’, International Journalof Educational Leadership Preparation, 11(1).

- Green, H. J., Hood, M., Neumann, D. L. (2015), ‘Predictors of student satisfaction with university psychology courses: A review’, Psychology Learning & Teaching, 14(2), 131-146.

- Ho I. M. K., Cheong K. Y., Weldon A. (2021), Predicting student satisfaction of emergency remote learning in higher education during COVID-19 using machine learning techniques, PLoS ONE, 16(4): e0249423. [Online], [Retrieved July 7, 2021],https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0249423

- Holsapple, C. W., & Lee-Post, A. (2006), ‘Defining, assessing, and promoting e-learning success: An information systems perspective’, Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education, 4, 67–85.

- Juszczyk S. (2002), Edukacja na odleglosc. Kodyfikacja pojec, regul i procesow, Wydawnictwo Adam Marszalek, Torun.

- Kotler P., Keller K. L., (2011), Marketing Management, Fourteenth Edition, Pearson Education, Inc. ISBN 0132102927.

- Kuh, G. (2003), ‘What we’re learning about student engagement from NSSE’, Change, 35, 24–31.

- Kuo, Y.-C., Walker, A. E., Schroder, K. E., & Belland, B. R. (2013), ‘Interaction, internet self-efficacy, and self-regulated learning as predictors of student satisfaction in online education courses’, Internet and Education, 20, 35-50.

- Lee, H-J., Rha, I. (2009), ‘Influence of structure and interaction on student achievement and satisfaction in Web-based distance learning’, Educational Technology & Society, 12(4), 372-382.

- Liu L., Haque, M. D., (2017), ‘Age Difference in Research Course Satisfaction in a Blended Ed.D. Program: A Moderated Mediation Model of the Effects of Internet Self-Efficacy and Statistics Anxiety’, Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, v20 n2. [Online], [Retrieved July 7, 2021], https://www.westga.edu/~distance/ojdla/summer202/liu_haque202.html

- Longo Y., Gunz, Curtis G. J., FarsidesT., (2016), ‘Measuring Need Satisfaction and Frustration in Educational and Work Contexts: The Need Satisfaction and Frustration Scale’, Journal of Happiness Studies 17(1), 295-317.

- Martin F., Bolliger D. U., (2018), ‘Engagement matters: Student perceptions on the importance of engagement strategies in the online learning environment’, Online Learning, 22(1), 205- 222.

- Mohammad H., Hassan P.F., Khalijah Y.S. (2019), Quantitative Significance Analysis for Technical Competency of Malaysian Construction Managers, Issues in Built Environment, Universiti Tun Hussein Onn Malaysia 77-107. [Online], [Retrieved July 7, 2021], https://www.researchgate.net/publication/330184723

- Muzammil M, SutawıjayaA, Harsas (2020), ‘Investigating student satisfaction in online learning: the role of student interaction and engagement in distance learning University’, Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, (V:21); 88–96. [Online], [Retrieved July 7, 2021], https://doi.org/10.17718/tojde.770928

- Nandi, D., Hamilton, M., & Harland, J. (2012), ‘Evaluating the quality of interaction in asynchronous discussion forums in fully online courses’, Distance Education, 33, 5–30.

- Nguyen H. T., Pham H. T., Pham L., Limbu Y. B., Bui T. K. (2019), ‘Does e-learning service quality influence e-learning student satisfaction and loyalty? Evidence from Vietnam’, International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education; 16(7). [Online], [Retrieved July 30, 2021], https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-019-0136-3

- Owston, R., York, D., & Murtha, S. (2013), Student perceptions and achievement in a university blended learning strategic initiative, Internet and Higher Education, 18, 38-46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2012.12.003

- Palmer, S. R., Holt, D. M. (2009). ‘Examining student satisfaction with wholly online learning’, Journal of computer assisted learning, 25(2), 101-113.

- Parahoo S. K., Santally I., RajabaleeY., Harvey L. (2016), ‘Designing a predictive model of student satisfaction in online learning’, Journal of marketing for higher education, VOL. 26, NO. 1, 1–19. [Online], [Retrieved July 7, 2021], http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08841241.2015.1083511

- Pena M. I. C., SeeshingYeung A. (2010), ‘Satisfaction with Online Learning: Does Students’ Computer Competence Matter?’, The International Journal of Technology, Knowledge and Society, 6(5), 97-108, ISSN 1832-3669.

- Pérez-Villalobos C. Ventura-Ventura J., Spormann-Romeri C., Melipillán R., Jara-Reyes C., Paredes-Villarroel X., Rojas-Pino M., Baquedano-Rodríguez M., Castillo-Rabanal I., Parra-Ponce P., Bastías-Vega N., Alvarado-Figueroa D., Matus-Betancourt O., (2021), Satisfaction with remote teaching during the first semester of the COVID-19 crisis: Psychometric properties of a scale for health students, PLoS One; 16(4): e0250739.

- Plebanska M. (2020), Cyfrowa edukacja – potencjal, procesy, modele, Edukacja w czasach pandemii wirusa COVID-19. Z dystansem o tym, co robimy obecnie jako nauczyciele, Pyzalski J. (ed), Warszawa, EduAkcja.

- Reisinger Walker E., Lang D. L., Alperin M., Vu M., Barry C. M., Gaydos L. M. (2021), ‘Comparing Student Learning, Satisfaction, and Experiences Between Hybrid and In-Person Course Modalities: A Comprehensive, Mixed-Methods Evaluation of Five Public Health Courses’. Pedagogy in Health Promotion, Vol. 7(1) 29–37.

- Sebastianelli R., Swift C., Tamimi N. (2015), ‘Factors Affecting Perceived Learning, Satisfaction, and Quality in the Online MBA: A Structural Equation ModellingApproach’, Journal of education for business, 90: 296–305.

- Selhorst A. L., Williams L., Bao M. (2017), ‘The Effect of Transparent Instructor Guidelines on Student Success and Satisfaction in Online Classrooms: Curriculum Design and Effective Online Learning’, The International Journal of Adult, Community and Professional Learning, Volume 24, Issue 2, ISSN: 2328-6318 (Print), ISSN: 2328-6296.

- Sharma K., Deo G., Timalsina Joshi A., Shrestha N., Neupane H.C. (2020), ‘Online Learning in the Face of COVID-19 Pandemic: Assessment of Students’ Satisfaction at Chitwan Medical College of Nepal’, Kathmandu University Medical Journal, VOL. 18, NO. 2, ISSUE 70 |COVID-19 SPECIAL ISSUE.

- Shea, P. J., Swan, K., Fredericksen, E. E., & Pickett, A. M. (2002), Student satisfaction and reported learning in the SUNY learning network, Elements of quality online education: Learning effectiveness, cost effectiveness, access, faculty satisfaction, student satisfaction, J. Bourne, J. C. Moore (ed), Needham, MA: Olin College-Sloan Consortium, 145–156.

- Sheldon, K. M., & Hilpert, J. C. (2012), ‘The balanced measure of psychological needs (BMPN) scale: An alternative domain general measure of need satisfaction’, Motivationand Emotion, 36(4), 439-451.

- Sher, A. (2009), ‘Assessing the relationship of student-instructor and student-student interaction to student learning and satisfaction in web basedonline learning environment’, Journal of Interactive Online Learning, 8, 102–120.

- Shim TE, Lee SY. (2020), ‘College students’ experience of emergency remote teaching due to COVID-19′, Child Youth Serv Rev.; 119:105578. [Online], [Retrieved July 30, 2021], https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105578 PMID: 33071405

- Sinclaire J. K., (2012), ‘Vark learning style and student satisfaction with traditional and online courses’,International Journal of Education Research, Volume 7, Number 1, 77-89.

- So, H. J., Brush, T. A. (2008), ‘Student perceptions of collaborative learning, social presence and satisfaction in a blended learning environment: Relationships and critical factors’, Computers & education, 51(1), 318-336.

- Strang, K. D. (2011), ‘Asynchronous knowledge sharing and conversation interaction impact on grade in an online business course’, Journal of Education for Business, 86, 223–233.

- Sun, P. C., Tsai, R. J., Finger, G., Chen, Y. Y., & Yeh, D. (2008), ‘What drives a successful e-Learning? An empirical investigation of the critical factors influencing learner satisfaction’, Computers & education, 50(4), 1183-1202.

- Tomczyk L. (2020), Czego mozemy nauczyc sie od tych, ktorzy prowadza zdalna edukacje od dawna?, Edukacja w czasach pandemii wirusa COVID-19. Z dystansem o tym, co robimy obecnie jako nauczyciele, Pyzalski J. (ed) Warszawa, EduAkcja.

- Van Wart M., Ya NiA., Ready D., Shayo C., Courts J. (2020), ‘Factors Leading to Online Learner Satisfaction’, Business Education Innovation Journal, 12 (1), 14-24.

- Wei H.-C., Chou C. (2020), ‘Online learning performance and satisfaction: do perceptions and readiness matter?’, Distance education, VOL. 41, NO. 1, 48–69, [Online], [Retrieved July 7, 2021], https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2020.1724768

- Yawson D. E., Yamoah F. A., (2020), Understanding satisfaction essentials of E-learning in higher education: A multi-generational cohort perspective. Heliyon. 6(11), e05519. [Online], [Retrieved July 7, 2021],https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05519 PMID: 33251368.

- Zhou J., Zhang Q. (2021), ‘A Survey Study on U.S. College Students’ Learning Experience in COVID-19′, Education Sciences, 11, 248, [Online], [Retrieved July 30, 2021], https://doi.org/10.3390/

Appendix 1. Table of correlations with satisfaction from distance learning

Appendix 2. Cronbach Alpha Index for Indices

Appendix 3. Information about the sample